The Curtain in Classical Sanskrit Drama "

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: a Study

Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Portrayal of Family Ties in Ancient Sanskrit Plays: A Study Dr. C. S. Srinivas Assistant Professor of English Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Technology Hyderabad India Abstract The journey of the Indian dramatic art begins with classical Sanskrit drama. The works of the ancient dramatists Bhasa, Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti and others are the products of a vigorous creative energy as well as sustained technical excellence. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists addressed several issues in their plays relating to individual, family and society. All of them shared a common interest— familial and social stability for the collective good. Thus, family and society became their most favoured sites for weaving plots for their plays. Ancient Sanskrit dramatists with their constructive idealism always portrayed harmonious filial relationships in their plays by persistently picking stories from the two great epics Ramayana and Mahabharata and puranas. The paper examines a few well-known ancient Sanskrit plays and focuses on ancient Indian family life and also those essential human values which were thought necessary and instrumental in fostering harmonious filial relationships. Keywords: Family, Filial, Harmonious, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Sanskrit drama. _______________________________________________________________________ http://www.ijellh.com 224 Volume II, Issue VIII, December 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 The ideals of fatherhood and motherhood are cherished in Indian society since the dawn of human civilization. In Indian culture, the terms ‘father’ and ‘mother’ do not have a limited sense. ‘Father’ does not only mean the ‘male parent’ or the man who is the cause of one’s birth. In a broader sense, ‘father’ means any ‘elderly venerable man’. -

Buddhacarita

CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY Life of the Buddka by AsHvaghosHa NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS & JJC EOUNDATION THE CLAY SANSKRIT LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JOHN & JENNIFER CLAY GENERAL EDITORS RICHARD GOMBRICH SHELDON POLLOCK EDITED BY ISABELLE ONIANS SOMADEVA VASUDEVA WWW.CLAYSANSBCRITLIBRARY.COM WWW.NYUPRESS.ORG Copyright © 2008 by the CSL. All rights reserved. First Edition 2008. The Clay Sanskrit Library is co-published by New York University Press and the JJC Foundation. Further information about this volume and the rest of the Clay Sanskrit Library is available at the end of this book and on the following websites: www.ciaysanskridibrary.com www.nyupress.org ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) Artwork by Robert Beer. Typeset in Adobe Garamond at 10.2$ : 12.3+pt. XML-development by Stuart Brown. Editorial input from Linda Covill, Tomoyuki Kono, Eszter Somogyi & Péter Szântà. Printed in Great Britain by S t Edmundsbury Press Ltd, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on acidffee paper. Bound by Hunter & Foulis, Edinburgh, Scotland. LIFE OF THE BUDDHA BY ASVAGHOSA TRANSLATED BY PATRICK OLIVELLE NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS JJC FOUNDATION 2008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Asvaghosa [Buddhacarita. English & Sanskrit] Life of the Buddha / by Asvaghosa ; translated by Patrick Olivelle.— ist ed. p. cm. - (The Clay Sanskrit library) Poem. In English and Sanskrit (romanized) on facing pages. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8147-6216-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8147-6216-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Gautama Buddha-Poetry. I. Olivelle, Patrick. II. -

URUBHANGAM (BREAKING of THIGHS) – a TRAGEDY in INDIAN TRADITION Bhagvanbhai H.Chaudhari, Ph. D. Assoc. Professor, Dept. Of

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ DR. BHAGVANBHAI H. CHAUDHARI (5683-5688) URUBHANGAM (BREAKING OF THIGHS) – A TRAGEDY IN INDIAN TRADITION Bhagvanbhai H.Chaudhari, Ph. D. Assoc. Professor, Dept. of English, The KNSBL Arts and Commerce College, Kheralu Gujarat (India) Scholarly Research Journal's is licensed Based on a work at www.srjis.com By and large a play is considered an „imitation of folk-attitude‟ wherein the outcome of human activity may either be happy or unhappy. Since the time of ancient Greek literature in the West, the drama has been categorized as comedy and tragedy. But Bharat Muni in his Natyashastra projected it to be: (एतद्रसेषु भावेषु सववकमवक्रियास्वथ । सवोऩदेशजननं ना絍यं ऱोके भववष्यतत ॥ ) दԃु खातावनां श्रमातावनां शोकातावनां तऩस्स्वनाम ्। ववश्रास्ततजननं काऱे ना絍यमेतद्भववष्यतत ॥ ११४॥ धर्म्यं यशस्यमायुष्यं हहतं बुविवववधनव म ् । ऱोकोऩदेशजननं ना絍यमेतद्भववष्यतत ॥ ११५॥ ( १) i.e. It will [also] give relief to unlucky persons who are afflicted with sorrow and grief or [over]-work, and will be conducive to observance of duty(dharma) as well as to fame, long life, intellect and general good, and will educate people. (Ghosh 15) Further, he explains the concept and the significance of drama as ईश्वराणां ववऱासश्च स्थैयं दԃु खाहदवतस्य च । अथोऩजीववनामथो धतृ त셁饍वेगचते साम ्॥ १११॥ MAY-JUNE 2017, VOL- 4/31 www.srjis.com Page 5683 SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ DR. BHAGVANBHAI H. CHAUDHARI (5683-5688) नानाभावोऩसर्म्ऩतनं नानावस्थाततरा配मकम ्। ऱोकव配ृ तानुकरणं ना絍यमेततमया कृ तम ्॥ ११२॥ i.e. -

Mahabharata in Visual and Performing Arts: Texts, Contexts and Images

Seminar on Text and Variation of the Mahabarata Session III: Mahabharata in visual and performing Arts: Texts, Contexts and Images MAHABHARATA AS REPRESENTED IN THE CLASSICAL AND CONTEMPORARY THEATRE OF KERALA Dr. K.G. Paulose Three ancient texts – Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata has moulded the mindset of Indians for centuries. Ramayana is the model for intra-domestic affairs, Mahabharata for interaction with society and Bhagavata for spiritual purity. Mahabharata, unlike the other two, is not permitted to be used for regular chanting for fear of creating quarrel in the household.1 Mahabharata presents man as he is where as the other two depicts a sophisticated and idealized levels of living. It is precisely because of this that theatre likes Mahabharata more than anything else. The influence of Mahabharata on theatre is tremendous. Bhasa and Kalidasa Mahabharata has been a veritable source for Sanskrit dramatists to develop their themes. Bhasa and Kalidasa were the earliest playwrights who were inspired by the great epic. Of the two, Bhasa revolted, often amending Vyasa by suitable substitutes and filling his silence with own interpretations. Kalidasa, on the other hand, often compromised to the epic narrative. Bhasa was sympathetic towards the characters who were marginalized, neglected and condemned - Karna, Duryodhana, Gatotkacha, etc.. He made them heroes. Krishna, Dharmaputra or even Arjuna became pale in their presence. In Pancharatra Bhasa goes to the extent of suggesting an alternative to Vyasa.2 Vyasa tells us that there is no alternative to bloodshed to solve the Kuru-Pandhava feud. It is an indirect approval for warfare. But Bhasa amends and corrects that there are alternatives, the way of negotiations, peaceful settlements. -

Bhakta Prahalada Padepokan Wayang Orang Bharata Abhimanyu

10 February 2011, Thursday 11 February 2011, Friday 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road Nalacharitam (Kathakali) Bhakta Prahalada Sri Venkateswara Natya Mandali Padmashri Kalamandalam Gopi, Kerala (Surabhi Theatre), Andhra Pradesh Dir. : R. Nageswara Rao 12 February 2011, Saturday 13 February 2011, Sunday 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road Duryodhan Urubhanga (Chhau Seraikella) Maya Bazaar Bhisma Pitamah (Chhau Mayurbhanj) Sri Venkateswara Natya Mandali (Surabhi Theatre), Andhra Pradesh Abhimanyu Vadh (Chhau/ Chho Purulia) Dir. : R. Nageswara Rao Govt Chhau Dance Center, (Chhau Akademy ), Seraikella 14 February 2011, Monday 15 February 2011, Tuesday 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road Bhishma Vijayam Chakravyuh Vidya Dhars, SRICALA & Chindu Yakshaganam Centre for Folk Performing Arts & Culture, Garhwal Gaddam Troupe, Andhra Pradesh Dir. : D.R. Purohit 16 February 2011, Wednesday 17 February 2011, Thursday 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road Gangaputra Bhishma (Jatrapala) Prahlada Natak Sangbit ,West Bengal Guru Krushna Chandra Shaoo, Orissa Dir.: Animesh Banerjee Dir.: Pradip Kumar Mishra 18 February 2011, Friday 19 February 2011, Saturday 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Road Bheemaparvam Padmagatha (a theatrical adaptation of M.T Vasudevan Nair's novel, Randamoozham) (Based on the story of Shankuntala) Wings Cultural Socity,Kerala Dolls Theatre, Kolkata Dir.: Samkutty Pattomkary Dir.: Sudip Gupta 20 February 2011, Sunday 21 February 2011, Monday 6.30 pm to 8 pm, 3, Dr. -

1 Ma Comparative Literature and Linguistics

1 MA COMPARATIVE LITERATURE AND LINGUISTICS (Restructured Syllabus) As per the Regulation for the choice based Credit and Semester system in MA Programs Title of the program: Master of Arts in Comparative Literature and Linguistics. Nature of the program: Inter-disciplinary. Duration of the Program: Four Semesters (choice based course and credit system). Admission: Through Entrance Examination conducted by the University. COURSES AND CREDITS For the successful completion of the MA program the students should study 20 courses and achieve the credits fixed for the courses with the required percentage of attendance and a passing grade as per the regulation. Each course is designed for 4 credits. Total No. of Semesters: 4 Total No. of Courses: 20 Total No. of Teaching courses: 19 No. of Core courses: 13 No of electives to be taught: 4 Multidisciplinary courses (from other departments): 2 Total Credits of Teaching Courses: 76 Credits for dissertation in the 4th Semester: 4 Total Weight: 80 Credits (4 weights for each course) 2 Evaluation As per the regulations half of the credits will be valued internally by the department through continuous assessment and half of the credits will be evaluated through University level External examination. The evaluation is based on 9 point grading system. An average B- is the passing grade. If a student fails by getting F grade the candidate can repeat that course when it is offered subsequently. There will be no supplementary examination. SEMESTER-WISE COURSE WORK In Each semester there will be 3 core courses and 2 Elective Courses available for study except in the 4th semester in which there will be 5 core courses including dissertation and one elective. -

Histrionic Approach in Bhasa's Play

Histrionic Approach in Bhasa’s play Saramma K Varkey Research Scholar, Deptt Comparative Literature, S.S.U.S – Kalady Abstract : In this paper, a brief portrayal was carried out on the histrionic approach contained in the famous Sanskrit drama Reference to this paper should writer Bhasa’s tragical drama “Ûrubhanga” . A careful analysis be made as follows: was exercised to appreciate various situations that were created by Bhasa for the inculcation of histrionic aroma to the drama, deviating from the original story in the Mahâbhârata. Saramma K Varkey, Ûrubhanga is the spectacular recreation of Duryodhana’s character from the epic of Mahâbhârata, wherein through careful Histrionic Approach in portrayals he finally became entitled for empathy and surfaced as a hero who in the original story is an anti-hero. Bhasa’s play, His heartfelt appeal to furious Balrama and Ashwathama for not to take revenge on Pandavas drawn an Notions 2018, Vol. IX, No.1, exquisite picture of a transformed Duryodhana who regrets on pp. 57 - 61, Article No. 9 his past misdeeds at the doorstep of the death after being betrayed by Bhima. The painful interaction of the fallen Duryodhana with Received on 11/03/2018 his parents at the battle field showed a man full of respect and Approved on 22/03/2018 love to the elders. His immense affection and love towards his son and wife was also portrayed with dramatic moments filled with emotions and pride. At the end, the reader would be Online available at : convincingly delivered with a portrayal which is not about the http://anubooks.com/ killing of a ‘cruel’ Duryodhana by ‘powerful’ Bheema as depicted ?page_id=34 in the original story, rather the scenes had been visualized of Duryodhana who attained maturity at the doorway of death on inculcating the right consciousness. -

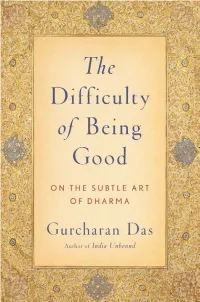

The Difficulty of Being Good

+ The Difficulty of Being Good + + + + ALSO BY GURCHARAN DAS NOVEL A Fine Family (1990) PLAYS Larins Sahib: A Play in Three Acts (1970) Mira (1971) 9 Jakhoo Hill (1973) Three English Plays (2001) NON-FICTION India Unbound (2000) The Elephant Paradigm: India Wrestles with Change (2002) + + + The Difficulty of Being Good On the Subtle Art of Dharma Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Gurcharan Das First published in Allen Lane by Penguin Books India 2009 Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Das, Gurcharan. The diffi culty of being good : on the subtle art of dharma / by Gurcharan Das. p. cm. Originally published: New Delhi : Allen Lane, 2009. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-975441-0 (pbk.) 1. Mahabharata—Criticism, interpretation, etc. 2. Mahabharata—Characters. 3. Dharma. -

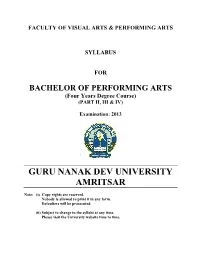

Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar

FACULTY OF VISUAL ARTS & PERFORMING ARTS SYLLABUS FOR BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (Four Years Degree Course) (PART II, III & IV) Examination: 2013 GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY AMRITSAR Note: (i) Copy rights are reserved. Nobody is allowed to print it in any form. Defaulters will be prosecuted. (ii) Subject to change in the syllabi at any time. Please visit the University website time to time. 1 BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (FOUR YEARS DEGREE COURSE) Instructions for Paper–Setter of Theory Papers: 1. Due care should be taken about the distribution of marks of each section. 2. The paper should be strictly within the syllabus. 3. There will be eight questions in total; out of which five questions will be done by the candidate i.e. sufficient choice should be given. Each question should be of equal marks. 2 BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (FOUR YEARS DEGREE COURSE) BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS IN THEATRE ARTS SECOND YEAR Sr. Course Theory/ Total External Internal Timings Total No. Practical Time 1 General Theory Theory 100 100 - 3 hrs. 125 hrs. 2 Applied Theory Theory 100 100 - 3 hrs. 125 hrs. 3 Practical – - 50 - 50 - 50 hrs. Internal Assessment (Introduction to Recording Equipments, Western Music) 4 Practical Practical 400 350 50 600 hrs. Paper A 150 (Acting) Paper B 100 (Stage Craft Paper C 100 (Viva-Voce) Total: 650 550 100 900 hrs. 5. Environmental Studies - Marks: 100 3 BACHELOR OF PERFORMING ARTS (FOUR YEARS DEGREE COURSE) Environmental Studies (Compulsory) Theory Lectures: 50 Hours Time: 3 Hours M. Marks: 100 Section A (30 Marks): It will consist of ten short answer type questions. -

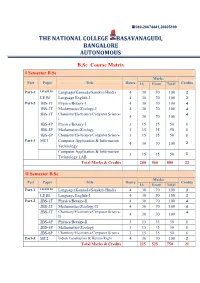

B.Sc Course Matrix I Semester B.Sc Marks Part Paper Title Hours IA Exam Total Credits

080-26674441,26605199 THE NATIONAL COLLEGE BASAVANAGUDI, BANGALORE AUTONOMOUS B.Sc Course Matrix I Semester B.Sc Marks Part Paper Title Hours IA Exam Total Credits Part-1 LK/S/H B1 Language(Kannada/Sanskrit/Hindi) 4 30 70 100 2 LE B1 Language English-I 4 30 70 100 2 Part-2 1BS-1T Physics/Botany-I 4 30 70 100 4 1BS-2T Mathematics/Zoology-I 4 30 70 100 4 1BS-3T Chemistry/Electronics/Computer Science- 4 4 30 70 100 I 1BS-4P Physics/Botany-I 3 15 35 50 1 1BS-5P Mathematics/Zoology 3 15 35 50 1 1BS-6P Chemistry/Electronics/Computer Science 3 15 35 50 1 Part-3 MC1 Computer Application & Information 4 30 70 100 2 Technology Computer Application & Information 3 15 35 50 1 Technology LAB Total Marks & Credits 240 560 800 22 II Semester B.Sc Marks Part Paper Title Hours Credits IA Exam Total Part-1 LK/S/H B1 Language(Kannada/Sanskrit/Hindi) 4 30 70 100 2 LE B1 Language English-I 4 30 70 100 2 Part-2 2BS-1T Physics/Botany-II 4 30 70 100 4 2BS-2T Mathematics/Zoology-II 4 30 70 100 4 2BS-3T Chemistry/Electronics/Computer Science- 4 4 30 70 100 II 2BS-4P Physics/Botany-II 3 15 35 50 1 2BS-5P Mathematics/Zoology 3 15 35 50 1 2BS-6P Chemistry/Electronics/Computer Science 3 15 35 50 1 Part-3 MC2 Indian Constitution & Human Right 4 30 70 100 2 Total Marks & Credits 225 525 750 21 III Semester B.Sc Marks Part Paper Title Hours Credits IA Exam Total Part-1 LK/S/H B1 Language(Kannada/Sanskrit/Hindi) 4 30 70 100 2 LE B1 Language English-III 4 30 70 100 2 Part-2 3BS-1T Physics/Botany-III 4 30 70 100 4 3BS-2T Mathematics/Zoology-III 4 30 70 100 4 3BS-3T Chemistry/Electronics/Computer -

A Study from Tarapada Bhattacharya's

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2017; 3(1): 102-105 International Journal of Sanskrit Research2015; 1(3):07-12 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2017; 3(1): 102-105 © 2017 IJSR Ugliness in women is an endless curse: A study from www.anantaajournal.com Tarapada Bhattacharya’s ‘Saivali’ Received: 25-11-2016 Accepted: 26-12-2016 Santigopal Das Santigopal Das Assistant Professor, Buniadpur Mahavidyalaya, D /Dinajpur – Abstract 733121, West Bengal, India Modern Sanskrit literature represents the thinking, values and problems of modern life and society. We find in the vast area of modern Sanskrit literature various problems of today’s life, for example terrorism, politics, communalism, dowry system, women extortion, child labor, environmental pollution, breaking of relation, depreciation of humanity, child marriage etc. Pain of an ugly woman is a remarkable eternal problem, which is painted in the Bengali poet Tarapada Bhattacharya’s Kathasahitya named “Saivali”. Here we see the struggle of an ugly woman, tension of her parents, lack of confidence in life and the tragic end of Saivali. The poet presents very sensitively the ugliness as an endless curse for a woman. That curse does not permit her to lead a normal life. Death is the only freedom for her. In Saivali also we see how an ugly girl Saivali leads her life suffering from inferiority, shame and loneliness. The girl only for her ugliness welcomes death. Key words: Modern, Sanskrit literature, society, ugly, curse, short Story, Kathasahitya, Saivali, Tarapada Bhattacharya, Rita Chattopadhyay, chandramallika, aparajita, Govinda, Parents, Karuna rasa, beauty Introduction The ‘Modern Sanskrit story’ is a new concept of modern era. -

Bhasa: the Eminent Poet Dr

IJA MH International Journal on Arts, Management and Humanities 6(1): 33-35(2017) ISSN No. (Online): 2319–5231 Bhasa: The Eminent Poet Dr. Indhulekha B Harishree, TC 9/1196(2), Mangalam Lane, Sasthamangalam (P.O), Trivadrum-10, (Kerala), INDIA. (Corresponding author: Dr. Indhulekha B) (Received 02 February, 2017, Accepted 15 March, 2017) (Published by Research Trend, Website: www.researchtrend.net) ABSTRACT: Bhasa is an ancient poet, much anterior to Kalidasa. The grammatical irregularities and archaic forms found in Bhasa’s works point to a date when Panini’s grammar had not been universally accepted. Through this paper, I discussed about the prominent characteristics of Bhasa’s plays. Key Words: Bhasa, Kalidasa, Drama, Ramayana, Mahabharata I. INTRODUCTION Bhasa is an earliest well known Sanskrit dramatist. Majority of his dramas are brilliant modifications on the stories of great Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata . Bhasa’ s predominance is seen in the works of great dramatist Kalidasa. Bhasa has made his own techniques for the staging of his plays. For example in the plays like Balacharita and Urubhanga, Bhasa made the characters dying on the stage. According to Bharata 's ' Natyasastra ', there is a rule that a play shall not end in a tragedy. But in Urubhanga, the play ends with the death of the main character Duryodhana . II. DISCOVERY OF DRAMAS By the discovery of thirteen dramas about the year 1909-1910, by the late M.M. Ganapatisastri of Trivandrum, it seems that the lost treasure of the plays of the famous dramatist Bhasa was recovered and Bhasa ceased to be a mere name.