Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ithacan, 1987-02-26

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1986-87 The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 2-26-1987 The thI acan, 1987-02-26 The thI acan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1986-87 Recommended Citation The thI acan, "The thI acan, 1987-02-26" (1987). The Ithacan, 1986-87. 17. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1986-87/17 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1986-87 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. -- . ---· -- Warhol dies ... C ommon ' s Ja~z. ... Track places 2nd ... page 5 page 9 page 16 0""'-. - lA-:!,, 1 -~~ - -...:i \' ' •' ,--.._ ... ,,,..,~·._ . .,. THE The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Issue 17 February 26, 1987 16 pages*Free Caller IC prof. injured reports in car accident bomb Emergency surgery needed threat BY PATRICK GRAHAM but his condition is improving. B\' JERIL \'N VELDOF An Ithaca College professor sus "He is doing fine," said Liz A bomb threat over a hall phone in tained a concussion and a severe neck Snyder, Snyder's daughter. "He is on Terrace 11 B resulted in a one-and-a wound which required an emergency the road to recovery." half-hour evacuation Saturday, Feb. trachiotomy following a two-car col According to the police report and 14, according to Ithaca College Safe lision at the college's 968 entrance last witnesses' accounts, Farrell was ty and Security . -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. -

Than a Meal: the Turkey in History, Myth

More Than a Meal Abigail at United Poultry Concerns’ Thanksgiving Party Saturday, November 22, 1997. Photo: Barbara Davidson, The Washington Times, 11/27/97 More Than a Meal The Turkey in History, Myth, Ritual, and Reality Karen Davis, Ph.D. Lantern Books New York A Division of Booklight Inc. Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright © Karen Davis, Ph.D. 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data For Boris, who “almost got to be The real turkey inside of me.” From Boris, by Terry Kleeman and Marie Gleason Anne Shirley, 16-year-old star of “Anne of Green Gables” (RKO-Radio) on Thanksgiving Day, 1934 Photo: Underwood & Underwood, © 1988 Underwood Photo Archives, Ltd., San Francisco Table of Contents 1 Acknowledgments . .9 Introduction: Milton, Doris, and Some “Turkeys” in Recent American History . .11 1. A History of Image Problems: The Turkey as a Mock Figure of Speech and Symbol of Failure . .17 2. The Turkey By Many Other Names: Confusing Nomenclature and Species Identification Surrounding the Native American Bird . .25 3. A True Original Native of America . .33 4. Our Token of Festive Joy . .51 5. Why Do We Hate This Celebrated Bird? . .73 6. Rituals of Spectacular Humiliation: An Attempt to Make a Pathetic Situation Seem Funny . .99 7 8 More Than a Meal 7. -

Last Fifteen Minutes

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced withwith permission ofof thethe copyright owner.owner. FurtherFurther reproductionreproduction prohibited without permission. permission. THE LAST FIFTEEN MINUTES by Lvdia Jane Morris submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master o f Fine Arts m Creative Writing Chair. -

Ljury Vot~S for Death in \Capano Trial Sentencing

News Mosaic Sports Magic Schoolbus makes UD graduate creates hog 'Delaware men's basketball its Newark debut heaven on roadside snags overtime win 99-91 A4 B3 BS • • Non-Profit Org. : ~Review Online U.S. Postage Paid ewark, DE www. review. udel. edu Permit No. 26 :Free 250 Student Center • University of Delaware • Newark, DE 19716 Friday Volume 125, Number 28 · · Januar~ 29, 1999 lJury vot~s for death in \Capano trial sentencing BY JOHN YOCCA detailed his previous charitable deeds for the "Sorry I broke the rules," referring to his Assistant Editorial Ed;tor city of Wilmington. infractions during his plea WILMINGTON - A six-man, six-woman Capano also spoke of how he has changed Capano's 76-year-old mother, Marguerite, ~ury decided they believe Thomas J. Capano personally since his incarceration. preceded his testimony and maintained her ~hould be put to death by lethal injection for the "I don't know me anymore," he said, while son's innocence. ·1996 murder of Anne Marie Fahey. expressing some remorse for what happened to "My soli is not a murderer," she said. "He is : In a 10-2 vote, the jury decided Thursday Fahey, who he was convicted of killing. But he not guilty of killing Anne Marie Fahey ... !light that Capano planned and carried out stopped short of admitting to the murder. please don't kill my son. Please spare my son Fahey' s murder, stuffed her in a cooler and "If I could trade places with Anne Marie, I for his family and for his daughters." :dumped her corpse into the Atlantic Ocean. -

1. Dear Scott/Dear Max: the Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, Eds

NOTES INTRODUCTION F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, "THE CULTURAL WORLD," AND THE LURE OF THE AMERICAN SCENE 1. Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, eds. John Kuehl and Jackson R. Bryer (New York: Scribner's, 1971),47. Hereafter cited as Dear Scott/Dear Max. Throughout this book, I preserve Fitzgerald's spelling, punctuation, and diacritical errors as preserved in the edited volumes of his correspondence. 2. F. Scott Fitzgerald, A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994),67. Hereafter cited as Life in Letters. 3. F. Scott Fitzgerald, F. Scott Fitzgerald on Authorship, eds. Matthew J. Bruccoli and Judith S. Baughman (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996),83. Hereafter cited as Fitzgerald on Authorship. 4. For a superb discussion of the voguish "difficulty" associated with the rise of modernist art, see Leonard Diepeveen, The Difficulties ofModernism (New York: Routledge, 2003),1-42. 5. There is a further irony that might be noted here: putting Joyce and Anderson on the same plane would soon be a good indicator of provin cialism. Fitzgerald could not have written this statement after his sojourn in France, and certainly not after encouraging his friend Ernest Hemingway's nasty parody, The Torrents of Spring (1926). Anderson may be one of the most notable casualties from the period of ambitious claimants, such as Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and William Faulkner, to a place within "the cultural world." 6. Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, tr. Susan Emanuel (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 142. 7. "The principle of differentiation is none other than the objective and subjective distance of enterprises of cultural production with respect to the market and to expressed or tacit demand, with producers' strate gies distributing themselves between two extremes that are never, in fact, attained-either total and cynical subordination to demand or absolute independence from the market and its exigencies" (ibid., 141-42). -

SECTION-II.Pdf

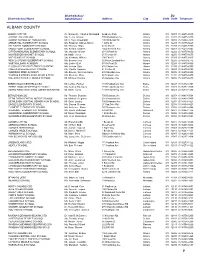

District/School Zip District/School Name Administrator Address City State Code Telephone ALBANY COUNTY ALBANY CITY SD Dr. Marguerite Vanden Wyngaard Academy Park Albany NY 12207 (518)475-6010 ALBANY HIGH SCHOOL Ms. Cecily Wilson 700 Washington Ave Albany NY 12203 (518)475-6200 ALBANY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Mr. C Fred Engelhardt 108 Whitehall Rd Albany NY 12209 (518)462-7258 ARBOR HILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Rosalind Gaines-Harrell 1 Arbor Dr Albany NY 12207 (518)475-6625 DELAWARE COMMUNITY SCHOOL Mr. Thomas Giglio 43 Bertha St Albany NY 12209 (518)475-6750 EAGLE POINT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Kendra Chaires 1044 Western Ave Albany NY 12203 (518)475-6825 GIFFEN MEMORIAL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Jasmine Brown 274 S Pearl St Albany NY 12202 (518)475-6650 MONTESSORI MAGNET SCHOOL Mr. Malik Jones 65 Tremont St Albany NY 12206 (518)475-6675 MYERS MIDDLE SCHOOL Ms. Kimberly Wilkins 100 Elbel Ct Albany NY 12209 (518)475-6425 NEW SCOTLAND ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Beverly Ivey 369 New Scotland Ave Albany NY 12208 (518)475-6775 NORTH ALBANY ACADEMY Ms. Lesley Buff 570 N Pearl St Albany NY 12204 (518)475-6800 P J SCHUYLER ACHIEVEMENT ACADEMY Ms. Jalinda Soto 676 Clinton Ave Albany NY 12206 (518)475-6700 PINE HILLS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Vibetta Sanders 41 N Allen St Albany NY 12203 (518)475-6725 SHERIDAN PREP ACADEMY Ms. Zuleika Sanchez-Gayle 400 Sheridan Ave Albany NY 12206 (518)475-6850 THOMAS S O'BRIEN ACAD OF SCI & TECH Ms. Shellette Pleat 94 Delaware Ave Albany NY 12202 (518)475-6875 WILLIAM S HACKETT MIDDLE SCHOOL Mr. -

White-Tailed Deer Management and Pine Savanna Restoration in the Southeastern Coastal Plain the Ichauway Approach

COASTAL PLAIN WHITETAILS White-tailed deer management and pine savanna restoration in the southeastern Coastal Plain The Ichauway Approach The intent of this publication is to provide information from our white-tailed deer management and monitoring programs, in the context of longleaf management and restoration at Ichauway. We have attempted to demonstrate how desirable deer herds can be maintained on properties managed with “non-traditional” white-tailed deer management objectives. It is our experience that managing for quality habitats can have a net-positive impact on white- tailed deer herds in the southeastern Coastal Plain. In making natural resource decisions, we encourage land owners and managers to consider multiple resource objectives and the promotion of quality habitats. It is also important to note that there is a wealth of information and technical assistance regarding habitat management available through state forest and wildlife management agencies, universities, and non-governmental organizations. In addition, we have taken the opportunity to present some information on the history and habitats of white-tailed deer in the Coastal Plain along with several emerging issues relative to deer management in the Southeast. Brandon T. Rutledge Conservation Wildlife Biologist Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center at Ichauway 1 White-tailed Deer in the Coastal Plain Historically, white-tailed deer were abundant and occupied most of the habitats present across the Coastal Plain of the southeastern United States, utilizing upland, bottomland, and coastal areas. Estimates of deer populations during this pre-settlement time period range from 10–100 deer per square mile. Deer were a vital resource for Native Americans providing an important source of food and materials for clothing and tools (McCabe and McCabe 1984). -

See the 2016 Report

Frameworks for Progress The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research 2016 Annual Report The Michael J. Fox Foundation Contents is dedicated to finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease through an 2 A Note from Michael aggressively funded research 3 An Update from the CEO and the Co-Founder 6 2016 in Photos agenda and to ensuring the 8 2016 Donor Listing development of improved 11 Planned Giving therapies for those living with 13 Industry Partners 18 Corporate and Matching Gifts Parkinson’s today. 28 Tributees 44 Recurring Gifts 46 Team Fox 58 2016 Financial Highlights 64 Credits 65 Boards and Councils 2016 Annual Report 3 The Michael J. Fox Foundation Contents is dedicated to finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease through an 2 A Note from Michael aggressively funded research 3 An Update from the CEO and the Co-Founder 6 2016 in Photos agenda and to ensuring the 8 2016 Donor Listing development of improved 11 Planned Giving therapies for those living with 13 Industry Partners 18 Corporate and Matching Gifts Parkinson’s today. 28 Tributees 44 Recurring Gifts 46 Team Fox 58 2016 Financial Highlights 64 Credits 65 Boards and Councils A Note from An Update from the CEO Michael and the Co-Founder Dear Friend, Each year, we are honored to share how your unflagging determination and sheer generosity have fortified our mission to do whatever it takes to drive research. As a Todd Sherer, PhD Deborah W. Brooks Chief Executive Officer Co-Founder and Executive year full of new endeavors and tremendous Vice Chairman growth, 2016 was no exception. -

Finding Birds in South Carolina

Finding Birds in South Carolina Finding Birds in South Carolina Robin M. Carter University of South Carolina Press Copyright © 1993 University of South Carolina Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carter, Robin M., 1945— Finding birds in South Carolina / Robin M. Carter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87249-837-9 (paperback : acid-free) 1. Bird watching—South Carolina—Guidebooks. 1. Title. QL684.S6C27 1993 598'.07234757—dc20 92-24400 Contents Part A—General Information A-1 An Introduction to Finding Birds in South Carolina 1 A-1.1 An Overview of the Natural Regions of South Carolina 1 A-1.2 An Overview of the Habitats for Birds in South Carolina 3 A-2 How to Use This Book 9 A-2.1 Organized by County 9 A-2.2 The Best Birding Areas in South Carolina by Season 10 A-2.3 Birding near Major Highways 11 A-3 Other Sources of Information 12 Part 8 — Site Information B-1 Abbeville County 14 B-1.1 Parsons Mountain, Sumter National Forest 14 B-1.2 Long Cane Natural Area, Sumter National Forest 15 B-1.3 Lowndesville Park on Lake Russell 16 13-2 Aiken County 16 B-2.1 Savannah River Bluffs Heritage Preserve 17 B-2.2 Aiken State Park and Vicinity 18 B-2.3 Hitchcock Woods in the Clty of Aiken 19 B-2.4 Beech Island to Silver Bluff 20 B-3 Allendale County 22 B-3.1 A Savannah River Tour (North of US 301) 22 B-3.2 A Savannah River Tour (South of US 301) 24 B-4 Anderson -

Biographical and Cultural Issues in F. Scott Fitzgerald’S Portrayals of Women

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there missingare pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original,beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. -

Habitat Selection of Wild Turkeys in Burned Longleaf Pine Savannas

The Journal of Wildlife Management; DOI: 10.1002/jwmg.21114 Research Article Habitat Selection of Wild Turkeys in Burned Longleaf Pine Savannas ANDREW R. LITTLE,1 Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA MICHAEL J. CHAMBERLAIN, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA L. MIKE CONNER, Joseph W. Jones Ecological Research Center at Ichauway, Newton, GA 39870, USA ROBERT J. WARREN, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA ABSTRACT Frequent prescribed fire (3 yr) and selective harvest of off-site hardwoods are the primary restoration and management tools for pine (Pinus spp.) savannas in the southeastern United States. However, a knowledge gap exists in our understanding of eastern wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris) habitat selection in longleaf pine savannas and research is warranted to direct our future management decisions. Therefore, we investigated habitat selection of female turkeys in 2 longleaf pine savanna systems managed by frequent fire in southwestern Georgia during 2011–2013. We observed differential habitat selection across 2 scales (study area and seasonal area of use) and 3 seasons (fall-winter: 1 Oct–30 Jan; pre-breeding: 1 Feb–19 Apr; and summer: 16 Jun–30 Sep). During fall-winter, turkeys selected mature pine, mixed pine-hardwoods, hardwoods, and young pine stands, albeit at different scales. During pre-breeding, turkeys selected for mature pine, mixed pine-hardwoods, hardwoods, young pine, and shrub-scrub, although at different scales. During summer, turkeys also demonstrated scale-specific selection but generally selected for mature pine, hardwoods, and shrub-scrub.