Perturbed Motion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astrodynamics

Politecnico di Torino SEEDS SpacE Exploration and Development Systems Astrodynamics II Edition 2006 - 07 - Ver. 2.0.1 Author: Guido Colasurdo Dipartimento di Energetica Teacher: Giulio Avanzini Dipartimento di Ingegneria Aeronautica e Spaziale e-mail: [email protected] Contents 1 Two–Body Orbital Mechanics 1 1.1 BirthofAstrodynamics: Kepler’sLaws. ......... 1 1.2 Newton’sLawsofMotion ............................ ... 2 1.3 Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation . ......... 3 1.4 The n–BodyProblem ................................. 4 1.5 Equation of Motion in the Two-Body Problem . ....... 5 1.6 PotentialEnergy ................................. ... 6 1.7 ConstantsoftheMotion . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... 7 1.8 TrajectoryEquation .............................. .... 8 1.9 ConicSections ................................... 8 1.10 Relating Energy and Semi-major Axis . ........ 9 2 Two-Dimensional Analysis of Motion 11 2.1 ReferenceFrames................................. 11 2.2 Velocity and acceleration components . ......... 12 2.3 First-Order Scalar Equations of Motion . ......... 12 2.4 PerifocalReferenceFrame . ...... 13 2.5 FlightPathAngle ................................. 14 2.6 EllipticalOrbits................................ ..... 15 2.6.1 Geometry of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 15 2.6.2 Period of an Elliptical Orbit . ..... 16 2.7 Time–of–Flight on the Elliptical Orbit . .......... 16 2.8 Extensiontohyperbolaandparabola. ........ 18 2.9 Circular and Escape Velocity, Hyperbolic Excess Speed . .............. 18 2.10 CosmicVelocities -

View and Print This Publication

@ SOUTHWEST FOREST SERVICE Forest and R U. S.DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE P.0. BOX 245, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94701 Experime Computation of times of sunrise, sunset, and twilight in or near mountainous terrain Bill 6. Ryan Times of sunrise and sunset at specific mountain- ous locations often are important influences on for- estry operations. The change of heating of slopes and terrain at sunrise and sunset affects temperature, air density, and wind. The times of the changes in heat- ing are related to the times of reversal of slope and valley flows, surfacing of strong winds aloft, and the USDA Forest Service penetration inland of the sea breeze. The times when Research NO& PSW- 322 these meteorological reactions occur must be known 1977 if we are to predict fire behavior, smolce dispersion and trajectory, fallout patterns of airborne seeding and spraying, and prescribed burn results. ICnowledge of times of different levels of illumination, such as the beginning and ending of twilight, is necessary for scheduling operations or recreational endeavors that require natural light. The times of sunrise, sunset, and twilight at any particular location depend on such factors as latitude, longitude, time of year, elevation, and heights of the surrounding terrain. Use of the tables (such as The 1 Air Almanac1) to determine times is inconvenient Ryan, Bill C. because each table is applicable to only one location. 1977. Computation of times of sunrise, sunset, and hvilight in or near mountainous tersain. USDA Different tables are needed for each location and Forest Serv. Res. Note PSW-322, 4 p. Pacific corrections must then be made to the tables to ac- Southwest Forest and Range Exp. -

Flight and Orbital Mechanics

Flight and Orbital Mechanics Lecture slides Challenge the future 1 Flight and Orbital Mechanics AE2-104, lecture hours 21-24: Interplanetary flight Ron Noomen October 25, 2012 AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 1 | Example: Galileo VEEGA trajectory Questions: • what is the purpose of this mission? • what propulsion technique(s) are used? • why this Venus- Earth-Earth sequence? • …. [NASA, 2010] AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 2 | Overview • Solar System • Hohmann transfer orbits • Synodic period • Launch, arrival dates • Fast transfer orbits • Round trip travel times • Gravity Assists AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 3 | Learning goals The student should be able to: • describe and explain the concept of an interplanetary transfer, including that of patched conics; • compute the main parameters of a Hohmann transfer between arbitrary planets (including the required ΔV); • compute the main parameters of a fast transfer between arbitrary planets (including the required ΔV); • derive the equation for the synodic period of an arbitrary pair of planets, and compute its numerical value; • derive the equations for launch and arrival epochs, for a Hohmann transfer between arbitrary planets; • derive the equations for the length of the main mission phases of a round trip mission, using Hohmann transfers; and • describe the mechanics of a Gravity Assist, and compute the changes in velocity and energy. Lecture material: • these slides (incl. footnotes) AE2104 Flight and Orbital Mechanics 4 | Introduction The Solar System (not to scale): [Aerospace -

Geodetic Position Computations

GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E. J. KRAKIWSKY D. B. THOMSON February 1974 TECHNICALLECTURE NOTES REPORT NO.NO. 21739 PREFACE In order to make our extensive series of lecture notes more readily available, we have scanned the old master copies and produced electronic versions in Portable Document Format. The quality of the images varies depending on the quality of the originals. The images have not been converted to searchable text. GEODETIC POSITION COMPUTATIONS E.J. Krakiwsky D.B. Thomson Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering University of New Brunswick P.O. Box 4400 Fredericton. N .B. Canada E3B5A3 February 197 4 Latest Reprinting December 1995 PREFACE The purpose of these notes is to give the theory and use of some methods of computing the geodetic positions of points on a reference ellipsoid and on the terrain. Justification for the first three sections o{ these lecture notes, which are concerned with the classical problem of "cCDputation of geodetic positions on the surface of an ellipsoid" is not easy to come by. It can onl.y be stated that the attempt has been to produce a self contained package , cont8.i.ning the complete development of same representative methods that exist in the literature. The last section is an introduction to three dimensional computation methods , and is offered as an alternative to the classical approach. Several problems, and their respective solutions, are presented. The approach t~en herein is to perform complete derivations, thus stqing awrq f'rcm the practice of giving a list of for11111lae to use in the solution of' a problem. -

Celestial Coordinate Systems

Celestial Coordinate Systems Craig Lage Department of Physics, New York University, [email protected] January 6, 2014 1 Introduction This document reviews briefly some of the key ideas that you will need to understand in order to identify and locate objects in the sky. It is intended to serve as a reference document. 2 Angular Basics When we view objects in the sky, distance is difficult to determine, and generally we can only indicate their direction. For this reason, angles are critical in astronomy, and we use angular measures to locate objects and define the distance between objects. Angles are measured in a number of different ways in astronomy, and you need to become familiar with the different notations and comfortable converting between them. A basic angle is shown in Figure 1. θ Figure 1: A basic angle, θ. We review some angle basics. We normally use two primary measures of angles, degrees and radians. In astronomy, we also sometimes use time as a measure of angles, as we will discuss later. A radian is a dimensionless measure equal to the length of the circular arc enclosed by the angle divided by the radius of the circle. A full circle is thus equal to 2π radians. A degree is an arbitrary measure, where a full circle is defined to be equal to 360◦. When using degrees, we also have two different conventions, to divide one degree into decimal degrees, or alternatively to divide it into 60 minutes, each of which is divided into 60 seconds. These are also referred to as minutes of arc or seconds of arc so as not to confuse them with minutes of time and seconds of time. -

New Closed-Form Solutions for Optimal Impulsive Control of Spacecraft Relative Motion

New Closed-Form Solutions for Optimal Impulsive Control of Spacecraft Relative Motion Michelle Chernick∗ and Simone D'Amicoy Aeronautics and Astronautics, Stanford University, Stanford, California, 94305, USA This paper addresses the fuel-optimal guidance and control of the relative motion for formation-flying and rendezvous using impulsive maneuvers. To meet the requirements of future multi-satellite missions, closed-form solutions of the inverse relative dynamics are sought in arbitrary orbits. Time constraints dictated by mission operations and relevant perturbations acting on the formation are taken into account by splitting the optimal recon- figuration in a guidance (long-term) and control (short-term) layer. Both problems are cast in relative orbit element space which allows the simple inclusion of secular and long-periodic perturbations through a state transition matrix and the translation of the fuel-optimal optimization into a minimum-length path-planning problem. Due to the proper choice of state variables, both guidance and control problems can be solved (semi-)analytically leading to optimal, predictable maneuvering schemes for simple on-board implementation. Besides generalizing previous work, this paper finds four new in-plane and out-of-plane (semi-)analytical solutions to the optimal control problem in the cases of unperturbed ec- centric and perturbed near-circular orbits. A general delta-v lower bound is formulated which provides insight into the optimality of the control solutions, and a strong analogy between elliptic Hohmann transfers and formation-flying control is established. Finally, the functionality, performance, and benefits of the new impulsive maneuvering schemes are rigorously assessed through numerical integration of the equations of motion and a systematic comparison with primer vector optimal control. -

Notes on Azimuth Reckoned from the South* a Hasty Examination of .The Early Rec.Orda of the Coast Survey, Hassler's Work 1N 1817

• \ , Notes on Azimuth reckoned from the South* A hasty examination of .the early rec.orda of the Coast Survey, Hassler's work 1n 1817 and work from 1830 on, suggests that there was no great uniformity of practice 1n the reckoning of azimuth. In working up astronomical observations it was sometimes reckoned from the north, apparently 1n either direction, without specially mentioning whether east or west, that point being determined by the attendant circumstances. However, 1n computing geodetic positions a form was used not unlike our present logarithmic form for the com putation of geodetic positions. This form was at first made out by hand but afterwards printed. In this form azimuth was counted from south through west up to 360°. A group of exceptions was noted, apparently a mere oversight. All this refers to the period around 1840. The formulas on which the form for position computa tion was based apparently came from Puissant. The proofs given in the earlier editions of Special Publication No. 8 , " resemble those in Puissant's Tra1te de Geodesle. The Library has the second edition dated 1819. Another source ( poggendorff) gives the date of the first edition as 1805. *See also 2nd paragraph on p. 94 of Special Pub. 8 2. ,The following passages are notes on or free translations from the second edit1on: Puissant Vol. I, p. 297 The formulas for position computation IIBlt 1 t 1s agreed in practice to reckon azimuths and longitudes from south to west and from zero to 400 grades" (360°). Puissant Vol. 1. p. 305 The formulas for position computation "The method just set forth for determining the geographic positions of the vertices of oblique triangles was proposed as early as 1787 by Legendre in a memoir on geodetic operations published by the Royal Academy of Sciences and 1s the one chiefly used by Delambre in the rec�nt measurement of a meridional arc. -

Mercury's Resonant Rotation from Secular Orbital Elements

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institute of Transport Research:Publications Mercury’s resonant rotation from secular orbital elements Alexander Stark a, Jürgen Oberst a,b, Hauke Hussmann a a German Aerospace Center, Institute of Planetary Research, D-12489 Berlin, Germany b Moscow State University for Geodesy and Cartography, RU-105064 Moscow, Russia The final publication is available at Springer via http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10569-015-9633-4. Abstract We used recently produced Solar System ephemerides, which incorpo- rate two years of ranging observations to the MESSENGER spacecraft, to extract the secular orbital elements for Mercury and associated uncer- tainties. As Mercury is in a stable 3:2 spin-orbit resonance these values constitute an important reference for the planet’s measured rotational pa- rameters, which in turn strongly bear on physical interpretation of Mer- cury’s interior structure. In particular, we derive a mean orbital period of (87.96934962 ± 0.00000037) days and (assuming a perfect resonance) a spin rate of (6.138506839 ± 0.000000028) ◦/day. The difference between this ro- tation rate and the currently adopted rotation rate (Archinal et al., 2011) corresponds to a longitudinal displacement of approx. 67 m per year at the equator. Moreover, we present a basic approach for the calculation of the orientation of the instantaneous Laplace and Cassini planes of Mercury. The analysis allows us to assess the uncertainties in physical parameters of the planet, when derived from observations of Mercury’s rotation. 1 1 Introduction Mercury’s orbit is not inertially stable but exposed to various perturbations which over long time scales lead to a chaotic motion (Laskar, 1989). -

SATELLITES ORBIT ELEMENTS : EPHEMERIS, Keplerian ELEMENTS, STATE VECTORS

www.myreaders.info www.myreaders.info Return to Website SATELLITES ORBIT ELEMENTS : EPHEMERIS, Keplerian ELEMENTS, STATE VECTORS RC Chakraborty (Retd), Former Director, DRDO, Delhi & Visiting Professor, JUET, Guna, www.myreaders.info, [email protected], www.myreaders.info/html/orbital_mechanics.html, Revised Dec. 16, 2015 (This is Sec. 5, pp 164 - 192, of Orbital Mechanics - Model & Simulation Software (OM-MSS), Sec 1 to 10, pp 1 - 402.) OM-MSS Page 164 OM-MSS Section - 5 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------43 www.myreaders.info SATELLITES ORBIT ELEMENTS : EPHEMERIS, Keplerian ELEMENTS, STATE VECTORS Satellite Ephemeris is Expressed either by 'Keplerian elements' or by 'State Vectors', that uniquely identify a specific orbit. A satellite is an object that moves around a larger object. Thousands of Satellites launched into orbit around Earth. First, look into the Preliminaries about 'Satellite Orbit', before moving to Satellite Ephemeris data and conversion utilities of the OM-MSS software. (a) Satellite : An artificial object, intentionally placed into orbit. Thousands of Satellites have been launched into orbit around Earth. A few Satellites called Space Probes have been placed into orbit around Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, etc. The Motion of a Satellite is a direct consequence of the Gravity of a body (earth), around which the satellite travels without any propulsion. The Moon is the Earth's only natural Satellite, moves around Earth in the same kind of orbit. (b) Earth Gravity and Satellite Motion : As satellite move around Earth, it is pulled in by the gravitational force (centripetal) of the Earth. Contrary to this pull, the rotating motion of satellite around Earth has an associated force (centrifugal) which pushes it away from the Earth. -

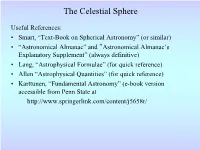

The Celestial Sphere

The Celestial Sphere Useful References: • Smart, “Text-Book on Spherical Astronomy” (or similar) • “Astronomical Almanac” and “Astronomical Almanac’s Explanatory Supplement” (always definitive) • Lang, “Astrophysical Formulae” (for quick reference) • Allen “Astrophysical Quantities” (for quick reference) • Karttunen, “Fundamental Astronomy” (e-book version accessible from Penn State at http://www.springerlink.com/content/j5658r/ Numbers to Keep in Mind • 4 π (180 / π)2 = 41,253 deg2 on the sky • ~ 23.5° = obliquity of the ecliptic • 17h 45m, -29° = coordinates of Galactic Center • 12h 51m, +27° = coordinates of North Galactic Pole • 18h, +66°33’ = coordinates of North Ecliptic Pole Spherical Astronomy Geocentrically speaking, the Earth sits inside a celestial sphere containing fixed stars. We are therefore driven towards equations based on spherical coordinates. Rules for Spherical Astronomy • The shortest distance between two points on a sphere is a great circle. • The length of a (great circle) arc is proportional to the angle created by the two radial vectors defining the points. • The great-circle arc length between two points on a sphere is given by cos a = (cos b cos c) + (sin b sin c cos A) where the small letters are angles, and the capital letters are the arcs. (This is the fundamental equation of spherical trigonometry.) • Two other spherical triangle relations which can be derived from the fundamental equation are sin A sinB = and sin a cos B = cos b sin c – sin b cos c cos A sina sinb € Proof of Fundamental Equation • O is -

2. Orbital Mechanics MAE 342 2016

2/12/20 Orbital Mechanics Space System Design, MAE 342, Princeton University Robert Stengel Conic section orbits Equations of motion Momentum and energy Kepler’s Equation Position and velocity in orbit Copyright 2016 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE342.html 1 1 Orbits 101 Satellites Escape and Capture (Comets, Meteorites) 2 2 1 2/12/20 Two-Body Orbits are Conic Sections 3 3 Classical Orbital Elements Dimension and Time a : Semi-major axis e : Eccentricity t p : Time of perigee passage Orientation Ω :Longitude of the Ascending/Descending Node i : Inclination of the Orbital Plane ω: Argument of Perigee 4 4 2 2/12/20 Orientation of an Elliptical Orbit First Point of Aries 5 5 Orbits 102 (2-Body Problem) • e.g., – Sun and Earth or – Earth and Moon or – Earth and Satellite • Circular orbit: radius and velocity are constant • Low Earth orbit: 17,000 mph = 24,000 ft/s = 7.3 km/s • Super-circular velocities – Earth to Moon: 24,550 mph = 36,000 ft/s = 11.1 km/s – Escape: 25,000 mph = 36,600 ft/s = 11.3 km/s • Near escape velocity, small changes have huge influence on apogee 6 6 3 2/12/20 Newton’s 2nd Law § Particle of fixed mass (also called a point mass) acted upon by a force changes velocity with § acceleration proportional to and in direction of force § Inertial reference frame § Ratio of force to acceleration is the mass of the particle: F = m a d dv(t) ⎣⎡mv(t)⎦⎤ = m = ma(t) = F ⎡ ⎤ dt dt vx (t) ⎡ f ⎤ ⎢ ⎥ x ⎡ ⎤ d ⎢ ⎥ fx f ⎢ ⎥ m ⎢ vy (t) ⎥ = ⎢ y ⎥ F = fy = force vector dt -

Orbital Mechanics

Orbital Mechanics Part 1 Orbital Forces Why a Sat. remains in orbit ? Bcs the centrifugal force caused by the Sat. rotation around earth is counter- balanced by the Earth's Pull. Kepler’s Laws The Satellite (Spacecraft) which orbits the earth follows the same laws that govern the motion of the planets around the sun. J. Kepler (1571-1630) was able to derive empirically three laws describing planetary motion I. Newton was able to derive Keplers laws from his own laws of mechanics [gravitation theory] Kepler’s 1st Law (Law of Orbits) The path followed by a Sat. (secondary body) orbiting around the primary body will be an ellipse. The center of mass (barycenter) of a two-body system is always centered on one of the foci (earth center). Kepler’s 1st Law (Law of Orbits) The eccentricity (abnormality) e: a 2 b2 e a b- semiminor axis , a- semimajor axis VIN: e=0 circular orbit 0<e<1 ellip. orbit Orbit Calculations Ellipse is the curve traced by a point moving in a plane such that the sum of its distances from the foci is constant. Kepler’s 2nd Law (Law of Areas) For equal time intervals, a Sat. will sweep out equal areas in its orbital plane, focused at the barycenter VIN: S1>S2 at t1=t2 V1>V2 Max(V) at Perigee & Min(V) at Apogee Kepler’s 3rd Law (Harmonic Law) The square of the periodic time of orbit is proportional to the cube of the mean distance between the two bodies. a 3 n 2 n- mean motion of Sat.