Last Fifteen Minutes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ithacan, 1987-02-26

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1986-87 The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 2-26-1987 The thI acan, 1987-02-26 The thI acan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1986-87 Recommended Citation The thI acan, "The thI acan, 1987-02-26" (1987). The Ithacan, 1986-87. 17. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1986-87/17 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1980/81 to 1989/90 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1986-87 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. -- . ---· -- Warhol dies ... C ommon ' s Ja~z. ... Track places 2nd ... page 5 page 9 page 16 0""'-. - lA-:!,, 1 -~~ - -...:i \' ' •' ,--.._ ... ,,,..,~·._ . .,. THE The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Issue 17 February 26, 1987 16 pages*Free Caller IC prof. injured reports in car accident bomb Emergency surgery needed threat BY PATRICK GRAHAM but his condition is improving. B\' JERIL \'N VELDOF An Ithaca College professor sus "He is doing fine," said Liz A bomb threat over a hall phone in tained a concussion and a severe neck Snyder, Snyder's daughter. "He is on Terrace 11 B resulted in a one-and-a wound which required an emergency the road to recovery." half-hour evacuation Saturday, Feb. trachiotomy following a two-car col According to the police report and 14, according to Ithaca College Safe lision at the college's 968 entrance last witnesses' accounts, Farrell was ty and Security . -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. -

1. Dear Scott/Dear Max: the Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, Eds

NOTES INTRODUCTION F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, "THE CULTURAL WORLD," AND THE LURE OF THE AMERICAN SCENE 1. Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence, eds. John Kuehl and Jackson R. Bryer (New York: Scribner's, 1971),47. Hereafter cited as Dear Scott/Dear Max. Throughout this book, I preserve Fitzgerald's spelling, punctuation, and diacritical errors as preserved in the edited volumes of his correspondence. 2. F. Scott Fitzgerald, A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994),67. Hereafter cited as Life in Letters. 3. F. Scott Fitzgerald, F. Scott Fitzgerald on Authorship, eds. Matthew J. Bruccoli and Judith S. Baughman (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996),83. Hereafter cited as Fitzgerald on Authorship. 4. For a superb discussion of the voguish "difficulty" associated with the rise of modernist art, see Leonard Diepeveen, The Difficulties ofModernism (New York: Routledge, 2003),1-42. 5. There is a further irony that might be noted here: putting Joyce and Anderson on the same plane would soon be a good indicator of provin cialism. Fitzgerald could not have written this statement after his sojourn in France, and certainly not after encouraging his friend Ernest Hemingway's nasty parody, The Torrents of Spring (1926). Anderson may be one of the most notable casualties from the period of ambitious claimants, such as Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and William Faulkner, to a place within "the cultural world." 6. Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, tr. Susan Emanuel (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), 142. 7. "The principle of differentiation is none other than the objective and subjective distance of enterprises of cultural production with respect to the market and to expressed or tacit demand, with producers' strate gies distributing themselves between two extremes that are never, in fact, attained-either total and cynical subordination to demand or absolute independence from the market and its exigencies" (ibid., 141-42). -

SECTION-II.Pdf

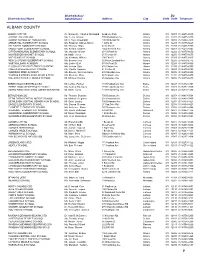

District/School Zip District/School Name Administrator Address City State Code Telephone ALBANY COUNTY ALBANY CITY SD Dr. Marguerite Vanden Wyngaard Academy Park Albany NY 12207 (518)475-6010 ALBANY HIGH SCHOOL Ms. Cecily Wilson 700 Washington Ave Albany NY 12203 (518)475-6200 ALBANY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Mr. C Fred Engelhardt 108 Whitehall Rd Albany NY 12209 (518)462-7258 ARBOR HILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Rosalind Gaines-Harrell 1 Arbor Dr Albany NY 12207 (518)475-6625 DELAWARE COMMUNITY SCHOOL Mr. Thomas Giglio 43 Bertha St Albany NY 12209 (518)475-6750 EAGLE POINT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Kendra Chaires 1044 Western Ave Albany NY 12203 (518)475-6825 GIFFEN MEMORIAL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Jasmine Brown 274 S Pearl St Albany NY 12202 (518)475-6650 MONTESSORI MAGNET SCHOOL Mr. Malik Jones 65 Tremont St Albany NY 12206 (518)475-6675 MYERS MIDDLE SCHOOL Ms. Kimberly Wilkins 100 Elbel Ct Albany NY 12209 (518)475-6425 NEW SCOTLAND ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Beverly Ivey 369 New Scotland Ave Albany NY 12208 (518)475-6775 NORTH ALBANY ACADEMY Ms. Lesley Buff 570 N Pearl St Albany NY 12204 (518)475-6800 P J SCHUYLER ACHIEVEMENT ACADEMY Ms. Jalinda Soto 676 Clinton Ave Albany NY 12206 (518)475-6700 PINE HILLS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Ms. Vibetta Sanders 41 N Allen St Albany NY 12203 (518)475-6725 SHERIDAN PREP ACADEMY Ms. Zuleika Sanchez-Gayle 400 Sheridan Ave Albany NY 12206 (518)475-6850 THOMAS S O'BRIEN ACAD OF SCI & TECH Ms. Shellette Pleat 94 Delaware Ave Albany NY 12202 (518)475-6875 WILLIAM S HACKETT MIDDLE SCHOOL Mr. -

See the 2016 Report

Frameworks for Progress The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research 2016 Annual Report The Michael J. Fox Foundation Contents is dedicated to finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease through an 2 A Note from Michael aggressively funded research 3 An Update from the CEO and the Co-Founder 6 2016 in Photos agenda and to ensuring the 8 2016 Donor Listing development of improved 11 Planned Giving therapies for those living with 13 Industry Partners 18 Corporate and Matching Gifts Parkinson’s today. 28 Tributees 44 Recurring Gifts 46 Team Fox 58 2016 Financial Highlights 64 Credits 65 Boards and Councils 2016 Annual Report 3 The Michael J. Fox Foundation Contents is dedicated to finding a cure for Parkinson’s disease through an 2 A Note from Michael aggressively funded research 3 An Update from the CEO and the Co-Founder 6 2016 in Photos agenda and to ensuring the 8 2016 Donor Listing development of improved 11 Planned Giving therapies for those living with 13 Industry Partners 18 Corporate and Matching Gifts Parkinson’s today. 28 Tributees 44 Recurring Gifts 46 Team Fox 58 2016 Financial Highlights 64 Credits 65 Boards and Councils A Note from An Update from the CEO Michael and the Co-Founder Dear Friend, Each year, we are honored to share how your unflagging determination and sheer generosity have fortified our mission to do whatever it takes to drive research. As a Todd Sherer, PhD Deborah W. Brooks Chief Executive Officer Co-Founder and Executive year full of new endeavors and tremendous Vice Chairman growth, 2016 was no exception. -

Biographical and Cultural Issues in F. Scott Fitzgerald’S Portrayals of Women

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there missingare pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original,beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. -

NYSAAA Newsletter Spring 2010

NYSAAA SPRING NEWSLETTER 10 CONFERENCE HIGHLIGHTS & PHOTOS of the 28TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE – March 16-19, 2010 PATRICK PIZZARELLI, CAA RECEIVES THE NIAAA STATE AWARD OF MERIT AL DOYLE & DON LINDELL RECEIVE THE OTIS SENNETT AWARD OF EXCELLENCE MIKE GIRUZZI, CAA, TAKES OVER AS PRESIDENT OF NYSAAA ALSO INCLUDED President’s Message INSIDE: 2010 Conference Award Winners LLeeaaddiinngg tthhee WWaayy ffoorr 2299 YYeeaarrss •• 11998811--22001100 Leading the Way for 29 Years • 1981-2010 NEW YORK STATE ATHLETIC ADMINISTRATORS’ ASSOCIATION, INC. 2010- 2011 DIRECTORY Office: 119 Pleasant View Drive, Lake Luzerne, NY 12846 Phone: 518-654-9663 Fax: 518-654-6918 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nysaaa.org Office/Staff: Executive Committee: Ex-Officio: Executive Director: Alan Mallanda, CMAA President: Mike Giruzzi, CAA NYSPHSAA: Nina Van Erk, CAA Recording Secretary: Chris Rozek President Elect: Cathy Phillips State Education Dept.: Trish Kocialski Membership: Chris Rozek (607-762-8148) Vice-President: Kevin O’Reilly, CAA Council of Administrators: Fritz Killian Conference Registration: Chris Rozek Past President: Harold Fried, CAA Conference Exhibits: Secretary: Roger Brown, CMAA State Coordinators: Larry Gillooley, CAA(518-382-2511) Treasurer: Dennis Fries, CAA Conference Planning: Mike Bromley, CAA Newsletter Editor: Alan Mallanda, CMAA NIAAA Liaison: Dave Martens Pete Shambo, CAA Leadership Training: Don Webster, CMAA Steve Young, CAA Chapter Representatives: Committee Chairs: Chapter 1: Steve Young, CAA, Horace Greeley HS Awards: Scott Sugar, -

Proquest Dissertations

ALONE IN A ROOM TOGETHER: STORIES I WANT TO TELL YOU By Jennifer L. Napolitano Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts In Creative Writing Chair: (/ fJ /'J ') 4~ -v(. f1-·----G-- Richard McCann Dean of the College 2009 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMER~AN UNIVE~.SITY UBPJ\RY qiQlO UMI Number: 1466037 Copyright 2009 by Napolitano, Jennifer L. All rights reserved INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform: 1466037 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ©COPYRIGHT by Jennifer L. Napolitano 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother. ALONE IN A ROOM TOGETHER: STORIES I WANT TO TELL YOU BY Jennifer L. Napolitano ABSTRACT Alone in a Room Together is a collection of original short fiction and nonfiction. Each piece, like each character, is independent, but linked thematically to the rest of the collection through isolation, grief, and obsession. -

The Last Tycoon"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1976 Fitzgerald's Schizoid Stahrr: America's Past, Present and Future in "The Last Tycoon" Rosalind Urbach Moss College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moss, Rosalind Urbach, "Fitzgerald's Schizoid Stahrr: America's Past, Present and Future in "The Last Tycoon"" (1976). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624943. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-r68v-t389 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FITZGERALD’S SCHIZOID STAHR: AMERICA’S PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE IN THE LAST TYCOON A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Rosalind Urbach Moss 1976 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Rosalind Urbach Moss Author Approved, April 1976 f } ^ Cjryry-JldL*. — J. Scott Donaldson Alan J . Ward James J. Thompson, Jjf. > ABSTRACT F. Scott Fitzgerald7s unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon, is a political morality play in which its author dramatizes his hopes and fears for the future of his country as he related them to ideas he found in Marx, Spengler and Edmund Wilson. -

Diaspora and Comparative Immigration

News fromzerici the Jewish Studies Program and the Center for Israeli Studies Fall 2002 From the Directors our years ago, when we conceived of this joint newsletter of American University’s Center for Israeli Studies and Jewish Studies Program, we did not imagine how different the context would be—then Fand now. More than ever, this altered context has highlighted the importance of having these two programs at American University, not only for the campus but also for the wider Washington, D.C., com- munity. As we remain committed to our core university missions, we have also responded to the chal- lenges of a changed environment. The pages of this year’s YediAUt testify to the enhanced importance of Pamela Nadell, these two academic ventures today. Director, Jewish We thank you, our readers, for your past support and welcome your continuing financial contributions. Studies Program There is a donation form on the next-to-last page of the newsletter. More than ever, your help is vital to meet the new demands placed on us and to ensure that we have sufficient resources to continue to mount our ambitious programming at American University. Diaspora and Comparative Immigration he Center for Israeli Studies held its fourth and most ambitious conference in May 2002, T“Diaspora and Comparative Immigration: Howard Wachtel, The Jewish Experience.” Sixteen papers were pre- Director, Center for sented by scholars, about half each from Israel and Israeli Studies the United States. The keynote dinner speaker was syndicated Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer, whose address was entitled “Diaspora Jewry: The Challenge of Survival.” Conference participants and attendees at lunch heard from Frank Sharry, executive director of the National Immigration Forum. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. YOU WILL BEHAVE AND OTHER STORIES by Matthew J. Getty submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing Chair: Kermitit Moyer Q k Richard McCann Dean of the Collegeor School Date 2001 American University Washington, DC 20016 W W lHW BWVERSTY LM Uft Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Country of Illusion: Imagined Geographies and Transnational Connections in F. Scott Fitzgerald's America

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Country of Illusion: Imagined Geographies and Transnational Connections in F. Scott itF zgerald's America Charles Mitchell Frye III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Frye III, Charles Mitchell, "Country of Illusion: Imagined Geographies and Transnational Connections in F. Scott itzF gerald's America" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 764. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/764 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. COUNTRY OF ILLUSION: IMAGINED GEOGRAPHIES AND TRANSNATIONAL CONNECTIONS IN F. SCOTT FITZGERALD‟S AMERICA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Charles Mitchell Frye III B.A., University of South Carolina, 2003 M.A., University of South Carolina, 2006 May 2012 “The gates were closed, the sun was gone down, and there was no beauty but the gray beauty of steel that withstands all time. Even the grief he could have borne was left behind in the country of illusion, of youth, of the richness of life, where his winter dreams had flourished.” -F.