Our Great Lakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN OVERVIEW of the GEOLOGY of the GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J

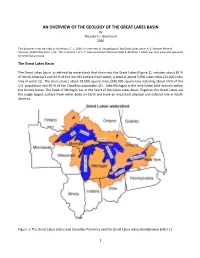

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES BASIN by Theodore J. Bornhorst 2016 This document may be cited as: Bornhorst, T. J., 2016, An overview of the geology of the Great Lakes basin: A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum, Web Publication 1, 8p. This is version 1 of A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum Web Publication 1 which was only internally reviewed for technical accuracy. The Great Lakes Basin The Great Lakes basin, as defined by watersheds that drain into the Great Lakes (Figure 1), includes about 85 % of North America’s and 20 % of the world’s surface fresh water, a total of about 5,500 cubic miles (23,000 cubic km) of water (1). The basin covers about 94,000 square miles (240,000 square km) including about 10 % of the U.S. population and 30 % of the Canadian population (1). Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States. The State of Michigan lies at the heart of the Great Lakes basin. Together the Great Lakes are the single largest surface fresh water body on Earth and have an important physical and cultural role in North America. Figure 1: The Great Lakes states and Canadian Provinces and the Great Lakes watershed (brown) (after 1). 1 Precambrian Bedrock Geology The bedrock geology of the Great Lakes basin can be subdivided into rocks of Precambrian and Phanerozoic (Figure 2). The Precambrian of the Great Lakes basin is the result of three major episodes with each followed by a long period of erosion (2, 3). Figure 2: Generalized Precambrian bedrock geologic map of the Great Lakes basin. -

The Laurentian Great Lakes

The Laurentian Great Lakes James T. Waples Margaret Squires Great Lakes WATER Institute Biology Department University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Brian Eadie James Cotner NOAA/GLERL Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior University of Minnesota J. Val Klump Great Lakes WATER Institute Galen McKinley University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Atmospheric and Oceanic Services University of Wisconsin-Madison Introduction forests. In the southern areas of the basin, the climate is much warmer. The soils are deeper with layers or North America’s inland ocean, the Great Lakes mixtures of clays, carbonates, silts, sands, gravels, and (Figure 7.1), contains about 23,000 km3 (5,500 cu. boulders deposited as glacial drift or as glacial lake and mi.) of water (enough to flood the continental United river sediments. The lands are usually fertile and have States to a depth of nearly 3 m), and covers a total been extensively drained for agriculture. The original area of 244,000 km2 (94,000 sq. mi.) with 16,000 deciduous forests have given way to agriculture and km of coastline. The Great Lakes comprise the largest sprawling urban development. This variability has system of fresh, surface water lakes on earth, containing strong impacts on the characteristics of each lake. The roughly 18% of the world supply of surface freshwater. lakes are known to have significant effects on air masses Reservoirs of dissolved carbon and rates of carbon as they move in prevailing directions, as exemplified cycling in the lakes are comparable to observations in by the ‘lake effect snow’ that falls heavily in winter on the marine coastal oceans (e.g., Biddanda et al. -

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Agreement: What Happens in the Great Lakes Won’T Stay in the Great Lakes

THE GREAT LAKES-ST. LAWRENCE RIVER BASIN AGREEMENT: WHAT HAPPENS IN THE GREAT LAKES WON’T STAY IN THE GREAT LAKES Kelly Kane This article provides a discussion of the current protections provided for the Great Lakes, and calls for an international binding agreement to ensure their continued protection. All past agreements between the United States and Canada to protect the Lakes have been purely good faith, and have no binding effect on the parties. The Great Lakes states and provinces have committed themselves to a good-faith agreement that bans all major withdrawals or diversions, subject to three exceptions. This Agreement has no legally binding effect on the states and provinces. The states, however, have created a legally binding Compact that does not include the Great Lakes provinces. The Great Lakes states have the power to make decisions regarding major withdrawals or diversions of Great Lakes water without the consent of the provinces. Although the current protections are morally binding, they will not provide enough protection for the Lakes given the increased concerns over water quality and quantity issues across the world. The federal governments of the United States and Canada should enter into a legally binding agreement to ensure the long-lasting enjoyment and protection of the Lakes. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 430 PART I: BACKGROUND ............................................................................... 432 A.Federalism and Water Management Approaches in the United States and Canada ........................................................................ 432 B.Legal History of Protections Placed on the Great Lakes ............. 433 C.Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement .................................................................. 438 D.The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact ...................................................................................... -

Rehabilitating Great Lakes Ecosystems

REHABILITATING GREAT LAKES ECOSYSTEMS edited by GEORGE R. FRANCIS Faculty of Environmental Studies University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 JOHN J. MAGNUSON Laboratory of Limnology University of Wisconsin-Madison Madison, Wisconsin 53706 HENRY A. REGIER Institute for Environmental Studies University of Toronto Toronto. Ontario M5S 1A4 and DANIEL R. TALHELM Department of Fish and Wildlife Michigan State University East Lansing, Michigan 48824 TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 37 Great Lakes Fishery Commission 1451 Green Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105 December 1979 CONTENTS Executive summary.. .......................................... 1 Preface and acknowledgements ................................. 2 1. Background and overview of study ........................... 6 Approach to the study. .................................... 10 Some basic terminology ................................... 12 Rehabilitation images ...................................... 15 2. Lake ecology, historical uses and consequences ............... 16 Early information sources. ................................. 17 Original condition ......................................... 18 Human induced changes in Great Lakes ecosystems ......... 21 Conclusion ............................................. ..3 0 3. Rehabilitation methods ...................................... 30 Fishing and other harvesting ............................... 31 Introductions and invasions of exotics ...................... 33 Microcontaminants: toxic wastes and biocides ............... 34 Nutrients and eutrophication -

US Geologic Survey

round goby<br /><br /> (Neogobius melanostomus) - FactSheet http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?SpeciesID=713 NAS - Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Home Alert System Database & Queries Taxa Information Neogobius melanostomus Collection Info (round goby) HUC Maps Fishes Point Maps Exotic to United States Fact Sheet ©Dave Jude, Center for Great Lakes Aquatic Sciences Neogobius melanostomus (Pallas 1814) Common name: round goby Synonyms and Other Names: Apollonia melanostoma (Pallas, 1814), Apollonia melanostomus (Pallas, 1814) See Stepien and Tumeo (2006) for name change. Taxonomy: available through Identification: Distinguishing characteristics have been given by Berg (1949), Miller (1986), Crossman et al. (1992), Jude (1993), and Marsden and Jude (1995). Young round gobies are solid slate gray. Older fish are blotched with black and brown and have a greenish dorsal fin with a black spot. The raised eyes on these fish are also very distinctive (Jude 1993). This goby is very similar to native sculpins but can be distinguished by the fused pelvic fins (sculpins have two separate fins) (Marsden and Jude 1995). Size: 30.5 cm; 17.8 cm maximum seen in United States (Jude 1993). Native Range: Fresh water, prefers brackish (Stepien and Tumeo 2006). Eurasia including Black Sea, Caspian Sea, and Sea of Azov and tributaries (Miller 1986). 1 of 6 7/21/2011 2:11 PM round goby<br /><br /> (Neogobius melanostomus) - FactSheet http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?SpeciesID=713 Alaska Hawaii Caribbean Guam Saipan Interactive maps: Point Distribution Maps Nonindigenous Occurrences: DETAILED DISTRIBUTION MAP This species was introduced into the St. Clair River and vicinity on the Michigan-Ontario border where several collections were made in 1990 on both the U.S. -

Great Lakes Compact

Great Lakes Compact Great Lakes - St. Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement Great Lakes - St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact Summary: > The Great Lakes Agreement and Compact seek to manage the Great Lakes watershed through a collaboration with all the states and provinces in the watershed. > Each state and province must pass a law to enact the Agreement or Compact, and that law will control diversions of water from the Great Lakes watershed. > The Sustainable Water Resources Agreement is an agreement among the Great Lakes States, Ontario and Québec. In Ontario it has been enacted into law through the Safeguarding and Sustaining Ontario’s Water Act of 2007 and legislation has been approved by the National Assembly in Québec. The states are in the process of implementing the Agreement through the Water Resources Compact. Created the Great Lakes - St. Lawrence River Water Resources Regional Body that includes the Great Lakes Governors and the Premiers of Ontario and Québec. > The Water Resources Compact is an agreement among the Great Lakes States that is passed into law through an interstate compact. The Compact has been enacted into law in all 8 Great Lakes states. Created the Council of Great Lakes Governors composed of Governors from each Great Lakes State or their designees. History of Interstate and International Cooperation: Boundary Waters Treaty - 1909: Purpose - to prevent disputes regarding the use of boundary waters and to ensure the equitable sharing of boundary waters between Canada and the US. Treaty created the International Joint Commission (IJC) to decide issues of water diversion in the Great Lakes, and placed Canada and the US at the forefront of international efforts to protect and manage natural resources. -

2019 State of the Great Lakes Report Michigan

MICHIGAN State of the Great Lakes 2019 REPORT 2019 STATE OF THE GREAT LAKES REPORT Page 1 Contents Governor Whitmer’s Message: Collaboration is Key ............................................................... 3 EGLE Director Clark’s Message: New Advocates for the Great Lakes Community ................. 4 New Standards Ensure Safe Drinking Water in the 21st Century ............................................ 5 Public Trust Doctrine and Water Withdrawals Aim to Protect the Great Lakes ........................ 8 High Water Levels Put State on Alert to Help Property Owners and Municipalities .................11 Asian Carp Threat from Chicago Area Looms Over Health of Lakes and Aquatic Life ............ 13 EGLE Collaborates on Research into Harmful Algal Blooms and Response Measures .......... 15 Initiatives Foster Stewardship, Raise Water Literacy for All Ages.......................................... 18 Michigan Communities Empowered to Take Action for Great Lakes Protection ...................... 22 EGLE Strengthens Michigan’s Sister State Relationship With Japan’s Shiga Prefecture ....... 24 Soo Locks Project Finally Underway with 2027 Target Date for Opening............................... 25 Great Lakes Cruises Make Bigger Waves in State’s Travel Industry ............................................. 26 MICHIGAN.GOV/EGLE | 800-662-9278 Prepared by the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy on behalf of the Office of the Governor (July 2020) 2019 STATE OF THE GREAT LAKES REPORT Page 2 Collaboration is Key hroughout the Great Lakes region, the health of our communities and the strength of our T economies depend on protecting our shared waters. The Great Lakes region encompasses 84 percent of the country’s fresh surface water, represents a thriving, $6 trillion regional economy supporting more than 51 million jobs, and supplies the drinking water for more than 48 million people. -

Fishes and Decapod Crustaceans of the Great Lakes Basin

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267883780 Ichthyofauna of the Great Lakes Basin Conference Paper · September 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 26 5 authors, including: Brian M. Roth Nicholas Mandrak Michigan State University University of Toronto 33 PUBLICATIONS 389 CITATIONS 173 PUBLICATIONS 2,427 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Greg G Sass Thomas Hrabik Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources University of Minnesota Duluth 95 PUBLICATIONS 796 CITATIONS 68 PUBLICATIONS 1,510 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Ecological Grass Carp Risk Assessment for the Great Lakes Basin View project All content following this page was uploaded by Greg G Sass on 14 September 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Fishes and Decapod Crustaceans of the Great Lakes Basin Brian M. Roth, Nicholas E. Mandrak, Th omas R. Hrabik, Greg G. Sass, and Jody Peters The primary goal of the first edition of this chapter (Coon 1994) was to provide an overview of the Laurentian Great Lakes fish community and its origins. For this edition, we have taken a slightly diff erent approach. Although we have updated the checklist of fishes in each of the Great Lakes and their watersheds, we also include a checklist of decapod crustaceans. Our decision to include decapods derives from the lack of such a list for the Great Lakes in the literature and the importance of decapods (in particular, crayfishes) for the ecology and biodiversity of streams and lakes in the Great Lakes region (Lodge et al. -

Lake Erie Watershed (Great Lakes Basin) Facts

Lake Erie Watershed (Great Lakes Basin) Facts Drainage Area: Total: 30,140 square miles (78,063 square kilometers) In Pennsylvania: 511 square miles (1,323 square kilometers) of land and 750 square miles of lake Size of Lake Erie: Length: 241 miles east to west Width: 57 miles north to south Depth: 62 feet average and 210 feet at maximum Surface Area of the Water: 9,910 square miles th Volume: 119 cubic miles (4 largest of the Great Lakes) Watershed Address from Headwaters to Mouth: The inflow of water comes via the Detroit River from Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, and many tributaries. The outflow of water is through the Niagara River and the Welland Canal. Major Tributaries in Pennsylvania: Conneaut Creek, Crooked Creek, Elk Creek, Mill Creek, Six Mile Creek, Sixteen Mile Creek, and Walnut Creek Population: Total: over 11 million people (10 million in the U.S. and 1.6 million in Canada) In Pennsylvania: more than 240,000 people Major Cities in Pennsylvania: Erie Who Is Responsible for the Overall Management of the Water Basin? Great Lakes Commission International Joint Commission – this Commission regulates flows on the St. Marys and St. Lawrence Rivers Economic Importance and Uses: Shipping, commercial and sport fishing, recreation, and drinking water Industrial Uses (2% of water usage): Manufacturing within PA includes plastics products, boilers, engines, turbines, castings, forgings, pipe equipment, motors, meters, tools, locomotives, and plastics. The fourth largest fossil-fueled electrical generating plant in North America is located on Lake Erie at Monroe, Michigan. -

Groundwater in the Great Lakes Basin

A Report of the Great Lakes Science Advisory Board to the International Joint Commission February 2010 GROUNDWATER IN THE GREAT LAKES BASIN INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION JOINT MIXTE COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE Canada and United States Canada et États-Unis Groundwater in the Great Lakes Basin A Report to the International Joint Commission from the IJC Great Lakes Science Advisory Board February 2010 The views expressed in this report are those of the individuals and organizations who participated in its compilation. They are not the views of the International Joint Commission. i Citation: Great Lakes Science Advisory Board to the International Joint Commission (IJC), 2010. Groundwater in the Great Lakes Basin, 2010. IJC, Windsor, Ontario, Canada. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within the report or its appendices. ISBN 1-894280-97-0 International Joint Commission Great Lakes Regional Office 100 Ouellette Ave., 8th Floor Windsor, Ontario N9A 6T3 Canada Telephone: (519) 257-6700, (313) 226-2170 World Wide Web: http://www.ijc.org This report is available in English in pdf format at: http://www.ijc.org/en/reports/2010/groundwater-in- the-great-lakes-basin This report, minus the Appendices, is available in French in pdf format at: http://www.ijc.org/fr/ reports/2010/groundwater-in-the-great-lakes-basin ii Contents Commissioners’ Preface v Groundwater in the Great Lakes Basin 1 Letter of Transmittal 8 Acknowledgements, Activities and Meetings, and Membership 10 Appendices 12 Appendix A Progress on Understanding Groundwater Issues in the Great Lakes Basin 13 Appendix B Threats to Groundwater Quality in the Great Lakes Basin — Pathogens 22 Appendix C Threats to Groundwater Quality in the Great Lakes -St. -

Program Book" Re- Flection Conveys a Message That Our Actions in the Basin Are Likely to Be Reflected in the Great Lakes

53rd Annual Conference on Great Lakes Research MAY 17 – 21 TORONTO International Association for Great Lakes Research Conference Theme Lessons from the past, Solution for the future The 53rd International Association for Great Lakes Research conference will explore how far re- search science in the Great Lakes and large lakes around the world has come over the decades, highlighting the science and policy research that has helped to improve and protect some as- pects of the Great Lakes. Today’s challenges and tomorrow’s solutions are rooted in this history as many of yesterday’s problems continue or have resurfaced today. Science and policy research presented in the areas of ecology, limnology, habitat, fisheries, invasive species, contaminants, climate impacts, watershed interactions, water quality and quantity will become part of the solu- tions for the future! Conference Logo The IAGLR-2010 logo symbolizes the conference theme. The pale blue coloured wave in the background represents the problem-plagued Great Lakes of the past, while the bright sky blue coloured wave in the foreground mimics the prosperous, rejuvenated Great Lakes aimed for in future. The CN Tower drawing highlights the conference venue—Toronto, Canada. Front Cover Design 53rd Annual Conference on Great Lakes Research The front cover of the program and abstract books illustrate the con- ference theme: Lessons from the past, Solutions for the future. The left vertical panel consisting of four pictures represents (mostly) historical or continuing issues for the Great Lakes such as point source pollution from industrial activities, nutrient & algae problems in Lake Erie, and the invasion of sea lamprey and mussels. -

Making Great Lakes Connections

OBJECTIVES After participating in this activity, learners will be able to: • identify the Great Lakes and the bodies of water that connect specific Great Lakes with each other and with the Atlantic Ocean • describe the three-dimensional geography of the Great Lakes, including elevations • describe why locks are needed, and how a lock system works ACTIVITY SUMMARY and a ship needs to be raised. Groups of learners work on a single Until the early 1800s, transportation Great Lake and connecting waterway and between the lakes and ocean was very then come together as a class to construct difficult. In 1825, the Erie Canal opened, a simple three-dimensional model of more directly connecting Lakes Ontario the Great Lakes. Individual groups also and Erie with the Atlantic Ocean via the present their Great Lake and connecting Hudson River and port of New York. waterway information. In 1829, the Welland Ship Canal was constructed between Lakes Ontario and Erie to provide a shipping channel around BACKGROUND Niagara Falls. (This canal was improved and enlarged several times from 1833 to The surface of Lake Superior is about 1919.) In 1855, the St. Mary’s Falls Ship 600 feet (184 meters) above sea level. To Canal (popularly known as the Soo Locks) allow ships to go from the Atlantic Ocean connecting Lake Superior and Lake (0 feet elevation) to the Great Lakes and back for international trade, the United DIAGRAM 1 States and Canada have constructed a series of locks, channels, and canals that raise and lower ships to the level of the lakes, rivers, and ocean (Diagram 1).