Pueblo County Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TESTIMONY of RANDY MOORE, REGIONAL FORESTER PACIFIC SOUTHWEST REGION UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of AGRICULTURE—FOREST SERVICE BE

TESTIMONY of RANDY MOORE, REGIONAL FORESTER PACIFIC SOUTHWEST REGION UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE—FOREST SERVICE BEFORE THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND REFORM—SUBCOMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENT August 20, 2019 Concerning WILDFIRE RESPONSE AND RECOVERY EFFORTS IN CALIFORNIA Chairman Rouda, Ranking Member and Members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to appear before you today to discuss wildfire response and recovery efforts in California. My testimony today will focus on the 2017-2018 fire seasons, as well as the forecasted 2019 wildfire activity this summer and fall. I will also provide an overview of the Forest Service’s wildfire mitigation strategies, including ways the Forest Service is working with its many partners to improve forest conditions and help communities prepare for wildfire. 2017 AND 2018 WILDIRES AND RELATED RECOVERY EFFORTS In the past two years, California has experienced the deadliest and most destructive wildfires in its recorded history. More than 17,000 wildfires burned over three million acres across all land ownerships, which is almost three percent of California’s land mass. These fires tragically killed 146 people, burned down tens of thousands of homes and businesses and destroyed billions of dollars of property and infrastructure. In California alone, the Forest Service spent $860 million on fire suppression in 2017 and 2018. In 2017, wind-driven fires in Napa and neighboring counties in Northern California tragically claimed more than 40 lives, burned over 245,000 acres, destroyed approximately 8,900 structures and had over 11,000 firefighters assigned. In Southern California, the Thomas Fire burned over 280,000 acres, destroying over 1,000 structures and forced approximately 100,000 people to evacuate. -

Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019

REVIEW OF CALIFORNIA WILDFIRE EVACUATIONS FROM 2017 TO 2019 STEPHEN WONG, JACQUELYN BROADER, AND SUSAN SHAHEEN, PH.D. MARCH 2020 DOI: 10.7922/G2WW7FVK DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R Wong, Broader, Shaheen 2 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. UC-ITS-2019-19-b N/A N/A 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Review of California Wildfire Evacuations from 2017 to 2019 March 2020 6. Performing Organization Code ITS-Berkeley 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report Stephen D. Wong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3638-3651), No. Jacquelyn C. Broader (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3269-955X), N/A Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3350-856X) 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. Institute of Transportation Studies, Berkeley N/A 109 McLaughlin Hall, MC1720 11. Contract or Grant No. Berkeley, CA 94720-1720 UC-ITS-2019-19 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period The University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Covered www.ucits.org Final Report 14. Sponsoring Agency Code UC ITS 15. Supplementary Notes DOI: 10.7922/G29G5K2R 16. Abstract Between 2017 and 2019, California experienced a series of devastating wildfires that together led over one million people to be ordered to evacuate. Due to the speed of many of these wildfires, residents across California found themselves in challenging evacuation situations, often at night and with little time to escape. These evacuations placed considerable stress on public resources and infrastructure for both transportation and sheltering. -

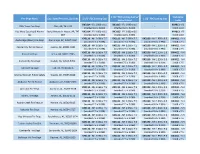

Fire Dept Name City, State/Province, Zip Code 2 1/2" FDC Locking Cap 2

2 1/2" FDC Locking Cap w/ Standpipe Fire Dept Name City, State/Province, Zip Code 2 1/2" FDC Locking Cap 1 1/2" FDC Locking Cap Swivel Guard Locks KX3114 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX3115 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX4013 - FD Olds Town Fire Dept Olds, AB, T4H 1R5 - (marked 8.0 x 3.000) (marked 8.0 x 3.000) 3.000 x 8.0 Key West Security & Alarms Rocky Mountain House, AB, T4T KX3114 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX3115 - FD 3.000 x 8.0 KX4013 - FD - Inc 1B7 (marked 8.0 x 3.000) (marked 8.0 x 3.000) 3.000 x 8.0 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Anchorage (Muni) Fire Dept Anchorage, AK, 99507-1554 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Capital City Fire & Rescue Juneau, AK, 99801-1845 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Kenai Fire Dept Kenai, AK, 99611-7745 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Kodiak City Fire Dept Kodiak, AK, 99615-6352 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH 1.990 x 9.0 KX4011 - NH Tok Vol Fire Dept Tok, AK, 99780-0076 (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 7.5 x 3.068) (marked 9.0 x 1.990) 3.068 x 7.5 KX3110 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3111 - NH 3.068 x 7.5 KX3190 - NH -

General Improvement Fund Grant Awards Fiscal Years 2008 - 2019 COUNTY APPLICANT PROGRAM AMOUNT STATUS CYCLE NARRATIVE Arkansas

General Improvement Fund Grant Awards Fiscal Years 2008 - 2019 COUNTY APPLICANT PROGRAM AMOUNT STATUS CYCLE NARRATIVE Arkansas Arkansas County Community Enhancement $17,000.00 Closed Out Arkansas County received $17,000.00 to renovate one of the facility buildings with steps and a landing Dewitt Community Enhancement $9,000.00 Active The City of Dewitt received $9,000 to renovate a recently donated office building into the City Hall. DeWitt Community Enhancement $18,000.00 Closed Out The City of DeWitt received $18,000 to repave the DeWitt Hospital and Nursing Home parking lot. Gillett Community Enhancement $20,000.00 Closed Out The Gillett Police Department received $20,000 to purchase updated computers and programming. Gillett Community Enhancement $9,500.00 Closed Out City of Gillett received $9,500 to purchase a new backhoe for the Public Works Department. Humphrey Fire Protection $7,548.00 Closed Out The Humphrey FD received $7,548 to purchase turnouts. Humphrey Fire Protection $2,500.00 Closed Out The Humphrey Volunteer Fire Dept received $2,500 to purchase new dump tank, foam concentrate, hose clamp, and other equipment. Humphrey Fire Protection $20,000.00 Active The Humphrey Fire Department received $20,000 to purchase turnout/bunker gear. St. Charles Fire Protection $30,000.00 Closed Out The St. Francis FD received $30,000 to expand their currnet fire station. Stuttgart Fire Protection $25,000.00 Closed Out The Stuttgart FD received $25,000 to create a training site for the surrounding fire departments. Stuttgart Community Enhancement $25,000.00 Closed Out The City of Stuttgart received $25,000 on behalf of the Holman Community Center to repair the roof in the main building. -

LAST NAME FIRST NAME TEAM DONATIONS 1 Thorsteinson Scott Burien/North Highline Fire $50018.00 2 Robinson Scott Coeur D Alen

# LAST NAME FIRST NAME TEAM DONATIONS 1 Thorsteinson Scott Burien/North Highline Fire $50,018.00 2 Robinson Scott Coeur d alene $20,617.25 3 Brown Richard Boise Firefighters Local 149 $16,557.66 4 Woodland Tim Burien/North Highline Fire $16,106.10 5 Smith Justin Vancouver Fire Local 452 $14,763.50 6 Fox Marnie Boeing Fire $14,429.00 7 Bryan Damon Richland Fire Department $12,016.87 8 Butler Amber Keizer Fire Department $11,632.23 9 Mann Mike Longview Fire $10,570.00 10 Bawyn Gerard Skagit District 8 $10,525.00 11 Nelson Dan Seattle Fire-Team Tristan $10,400.58 12 Schmidt Brad Everett Fire $10,234.75 13 Stenstrom Jasper Graham Fire $10,155.00 14 Frazier Mark Central Mason $10,030.00 15 Kulbeck J.D. Great Falls Fire Rescue $7,286.00 16 Allen William Meridian Firefighters $6,760.00 17 Yencopal Robert Corvallis Fire Department $6,367.00 18 Mathews Keith Columbia River Fire & Rescue $6,181.00 19 Emerick Mike Richland Fire Department $6,145.88 20 Gilbert Derek Marion County Fire District # 1 $5,993.62 21 Niedner Carl Corvallis Fire Department $5,991.11 22 Paterniti Joseph Everett Fire $5,956.50 23 Kilgore Richard Tumwater Fire $5,849.79 24 Predmore Alan City of Buckley Fire Department $5,810.00 25 Taylor Mark Bend Fire & Rescue $5,808.23 26 Rickert Eric Bellevue Fire $5,790.00 27 Jensen Justin Burley Fire Department $5,687.00 28 Haviland Thomas Bethel Fire Department $5,610.00 29 Condon Ian Tumwater Fire $5,590.39 30 Gorham Corey Umatilla County Fire Dist. -

Understanding California Wildfire Evacuee Behavior and Joint Choice-Making

Understanding California Wildfire Evacuee Behavior and Joint Choice-Making A TSRC Working Paper May 2020 Stephen D. Wong Jacquelyn C. Broader Joan L. Walker, Ph.D. Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. Wong, Broader, Walker, Shaheen Understanding California Wildfire Evacuee Behavior and Joint Choice- Making WORKING PAPER Stephen D. Wong 1,2,3 Jacquelyn C. Broader 2,3 Joan L. Walker, Ph.D. 1,3 Susan A. Shaheen, Ph.D. 1,2,3 1 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering 2 Transportation Sustainability Research Center 3 Institute of Transportation Studies University of California, Berkeley Corresponding Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT For evacuations, people must make the critical decision to evacuate or stay followed by a multi- dimensional choice composed of concurrent decisions of their departure time, transportation mode, route, destination, and shelter type. These choices have important impacts on transportation response and evacuation outcomes. While extensive research has been conducted on hurricane evacuation behavior, little is known about wildfire evacuation behavior. To address this critical research gap, particularly related to joint choice-making in wildfires, we surveyed individuals impacted by the 2017 December Southern California Wildfires (n=226) and the 2018 Carr Wildfire (n=284). Using these data, we contribute to the literature in two key ways. First, we develop two simple binary choice models to evaluate and compare the factors that influence the decision to evacuate or stay. Mandatory evacuation orders and higher risk perceptions both increased evacuation likelihood. Individuals with children and with higher education were more likely to evacuate, while individuals with pets, homeowners, low-income households, long-term residents, and prior evacuees were less likely to evacuate. -

THE IMPACT of NATURAL DISASTERS on SCHOOL CLOSURE by Camille Poujaud

THE IMPACT OF NATURAL DISASTERS ON SCHOOL CLOSURE by Camille Poujaud A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Agricultural Economics West Lafayette, Indiana December 2019 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Maria I. Marshall Department of Agricultural Economics Dr. Bhagyashree Katare Department of Agricultural Economics Dr. Ariana Torres Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Dr. Alexis Annes Department of Sociology and Rural Studies and department of Modern Languages Approved by: Dr. Nicole J. Olynk Widmar 2 To my beloved family and friends. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful to Dr. Maria I. Marshall for being my academic advisor. Throughout my year and a half of study at Purdue University, she has given me tremendous guidance and encouragement. She always showed patience and always been very comprehensive in every situation. I am very thankful that I was able to become her student. I am very thankful to Dr. Alexis Annes, for the help he provided from the other side of the ocean. Thank you for being available and responsive during the process of writing the thesis. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Ariana Torres for being present and active. She has given me tremendous support in the realization of this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Bhagyashree Katare for her suggestions and comments. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................... -

TEAM NAME TOTAL TEAM FUNDRAISING 1 Seattle Fire-Team

# TEAM NAME TOTAL TEAM FUNDRAISING 1 Seattle Fire-Team Tristan $98,494.39 2 Burien/North Highline Fire $77,767.10 3 Richland Fire Department $61,634.69 4 Boise Firefighters Local 149 $59,387.55 5 Everett Fire $57,287.39 6 Corvallis Fire Department $37,178.14 7 Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue/Local 1660 $30,994.02 8 Boeing Fire $28,819.00 9 City of Buckley Fire Department $27,869.20 10 Bend Fire & Rescue $27,233.45 11 Central Pierce Fire and Rescue $25,779.21 12 Vancouver Fire Local 452 $25,627.68 13 Coeur d alene $24,977.25 14 Nampa Fire Dept $22,622.00 15 Cal Fire / SLO County Fire $22,073.22 16 Central Mat-Su Fire Department $21,543.66 17 Kent Firefighters Local 1747 $21,493.39 18 Kirkland Fire $21,023.95 19 Skagit District 8 $20,605.00 20 Tacoma Fire $20,556.65 21 Navy Region Northwest Fire & Emergency Services $19,781.56 22 Tukwila Firefighters Local 2088 $19,596.89 23 Graham Fire $19,175.00 24 South Whatcom Fire Authority $19,016.48 25 San Bernardino County Fire Department $18,329.62 26 Meridian Firefighters $18,267.22 27 La Pine Fire District $17,963.95 28 Team Texas $17,684.00 29 Local 2878 $17,319.35 30 Central Mason $17,098.05 31 Bellevue Fire $16,999.00 32 Templeton Fire Department $16,832.00 33 Spokane Valley Fire Department $16,459.64 34 Tumwater Fire $15,803.96 35 Great Falls Fire Rescue $15,740.00 36 Central Valley Fire District $15,657.00 37 Longview Fire $15,575.00 38 Caldwell Fire Department $15,277.95 39 Umatilla County Fire Dist. -

Team Name Total Team Fundraising # Team Members

# TEAM NAME TOTAL TEAM FUNDRAISING # TEAM MEMBERS PER CAPITA AMOUNT 1 Coeur d alene $24,977.25 4 $6,244.31 2 Tumwater Fire $15,803.96 3 $5,267.99 3 Skagit District 8 $20,605.00 4 $5,151.25 4 Keizer Fire Department $14,207.23 3 $4,735.74 5 Tesoro Anacortes Fire Department $4,655.00 1 $4,655.00 6 St. Helena City Fire Department $8,915.00 2 $4,457.50 7 Burien/North Highline Fire $77,767.10 18 $4,320.39 8 Longview Fire $15,575.00 4 $3,893.75 9 Burley Fire Department $9,905.00 3 $3,301.67 10 North Whatcom Fire & Rescue $3,220.00 1 $3,220.00 11 Vancouver Fire Local 452 $25,627.68 8 $3,203.46 12 Bethel Fire Department $6,195.00 2 $3,097.50 13 Kittitas Valley Fire & Rescue $6,165.00 2 $3,082.50 14 Fredericktown Community Fire $3,080.00 1 $3,080.00 15 Chico Fire Department $11,962.09 4 $2,990.52 16 Sedro-Wooley Fire Department $2,962.00 1 $2,962.00 17 Douglas Fire Department $2,930.00 1 $2,930.00 18 Richland Fire Department $61,634.69 22 $2,801.58 19 Cle Elum Fire Department $2,625.00 1 $2,625.00 20 Great Falls Fire Rescue $15,740.00 6 $2,623.33 21 Idaho National Laboratory Fire Department $7,564.00 3 $2,521.33 22 Vallejo Fire $2,425.00 1 $2,425.00 23 Valdez Fire Department $7,015.00 3 $2,338.33 24 Meridian Firefighters $18,267.22 8 $2,283.40 25 East Pierce Fire & Rescue $4,560.00 2 $2,280.00 26 Walla Walla Fire District #4 $6,805.00 3 $2,268.33 27 Camas Washougal Fire Department $2,267.00 1 $2,267.00 28 Bozeman Fire Local 613 $6,472.08 3 $2,157.36 29 Chugiak Fire Department $12,903.00 6 $2,150.50 30 Cody Volunteer Fire Department $10,698.77 5 $2,139.75 31 Sanford/Rye Fire Department $2,130.01 1 $2,130.01 32 Boise Firefighters Local 149 $59,387.55 28 $2,120.98 33 Tracy Fire Department $6,306.98 3 $2,102.33 34 St. -

Annual Report

RIVERSIDE COUNTY FIRE DEPARTMENT IN COOPERATION WITH CAL FIRE ANNUAL REPORT 2017 MISSION STATEMENT Riverside County Fire Department is a public safety agency dedicated to protecting life, property and the environment through professionalism, integrity and efficiency. I VISION STATEMENT Riverside County Fire Department is committed to exemplary service and will be a leader in Fire protection and emergency services through continuous improvement, innovation and the most efficient and responsible use of resources. II III TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission Statement County Fire Chief’s Message 2 Organizational Structure 4 Response Statistics 9 Administration 18 Air Program 24 Camp Program 28 Communications/Information Technology 32 Emergency Command Center 36 Emergency Medical Services 40 Law Enforcement/Hazard Reduction 44 Fleet Services 48 Health and Safety 50 Office of the Fire Marshal 54 Pre Fire Management 58 Public Affairs Bureau/Education 62 Service Center 66 Strategic Planning 70 Training 74 Volunteer Reserve Program 78 Retirements/In Memoriam 80 The Year in Pictures 82 Acknowledgements 94 IV MESSAGE FROM THE FIRE CHIEF CAL FIRE AND RIVERSIDE COUNTY FIRE CHIEF DANIEL R. TALBOT 2 It is with pride that my staff and I publish this report. I am indeed proud of our service-oriented Fire Department. The combination of the State, County and locally funded fire resources has created a truly integrated, cooperative and regional fire protection system. This system has the capacity to respond to 452 requests for service daily and the resiliency, due to our depth of resources, to simultaneously respond to major structure and wildland fires. In 2017, our Fire Department responded to 164,594 requests for service. -

Names and Their Locations on the Memorial Wall

NAMES AND THEIR LOCATIONS ON THE MEMORIAL WALL UPDATED APRIL 6, 2021 New York State Fallen Firefighters Memorial Roll of Honor Hobart A. Abbey Firefighter Forest View/Gang Mills Fire Department June 23, 1972 7 Top Charles W. Abrams Firefighter New York City Fire Department June 22, 1820 21 Bottom Raymond Abrams Ex-Chief Lynbrook Fire Department June 30, 1946 15 Top Theodore J. Abriel Acting Lieutenant Albany Fire Department February 19, 2007 20 Bottom Leslie G. Ackerly Firefighter Patchogue Fire Department May 17, 1948 15 Top William F. Acquaviva Deputy Chief Utica Fire Department January 15, 2001 6 Bottom Floyd L. Adel Firefighter Fulton Fire Department December 4, 1914 4 Top Elmer Adkins Lieutenant Rochester Fire Department June 3, 1962 12 Bottom Emanuel Adler Firefighter New York City Fire Department November 16, 1952 14 Top William J. Aeillo Firefighter New York City Fire Department March 30, 1923 6 Top John W. Agan Firefighter Syracuse Fire Department February 3, 1939 17 Top Joseph Agnello Lieutenant New York City Fire Department September 11, 2001 3 Top Brian G. Ahearn Lieutenant New York City Fire Department September 11, 2001 14 Bottom Joseph P. Ahearn Firefighter New York City Fire Department April 10, 1934 19 Top Duane F. Ahl Captain Rotterdam Fire Department January 18, 1988 11 Top William E. Akin, Jr. Fire Police Captain Ghent Volunteer Fire Company No. 1 October 19, 2010 12 Top Vincent J. Albanese Firefighter New York City Fire Department July 31, 2010 19 Bottom Joseph Albert Firefighter Haverstraw Fire Department January 8, 1906 20 Top Michael F. -

City of Glendale Hazard Mitigation Plan Available to the Public by Publishing the Plan Electronically on the City’S Websites

Local Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 1: Introduction City of Glendale, California City of Glendale Hazard Mitigati on Plan 2018 Local Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents City of Glendale, California Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION 1-1 Introduction 1-2 Why Develop a Local Hazard Mitigation Plan? 1-3 Who is covered by the Mitigation Plan? 1-3 Natural Hazard Land Use Policy in California 1-4 Support for Hazard Mitigation 1-6 Plan Methodology 1-6 Input from the Steering Committee 1-7 Stakeholder Interviews 1-7 State and Federal Guidelines and Requirements for Mitigation Plans 1-8 Hazard Specific Research 1-9 Public Workshops 1-9 How is the Plan Used? 1-9 Volume I: Mitigation Action Plan 1-10 Volume II: Hazard Specific Information 1-11 Volume III: Resources 1-12 SECTION 2: COMMUNITY PROFILE 2-1 Why Plan for Natural and Manmade Hazards in the City of Glendale? 2-2 History of Glendale 2-2 Geography and the Environment 2-3 Major Rivers 2-5 Climate 2-6 Rocks and Soil 2-6 Other Significant Geologic Features 2-7 Population and Demographics 2-10 Land and Development 2-13 Housing and Community Development 2-14 Employment and Industry 2-16 Transportation and Commuting Patterns 2-17 Extensive Transportation Network 2-18 SECTION 3: RISK ASSESSMENT 3-1 What is a Risk Assessment? 3-2 2018 i Local Hazard Mitigation Plan Table of Contents City of Glendale, California Federal Requirements for Risk Assessment 3-7 Critical Facilities and Infrastructure 3-8 Summary 3-9 SECTION 4: MULTI-HAZARD GOALS AND ACTION ITEMS 4-1 Mission 4-2 Goals 4-2 Action