The Moray Food & Health Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Department Activity

NHS Scotland - Emergency Department Activity Attendances and Performance against the 4-hour Waiting Time Standard This is an ISD Scotland National Statistics release. The Scottish Government waiting time standard for emergency departments is that 98 % of all attendances should be seen within 4 hours. The figures presented in these tables detail the performance of each individual site and NHS board against the standard. Time Period: Apr-10 to Mar-11 Source: A&E data mart, ISD Scotland Date: 07 May 2012 List of Tables Table 1: Attendances and performance against 4-hour standard, Apr-10 to Mar-11 Total attendances, number of attendances breaching standard and attendances meeting standard (number and percentage). Figures are given at site and NHS Board level. Table 2: Attendances, Apr-10 to Mar-11 Summary table of attendances only. Figures are given at site and NHS Board level. Table 3: Performance against 4-hour standard, Apr-10 to Mar-11 Summary table of percentage of attendances meeting standard. Figures are given at site and NHS Board level. Notes: 1) The waiting time is defined as the time of arrival until the time of discharge, admission or transfer. 2) New presentations only; excludes planned return and recall attendances. 3) There are two types of site that provide emergency care; • ED - Emergency Departments; sites that provide a 24 hour emergency medicine consultant led service • MIU/Other - sites including minor injuries units (MIU), small hospitals and health centres in rural areas that carry out emergency department related activity and are GP or Nurse led. They may or may not be open 24 hours. -

Community Safety Partnership Report Issue 2022 September 2018

Community Safety Partnership Report Issue 2022 September 2018 Community Safety Community Safety is about protecting people’s rights to live in confidence without fear for their own or other people’s safety ensuring that people are safe from crime, disorder and danger and free from injury and harm and communities are socially cohesive and tolerant; are resilient and able to support individuals to take responsibility for their wellbeing The Community Safety Partnership aims to improve community safety across Moray by identifying and addressing immediate concerns in order to protect the most vulnerable and at risk and be proactive to ensure that communities feel safe. The CSP comprises of various Moray Council services, Police Scotland, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, NHS Grampian, tsiMORAY and Registered Social Landlords. WATER SAFETY With the continuing warm weather it is always tempting to go swimming to cool off. Water may look safe, but it can be dangerous. Learn to spot and keep away from dangers. You may swim well in a warm indoor pool, but that does not mean that you will be able to swim in cold water. The dangers of water include: • it is very cold • there may be hidden currents • it can be difficult to get out (steep slimy banks) • it can be deep • there may be hidden rubbish, e.g. shopping trolleys, broken glass • there are no lifeguards • it is difficult to estimate depth • it may be polluted and may make you ill Moray Local Command Area - Community Policing Inspectors Elgin Wards - Inspector Graeme Allan [email protected] -

SAUCHENBUSH ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY View SAUCHENBUSH, ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY, AB38 7AG

SAUCHENBUSH ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY View SAUCHENBUSH, ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY, AB38 7AG An impressive renovated farmhouse in a stunning elevated position Rothes 2 miles; Aberlour 6.5 miles; Elgin 10 miles. About 10.3 acres (4.17 ha). Ground Floor: Vestibule. Utility Room. Shower Room. Breakfasting Kitchen/Family Room. Hall. Sitting Room. Sun Room. Dining Room. Study. First Floor: Landing. 5 Bedrooms (2 En Suite). Family Bathroom. • Spacious family home • Some works outstanding • 6 superb stables and 1 tack room • Excellent paddock and former sand based riding arena • Stunning views over the surrounding countryside 5 Commerce Street Elgin Moray IV30 1BS 01343 546362 [email protected] to stay, eat and shop. The county is famed tow storeys. On the ground floor, the back for its breathtaking scenery, long sandy door opens into a spacious utility area beaches and wildlife and offers wonderful with a sink, wall and floor units, space leisure and recreational opportunities. for white goods and a shower room. A There are many golf courses accessible door leads to the kitchen/dining/family within a short drive including the room which is generous in size with attractive course in Rothes and as a plenty of work surface space and quality popular tourist area, local attractions fittings. The hall provides access to include ‘The Whisky Trail’, ‘The Speyside the wonderfully light triple aspect sun Way’ which passes nearby, Cairngorm room which enjoys stunning views over National Park, together with many ancient Strathspey and the Glen of Rothes. It also monuments, castles, buildings and has a door out to the garden. -

Contract Between Scottish Ministers

CONTRACT BETWEEN SCOTTISH MINISTERS AND GEOAMEY PECS LTD FOR THE SCOTTISH COURT CUSTODY AND PRISONER ESCORT SERVICE (SCCPES) REFERENCE: 01500 MARCH 2018 Official No part of this document may be disclosed orally or in writing, including by reproduction, to any third party without the prior written consent of SPS. This document, its associated appendices and any attachments remain the property of SPS and will be returned upon request. 1 | P a g e 01500 Scottish Court Custody and Prisoner Escort Service (SCCPES) FORM OF CONTRACT CONTRACT No. 01500 This Contract is entered in to between: The Scottish Ministers, referred to in the Scotland Act 1998, represented by the Scottish Prison Service at the: Scottish Prison Service Calton House 5 Redheughs Rigg Edinburgh EH12 9HW (hereinafter called the “Purchaser”) OF THE FIRST PART And GEOAmey PECS Ltd (07556404) The Sherard Building, Edmund Halley Road Oxford OX4 4DQ (hereinafter called the “Service Provider”) OF THE SECOND PART The Purchaser hereby appoints the Service Provider and the Service Provider hereby agrees to provide for the Purchaser, the Services (as hereinafter defined) on the Conditions of Contract set out in this Contract. The Purchaser agrees to pay to the Service Provider the relevant sums specified in Schedule C and due in terms of the Contract, in consideration of the due and proper performance by the Service Provider of its obligations under the Contract. The Service Provider agrees to look only to the Purchaser for the due performance of the Contract and the Purchaser will be entitled to enforce this Contract on behalf of the Scottish Ministers. -

Littlehaugh Cottage, Glen of Rothes, Aberlour, Moray

LITTLEHAUGH COTTAGE, GLEN OF ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY LITTLEHAUGH COTTAGE, GLEN OF ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY Two cottages built in the 1927 converted into one spacious home situated between Elgin and the village of Rothes. Description A96(T) road enabling Inverness and Aberdeen Airports General Information Littlehaugh Cottage is a charming 4 bedroom single to be reached within one and 1¼ hours respectively storey dwelling with slate roof. The property is traffic permitting. There are railway stations at Elgin, Services surrounded by a good sized garden and grounds of Aviemore (30 minutes), Inverness and Aberdeen. Mains water and electricity, private drainage and oil fired about 0.30 Ha (0.74 acres) and has good views to the central heating. east. It benefits from pvc double glazing and oil fired The Spey Valley is renowned for its excellent salmon central heating. fishing on the River Spey with the Rothes, Delfur and Rights of Way, Easements & Wayleaves Arndilly beats all within close proximity. The area also The access between the public road and the cottage is Situation abounds with golf courses and sandy beaches along included in the sale as shown on the plan. The small town of Rothes about 1½ miles to the the Moray coast. There are other opportunities for south provides basic daily requirements including two leisure activities such as mountaineering, skiing and Local Authority convenience stores, a butcher, chemist, library, post mountain biking in the nearby Cairngorm National Park. office, hotels and medical centre. Aberlour, about The Moray Council, Council Office 5 miles to the south has a supermarket, banks, a good Accommodation High Street, Elgin, Moray IV30 1BX range of shops, leisure facilities, doctor’s surgery and Littlehaugh Cottage is situated adjacent to the A941 Tel: 01343 543451 www.moray.gov.uk Speyside High School. -

Accident and Emergency: Performance Update

Accident and Emergency Performance update Prepared by Audit Scotland May 2014 Auditor General for Scotland The Auditor General’s role is to: • appoint auditors to Scotland’s central government and NHS bodies • examine how public bodies spend public money • help them to manage their finances to the highest standards • check whether they achieve value for money. The Auditor General is independent and reports to the Scottish Parliament on the performance of: • directorates of the Scottish Government • government agencies, eg the Scottish Prison Service, Historic Scotland • NHS bodies • further education colleges • Scottish Water • NDPBs and others, eg Scottish Police Authority, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service. You can find out more about the work of the Auditor General on our website: www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/about/ags Audit Scotland is a statutory body set up in April 2000 under the Public Finance and Accountability (Scotland) Act 2000. We help the Auditor General for Scotland and the Accounts Commission check that organisations spending public money use it properly, efficiently and effectively. Accident and Emergency | 3 Contents Summary 4 Key messages 7 Part 1. A&E waiting times 9 Part 2. Reasons for delays in A&E 20 Part 3. Action by the Scottish Government 37 Endnotes 41 Appendix 1. NHS Scotland A&E departments and minor injury units 43 Appendix 2. National context for A&E and unscheduled care, 2004 to 2014 45 Exhibit data When viewing this report online, you can access background data by clicking on the graph icon. The data file will -

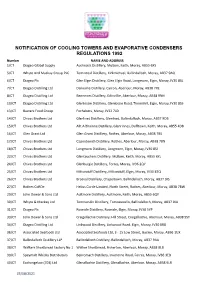

Cooling Tower Register

NOTIFICATION OF COOLING TOWERS AND EVAPORATIVE CONDENSERS REGULATIONS 1992 Number NAME AND ADDRESS 1/CTDiageo Global Supply Auchroisk Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6XS 5/CTWhyte And Mackay Group PLC Tomintoul Distillery, Kirkmichael, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9AQ 6/CTDiageo Plc Glen Elgin Distillery, Glen Elgin Road, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SL 7/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Dailuaine Distillery, Carron, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7RE 8/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Benrinnes Distillery, Edinvillie, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 9NN 10/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Glenlossie Distillery, Glenlossie Road, Thomshill, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SS 13/CTBaxters Food Group Fochabers, Moray, IV32 7LD 14/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenlivet Distillery, Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9DB 15/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Allt A Bhainne Distillery, Glenrinnes, Dufftown, Keith, Moray, AB55 4DB 16/CTGlen Grant Ltd Glen Grant Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BS 17/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Caperdonich Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BN 18/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Longmorn Distillery, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SJ 22/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glentauchers Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6YL 24/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenburgie Distillery, Forres, Moray, IV36 2QY 25/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Miltonduff Distillery, Miltonduff, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8TQ 26/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Braeval Distillery, Chapeltown, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9JS 27/CTRothes CoRDe Helius Corde Limited, North Street, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BW 29/CTJohn Dewar & Sons Ltd Aultmore Distillery, -

Of 5 Polling District Polling District Name Polling Place Polling Place Local Government Ward Scottish Parliamentary Cons

Polling Polling District Local Government Scottish Parliamentary Polling Place Polling Place District Name Ward Constituency Houldsworth Institute, MM0101 Dallas Houldsworth Institute 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Dallas, Forres, IV36 2SA Grant Community Centre, MM0102 Rothes Grant Community Centre 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray 46 - 48 New Street, Rothes, AB38 7BJ Boharm Village Hall, MM0103 Boharm Boharm Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Mulben, Keith, AB56 6YH Margach Hall, MM0104 Knockando Margach Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Knockando, Aberlour, AB38 7RX Archiestown Hall, MM0105 Archiestown Archiestown Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray The Square, Archiestown, AB38 7QX Craigellachie Village Hall, MM0106 Craigellachie Craigellachie Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray John Street, Craigellachie, AB38 9SW Drummuir Village Hall, MM0107 Drummuir Drummuir Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Drummuir, Keith, AB55 5JE Fleming Hall, MM0108 Aberlour Fleming Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Queens Road, Aberlour, AB38 9PR Mortlach Memorial Hall, MM0109 Dufftown & Cabrach Mortlach Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Albert Place, Dufftown, AB55 4AY Glenlivet Public Hall, MM0110 Glenlivet Glenlivet Public Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EJ Richmond Memorial Hall, MM0111 Tomintoul Richmond Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Tomnabat Lane, Tomintoul, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EZ McBoyle Hall, BM0201 Portknockie McBoyle Hall 2 - Keith and Cullen Banffshire and Buchan Coast Seafield -

The Findhorn, Nairn & Speyside Local Flood Risk Management Plan

Foreword The impacts of flooding experienced by individuals, communities and businesses can be devastating and long lasting. It is vital that we continue to reduce the risk of any such future events and improve Scotland’s ability to manage and recover from any events that occur. The publication of this Plan is an important milestone in implementing the Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009 and improving our understanding of flood risk and how we will manage floods in the Findhorn, Nairn and Speyside Local Plan District. The Plan translates this legislation into actions to reduce the damage and distress caused by flooding over the first planning cycle from 2016 to 2022 and beyond. Within the Local Plan District (LPD), areas with the greatest risk of flooding have been identified and these have been designated as Potentially Vulnerable Areas (PVAs). The actions identified in the Plan are within these PVAs. The current PVAs were designated using the best information available at the time and additional PVAs may be identified when investigation work is done during the development of future plans. In summary, there are fourteen areas that have been identified as being potentially vulnerable to flood risk across the Findhorn, Nairn and Speyside LPD. Across the entire district there are a total of 1,800 residential and 580 non-residential properties at risk of flooding with estimated Annual Average Damages of £5.9 million. The Findhorn, Nairn and Speyside Local Flood Risk Management Plan published by The Moray Council has been developed in partnership and with the agreement of: The Highland Council, Scottish Water; SEPA; Forestry Commission Scotland; and Cairngorms National Park Authority. -

Here Is the Brief for Thursday 13 May 2021. Moray Update Additional Mobile Testing Units Are to Be Deployed in Lossiemouth, Keit

can Here is the brief for Thursday 13 May 2021. Moray update Additional mobile testing units are to be deployed in Lossiemouth, Keith, and Aberlour as part of ongoing efforts to bring case numbers in Moray under control. There are currently no plans to progress to door-to-door testing anywhere in the area. Public Health believe we may now be seeing the outbreak in Elgin starting to plateau. Despite this, the figures in Moray are still well ahead of the rest of the country. We are starting to see signs of outbreaks in other communities outside of Elgin, including in Keith, Lossiemouth and Aberlour, hence why mobile testing will be deployed there. The number of tests undertaken in Moray has risen by 400% and there has been strong public support of the accelerated COVID-19 vaccination programme in the area. COVID-19 vaccination – community outreach As part of the accelerated roll-out of the COVID-19 vaccination programme in Moray, a community clinic took place today at Hythehill Primary School in Lossiemouth. The team will also be running a clinic at Keith Primary School tomorrow. This is in addition to extended opening hours at the Fiona Elcock Vaccination Centre in Elgin. Community clinics are also scheduled for Aberdeen City next week, at Tillydrone Hub (19/5), Gerrard St Baptist Church (20/5), and Seaton Community Church (21/5). Booking information for these clinics is going out directly in a targeted leaflet drop; these clinics are for anyone aged 40 and over who have not yet had their first dose of vaccine. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Mental Health Bed Census

Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Data Collection Documentation Document Type: Guidance Notes Collections: 1. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census: One Day Audit 2. Mental Health and Learning Disability Patients: Out of Scotland and Out of NHS Placements SG deadline: 30th November 2014 Coverage: Census date: Midnight, 29th Oct 2014 Page 1 – 10 Nov 2014 Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Document Details Issue History Version Status Authors Issue Date Issued To Comments / changes 1.0 Draft Moira Connolly, NHS Boards Beth Hamilton, Claire Gordon, Ellen Lynch 1.14 Draft Beth Hamilton, Ellen Lynch, John Mitchell, Moira Connolly, Claire Gordon, 2.0 Final Beth Hamilton, 19th Sept 2014 NHS Boards, Ellen Lynch, Scottish John Mitchell, Government Moira Connolly, website Claire Gordon, 2.1 Final Ellen Lynch 9th Oct 2014 NHS Boards, Further clarification included for the following data items:: Scottish Government Patient names (applicable for both censuses) website ProcXed.Net will convert to BLOCK CAPITALS, NHS Boards do not have to do this in advance. Other diagnosis (applicable for both censuses) If free text is being used then separate each health condition with a comma. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census o Data item: Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis on admission Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option. o Data item: Last known Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option.