Environmental Labeling Issues, Policies, and Practices Worldwide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Assessment Report on Microplastics

An Assessment Report on Microplastics This document was prepared by B Stevens, North Carolina Coastal Federation Table of Contents What are Microplastics? 2 Where Do Microplastics Come From? 3 Primary Sources 3 Secondary Sources 5 What are the Consequences of Microplastics? 7 Marine Ecosystem Health 7 Water Quality 8 Human Health 8 What Policies/Practices are in Place to Regulate Microplastics? 10 Regional Level 10 Outer Banks, North Carolina 10 Other United States Regions 12 State Level 13 Country Level 14 United States 14 Other Countries 15 International Level 16 Conventions 16 Suggested World Ban 17 International Campaigns 18 What Solutions Already Exist? 22 Washing Machine Additives 22 Faucet Filters 23 Advanced Wastewater Treatment 24 Plastic Alternatives 26 What Should Be Done? 27 Policy Recommendations for North Carolina 27 Campaign Strategy for the North Carolina Coastal Federation 27 References 29 1 What are Microplastics? The category of ‘plastics’ is an umbrella term used to describe synthetic polymers made from either fossil fuels (petroleum) or biomass (cellulose) that come in a variety of compositions and with varying characteristics. These polymers are then mixed with different chemical compounds known as additives to achieve desired properties for the plastic’s intended use (OceanCare, 2015). Plastics as litter in the oceans was first reported in the early 1970s and thus has been accumulating for at least four decades, although when first reported the subject drew little attention and scientific studies focused on entanglements, ‘ghost fishing’, and ingestion (Andrady, 2011). Today, about 60-90% of all marine litter is plastic-based (McCarthy, 2017), with the total amount of plastic waste in the oceans expected to increase as plastic consumption also increases and there remains a lack of adequate reduce, reuse, recycle, and waste management tactics across the globe (GreenFacts, 2013). -

FAQ About Recycling Cartons

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT CARTONS WHAT IS A CARTON? » Cartons are a type of packaging for food and beverage products you can purchase at the store. They are easy to recognize and are available in two types—shelf-stable and refrigerated. Shelf-stable cartons (types of products) Refrigerated (types of products) » Juice » Milk » Milk » Juice » Soy Milk » Cream » Soup and broth » Egg substitutes » Wine You will find these You will find these products in the chilled products on the shelves sections of grocery stores. in grocery stores. WHAT ARE CARTONS MADE FROM? » Cartons are mainly made from paper in the form of paperboard, as well as thin layers of polyethylene (plastic) and/or aluminum. Shelf-stable cartons contain on average 74% paper, 22% polyethylene and 4% aluminum. Refrigerated cartons contain about 80% paper and 20% polyethylene. ARE CARTONS RECYCLABLE? » Yes! Cartons are recyclable. In fact, the paper fiber contained in cartons is extremely valuable and useful to make new products. WHERE CAN I RECYCLE CARTONS? » To learn if your community accepts cartons for recycling, please visit RecycleCartons.com or check with your local recycling program. HOW DO I RECYCLE CARTONS? » Simply place the cartons in your recycle bin. If your recycling program collects materials as “single- stream,” you may place your cartons in your bin with all the other recyclables. If your recycling program collects materials as “dual-stream” (paper items together and plastic, metal and glass together), please place cartons with your plastic, metal and glass containers. WAIT, YOU JUST SAID CARTONS ARE MADE MAINLY FROM PAPER. Don’t I WANT TO PUT THEM WITH OTHER PAPER RECYCLABLES? » Good question. -

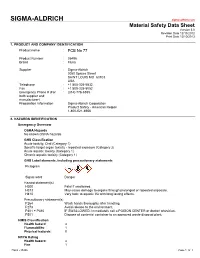

SIGMA-ALDRICH Sigma-Aldrich.Com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013

SIGMA-ALDRICH sigma-aldrich.com Material Safety Data Sheet Version 5.0 Revision Date 12/13/2012 Print Date 12/10/2013 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name : PCB No 77 Product Number : 35496 Brand : Fluka Supplier : Sigma-Aldrich 3050 Spruce Street SAINT LOUIS MO 63103 USA Telephone : +1 800-325-5832 Fax : +1 800-325-5052 Emergency Phone # (For : (314) 776-6555 both supplier and manufacturer) Preparation Information : Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Product Safety - Americas Region 1-800-521-8956 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Emergency Overview OSHA Hazards No known OSHA hazards GHS Classification Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 1) Specific target organ toxicity - repeated exposure (Category 2) Acute aquatic toxicity (Category 1) Chronic aquatic toxicity (Category 1) GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H300 Fatal if swallowed. H373 May cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. H410 Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects. Precautionary statement(s) P264 Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P273 Avoid release to the environment. P301 + P310 IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a POISON CENTER or doctor/ physician. P501 Dispose of contents/ container to an approved waste disposal plant. HMIS Classification Health hazard: 4 Flammability: 1 Physical hazards: 0 NFPA Rating Health hazard: 4 Fire: 1 Fluka - 35496 Page 1 of 7 Reactivity Hazard: 0 Potential Health Effects Inhalation May be harmful if inhaled. May cause respiratory tract irritation. Skin May be harmful if absorbed through skin. May cause skin irritation. Eyes May cause eye irritation. Ingestion May be fatal if swallowed. 3. COMPOSITION/INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Synonyms : 3,3′,4,4′-PCB 3,3′,4,4′-Tetrachlorobiphenyl Formula : C12H6Cl4 Molecular Weight : 291.99 g/mol No ingredients are hazardous according to OHSA criteria. -

Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health

COUNTY HEALTH RANKINGS WORKING PAPER DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES FOR ASSIGNING WEIGHTS TO DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH Bridget C. Booske Jessica K. Athens David A. Kindig Hyojun Park Patrick L. Remington FEBRUARY 2010 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................................................................... 4 Weighting Schemes Used by Other Rankings ............................................................................................... 5 Analytic Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Pragmatic Approach .......................................................................................................................................... 8 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix 1: Weighting in Other Rankings .................................................................................................. 11 Appendix 2: Analysis of 2010 County Health Rankings Dataset ............................................................ -

Corrugated Board Structure: a Review M.C

ISSN: 2395-3594 IJAET International Journal of Application of Engineering and Technology Vol-2 No.-3 Corrugated Board Structure: A Review M.C. Kaushal1, V.K.Sirohiya2 and R.K.Rathore3 1 2 Assistant Prof. Mechanical Engineering Department, Gwalior Institute of Information Technology,Gwalior, Assistant Prof. Mechanical Engineering 3 Departments, Gwalior Engineering College, Gwalior, M. Tech students Maharanapratap College of Technology, Gwalior, [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Corrugated board is widely used in the packing industry. The main advantages are lightness, recyclability and low cost. This makes the material the best choice to produce containers devoted to the shipping of goods. Furthermore examples of structure design based on corrugated boards can be found in different fields. Structural analysis of paperboard components is a crucial topic in the design of containers. It is required to investigate their strength properties because they have to protect the goods contained from lateral crushing and compression loads due to stacking. However in this paper complete and detailed information are presented. Keywords: - corrugated boards, recyclability, compression loads. Smaller flutes offer printability advantages as well as I. INTRODUCTION structural advantages for retail packaging. Corrugated board is essentially a paper sandwich consisting of corrugated medium layered between inside II. HISTORY and outside linerboard. On the production side, corrugated In 1856 the first known corrugated material was patented is a sub-category of the paperboard industry, which is a for sweatband lining in top hats. During the following four sub-category of the paper industry, which is a sub-category decades other forms of corrugated material were used as of the forest products industry. -

Tyvek Graphics Technical Data Sheet

DuPont ™ Tyvek ® for Graphics DURABLE – ECO-FRIENDLY – RECYCLABLE Available in sheets or rolls; usable for nearly all print technolo gies DuPont Tyvek a is a tough, durable, eco-friendly and 100% recyclable material available in sheets and rolls for all print technologies. DuPont Tyvek ® products are used for long-lasting signs, banners, flags, displays, visual merchandising, map and book printing, packaging, credit card sleeves, envelopes, shopping bags, wallets, wall coverings, drapery, and promotional apparel. Tyvek ® is also gaining use as a template material for signs because it is lightweight, durable, and is unaffected by moisture. Conventional laser printing is not recommended on Tyvek ® because of the temperatures involved in the printing units. For the same reason, Tyvek ® should not be used in electrostatic copiers. PRODUCT TYPE OF PRINTING USED FOR COATED MILS OZ. [GSM] CORE NOTES IDEAL USES STOCK WIDTHS Black Tyvek Flexography, Gravure, Offset Uncoated 5 mil 1.25 oz 2” Paper-like. Banners & Signs 36", 45" Lithography, Screen Process, UV-cure [42 gsm] Hard Structure Custom sizes available Inkjet (w/ testing due to lighter weight) Available in 10-yard rolls 1085D Digital on Demand, Flexography, Uncoated 10.3 mil 3.2 oz 3” Paper-like. Banners & Signs. Extra body 48.25", 57.125", 114.25" Gravure, Offset Lithography, Screen [109 gsm] Hard Structure for shape development. Custom sizes available Process, UV-cure Inkjet Available in 10-yard rolls 1079 Digital on Demand, Flexography, Uncoated 7.9 mil 2.85 oz 3” Paper-like. Tags & Labels 48" Gravure, Offset Lithography, Screen [97 gsm] Hard Structure Custom sizes available Process, Thermal Transfer, UV-cure Available in 10-yard rolls Inkjet 1073D Digital on Demand, Flexography, Uncoated 7.5 mil 2.2 oz 3” Paper-like. -

RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS: a Guide for Homeowners, Homebuyers, Landlords and Tenants 2011

CALIFORNIA ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS: A Guide For Homeowners, Homebuyers, Landlords and Tenants 2011 This guide was originally developed by M. B. Gilbert Associates, under contract with the California Department of Real Estate in cooperation with the California Department of Health Services. The 2005 edition was prepared by the California Department of Toxic Substances Control, in cooperation with the California Air Resources Board and the California Department of Health Services, and meets all State and Federal guidelines and lead disclosure requirements pursuant to the Residential Lead-Based Paint Hazard Reduction Act of 1992. The 2005 edition incorporates the Federal “Protect Your Family from Lead” pamphlet. The 2011 update was developed California Department of Toxic Substances Control. This booklet is offered for information purposes only, not as a reflection of the position of the administration of the State of California. Residential Environmental Hazards Booklet Page 1 of 48 January 2011 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER I ASBESTOS 3 CHAPTER II CARBON MONOXIDE 10 CHAPTER III FORMALDEHYDE 13 CHAPTER IV HAZARDOUS WASTE 17 CHAPTER V HOUSEHOLD HAZARDOUS WASTE 21 CHAPTER VI LEAD 24 CHAPTER VII MOLD 31 CHAPTER VIII RADON 36 APPENDIX A LIST OF FEDERAL AND STATE AGENCIES 42 APPENDIX B GLOSSARY 46 Residential Environmental Hazards Booklet Page 2 of 48 January 2011 Introduction The California Departments of Real Estate and Health Services originally prepared this booklet in response to the California legislative mandate (Chapter 969, Statutes of 1989, AB 983, Bane) to inform the homeowner and prospective homeowner about environmental hazards located on and affecting residential property. -

Implementation of Plastic Fusing Method to Upcycle Products of Plastic Waste

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 197 5th Bandung Creative Movement International Conference on Creative Industries 2018 (5th BCM 2018) Implementation of Plastic Fusing Method to Upcycle Products of Plastic Waste Terbit Setya Pambudi1*, Yanuar Herlambang2, Fajar Sadika3 1School Of Creative Industries, Telkom University, Bandung, Indonesia Abstract. Plastic waste is one of the most numerous in number, approximately 10 % of the total waste in the world. Plastic packaging, grocery bags, and home furnishings are the types that often found. There have been many efforts to reduce the amount of waste and the impact it causes, one of them is the up-cycling method. Up-cycling is the utilization method of waste products that have more value or new. By using this method, in addition to being able to reduce the plastic waste amount while creating new products with new value and functionality, namely small wallets, shopping bags, backpacks, gadgets sleeve etc. One method of up- cycling plastic is plastic fusing methods that uses heat and plastic waste to create new materials with thickness and strength. The current utilization of plastic waste has been undertaken by communities to produce a product, namely craftsman group named Kunarti but less variety of processing methods, limited to knitting method only. Based on the phenomenon, this research was conducted to find out how the application of the plastic fusing method so that it can be easily done, and into alternative methods of up- cycling which is can be applied by the craftsmen community in Bandung. Keywords: plastic fusing, plastic waste, upcycle 1 Introduction One of the largest contributors to household waste is plastic. -

Label Liners: Meeting the Sustainability Challenge

Label liners: meeting the sustainability challenge By Mariya Nedelcheva, Product Manager Film & With ever-greater emphasis placed on packaging and waste reduction, Jenny Wassenaar, Compliance & Sustainability brand owners are looking for solutions that secure their sustainability Director, Avery Dennison credentials. Consumers pay particularly close attention to packaging, where there are significant environmental gains to be made. For example, waste from labelling can create useful by-products and circular economies. Waste is not always visible on the final packaging, but its impact on brand reputation is no less real. Consumers’ perceptions of a brand can be enhanced when sustainability is improved. label.averydennison.com Matrix Liner Final White paper waste waste label 16% 35% 37% Start-up waste plus Challenge printed End-user The challenge of recycling waste from the labelling process in error scrap - and ideally creating useful by-products - is complex. Many 10% 1% different elements must be addressed in order to move towards the ultimate goal of zero waste. For example, the word ‘recyclable’ can mean many things, and should not be viewed in isolation. Today there is a chance that recyclable products will still end up in landfill, so what matters is establishing genuinely viable end-to-end recycling solutions. That means considering every component within packaging, including where it comes from, how much material has been used, and what happens at every stage of the package’s journey through the value chain. This paper discusses how the sustainability of labelling laminates can be improved, with a particular focus on the label release liners that are left behind once labels have been dispensed. -

Endocrine Disruption: Where Are We with Hazard and Risk Assessment? 2

1 Title: Endocrine disruption: where are we with hazard and risk assessment? 2 3 Running head: Hazard and risk assessment of endocrine disrupters 4 Katherine Coady*†, Peter Matthiessen‡, Holly M. Zahner§1, Jane Staveleyǁ; Daniel J. Caldwell#; 5 Steven L. Levine††, Leon Earl Gray Jr‡‡, Christopher J. Borgert§§ 6 7 † The Dow Chemical Company, Midland, MI, USA; 8 Telephone: 989-636-7423; Fax: 989-638-2425; e-mail: [email protected]; ‡Independent 9 Consultant, Llanwrtyd Wells, UK; e-mail: [email protected] ; § United States 10 Food and Drug Administration, Center for Veterinary Medicine, Rockville, MD, USA; email: 11 [email protected] ; ǁExponent Inc., Cary, NC, USA; email: [email protected] ; 12 #Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA; email [email protected] ; 13 ††Monsanto Company, St. Louis, MO, USA;email [email protected]; ‡‡USEPA, 14 ORD, NHEERL, TAD, RTB. RTP, NC, USA; email: [email protected] ; §§Applied 15 Pharmacology and Toxicology, Inc., and, Center for Environmental and Human Toxicology, 16 University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA; e-mail: [email protected] 17 1The views presented in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Food and Drug 18 Administration 19 * Corresponding Author: 20 Katherine Coady 21 The Dow Chemical Company, 1803 Building, Washington Street, Midland MI, USA, 48674. 22 Email address: [email protected] PeerJ Preprints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2580v1 | CC0 Open Access | rec: 4 Nov 2016, publ: 23 24 ABSTRACT 25 Approaches to assessing endocrine disruptors (EDs) differ across the globe, with some 26 regulatory environments using a hazard-based approach, while others employ risk-based 27 analyses. -

Economics of Food Labeling

Economics of Food Labeling. By Elise Golan, Fred Kuchler, and Lorraine Mitchell with contributions from Cathy Greene and Amber Jessup. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Economic Report No. 793. Abstract Federal intervention in food labeling is often proposed with the aim of achieving a social goal such as improving human health and safety, mitigating environmental hazards, averting international trade disputes, or supporting domestic agricultural and food manufacturing industries. Economic theory suggests, however, that mandatory food-labeling requirements are best suited to alleviating problems of asymmetric information and are rarely effective in redressing environmental or other spillovers associated with food production and consumption. Theory also suggests that the appropriate role for government in labeling depends on the type of information involved and the level and distribution of the costs and benefits of providing that information. This report traces the economic theory behind food labeling and presents three case studies in which the government has intervened in labeling and two examples in which government intervention has been proposed. Keywords: labeling, information policy, Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, dolphin-safe tuna, national organic standards, country-of-origin labels, biotech food labeling Acknowledgments We wish to thank Lorna Aldrich, Pauline Ippolito, Clark Nardinelli, Donna Roberts, and Laurian Unnevehr for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We appreciate the guidance provided by Nicole Ballenger, Mary Bohman, Margriet Caswell, Steve Crutchfield, Carol Jones, Kitty Smith, and John Snyder. We thank Tom McDonald for providing his editorial expertise. Elise Golan and Fred Kuchler are economists in the Food and Rural Economics Division, ERS. -

Packaging-Related Food Losses and Waste: an Overview of Drivers and Issues

Review Packaging-Related Food Losses and Waste: An Overview of Drivers and Issues Bernhard Wohner *, Erik Pauer, Victoria Heinrich and Manfred Tacker Section of Packaging and Resource Management, FH Campus Wien (University of Applied Sciences), 1030 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (E.P.); [email protected] (V.H.); [email protected] (M.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-1-606-6877-3572 Received: 4 December 2018; Accepted: 31 December 2018; Published: 7 January 2019 Abstract: Packaging is often criticized as a symbol of today’s throwaway society, as it is mostly made of plastic, which is in itself quite controversial, and is usually used only once. However, as packaging’s main function is to protect its content and 30% of all food produced worldwide is lost or wasted along the supply chain, optimized packaging may be one of the solutions to reduce this staggering amount. Developing countries struggle with losses in the supply chain before food reaches the consumer. Here, appropriate packaging may help to protect food and prolong its shelf life so that it safely reaches these households. In developed countries, food tends to be wasted rather at the household’s level due to wasteful behavior. There, packaging may be one of the drivers due to inappropriate packaging sizes and packaging that is difficult to empty. When discussing the sustainability of packaging, its protective function is often neglected and only revolves around the type and amount of material used for production. In this review, drivers, issues, and implications of packaging-related food losses and waste (FLW) are discussed, as well as the implication for the implementation in life cycle assessments (LCA).