Teaching Turtle Island Quartet Music: Selected String Orchestra Pieces for High School and College Musicians Sally Hernandez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ross Nickerson-Banjoroadshow

Pinecastle Recording Artist Ross Nickerson Ross’s current release with Pin- ecastle, Blazing the West, was named as “One of the Top Ten CD’s of 2003” by Country Music Television, True West Magazine named it, “Best Bluegrass CD of 2003” and Blazing the West was among the top 15 in ballot voting for the IBMA Instrumental CD of the Year in 2003. Ross Nickerson was selected to perform at the 4th Annual Johnny Keenan Banjo Festival in Ireland this year headlined by Bela Fleck and Earl Scruggs last year. Ross has also appeared with the New Grass Revival, Hot Rize, Riders in the Sky, Del McCoury Band, The Oak Ridge Boys, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and has also picked and appeared with some of the best banjo players in the world including Earl Scruggs, Bela Fleck, Bill Keith, Tony Trischka, Alan Munde, Doug Dillard, Pete Seeger and Ralph Stanley. Ross is a full time musician and on the road 10 to 15 days a month doing concerts , workshops and expanding his audience. Ross has most recently toured England, Ireland, Germany, Holland, Sweden and visited 31 states and Canada in 2005. Ross is hard at work writing new material for the band and planning a new CD of straight ahead bluegrass. Ross is the author of The Banjo Encyclopedia, just published by Mel Bay Publications in October 2003 which has already sold out it’s first printing. For booking information contact: Bullet Proof Productions 1-866-322-6567 www.rossnickerson.com www.banjoteacher.com [email protected] BLAZING THE WEST ROSS NICKERSON 1. -

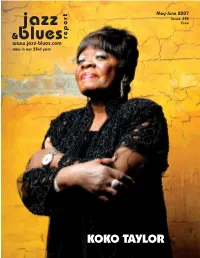

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Pure Acoustic

A TAYLOR GUITARS QUARTERLY PUBLICATION • VOLUME 47 • WINTER 2006 pure acoustic THE GS SERIES TAKES SHAPE I’m a 30-year-old mother and wife who Jorma Kaukonen, Bert Jansch, Leo Kottke, 1959 Harmony Sovereign to a collector, loves to play guitar. I currently own two Reverend Gary Davis, and others, and my I will buy that Taylor 110, or even a 200 Letters Fenders. But after seeing you recognize listeners tell me I am better than before series model, which are priced right. my kind of player, my next guitar will be the “incident”. That’s a long story about John-Hans Melcher a Taylor (keeping my fingers crossed for a great guitar saving my hand, my music, (former percussionist for Christmas). Thanks for thinking of me. and my job. Thanks for building your Elvis Presley and Ann-Margret) Via e-mail Bonnie Manning product like I build mine — with pride Via e-mail and quality materials. By the way, I saw Artie Traum conduct After many years of searching and try- Aloha, Mahalo Nui a workshop here in Wakefield and it was ing all manner of quality instruments in Loa, A Hui Hou a very good time. Artie is a fine musician order to improve on the sound and feel Aloha from Maui! I met David Hosler, and a real down-to-earth guy — my kind of, would you believe, a 1966 Harmony Rob Magargal, and David Kaye at Bounty of people. Sovereign, I’ve done it! It’s called a Taylor Music on Maui last August, and I hope Bob “Slice” Crawford 710ce-L9. -

Group Sales and Benefits

Group Sales and Benefits 2019–2020 SEASON Mutter by Bartek Barczyk / DG, Tilson Thomas by Spencer Lowell, Ma by Jason Bell, WidmannCover by photo Marco by Jeff Borggreve, Goldberg Wang by / Esto. Kirk Edwards, This page: Uchida Barenboim by Decca by Steve / Justin J. Sherman, Pumfrey, Kidjo Terfel by Sofia by Mitch Jenkins Sanchez / DG, & Mauro Muti Mongiello. by Todd Rosenberg Photography, Kaufmann by Julian Hargreaves / Sony Classical, Fleming by Andrew Eccles, Kanneh-Mason by Lars Borges, Group Benefits Bring 10 or more people to any Carnegie Hall presentation and enjoy exclusive benefits. Daniel Barenboim Tituss Burgess Group benefits include: • Discounted tickets for selected events • Payment flexibility • Waived convenience fees • Advance reservations before the general public Sir Bryn Terfel Riccardo Muti More details are listed on page 22. Calendar listings of all Carnegie Hall presentations throughout the 2019–2020 season are featured Jonas Kaufmann Renée Fleming on the following pages, including many that have discounted tickets available for groups. ALL GROUPS Save 10% when you purchase tickets to concerts identified with the 10% symbol.* Sheku Kanneh-Mason Anne-Sophie Mutter BOOK AND PAY For concerts identified with the 25% symbol, groups that pay at the time of their reservation qualify for a 25% discount.* STUDENT GROUPS Michael Tilson Thomas Yo-Yo Ma Pay only $10 per ticket for concerts identified with the student symbol.* * Discounted seats are subject to availability and are not valid on prior purchases or reservations. Selected seats and limitations apply. Jörg Widmann Yuja Wang [email protected] 212-903-9705 carnegiehall.org/groups Mitsuko Uchida Angélique Kidjo Proud Season Sponsor October Munich Philharmonic The Munich Philharmonic returns to Carnegie Hall for two exciting concerts conducted by Valery Gergiev. -

Download Booklet

559216-18 bk Bolcom US 12/08/2004 12:36pm Page 40 AMERICAN CLASSICS WILLIAM BOLCOM Below: Longtime friends, composer William Bolcom and conductor Leonard Slatkin, acknowledge the Songs of Innocence audience at the close of the performance. and of Experience (William Blake) Soloists • Choirs University of Michigan Above: Close to 450 performers on stage at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor, Michigan, under the School of Music baton of Leonard Slatkin in William Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Symphony Orchestra University Musical Society All photographs on pages 37-40 courtesy of Peter Smith/University Musical Society Leonard Slatkin 8.559216-18 40 559216-18 bk Bolcom US 12/08/2004 12:36pm Page 2 Christine Brewer • Measha Brueggergosman • Ilana Davidson • Linda Hohenfeld • Carmen Pelton, Sopranos Joan Morris, Mezzo-soprano • Marietta Simpson, Contralto Thomas Young, Tenor • Nmon Ford, Baritone • Nathan Lee Graham, Speaker/Vocals Tommy Morgan, Harmonica • Peter “Madcat” Ruth, Harmonica and Vocals • Jeremy Kittel, Fiddle The University Musical Society The University of Michigan School of Music Ann Arbor, Michigan University Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Kiesler, Music Director Contemporary Directions Ensemble/Jonathan Shames, Music Director University Musical Society Choral Union and University of Michigan Chamber Choir/Jerry Blackstone, Conductor University of Michigan University Choir/Christopher Kiver, Conductor University of Michigan Orpheus Singers/Carole Ott, William Hammer, Jason Harris, Conductors Michigan State University Children’s Choir/Mary Alice Stollak, Music Director Leonard Slatkin Special thanks to Randall and Mary Pittman for their continued and generous support of the University Musical Society, both personally and through Forest Health Services. Grateful thanks to Professor Michael Daugherty for the initiation of this project and his inestimable help in its realization. -

Violinoctet Violin First European Quintet Performs

ViolinOctetOctet New Voices for the 21st Century Volume 2, Number 6 Spring 2007 First European Quintet Performs says that van Laethem likes to participate in new and unusual concerts and performance set- tings, which gave Wouters the idea that van Laethem might be interested in the octet in- struments, which he was. Van Laethem is also a teacher at the Academie voor Muziek en Woord in Mol, and took it upon himself to fi nd others who would like to play the new instruments in concert. Jan Sciffer, who played the alto, is the cello in- structor at the Academy. All the other performers were stu- dents. The performers were enthusias- tic about the new instruments, and although the performance was planned to be a single event, the payers want to keep on playing them. A quintet of New Violin Family instruments in rehearsal in Belgium. (l to r) Bert van Laethem, soprano; Eveline Debie, mezzo; Jan Sciff er, alto; Jef Kenis, tenor; and Greg Brabers, baritone. The concert took place on February 10, 2007 at to Belgium via email; “Purcell’s Fantasia on One 8:00 p.m. in the Saint Peter and Paul Church in Note,” and the aria from Bach’s Cantata 124. Mol, Belgium, a small city about 40 km east of Antwerp. There were an estimated 200 people Before the ensemble played, the director of the attending, most of whom were local residents of school gave a short introduction. Wouters says it Mol. The quintet, which was made up of teach- was clear that this gentleman (name unavailable ers and students from a local music academy, at press time) had done his homework and had performed only a few selections because their carefully read all the information Wouters had performance was just one part of the music acad- given him. -

The Fiddler Magazine General Store Fiddler Magazine T-Shirt! Prices Listed in U.S

The Fiddler Magazine General Store Fiddler Magazine T-shirt! Prices listed in U.S. funds. Please note that credit card payments are only Be comfortable and attractive as accepted through PayPal (order online at www.fiddle.com). you fiddle around this summer. Featuring the Fiddler Magazine • Bonus with 3-year subscriptions: Get a free back issue of your choice! logo and the slogan “Fiddlers Please list 1st, 2nd, and 3rd choices on order form. don’t fret!” Thick, roomy, 100% BACK ISSUES (Only avail. issues are listed below. Quantities limited.) cotton. Sizes S, L, XL, XXL. Color: Oceana (blue/green). $10. Spring ’94: Martin Hayes; County Clare Fiddling; Laurie Lewis… Fall ’95: Donegal Fiddling; Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh; Canray Fontenot; Oliver Fall ’04: Judy Hyman; Brian Conway; Schroer; “Cindy” Lyrics; Fiddling in the 1700s; Fiddling Bob Taylor… Kyle & Lucy MacNeil; Knut Buen… Winter ’95/’96: Appalachian Fiddling; Charlie Acuff; Stéphane Grappelli; Violet Hen- Winter ’04/’05: Regina Carter; Séan Ryan; Mexico’s Son Huasteco… sley; Jess Morris: Texas Cowboy Fiddler; Violin Books; Learning Tips… Spring ’05: Svend Asmussen; Fiddle Music of the Civil War; Caoimhin O Raghal- Win. ’96/’97: Blues; Vassar Clements; Paul Anastasio; Bulgarian; Bob McQuillen… laigh; Jamie Laval; Pedro Dimas; Julie Lyonn Lieberman… Summer 97: Kentucky Fiddling; Bruce Greene; Stuart Duncan; Pierre Schryer; Summer ’05: Fiddlers of Bill Monroe; Bobby Hicks; Gene Lowinger; Richard Cowboy Fiddler Woody Paul… Greene; Earl White; Remembering Ralph Blizard; Starting and Running -

A Healing Return to the Stage for the Canton Symphony Orchestra by Tom Wachunas

A Healing Return to the Stage for the Canton Symphony Orchestra by Tom Wachunas Reasons to be cheerful: they’re back! The May 23 concert by the Canton Symphony Orchestra marked the first time in more than a year that the ensemble has performed live at Umstattd Performing Arts Hall. This occasion was certainly an important step on the road back to cultural “normalcy” as we recover from the dreadful pandemic shutdown. For a May 21 article by Ed Balint in The Repository (Canton’s daily newspaper), CSO president and CEO Michelle Charles said of the concert, “That’s what we do, that’s what we love and that’s why we exist, to perform music live. You do take for granted how readily available (classical music) is until it’s not. So I think it’s going to be very emotional.” Noting the special significance of the concert to Gerhardt Zimmermann, CSO music director and conductor since 1980, she added, “It’s been so long, and Canton has held a special place in his heart for many, many years. I think it’s going to be more emotional for him than anyone.” The emotional factor becomes even more resonant when considering Zimmermann’s own battle with coronavirus which led to weeks of hospitalization and rehabilitation in 2020. He’s still not at optimal strength, and consequently conducted the program while seated on a raised platform. This short concert (with no intermission) was an altogether unique sensory experience, and not a CSO business-as-usual affair. Zimmermann chose just two works to be on the program: Mendelssohn’s String Octet, and Mozart’s Symphony No. -

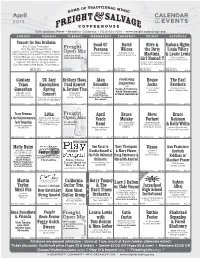

April CALENDAR of EVENTS

April CALENDAR 2013 OF EVENTS 2020 Addison Street • Berkeley, California • (510) 644-2020 • www.freightandsalvage.org SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY Concert for Sue Draheim eric & Suzy Thompson, Good Ol’ David Olive & Barbara Higbie, Jody Stecher & kate brislin, Freight laurie lewis & Tom rozum, kathy kallick, Persons Wilcox the Dirty Linda Tillery Open Mic California bluegrass the best of pop Gerry Tenney & the Hard Times orchestra, pay your dues, trailblazers’ reunion and folk aesthetics Martinis, & Laurie Lewis Golden bough, live oak Ceili band with play and shmooze Hills to Hollers the Patricia kennelly irish step dancers, Girl Named T album release show Tempest, Will Spires, Johnny Harper, rock ‘n’ roots fundraiser don burnham & the bolos, Tony marcus for the rex Foundation $28.50 adv/ $4.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $24.50 adv/ $20.50 adv/ $22.50 adv/ $30.50 door monday, April 1 $6.50 door Apr 2 $22.50 door Apr 3 $26.50 door Apr 4 $22.50 door Apr 5 $24.50 door Apr 6 Gautam UC Jazz Brittany Haas, Alan Celebrating House The Earl Songwriters Tejas Ensembles Paul Kowert Senauke with Jacks Brothers Zen folk musician, Caren Armstrong, “the rock band Outlaw Hillbilly Ganeshan Spring & Jordan Tice featuring Keith Greeninger without album release show Carnatic music string fever Jon Sholle, instruments” with distinction Concert from three Chad Manning, & Steve Meckfessel and inimitable style featuring the Advanced young virtuosos Suzy & Eric Thompson, Combos and big band Kate Brislin $20.50/$22.50 Apr 7 $14.50/$16.50 Apr -

Guitar Week, July 24-30, 2016 7:30- 8:30 Breakfast

JULY 3 - AUGUST 6, 2016 AT WARREN WILSON COLLEGE, ASHEVILLE, NC The Swannanoa Gathering Warren Wilson College, PO Box 9000, Asheville, NC 28815-9000 phone/fax: (828) 298-3434 email: [email protected] • website: www.swangathering.com shipping address: The Swannanoa Gathering, 701 Warren Wilson Rd., Swannanoa, NC 28778 For college admission information contact: [email protected] or 1-800-934-3536 WARREN WILSON COLLEGE CLASS INFORMATION President Dr. Steven L. Solnick The workshops take place at various sites around the Warren Wilson Vice President and Dean of the College Dr. Paula Garrett campus and environs, (contact: [email protected] or 1-800-934-3536 Vice President for Administration and Finance Stephanie Owens for college admission information) including classrooms, Kittredge Theatre, our Vice President of Advancement K. Johnson Bowles Bryson Gym dancehall and campus Pavilion, the campus gardens and patios, Vice President for Enrollment and Marketing Janelle Holmboe Dean of Student Life Paul Perrine and our own jam session tents. Each year we offer over 150 classes. Students are Dean of Service Learning Cathy Kramer free to create their own curriculum from any of the classes in any programs offered Dean of Work Ian Robertson for each week. Students may list a class choice and an alternate for each of our scheduled class periods, but concentration on two, or perhaps three classes is THE SWANNANOA GATHERING strongly recommended, and class selections are required for registration. We ask that you be thoughtful in making your selections, since we will consider Director Jim Magill them to be binding choices for which we will reserve you space. -

List of Works 2003

Christian Mason Full Works List 2003 – Present Date Piece Premiere Premiere Performer(s) / Subsequent Performances Date/Place Artist(s) ORCHESTRA In Preparation From Space the Earth is Blue… TBC Nathalie Forget, Ensemble Concerto for ondes martenot, soloist ensemble (8 l’Itinéraire, Orchestre players), chamber orchestra, female voice choice d’Auvergne and choir In Preparation New Commission 2021 - Lucerne Festival Academy c.20 mins. Donaueschingen Alumni Orchestra Symphony Orchestra, ondes martenot (tbc) Festival, Donaueschingen, Germany 2020 However long a time may pass…All things must 2020, June 4th, Konzerthausorchester Berlin 2020, June 5th – 6th, Berlin Konzerthaus, Germany yet meet again… Berlin Konzerthaus, (cond: Christoph Eschenbach) 21 mins. Berlin, Germany 2020, June 7th, Dortmund Konzerthaus, Germany Symphony Orchestra 2020, June 8th, Hamburg Elbphilharmonie, Germany 2020, June 20th, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Festival, Germany (tbc) 2019 Eternity in an hour 2019, April 27th, Wiener Philharmoniker (cond: 2019, April 28th, Musikverein, Golden Hall, Vienna, 15 mins. Musikverein, Golden Christian Thielemann) Austria Symphony Orchestra Hall, Vienna, Austria 2019, May 2nd, Berlin Dom, Berlin, Germany 2019 Eternal Return 2019, January 26th - hr-sinfonieorchester (cond: 7 mins. Breitkopf Festival Michal Nesterowicz) Symphony Orchestra Jubilee concert, Kurhaus Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, Germany 2018 Man Made 2018, May 24th, Royal Philharmonia, Anu Komsi 18 mins. Festival Hall (Music of (soprano) (cond: Gergely Soprano and Ensemble Today series),