Reasons Why Dravidian Boys in Australia Do Or Do Not Choose to Learn Bharatanatyam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

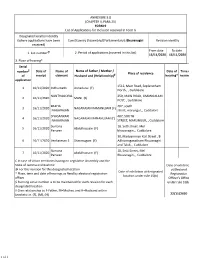

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons have been Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Bhuvanagiri Revision identy received) From date To date 1. List number @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial number $ Date of Name of Name of Father / Mother / Date of Time of Place of residence of receipt claimant Husband and (Relaonship) # hearing* hearing* applicaon 1512, Main Road, Seplanatham 1 16/11/2020 Indhumathi Annadurai (F) North , , Cuddalore NANTHAGOPAL 259, MAIN ROAD, UMANGALAM 2 16/11/2020 MANI (F) POST, , Cuddalore BAKIYA 407, south 3 16/11/2020 NAGARAJAN RAMANUJAM (F) NAGARAJAN street, marungur, , Cuddalore SIVASANKARI 407, SOUTH 4 16/11/2020 NAGARAJAN RANANUJAM (F) NAGARAJAN STREET, MARUNGUR, , Cuddalore Sumana 18, Se street, Mel 5 16/11/2020 Abdulhussain (F) Parveen bhuvanagiri, , Cuddalore 30, Mariyamman Koil Street , B 6 16/11/2020 Venkatesan S Shanmugam (F) Adhivaraganatham Bhuvanagiri and Taluk, , Cuddalore Sumana 18, Se Street, Mel 7 16/11/2020 Abdulhussain (F) Parveen Bhuvanagiri, , Cuddalore £ In case of Union territories having no Legislave Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir Date of exhibion @ For this revision for this designated locaon at Electoral Date of exhibion at designated * Place, me and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registraon Registraon locaon under rule 15(b) officer Officer’s Office $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each under rule 16(b) designated locaon # Give relaonship as F-Father, M=Mother, and H=Husband within brackets i.e. -

The Un/Selfish Leader Changing Notions in a Tamil Nadu Village

The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Björn Alm The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Doctoral dissertation Department of Social Anthropology Stockholm University S 106 91 Stockholm Sweden © Björn Alm, 2006 Department for Religion and Culture Linköping University S 581 83 Linköping Sweden This book, or parts thereof, may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. ISBN 91-7155-239-1 Printed by Edita Sverige AB, Stockholm, 2006 Contents Preface iv Note on transliteration and names v Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Structure of the study 4 Not a village study 9 South Indian studies 9 Strength and weakness 11 Doing fieldwork in Tamil Nadu 13 Chapter 2 The village of Ekkaraiyur 19 The Dindigul valley 19 Ekkaraiyur and its neighbours 21 A multi-linguistic scene 25 A religious landscape 28 Aspects of caste 33 Caste territories and panchayats 35 A village caste system? 36 To be a villager 43 Chapter 3 Remodelled local relationships 48 Tanisamy’s model of local change 49 Mirasdars and the great houses 50 The tenants’ revolt 54 Why Brahmans and Kallars? 60 New forms of tenancy 67 New forms of agricultural labour 72 Land and leadership 84 Chapter 4 New modes of leadership 91 The parliamentary system 93 The panchayat system 94 Party affiliation of local leaders 95 i CONTENTS Party politics in Ekkaraiyur 96 The paradox of party politics 101 Conceptualising the state 105 The development state 108 The development block 110 Panchayats and the development block 111 Janus-faced leaders? 119 -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Commencement Prayer an Invocation By: Alexander Levering Kern, Executive Director of the Center for Spirituality, Dialogue, and Service

ommencement C 9 MAY 2021 CONTENTS This program is for ceremonial purposes only and is not to be considered an official confirmation of degree information. It contains only those details available at the publication deadline. History of Northeastern University 2 Program 5 Featured Speakers 10 Degrees in Course 13 Doctoral Degrees Professional Doctorate Degrees Bouvé College of Health Sciences Master's Degrees College of Arts, Media and Design Khoury College of Computer Sciences College of Engineering Bouvé College of Health Sciences College of Science College of Social Sciences and Humanities School of Law Presidential Cabinet 96 Members of the Board of Trustees, Trustees Emeriti, Honorary Trustees, and Corporators Emeriti 96 University Marshals 99 Faculty 99 Color Guard 100 Program Notes 101 Alma Mater 102 1 A UNIVERSITY ENGAGED WITH THE WORLD THE HISTORY OF NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Northeastern University has used its leadership in experiential learning to create a vibrant new model of academic excellence. But like most great institutions of higher learning, Northeastern had modest origins. At the end of the nineteenth century, immigrants and first-generation Americans constituted more than half of Boston’s population. Chief among the city’s institutions committed to helping these people improve their lives was the Boston YMCA. The YMCA became a place where young men gathered to hear lectures on literature, history, music, and other subjects considered essential to intellectual growth. In response to the enthusiastic demand for these lectures, the directors of the YMCA organized the “Evening Institute for Young Men” in May 1896. Frank Palmer Speare, a well- known teacher and high-school principal with considerable experience in the public schools, was hired as the institute’s director. -

Page BRAHMANISM, BRAHMINS and BRAHMIN TAMIL in the CONTEXT of SPEECH to TEXT TECHNOLOGY Corresponding Email:[email protected]

BRAHMANISM, BRAHMINS AND BRAHMIN TAMIL IN THE CONTEXT OF SPEECH TO TEXT TECHNOLOGY R S Vignesh Raja, Ashik Alib Dr. BabakKhazaeic aResearch degree student, cSenior Lecturer Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, United Kingdom bSoftware Developer Fireflyapps Limited, Sheffield, United Kingdom Corresponding email:[email protected] Abstract Brahmanism in today's world is largely viewed as a 'caste' within Hinduism than its predecessor religion. This research paper explores the impact and influence religious affiliation could have on using certain advanced technologies such as the voice-to-text. This research paper attempts to reintroduce Brahmanism as a distinct religion and justifies through an empirical study and other literature as to why it is important, more specifically in language-related technology. Keywords: Tamil; speech to text; technology; Brahmanism; Brahmins 1. Introduction Speech-to-text is a fascinating area of research. The speech-to-text system exists for popular languages such as English. Whilst dealing with the user acceptance of technology, previous experiments suggest that it is vital to consider the religious affiliation as it could influence 'pronunciation' which is perceived to be very important for the users to be able to use voice-to- text technology in syllabic languages such as Tamil (Rama et al., 2002). Some of the previous experiments have identified the effect of code mixing, mispronunciation or in some cases the inability to correctly pronounce a syllable by the native Tamil speakers (Raj, Ali&Khazaei, 2015). This research paper aims to look into the code mixing and pronunciation aspects of 'Brahmin Tamil'- a dialect of Tamil spoken by the Brahmins who speak Tamil as their mother tongue. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Tamil Brahmin Wedding

TAMIL BRAHMIN WEDDING THE RITUALS AND THE RATIONALE The Hindu Wedding Ceremony has a number of rituals and customs most of which are often felt as superstitious or a waste of time. It is believed to be nothing but rituals and more rituals. But actually what is a " Ritual " ? A ritual begins as a creative rational action to express a sentiment or idea. – For example the lighting of a lamp to dispel darkness at twilight or folding of hands into a "Namaste" to greet an elder. As succeeding generations repeat the actions it becomes a convention – then a RITUAL. A ritual is thus an action on which time has set its seal of approval. The Ritual of the Hindu Wedding too is thus each symbolic of beautiful and noble sentiments. Unfortunately today many perform them without an awareness of the rich meaning behind them. A modest attempt has therefore been made to briefly describe the meaning and significance of the rituals of a Tamil Brahmin Wedding after going through many articles in Internet and compiled them. For the elders, this information may be superfluous but it is hoped that the younger generations, especially those yet to be married, may find this useful. So let me take you on a tour . PANDHAL KAAL MUHURTHAM A small ritual is performed a few days before or at least one day before the wedding to invoke the blessings of the family deity to ensure that the wedding preparations proceed smoothly. The family of the bride pray to the deity who is symbolically represented by a bamboo pole. -

Commencement Opening Ceremony

Commencement Opening Ceremony May 14, 2016 Chicago, Illinois Illinois Institute of Technology 2016 Commencement Opening Ceremony The Fourteenth of May Two Thousand and Sixteen Ten in the morning Ed Glancy Field 31st Street and Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois elcome to IIT’s 147th Commencement Exercise. The university community extends cordial greetings to the families and friends who are gathered W here to celebrate the culmination of years of formal study. For 2,668 students, today’s ceremony officially recognizes their academic accomplishments during the 2015–16 academic year and inaugurates a new era in their lives. With a broad foundation of both intellectual capability and experiential learning that characterizes an IIT education, these graduates also take with them a sound understanding of contemporary society and its values as they join thousands of other IIT alumni. About Illinois Institute of Technology In 1890, when advanced education was often reserved for society’s elite, Chicago minister Frank Wakely Gunsaulus delivered what came to be known as the “Million Dollar Sermon” near the site Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) now occupies. Gunsaulus said that with a million dollars he would build a school where students of all backgrounds could prepare for meaningful roles in a changing industrial society. Philip Danforth Armour, a Chicago meatpacking industrialist and grain merchant, heard the sermon and came to share the minister’s vision, agreeing to finance the endeavor with the stipulation that Gunsaulus become the first president of Armour Institute. When Armour Institute opened in 1893, it offered professional courses in engineering, chemistry, architecture, and library science. -

The Psbb Millennium School Gst & Gerugambakkam

THE PSBB MILLENNIUM SCHOOL GST & GERUGAMBAKKAM S.No Employee Name Level 1 Bhavani Baskar Principal 2 Rukmani D Kindergarten 3 Devi Krishnan Kindergarten 4 Harini Parthasarathy Kindergarten 5 K Logasundari Kindergarten 6 K S Sudhakar Kindergarten 7 S Vanitha Kindergarten 8 Umamaheswari S Kindergarten 9 Usha Manivannan Kindergarten 10 V Mahalakshmi Kindergarten 11 Vidhya Arunkumar Kindergarten 12 Priya B Primary 13 Perathu Selvi M P Primary 14 Durgalakshmi G Primary 15 Shalini Ragupathi Primary 16 Simey Rajesh Primary 17 Sree Latha Srinivasan Primary 18 W Sheela Primary 19 Geetha Primary 20 Priya Kannan Primary 21 Dheepti. A Primary 22 A Deepa Primary 23 N Rajashree Primary 24 Shree Lakshmi V Primary 25 R Kavithaa Primary 26 Jayalakshmi R Primary 27 P Devi Primary 28 Josephine Mary C Primary 29 T R R Sangeethamai Primary 30 Sathiyapriya Sanjeev Primary 31 Sujatha Subramanian Primary 32 Latha V Primary 33 Uma Magesh Primary 34 Sandhya Srinivas Primary 35 P Rengalakshmi Primary 36 J.Ramya Primary 37 Vidhya J Primary 38 A Seetha Devi Primary 39 Alred Starlin P V Primary 40 Angshumitra Banerjee Primary 41 Dhaya Sreenivasan Primary 42 Haritha Shree R Primary 43 Jeevalakshmi K Primary 44 M Latha Primary 45 Malini Subramanian Primary 46 P Arockia Punitha Primary 47 Rajeswari B Primary 48 Rathnakumari R Primary 49 Renubala Sahoo Primary 50 Saraswathi S Primary 51 Shanthy K Primary 52 Subha Iyer Primary 53 Sumitha K Primary 54 Sunitha R Primary 55 Deepa T K Primary 56 Suchithra Primary 57 Mohanambal. P Primary 58 Deepa seshadri Primary 59 Padmavathi -

Download The

Nicole A. Wilson Syracuse University Confrontation and Compromise Middle-Class Matchmaking in Twenty-First Century South India During my fifteen-month stay in the suburbs of Madurai, Tamilnadu, South India, I was privileged to witness the complicated process of marriage alli- ance matchmaking for several Tamil youth, including Radhika Narayanan, a twenty-one-year-old Tamil Brahmin girl and close friend, as well as another bride-to-be, Priya. Using conversations with Radhika, her family members, and her friends, as well as data extrapolated from participant observation in both Radhika’s and Priya’s matrimonial events, this article uses the multitudi- nous modes of matchmaking employed by both women’s families to investigate the complexity and delicate balance inherent in contemporary matchmaking among middle-class Tamils and India’s burgeoning middle classes. In high- lighting the confrontations between materialism and morality, neocolonial- ism and nationalism, and individualism and filial piety that lie at the heart of middle-class matchmaking, this ethnographic examination will provide insight into the world views and lifestyles belonging to and shaping one of the most powerful segments of our global community. keywords: middle class—matchmaking—south India—peṇ pārkka— modernity Asian Ethnology Volume 72, Number 1 • 2013, 33–53 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture adhika’s family and I had spent the entire previous day scrubbing the house R from top to bottom in order to prepare for our honored guests.* We had seen a picture of the possible groom’s home and were already feeling inadequate about the appearance of our home and its contents. -

Being Brahmin, Being Modern

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Being Brahmin, Being Modern Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 ii (Blank) Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Being Brahmin, Being Modern Exploring the Lives of Caste Today Ramesh Bairy T. S. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 First published 2010 by Routledge 912–915 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2010 © 2010 Ramesh Bairy T. S. Typeset by Bukprint India B-180A, Guru Nanak Pura, Laxmi Nagar Delhi 110 092 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-58576-7 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 For my parents, Smt. Lakshmi S. Bairi and Sri. T. Subbaraya Bairi. And, University of Hyderabad. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 vi (Blank) Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Contents Acknowledgements ix Chapter 1 Introduction: Seeking a Foothold -

Analysis of the Religious Practices of Hindus at Saint Joseph's Oratory

UNIVERSITÉ DE MONTRÉAL Analysis of the Religious Practices of Hindus at Saint Joseph’s Oratory Transmission of Christian Faith after the Second Vatican Council Par John Jomon Kalladanthiyil Faculté des arts et des sciences Institut d’études religieuses Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph. D. en Théologie pratique Mars 2017 © Jomon Kalladanthiyil, 2017 Résumé Dès le début du christianisme, la transmission de la foi chrétienne constitue la mission essentielle de l’Église. Dans un contexte pluri-religieux et multiculturel, le concile Vatican II a reconnu l’importance d’ouvrir la porte de l’Église à tous. Basile Moreau (1799 – 1873), le fondateur de la congrégation de Sainte-Croix, insistait sur le fait que les membres de sa communauté soient des éducateurs à la foi chrétienne et il a envoyé des missionnaires au Québec dès la fondation de sa communauté (1837). Pour ces derniers, parmi d’autres engagements pastoraux, l’Oratoire Saint-Joseph du Mont-Royal, fondé par Alfred Bessette, le frère André (1845 – 1937), est devenu l’endroit privilégié pour la transmission de la foi chrétienne, même après la Révolution tranquille des années 1960. L’Oratoire Saint-Joseph accueille des milliers d’immigrants du monde entier chaque année et parmi eux beaucoup d’hindous. Pour beaucoup d’entre eux, l’Oratoire devient un second foyer où ils passent du temps en prière et trouvent la paix. Certains d’entre eux ont l’expérience de la guérison et des miracles. Le partage de l’espace sacré avec les hindous est un phénomène nouveau à l’Oratoire.