In This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pure Acoustic

A TAYLOR GUITARS QUARTERLY PUBLICATION • VOLUME 47 • WINTER 2006 pure acoustic THE GS SERIES TAKES SHAPE I’m a 30-year-old mother and wife who Jorma Kaukonen, Bert Jansch, Leo Kottke, 1959 Harmony Sovereign to a collector, loves to play guitar. I currently own two Reverend Gary Davis, and others, and my I will buy that Taylor 110, or even a 200 Letters Fenders. But after seeing you recognize listeners tell me I am better than before series model, which are priced right. my kind of player, my next guitar will be the “incident”. That’s a long story about John-Hans Melcher a Taylor (keeping my fingers crossed for a great guitar saving my hand, my music, (former percussionist for Christmas). Thanks for thinking of me. and my job. Thanks for building your Elvis Presley and Ann-Margret) Via e-mail Bonnie Manning product like I build mine — with pride Via e-mail and quality materials. By the way, I saw Artie Traum conduct After many years of searching and try- Aloha, Mahalo Nui a workshop here in Wakefield and it was ing all manner of quality instruments in Loa, A Hui Hou a very good time. Artie is a fine musician order to improve on the sound and feel Aloha from Maui! I met David Hosler, and a real down-to-earth guy — my kind of, would you believe, a 1966 Harmony Rob Magargal, and David Kaye at Bounty of people. Sovereign, I’ve done it! It’s called a Taylor Music on Maui last August, and I hope Bob “Slice” Crawford 710ce-L9. -

Group Sales and Benefits

Group Sales and Benefits 2019–2020 SEASON Mutter by Bartek Barczyk / DG, Tilson Thomas by Spencer Lowell, Ma by Jason Bell, WidmannCover by photo Marco by Jeff Borggreve, Goldberg Wang by / Esto. Kirk Edwards, This page: Uchida Barenboim by Decca by Steve / Justin J. Sherman, Pumfrey, Kidjo Terfel by Sofia by Mitch Jenkins Sanchez / DG, & Mauro Muti Mongiello. by Todd Rosenberg Photography, Kaufmann by Julian Hargreaves / Sony Classical, Fleming by Andrew Eccles, Kanneh-Mason by Lars Borges, Group Benefits Bring 10 or more people to any Carnegie Hall presentation and enjoy exclusive benefits. Daniel Barenboim Tituss Burgess Group benefits include: • Discounted tickets for selected events • Payment flexibility • Waived convenience fees • Advance reservations before the general public Sir Bryn Terfel Riccardo Muti More details are listed on page 22. Calendar listings of all Carnegie Hall presentations throughout the 2019–2020 season are featured Jonas Kaufmann Renée Fleming on the following pages, including many that have discounted tickets available for groups. ALL GROUPS Save 10% when you purchase tickets to concerts identified with the 10% symbol.* Sheku Kanneh-Mason Anne-Sophie Mutter BOOK AND PAY For concerts identified with the 25% symbol, groups that pay at the time of their reservation qualify for a 25% discount.* STUDENT GROUPS Michael Tilson Thomas Yo-Yo Ma Pay only $10 per ticket for concerts identified with the student symbol.* * Discounted seats are subject to availability and are not valid on prior purchases or reservations. Selected seats and limitations apply. Jörg Widmann Yuja Wang [email protected] 212-903-9705 carnegiehall.org/groups Mitsuko Uchida Angélique Kidjo Proud Season Sponsor October Munich Philharmonic The Munich Philharmonic returns to Carnegie Hall for two exciting concerts conducted by Valery Gergiev. -

PROGRAM NOTES Guided Tour

13/14 Season SEP-DEC Ted Kurland Associates Kurland Ted The New Gary Burton Quartet 70th Birthday Concert with Gary Burton Vibraphone Julian Lage Guitar Scott Colley Bass Antonio Sanchez Percussion PROGRAM There will be no intermission. Set list will be announced from stage. Sunday, October 6 at 7 PM Zellerbach Theatre The Annenberg Center's Jazz Series is funded in part by the Brownstein Jazz Fund and the Philadelphia Fund For Jazz Legacy & Innovation of The Philadelphia Foundation and Philadelphia Jazz Project: a project of the Painted Bride Art Center. Media support for the 13/14 Jazz Series provided by WRTI and City Paper. 10 | ABOUT THE ARTISTS Gary Burton (Vibraphone) Born in 1943 and raised in Indiana, Gary Burton taught himself to play the vibraphone. At the age of 17, Burton made his recording debut in Nashville with guitarists Hank Garland and Chet Atkins. Two years later, Burton left his studies at Berklee College of Music to join George Shearing and Stan Getz, with whom he worked from 1964 to 1966. As a member of Getz's quartet, Burton won Down Beat Magazine's “Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition” award in 1965. By the time he left Getz to form his own quartet in 1967, Burton had recorded three solo albums. Borrowing rhythms and sonorities from rock music, while maintaining jazz's emphasis on improvisation and harmonic complexity, Burton's first quartet attracted large audiences from both sides of the jazz-rock spectrum. Such albums as Duster and Lofty Fake Anagram established Burton and his band as progenitors of the jazz fusion phenomenon. -

The “Second Quintet”: Miles Davis, the Jazz Avant-Garde, and Change, 1959-68

THE “SECOND QUINTET”: MILES DAVIS, THE JAZZ AVANT-GARDE, AND CHANGE, 1959-68 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Kwami Taín Coleman August 2014 © 2014 by Kwami T Coleman. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/vw492fh1838 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Karol Berger, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. MichaelE Veal, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Heather Hadlock I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Charles Kronengold Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost for Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. -

Best of the Beatles (Cello) Free

FREE BEST OF THE BEATLES (CELLO) PDF Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation | 94 pages | 12 Dec 2008 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9781423410492 | English | Milwaukee, United States Best of the Beatles - 2nd Edition Cello | Hal Leonard | Heidmusic Thomann is the largest online and mail order retailer for musical instruments, light and sound equipment worldwide, having about 10m customers in countries and 80, products on offer. We are musicians ourselves and share your passion for making it. As a company, we have a single objective: making you, our customer, happy. We Best of the Beatles (Cello) a wide variety of pages giving information and enabling you to contact us before and after your purchase. Alternatively, please feel free to use our accounts on social media such as Facebook or Twitter to get in touch. Most members of our service staff are musicians themselves, which puts them in the perfect position to help you with everything from your choice of instruments to maintenance and repair issues. Our expert departments and workshops allow us to offer you professional advice and rapid maintenance and repair services. This also affects the price - to our customers' benefit, of course. Apart from the shop, you can discover a wide variety of additional things Best of the Beatles (Cello) forums, apps, blogs, and much more. Always with customised added value for musicians. Plugin Collection Consists of over 65 software instruments, software effects and 24 expansions, Over 35, sounds, Includes i. Boss Pocket GT Guitar Multi-FX, electric guitar multi effects, light and compact, YouTube has become the most popular music learning source for guitarists, the Pocket GT makes working with the platform's content easier and more productive than ever. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Summer Recreation Guide

Registration begins April 29, 2021 | Para ayuda en español: 414.475.8180 Recreation SUMMER Guide Activities for the entire community YOUTH | TEENS | ADULTS | SENIORS mkerec.net Join Milwaukee Recreation for summer fun in the sun! Warmer temperatures have arrived in Milwaukee, which Now is the perfect opportunity to try something new, means it’s time for the Summer 2021 Recreation Guide! We so take some time to browse our guide as there is are excited to offer much needed recreation activities to something for everyone. We look forward to safely the community this season. As always, the safety of our staff engaging with you this summer! and participants remains our top priority, and programs will continue to operate at a limited capacity and adhere Sincerely, to recommended physical distancing and mask-wearing guidelines. Dr. Keith P. Posley This summer, we are thrilled to welcome back many of our Superintendent of Schools most popular programs such as youth sports clinics, aquatics classes, wellness programs, and our summer playgrounds. You can also visit one of our many wading pools or splash pads — they’re a great way to beat the heat! Additionally, we invite you and your family to join us for the first ever Milwaukee Recreation Drive-in Movie Night! This new event will take place on May 15 and allow you to experience a classic summer drive-in at the Milwaukee Public Schools Central Services parking lot (5225 W. Vliet Street). More details regarding registration, movie selection, and start times can be found at mkerec.net/movie. OPENING BEFORE- AND -AFTER SCHOOL SOON CAMP Education and recreation enrichment activities for all grades LEARN MORE TODAY Scan the QR code or visit mkerec.net/camps $5 SWIM IS back! This summer, Milwaukee Recreation is excited to welcome back our $5 swim program! As the American Red Cross celebrates its centennial swim campaign, Milwaukee Recreation has partnered with the Red Cross to offer $5 swim classes at three (3) locations: Milwaukee HS of the Arts, North Division HS, and Vincent HS. -

Bethany Beach 2019 Summer Schedule

Bethany Beach 2019 Summer Schedule Bandstand Beach Events Bandstand shows begin at 7:30 pm unless otherwise noted. The Best Summer Vacation veterans formed in 1990 to back soul Spot in Delaware! Bettenroo singer extraordinaire, Leroy Hawkes. Fri, June 7 leroyhawkesandthehipnotics.com We agree with Microsoft News’ ranking Locals Anne Davey of Bethany Beach as the best summer and Lori Jacobs Lights Out vacation spot in Delaware. Keep invite you to Frankie Valli watching as we add year-round events. connect with them Tribute as they share covers from popular artists Sun, June 16 Poseidon Festival and originals from their CD release, Live LIGHTS OUT is a Memorial Day Weekend Out Loud. bettenroo.com four-part vocal group that is being Seaside Craft Show Real Diamond hailed as "America's #1 Tribute to Frankie First Saturday in June Sat, June 8 Valli and the Four Seasons". Real Diamond is a lightsoutvocals.com Summer Concert Series professional tribute Weekends June to Labor Day, 7:30 pm band dedicated to the th faithful re-creation of The 19 Street Movies on the Beach off Garfield Parkway the live Neil Band Mondays, June – August, dusk Diamond experience. Fri, June 21 realdiamondband.com Characterized by high energy and strong vocal Movies on the Bandstand Fridays in September, dusk harmonies, The 19th Sarah Williams Street Band delivers a fusion of Sun, June 9 Kids Club Sarah Williams is a Americana, country, and rock. The band Wednesdays in July Nashville singer- has shared the stage with country music Nature Center Saturdays (year-round) songwriter and pianist stars such as Rodney Atkins, Craig who voices her stories Morgan, and Chuck Mead. -

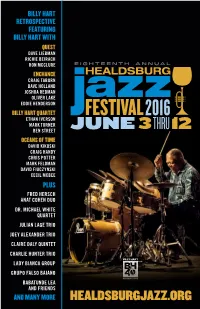

Billy Hart Retrospective Featuring Billy Hart with Plus and Many More

BILLY HART RETROSPECTIVE FEATURING BILLY HART WITH QUEST DAVE LIEBMAN RICHIE BEIRACH RON MCCLURE ENCHANCE CRAIG TABORN DAVE HOLLAND JOSHUA REDMAN OLIVER LAKE EDDIE HENDERSON BILLY HART QUARTET ETHAN IVERSON MARK TURNER BEN STREET OCEANS OF TIME DAVID KIKOSKI CRAIG HANDY CHRIS POTTER MARK FELDMAN DAVID FIUCZYNSKI CECIL MCBEE PLUS FRED HERSCH ANAT COHEN DUO DR. MICHAEL WHITE QUARTET JULIAN LAGE TRIO JOEY ALEXANDER TRIO CLAIRE DALY QUINTET CHARLIE HUNTER TRIO LADY BIANCA GROUP GRUPO FALSO BAIANO BABATUNDE LEA AND FRIENDS AND MANY MORE So many great jazz masters have had tributes to their talent and contributions, I felt one for Billy was way overdue. He is truly one of the greatest drummers in jazz history. He has been on thousands of recordings over his 50-year career and, in turn, has enhanced the careers of several exceptional musicians. He has also been a true friend to Healdsburg Jazz Festival, performing here 11 out of the past 17 years. Many people do not know his deep contributions to jazz and the vast number of musicians he has performed and recorded with over the years as leader, sideman and collaborator: Shirley Horn, Wes Montgomery, Betty Carter, Jimmy Smith, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Stan Getz, and so many more (see the Billy Hart discography on our website). When he began to lead his own bands in 1977, they proved to be both disciplined and daring. For this tribute, we will take you through his musical history, and showcase his deep passion for jazz and the breadth of his achievements. -

Creative Exploration of Eclecticism Applied to Bowed String Instruments with Special Emphasis on Cellos

The University of Adelaide Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts Creative exploration of eclecticism applied to bowed string instruments with special emphasis on cellos: Portfolio of original compositions and exegesis by Stephan Richter submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Adelaide, June 2016 1 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Declaration 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter listing of DVD recordings 7 Introduction 8 PART A Portfolio of original works: 17 A1. Marimbello, for marimba and violoncello 19 A2. Camino Trio, for piano, violin and violoncello 37 1. Camino Ventoso 2. El Valle del Dolor 3. Tiempo Intemporal A3. Trilogy, for eight violoncelli and percussion 69 1. Waiting for a sign 2. More or Lesser Antilles 3. Bamboozled A4. Son Montucello, per due violoncelli 107 A5. Kaleidoscope, Concerto per due violoncelli 117 2 PART B Exegesis 183 B1. Stylistic eclecticism 184 B2. Commentaries on the first four works 201 B3. Commentary Kaleidoscope 230 Conclusion 255 List of Sources 257 Musical Scores, Discography and Videos, Bibliography 3 NOTE: 1 DVD containing 'Recorded Performances' is included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. The DVD must be viewed in the Library. ABSTRACT This submission for the degree of Master of Philosophy in musical composition at the Elder Conservatorium of Music, University of Adelaide, consists of a portfolio of original compositions supported by an explanatory exegesis. The central concept for the creative exploration represented by these works is the idea of composing for bowed string instruments, cellos in particular, in a stylistically eclectic manner that will confront classically trained performers with rhythms drawn from a wide range of non-classical and non-European musical traditions. -

Downbeat.Com July 2010 U.K. £3.50

.K. £3.50 .K. u downbeat.com July 2010 2010 July DownBeat Victor Wooten // clauDio RoDiti // Frank Vignola // Duke RoBillarD // John Pizzarelli // henry ThreaDgill July 2010 JULY 2010 Volume 77 – Number 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser AdVertisiNg Sales Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] offices 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] customer serVice 877-904-5299 [email protected] coNtributors Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Marga- sak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Nor- man Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Go- logursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer Odell, Dan Ouellette,