EDDIE PALMIERI NEA Jazz Master (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Mambo on 2: the Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City

Centro Journal ISSN: 1538-6279 [email protected] The City University of New York Estados Unidos Hutchinson, Sydney Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City Centro Journal, vol. XVI, núm. 2, fall, 2004, pp. 108-137 The City University of New York New York, Estados Unidos Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=37716209 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 108 CENTRO Journal Volume7 xv1 Number 2 fall 2004 Mambo On 2: The Birth of a New Form of Dance in New York City SYDNEY HUTCHINSON ABSTRACT As Nuyorican musicians were laboring to develop the unique sounds of New York mambo and salsa, Nuyorican dancers were working just as hard to create a new form of dance. This dance, now known as “on 2” mambo, or salsa, for its relationship to the clave, is the first uniquely North American form of vernacular Latino dance on the East Coast. This paper traces the New York mambo’s develop- ment from its beginnings at the Palladium Ballroom through the salsa and hustle years and up to the present time. The current period is characterized by increasing growth, commercialization, codification, and a blending with other modern, urban dance genres such as hip-hop. [Key words: salsa, mambo, hustle, New York, Palladium, music, dance] [ 109 ] Hutchinson(v10).qxd 3/1/05 7:27 AM Page 110 While stepping on count one, two, or three may seem at first glance to be an unimportant detail, to New York dancers it makes a world of difference. -

Andy Gonzalez Entre Colegas Download Album Bassist Andy González, Who Brought Bounce to Latin Dance and Jazz, Dies at 69

andy gonzalez entre colegas download album Bassist Andy González, Who Brought Bounce To Latin Dance And Jazz, Dies At 69. Andy González, a New York bassist who both explored and bridged the worlds of Latin music and jazz, has died. The 69-year-old musician died in New York on Thursday night, from complications of a pre-existing illness, according to family members. Born and bred in the Bronx, Andy González epitomized the fiercely independent Nuyorican attitude through his music — with one foot in Puerto Rican tradition and the other in the cutting-edge jazz of his native New York. González's career stretched back decades, and included gigs or recordings with a who's-who of Latin dance music, including Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri and Ray Barretto. He also played with trumpeter and Afro-Cuban jazz pioneer Dizzy Gillespie while in his twenties, as he explored the rich history of Afro-Caribbean music through books and records. In the mid-1970s, he and his brother, the trumpet and conga player Jerry González, hosted jam sessions — in the basement of their parents' home in the Bronx — that explored the folkloric roots of the then-popular salsa movement. The result was an influential album, Concepts In Unity, recorded by the participants of those sessions, who called themselves Grupo Folklórico y Experimental Nuevayorquino. Toward the end of that decade, the González brothers were part of another fiery collective known as The Fort Apache Band, which performed sporadically and went on to release two acclaimed albums in the '80s — and continued to release music through the following decades — emphasizing the complex harmonies of jazz with Afro-Caribbean underpinnings. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Spinning Wheel (1969) Blood, Sweat & Tears

MUSC-21600: The Art of Rock Music Prof. Freeze Spinning Wheel (1969) Blood, Sweat & Tears LISTEN FOR • Fusion of musical styles • Prominent horn section (like in big band) • Sophisticated jazz harmonies, improvisation • Syncopated R&B bass riffs • Heavy rock backbeat CREATION Songwriters David Clayton-Thomas Album Blood, Sweat & Tears Label Columbia 44871 Musicians David Clayton-Thoma (vocals), Steve Katz (guitar), Bobby Colomby (drums), Jim Fielder (Bass), Fred Lipsius (alto saxophone), Lew Soloff (trumpet), Alan Rubin (trumpet), Jerry Hyman (trombone), Dick Halligan (piano) Producer James William Guercio Engineer Roy Halee, Fred Catero Recording October 1968; stereo Charts Pop 2, Easy 1, R&B 45 MUSIC Genre Jazz rock Form Simple verse with contrasting middle section, improvised solos, complex outro Key G major Meter 4/4 (alternates with 3/8 in Coda) MUSC-21600 Listening Guide Freeze “Spinning Wheel” (Blood, Sweat & Tears, 1969) LISTENING GUIDE Time Form Lyric Cue Listen For 0:00 Intro • Short intro for horns, with crescendo on sustained note and then riff punctuated by snare. 0:07 A1 “What goes up” • Vocals enter, accompanying texture gradually accumulates, starting with R&B bass/piano riff, then cowbell, drums, tambourine, horns. 0:21 • Refrain begins with stop time. 0:26 A2 “You got no money” • As before, with big-band-inspired horn section punctuating the texture, sometimes with jazzy, swung filler. 0:41 • Refrain. 0:46 B “Did you find” • Extensive contrasting section. • More four-square rhythmic structure with slower harmonic rhythm. • Ends with digital distortion of last vocal note. 1:16 Intro • Overlaps with previous section. 1:30 A3 “Someone is waiting” • As in A2, but with stop time for new stop time for trombone glissando (slide). -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

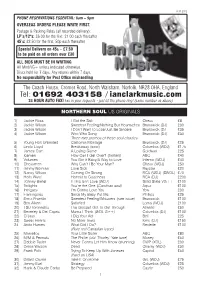

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition

Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition by William D. Scott Bachelor of Arts, Central Michigan University, 2011 Master of Music, University of Michigan, 2013 Master of Arts, University of Michigan, 2015 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by William D. Scott It was defended on March 28, 2019 and approved by Mark A. Clague, PhD, Department of Music James P. Cassaro, MA, Department of Music Aaron J. Johnson, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Michael C. Heller, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by William D. Scott 2019 iii Michael C. Heller, PhD Hybridity and Identity in the Pan-American Jazz Piano Tradition William D. Scott, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 The term Latin jazz has often been employed by record labels, critics, and musicians alike to denote idioms ranging from Afro-Cuban music, to Brazilian samba and bossa nova, and more broadly to Latin American fusions with jazz. While many of these genres have coexisted under the Latin jazz heading in one manifestation or another, Panamanian pianist Danilo Pérez uses the expression “Pan-American jazz” to account for both the Afro-Cuban jazz tradition and non-Cuban Latin American fusions with jazz. Throughout this dissertation, I unpack the notion of Pan-American jazz from a variety of theoretical perspectives including Latinx identity discourse, transcription and musical analysis, and hybridity theory. -

The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music from the Dean

WINTER 2012 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music From the Dean On behalf of the College of Fine and Applied Arts, I want to congratulate the School of Music on a year of outstanding accomplishments and to WINTER 2012 thank the School’s many alumni and friends who Published for alumni and friends of the School of Music at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. have supported its mission. The School of Music is a unit of the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and has been an accredited institutional member of the National While it teaches and interprets the music of the past, the School is committed Association of Schools of Music since 1933. to educating the next generation of artists and scholars; to preserving our artistic heritage; to pursuing knowledge through research, application, and service; and Karl Kramer, Director Joyce Griggs, Associate Director for Academic Affairs to creating artistic expression for the future. The success of its faculty, students, James Gortner, Assistant Director for Operations and Finance J. Michael Holmes, Enrollment Management Director and alumni in performance and scholarship is outstanding. David Allen, Outreach and Public Engagement Director Sally Takada Bernhardsson, Director of Development Ruth Stoltzfus, Coordinator, Music Events The last few years have witnessed uncertain state funding and, this past year, deep budget cuts. The challenges facing the School and College are real, but Tina Happ, Managing Editor Jean Kramer, Copy Editor so is our ability to chart our own course. The School of Music has resolved to Karen Marie Gallant, Student News Editor Contributing Writers: David Allen, Sally Takada Bernhardsson, move forward together, to disregard the things it can’t control, and to succeed Michael Cameron, Tina Happ, B. -

Grover Washington, Jr. Feels So Good Mp3, Flac, Wma

Grover Washington, Jr. Feels So Good mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Feels So Good Country: Canada Released: 1981 Style: Soul-Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1344 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1563 mb WMA version RAR size: 1756 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 407 Other Formats: WMA AA XM MP3 VOC TTA WAV Tracklist Hide Credits The Sea Lion A1 5:59 Written-By – Bob James Moonstreams A2 5:58 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. Knucklehead A3 7:51 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. It Feels So Good B1 8:50 Written-By – Ralph MacDonald, William Salter Hydra B2 9:07 Written-By – Grover Washington, Jr. Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Quality Records Limited Distributed By – Quality Records Limited Credits Arranged By – Bob James Bass – Gary King (tracks: A1 to A3), Louis Johnson (tracks: B1, B2) Bass Trombone – Alan Ralph*, Dave Taylor* Cello – Charles McCracken, Seymour Barab Drums – Jimmy Madison (tracks: A3), Kenneth "Spider Webb" Rice* (tracks: B1, B2), Steve Gadd (tracks: A1, A2) Electric Piano – Bob James Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder English Horn – Sid Weinberg* Flugelhorn – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Randy Brecker, Bob Millikan* Guitar – Eric Gale Oboe – Sid Weinberg* Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Piano – Bob James Producer – Creed Taylor Saxophone [Soprano] – Grover Washington, Jr. Saxophone [Tenor] – Grover Washington, Jr. Synthesizer – Bob James Trombone – Barry Rogers Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Randy Brecker, Bob Millikan* Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – Barry Finclair, David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Guy Lumia, Harold Kohon, Harold Lookofsky*, Lewis Eley, Max Ellen, Raoul Poliakin Notes Recorded at Van Gelder Studios, May & July 1975 Manufactured and distributed in Canada M5-177V1 on cover & spine M 177V on labels Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Grover Feels So Good KU-24 S1 Kudu KU-24 S1 US 1975 Washington, Jr. -

Bob Marley Poems

Bob marley poems Continue Adult - Christian - Death - Family - Friendship - Haiku - Hope - Sense of Humor - Love - Nature - Pain - Sad - Spiritual - Teen - Wedding - Marley's Birthday redirects here. For other purposes, see Marley (disambiguation). Jamaican singer-songwriter The HonourableBob MarleyOMMarley performs in 1980BornRobert Nesta Marley (1945- 02-06)February 6, 1945Nine Mile, Mile St. Ann Parish, Colony jamaicaDied11 May 1981 (1981-05-11) (age 36)Miami, Florida, USA Cause of deathMamanoma (skin cancer)Other names Donald Marley Taff Gong Profession Singer Wife (s) Rita Anderson (m. After 1966) Partner (s) Cindy Breakspeare (1977-1978)Children 11 SharonSeddaDavid Siggy StephenRobertRohan Karen StephanieJulianKy-ManiDamian Parent (s) Norval Marley Sedella Booker Relatives Skip Marley (grandson) Nico Marley (grandson) Musical careerGenres Reggae rock Music Instruments Vocals Guitar Drums Years active1962-1981Labels Beverly Studio One JAD Wail'n Soul'm Upsetter Taff Gong Island Associated ActsBob Marley and WailersWebsitebobmarley.com Robert Nesta Marley, OM (February 6, 1945 - May 11, 1981) was Jamaican singer, songwriter and musician. Considered one of the pioneers of reggae, his musical career was marked by a fusion of elements of reggae, ska, and rocksteady, as well as his distinctive vocal and songwriting style. Marley's contribution to music has increased the visibility of Jamaican music around the world and has made him a global figure in popular culture for more than a decade. During his career, Marley became known as the Rastafari icon, and he imbued his music with a sense of spirituality. He is also considered a global symbol of Jamaican music and culture and identity, and has been controversial in his outspoken support for marijuana legalization, while he has also advocated for pan-African. -

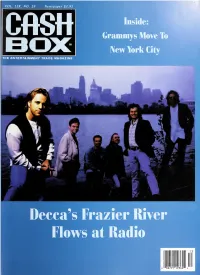

Flows at Radio

VOL. LIX, NO. 29 Newspaper $3.95 Inside: Grammys Move To New York City THE ENTERTAINMENT TRADE MAGAZINE Decca’s Frazier River Flows at Radio o 82791 19360 4 37 VOL. LIX, NO. 29 MARCH 30, 1996 STAFF rcwi«i;aawmga GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher KEITH ALBERT POP SINGLE THE ENTERTAINMENT TRADE MAGAZINE Exec. V.PJGeneral Manager Always Be My Baby M.R. MARTINEZ Managing Editor Mariah Carey EDITORIAL (Columbia) Los Angeles JOHN GOFF GIL ROBERTSON IV DAINA DARZIN HECTOR RESENDEZ. Latin Edtor URBAN SINGLE Nashville Cover Story WENDY NEWCOMER All Things... The New York Joe The Frazier River Flows J.S. GAER CHART RESEARCH (Island) Angeles Frazier River frontman Danny Frazier had a plan for his group of eclectic Los BRIAN PARMELLY musicians. He’d turn a saloon band into an act that would get signed to a major ZIV TONY RUIZ label. Doesn’t sound terribly original or uncommon, but the Decca recording act RAP SINGLE PETER FIRESTONE went from the River Saloon in Cincinnati, OH to a spot on the Cosh Box Country Nashville \A£>o-Hah! Got You... GAIL FRANCESCHI Singles chart and has been traveling the nation making folks at country radio spin MARKETING/ADVERTISING Busta Rhymes Nashville editor the single “She Got What She Deserves.” Wendy Newcomer Los Angeles (Elektra) talks with Frazier about the odyssey and the group’s prospects. FFiANK HIGGINBOTHAM JOHN RHYS —see page 5 BOB CASSELL Nashville COUNTRY SINGLE TED RANDALL Take A Stroll Near Hollywood And Vine New York You Can Feel Bad NOEL ALBERT Capitol New Media has, well, reinvented the famous intersection of Hollywood CIRCULATION Patty Loveless Arid Vine. -

The Annenberg Center Presents Eddie Palmieri Afro-Caribbean Jazz Quartet, May 7

NEW S FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 27, 2021 The Annenberg Center Presents Eddie Palmieri Afro-Caribbean Jazz Quartet, May 7 (Philadelphia – April 27, 2021) — The Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts presents legendary pianist and bandleader Eddie Palmieri and his Afro-Caribbean Jazz Quartet streamed live, on Friday, May 7 at 7 PM. Visit AnnenbergCenter.org for more information. Renowned NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri is at the top of his game. A beloved patriarch of Latin jazz, he has amassed nine Grammy® Awards while remaining on the cutting edge of Afro-Caribbean music since the early 1960s. Known for his bold charisma and innovative drive, Palmieri returns to the Annenberg Center stage with Luques Curtis on bass, Louis Fouché on alto saxophone, and Camilo Molina on drums. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Eddie Palmieri (Leader/Piano) Known as one of the finest pianists of the past 60 years, Eddie Palmieri is a bandleader, arranger and composer of salsa and Latin jazz. His playing skillfully fuses the rhythm of his Puerto Rican heritage with the complexity of his jazz influences including Thelonious Monk, Herbie Hancock, McCoy Tyner and his older brother, Charlie Palmieri. Palmieri’s parents emigrated from Ponce, Puerto Rico to New York City in 1926. Born in Spanish Harlem and raised in the Bronx, Palmieri learned to play the piano at an early age and at 13, he joined his uncle’s orchestra playing timbales. His professional career as a pianist took off with various bands in the early 1950s including Eddie Forrester, Johnny Segui and the popular Tito Rodríguez Orchestra.