H-Diplo Review Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Europeanising spaces in Paris, ca. 1947-1962 McDonnell, H.M. Publication date 2014 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): McDonnell, H. M. (2014). Europeanising spaces in Paris, ca. 1947-1962. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Conclusion ‘Notre héritage européen’, suggested Jorge Semprún in 2005, ‘n’a de signification vitale que si nous sommes capable d’en déduire un avenir.’1 Looking perpetually backwards and forwards was central to processes of making sense of Europe in Paris in the post-war period. Yet, for all the validity of Semprún’s maxim, it needs to be reconciled with Frederick Cooper’s critique of ‘doing history backwards’. -

A Powerful Political Platform: Françoise Giroud and L'express in a Cold War Climate Imogen Long Abstract Founded in 1953 by J

1 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in French History following peer review. The version of record, Imogen Long; A powerful political platform: Françoise Giroud and L’Express in a Cold War climate, French History, Volume 30, Issue 2, 1 June 2016, Pages 241–258, is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/fh/crw001. A powerful political platform: françoise giroud and l’express in a cold war climate Imogen Long Abstract Founded in 1953 by Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber and Françoise Giroud, L’Express was a politically committed outlet predominantly led by Giroud’s strong editorial direction until its rebranding in 1964 along the lines of Time magazine. Its goals were clear: to encourage modernization in French cultural and economic life, to support Pierre Mendès France and to oppose the war in Indochina. This article investigates Giroud’s vision of the press, her politics and her journalistic dialogue with other significant actors at a complex and pivotal juncture in French Cold War history. Giroud opened up the columns of L’Express to a diverse range of leading writers and intellectuals, even to those in disagreement with the publication, as the case study of Jean-Paul Sartre highlighted here shows. In so doing, Giroud’s L’Express constituted a singularly powerful press platform in Cold War France. I 2 For Kristin Ross, the “ideal couple”’ of Giroud and Servan-Schreiber at the helm of L’Express echoed the pairing of Sartre and Beauvoir; 1 yet Giroud and Servan-Schreiber were a duo with a different outlook, focused on economic development and the modernization of French society along American lines. -

The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1970 The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic Lorin James Anderson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Anderson, Lorin James, "The 1958 Good Offices Mission and Its Implications forr F ench-American Relations Under the Fourth Republic" (1970). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1468. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1467 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THBSIS Ol~ Lorin J'ames Anderson for the Master of Arts in History presented November 30, 1970. Title: The 1958 Good Offices Mission and its Implica tions for French-American Relations Under the Fourth Hepublic. APPROVED BY MEHllERS O~' THE THESIS CO.MNITTEE: Bernard Burke In both a general review of Franco-American re lations and in a more specific discussion of the Anglo American good offices mission to France in 1958, this thesis has attempted first, to analyze the foreign policies of France and the Uni.ted sta.tes which devel oped from the impact of the Second World Wa.r and, second, to describe Franco-American discord as primar ily a collision of foreign policy goals--or, even farther, as a basic collision in the national attitudes that shaped those goals--rather than as a result either of Communist harassment or of the clash of personalities. -

Political Leadership in France: from Charles De Gaulle to Nicolas Sarkozy

Political Leadership In France: From Charles De Gaulle To Nicolas Sarkozy John Gaffney Total number of pages (including bibliography): 440 To the memory of my mother and father ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements List of abbreviations Introduction Chapter 1: 1958: The Gaullist Settlement and French Politics The Elements of the New Republic in 1958 The Birth of the New Republic Understanding the New Republic The Characteristics of the New Republic Chapter 2: 1958-1968: The Consolidation and Evolution of the Fifth Republic The 1962 Referendum and Elections Gaullism and the Gaullists De Gaulle on the World Stage Left Opposition The New Conditions of the Republic Gaullism and Government De Gaulle The Left 1965-1967 Chapter 3: 1968 and its Aftermath Sous les Pavés, la Cinquième République ‘Opinion’ The unmediated relationship escapes to the streets Personal Leadership (and its rejection) iii Chapter 4: 1969-1974: Gaullism Without de Gaulle The 1969 Referendum The 1969 Presidential Election The Pompidou Presidency: 1969-1974 Pompidou and the Institutions Pompidou and Foreign Affairs Left Opposition, 1969-1974 Chapter 5: 1974-1981: The Giscard Years The 1974 Elections Slowing Down the ‘Marseillaise’ Then Speeding It Up Again Giscard and his Presidency Gaullism and Giscardianism The Left 1978-1981 Chapter 6: 1981-1988: From the République Sociale to the République Française The 1981 Elections The 1986 Election 1986-1988 Chapter 7: 1988-2002: The Long Decade of Vindictiveness, Miscalculations, Defeat, Farce, Good Luck, Good Government, and Catastrophe. The Presidency Right or Wrong. 1988-1993: System Dysfunction and Occasional Chaos Rocard Cresson Bérégovoy 1993-1995: Balladur. Almost President 1995-1997: Balladur out, Chirac in; Jospin up, Chirac down: Politics as Farce 1997-2002: The Eternal Cohabitation. -

Socialists and Europe 19Th-20Th Centuries

Political models to make Europe (since modern era) Socialists and Europe 19th-20th centuries Fabien CONORD ABSTRACT For socialists, Europe was both an area for political practices as well as an ideological horizon. The road of exile and international congresses made the continent into a lived space. This territory was later conceived of as a political place, however European integration deeply divided socialists, even if a number of their leaders were prominent figures in the construction of Europe. Parties from the north were especially reluctant to join the community, seen as being too neo-liberal. Members of the Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament protest austerity measures at the parc du Cinquantenaire in Brussels, Belgium on September 29, 2010. Like other political families, socialists had to take a position on the construction of a unified Europe beginning in the mid-twentieth century. The originality of this movement was the fact that beginning in the nineteenth century, the continent for socialists was an area of political practices as much as it was an ideological horizon. A Lived Space One of the characteristics of the socialist political family as it was structured in the nineteenth century was its transnational dimension, expressed in the slogan “Workers of the world, unite!” Socialists formed a number of successive Internationals that until the 1980s were essentially European clubs, despite their global ambitions. The International Socialist Bureau was for a long time headquartered in Brussels, serving as a kind of European capital of socialism at the beginning of the twentieth century. As well as the intellectual circulation generated through the organization of regular international congresses, the European experience of socialists involved militant paths often travelled while in exile. -

Trading Places: America and Europe in the Middle East

Trading Places: America and Europe in the Middle East Philip H. Gordon See if this story sounds familiar. A Western Great Power, long responsible for security in the Middle East, gets increasingly impatient with the hard- line position taken by nationalist leaders in Iran. Decades of historical baggage weigh heavily on both sides, and the Iranians deeply resent the way the Great Power had supported its corrupt former leaders and exer- cised influence over their internal affairs. In turn, the Great Power resents the challenge to its global leadership posed by the Tehran regime and begins to prepare plans for the use of military force. With the main protagonists refusing all direct diplomatic contact and heading toward a confrontation, the Great Power’s nervous allies dispatch negotiators to Tehran to try to defuse the dispute and offer a compromise. The Great Power denounces the compromise as appeasement and dusts off the military plans. The West is deeply split on how to handle yet another challenge in the Persian Gulf and a major showdown looms. The time and place? No, not America, Iran and Europe today, but the 1951 clash between the United Kingdom and the Mohammad Mosaddeq regime in Iran, with the United States in the role of mediator. In 1951, the issue at hand was not an incipient Iranian nuclear programme but Mosaddeq’s plan to nationalise the Iranian oil industry. The Truman administration, sympathetic to Iran’s claim that it deserved more control over its own resources, feared that Britain’s hard line would push Iran in an even more anti-Western direction and worried about an intra-Western crisis at a time when a common enemy required unity. -

Entretien Avec Pierre Mauroy Par Thibault Tellier Fiche Chrono-Thématique

Entretien avec Pierre Mauroy par Thibault Tellier Fiche chrono-thématique Dates Titre Thèmes Descripteurs/ Mots-clef Repères de recherche Correspondance entretien Les réflexions sur la À la SFIO : Jacobins/ girondins Michel ROCARD 00'00'00 - 00'09'35 décentralisation à la fin la place de Pierre Mauroy et diversité des Etatisme Jean-Pierre CHEVENEMENT des années 60 dans les positionnements Jeunesses socialistes PSU mouvements de gauche autogestion et décentralisation Gaston DEFERRE description des gauches Lille François MITTERRAND 1973 La décentralisation du Rapports avec les préfets: 00'09'35 - 00'12'15 point de vue de la mairie l'Equipement, bras armé des préfets de Lille Position de Pierre Mauroy dans la SFIO CEDEP Guy MOLLET 00'12'15 - 00'17'57 Fédération Léo Lagrange M. SCHMIDT M. CAZELLES M. DARRAS Daniel MAYER Tensions avec l'Etat : Le congrès d'Epinay-sur- 00'17'57 - 00'22'42 la montée de François Mitterrand et le Seine rapprochement avec Pierre Mauroy Centralisme politique et décentralisation territoriale Le rôle de maire : Conseil de quartier 00'22'42 - 00'24'36 déconcentration et intercommunalité rénovation Exemple de la politique de rénovation Préfet Jacques CHABAN-DELMAS 00'24'36 - 00'29'12 urbaine de Lille : André CHADEAU relations avec les acteurs de l'aménagement du territoire DDE centralisatrice Décentralisation, Pierre Mauroy, 29 mai 2009, 02_03_05 1 Les opposants à la décentralisation : Force Ouvrière ATOS 00'29'12 - 00'34'39 DDE centralisatrice : la tutelle des communes CFDT syndicats CGT La procédure « Habitat et vie -

AJC Memorandum on the Current Situation in Algeria

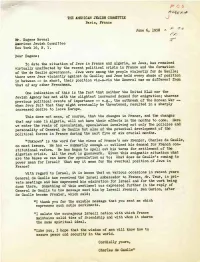

THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE Paris> France June 6, 1958 * ^ Mr. Eugene Hevesi Cf** American Jewish Committee New York 16, N. Y. Dear Eugenes To date the situation of Jews in France and Algeria, as Jews, has remained virtually unaffected by the recent political crisis in France and the formation of the de Gaulle government. Jews were among the people violently for de Gaullej there were Jews violently against de Gaullej and Jews held every shade of position in between — in short, their position vis-a-vis the General was no different from that of any other Frenchman* One indication of this is the fact that neither the United HIAS nor the Jewish Agency has met with the slightest increased demand for emigration} whereas previous political events of importance — e.g., the outbreak of the Korean War — when Jews felt that they might eventually be threatened, resulted in a sharply increased desire to leave Europe. This does not mean, of course, that the changes in France, and the changes that may come in Algeria, will not have their effects in the months to come. Here we enter the realm of speculation, speculation involving not only the policies and personality of General de Gaulle but also of the potential development of the political forces in France during the next five or six crucial months. "Unknown" is the word for the views of France's new Premier, Charles de Gaulle, on most issues. He has — summarily enough — outlined his demand for French con- stitutional reform. He has begun to spell out his terms for settlement of the Algerian crisis. -

FAIRE L'europe SANS DÉFAIRE LA FRANCE Gérard Possuat

A 393106 FAIRE L'EUROPE SANS DÉFAIRE LA FRANCE 60 ANS DE POLITIQUE D'UNITÉ EUROPÉENNE DES GOUVERNEMENTS ET DES PRÉSIDENTS DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE (1943-2003) Gérard pOSSUAT Euroclion°30 Table des matières Liste des abréviations 13 PARTIE I L'ENGAGEMENT DE LA FRANCE Introduction Le désir d'unité 19 Chapitre 1 1944, la Libération, tout est possible 29 Chapitre 2 L'engagement de la IVe République (1955-1958) dans les traités de Rome 57 Chapitre 3 L'Europe européenne du général de Gaulle 83 Chapitre 4 L'Europe pragmatique de Georges Pompidou 119 Chapitre 5 L'Europe confédérée des gouvernements avec Valéry Giscard d'Estaing : 141 Chapitre 6 François Mitterrand ou l'Europe-modèle 159 Chapitre 7 La Fédération européenne des États-nations de Jacques Chirac (1995-2003) 185 Conclusion Les Communautés européennes ont besoin de la France 213 PARTIE II TEXTES : LA PAROLE DES ACTEURS ET DES TÉMOINS Table des textes 223 1 - Entretien Spaak-Dejean (6 mars 1942) 227 2 - Monnet et l'entité européenne (août 1943) 230 8 Faire l'Europe sans défaire la France 3 - Un ensemble fédéral occidental : note de René Mayer (septembre 1943) 233 4 - Le CFLN prépare une réponse (octobre 1943) 238 5 - Projets d'organisation économique européenne (mars 1944) 241 6 - Entretien du général de Gaulle au Times (septembre 1945) 243 7 - Churchill à Zurich (septembre 1946) 247 8- Un dictateur du charbon de la Ruhr en 1945 251 9 - Coordonner la production de charbon allemand 253 10 - Production du charbon de la Sarre et de la Ruhr 255 . 11 - Une autre politique allemande de la France en 1946 ? 257 12 - Les États-Unis encouragent l'union de l'Europe occidentale 261 13 - L'union de l'Europe : une des conditions de l'aide américaine 263 14 - Lettre d'Henri Bonnet à Vincent Auriol président de la République française (mai 1948) 266 15 -La France n'inspire pas confiance à l'Angleterre 269 16 - M. -

North Africa Cfg-1-15? American Universities

NORTH AFRICA CFG-1-15? AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES 522 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK 36.NY NORTH AFRICA: 1956 A Summary of the Year's Events in North Africa A Report from Charles F. Gallagher New Pork January 10, 1957 The year 1956 was a turning point in the history of North Africa, and future historians may look upon it as the most important year since the French landings in Algiers in 1830. In a year studded with such momentous events as the Suez and Hungarian crises, the events in North Africa, with the beginnings of the end of a 125-year- long French colonial domination, rank perhaps in third place among the vital happenings of the year in foreign affairs. The year began with only Libya, among the four states of the area, an independent nation; it closed with three of the four self-governing. More concisely, it started with one person in 25 self-ruled; it ended with 15 of every 25 free. It saw the creation of two new nations: Morocco a arch 2), and Tunisia a arch 20), and witnessed their admission to the United Nations and many of its specialized agencies as full-fledged and respected members of the international community. It was a year in which the promises for a better future augured in 1955 were fulfilled in many ways, but one in which the economic and social difficulties attending a coming- of-age were brought into relief toward the close. More than anything it was a year in the fields of social and educational reforms and justice where heartening steps forward were taken. -

De Gaulle and Europe

De Gaulle and Europe: Historical Revision and Social Science Theory by Andrew Moravcsik• Harvard University Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper Series 8.5 Abstract The thousands of books and articles on Charles de Gaulle's policy toward European integration, wheth er written by historians, social scientists, or commentators, universally accord primary explanatory importance to the General's distinctive geopolitical ideology. In explaining his motivations, only sec ondary significance, if any at all, is attached to commercial considerations. This paper seeks to re· verse this historiographical consensus by examining the four major decisions toward European integra tion during de Gaulle's presidency: the decisions to remain in the Common Market in 1958, to propose the Foucher Plan in the early 1960s, to veto British accession to the EC, and to provoke the "empty chair" crisis in 1965-1966, resulting in the "Luxembourg Compromise." In each case, the overwhelm ing bulk of the primary evidence-speeches, memoirs, or government documents-suggests that de Gaulle's primary motivation was economic, not geopolitical or ideological. Like his predecessors and successors, de Gaulle sought to promote French industry and agriculture by establishing protected mar kets for their export products. This empirical finding has three broader implications: (1) For those in· teresred in the European Union, it suggests that regional integration has been driven primarily by economic, not geopolitical considerations--even in the "least likely" case. (2) For those interested in the role of ideas in foreign policy, it suggests that strong interest groups in a democracy limit the im· pact of a leader's geopolitical ideology--even where the executive has very broad institutional autono my. -

June 17, 1993 Interview with André Finkelstein by Avner Cohen

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified June 17, 1993 Interview with André Finkelstein by Avner Cohen Citation: “Interview with André Finkelstein by Avner Cohen,” June 17, 1993, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, From the personal collection of Avner Cohen. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113997 Summary: Transcript of Avner Cohen's 1993 interview with André Finkelstein. Finkelstein, deputy director of the IAEA and a ranking official within the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), discusses Franco- Israeli nuclear technology exchange and collaboration in this 1993 interview. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation and Carnegie Corporation of New York (CCNY). Original Language: English Contents: English Transcription Interview with Dr. André Finkelstein [1] This interview was conducted on 17 June 1993 in Paris, France. Interviewer: Dr. Avner Cohen Dr. André Finkelstein: I was trained as a physical chemist, I spent two years in Rochester University in New York and then I came back and joined the French Commission.[2],[3] Dr. Avner Cohen: When was that? Finkelstein: ’53. And I was involved in isotope tritium production and then quickly the Commission was expanding very quickly, so many people had no chance to stay in the lab very long and I was called to headquarters and I was in international affairs. I float[ed] for many years in [International Atomic Energy Agency] IAEA[4] in Vienna and I was for four years as deputy director general in Vienna and then I came back . Cohen: For Hans Blix?[5] Finkelstein: Before Hans Blix, with [Sigvard] Eklund [6] in the Department of Research and Isotopes.