Symmes's Theory of Concentric Spheres : Demonstrating That The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nicolaus Copernicus: the Loss of Centrality

I Nicolaus Copernicus: The Loss of Centrality The mathematician who studies the motions of the stars is surely like a blind man who, with only a staff to guide him, must make a great, endless, hazardous journey that winds through innumerable desolate places. [Rheticus, Narratio Prima (1540), 163] 1 Ptolemy and Copernicus The German playwright Bertold Brecht wrote his play Life of Galileo in exile in 1938–9. It was first performed in Zurich in 1943. In Brecht’s play two worldviews collide. There is the geocentric worldview, which holds that the Earth is at the center of a closed universe. Among its many proponents were Aristotle (384–322 BC), Ptolemy (AD 85–165), and Martin Luther (1483–1546). Opposed to geocentrism is the heliocentric worldview. Heliocentrism teaches that the sun occupies the center of an open universe. Among its many proponents were Copernicus (1473–1543), Kepler (1571–1630), Galileo (1564–1642), and Newton (1643–1727). In Act One the Italian mathematician and physicist Galileo Galilei shows his assistant Andrea a model of the Ptolemaic system. In the middle sits the Earth, sur- rounded by eight rings. The rings represent the crystal spheres, which carry the planets and the fixed stars. Galileo scowls at this model. “Yes, walls and spheres and immobility,” he complains. “For two thousand years people have believed that the sun and all the stars of heaven rotate around mankind.” And everybody believed that “they were sitting motionless inside this crystal sphere.” The Earth was motionless, everything else rotated around it. “But now we are breaking out of it,” Galileo assures his assistant. -

The Planetary Increase of Brightness During Retrograde Motion: an Explanandum Constructed Ad Explanantem

Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 54 (2015) 90e101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Studies in History and Philosophy of Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsa The planetary increase of brightness during retrograde motion: An explanandum constructed ad explanantem Christián Carlos Carman National University of Quilmes/CONICET, Roque Sáenz Peña 352, B1876BXD Bernal, Buenos Aires, Argentina article info abstract Article history: In Ancient Greek two models were proposed for explaining the planetary motion: the homocentric Received 5 May 2015 spheres of Eudoxus and the Epicycle and Deferent System. At least in a qualitative way, both models Received in revised form could explain the retrograde motion, the most challenging phenomenon to be explained using circular 17 September 2015 motions. Nevertheless, there is another explanandum: during retrograde motion the planets increase their brightness. It is natural to interpret a change of brightness, i.e., of apparent size, as a change in Keywords: distance. Now, while according to the Eudoxian model the planet is always equidistant from the earth, Epicycle; according to the epicycle and deferent system, the planet changes its distance from the earth, Deferent; fi Homocentric spheres; approaching to it during retrograde motion, just as observed. So, it is usually af rmed that the main ’ Brightness change reason for the rejection of Eudoxus homocentric spheres in favor of the epicycle and deferent system was that the first cannot explain the manifest planetary increase of brightness during retrograde motion, while the second can. In this paper I will show that this historical hypothesis is not as firmly founded as it is usually believed to be. -

“Point at Infinity Hape of the World

“Point at Infinity hape of the World Last week, we began a series of posts dedicated to thinking about immortality. If we want to even pretend to think precisely about immortality, we will have to consider some fundamental questions. What does it mean to be immortal? What does it mean to live forever? Are these the same thing? And since immortality is inextricably tied up in one’s relationship with time, we must think about the nature of time itself. Is there a difference between external time and personal time? What is the shape of time? Is time linear? Circular? Finite? Infinite? Of course, we exist not just across time but across space as well, so the same questions become relevant when asked about space. What is the shape of space? Is it finite? Infinite? It is not hard to see how this question would have a significant bearing on our thinking about immortality. In a finite universe (or, more precisely, a universe in which only finitely many different configurations of maer are possible), an immortal being would encounter the same situations over and over again, would think the same thoughts over and over again, would have the same conversations over and over again. Would such a life be desirable? (It is not clear that this repetition would be avoidable even in an infinite universe, but more on that later.) Today, we are going to take a lile historical detour to look at the shape of the universe, a trip that will take us from Ptolemy to Dante to Einstein, a trip that will uncover a remarkable confluence of poetry and physics. -

The Arithmetic of the Spheres

The Arithmetic of the Spheres Je↵ Lagarias, University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI, USA MAA Mathfest (Washington, D. C.) August 6, 2015 Topics Covered Part 1. The Harmony of the Spheres • Part 2. Lester Ford and Ford Circles • Part 3. The Farey Tree and Minkowski ?-Function • Part 4. Farey Fractions • Part 5. Products of Farey Fractions • 1 Part I. The Harmony of the Spheres Pythagoras (c. 570–c. 495 BCE) To Pythagoras and followers is attributed: pitch of note of • vibrating string related to length and tension of string producing the tone. Small integer ratios give pleasing harmonics. Pythagoras or his mentor Thales had the idea to explain • phenomena by mathematical relationships. “All is number.” A fly in the ointment: Irrational numbers, for example p2. • 2 Harmony of the Spheres-2 Q. “Why did the Gods create us?” • A. “To study the heavens.”. Celestial Sphere: The universe is spherical: Celestial • spheres. There are concentric spheres of objects in the sky; some move, some do not. Harmony of the Spheres. Each planet emits its own unique • (musical) tone based on the period of its orbital revolution. Also: These tones, imperceptible to our hearing, a↵ect the quality of life on earth. 3 Democritus (c. 460–c. 370 BCE) Democritus was a pre-Socratic philosopher, some say a disciple of Leucippus. Born in Abdera, Thrace. Everything consists of moving atoms. These are geometrically• indivisible and indestructible. Between lies empty space: the void. • Evidence for the void: Irreversible decay of things over a long time,• things get mixed up. (But other processes purify things!) “By convention hot, by convention cold, but in reality atoms and• void, and also in reality we know nothing, since the truth is at bottom.” Summary: everything is a dynamical system! • 4 Democritus-2 The earth is round (spherical). -

To Save the Phenomena

To Save the Phenomena Prof. David Kaiser Thursday, June 23, 2011, STS.003 Heavens unit Overarching questions: Are representations of astronomical phenomena true or merely useful? How does scientific knowledge travel? I. Ptolemy and the Planets II. Medieval Islamic Astronomy III. Copernican Revolutions Readings: Ptolemy, The Almagest, 5-14, 86-93; Al-Tusi, Memoir on Astronomy, 194-222; Lindberg, Beginnings of Western Science, 85-105. Timeline Ancient Medieval 500 BCE 500 CE 1450 Renaissance Enlightenment 1450 1700 1850 Modern 1850 today Thursday, June 23, 2011, STS.003 Puzzle of the Planets ―planet‖ = ―wanderer‖ 1. Planets roughly follow the path of the sun (within 5˚of the ecliptic). 2. They tend to move W to E over the year, but with varying speeds. 3. They sometimes display retrograde motion. 4. They appear brightest during retrograde. Plato‘s challenge: ―to save the phenomena.‖ ―By the assumption of what uniform and orderly motions can the apparent motions of the planets be accounted for?‖ Retrograde Motion Illustration explaining retrograde motion removed due to copyright restrictions. Mars, 2003 Geocentrism Nearly all of the ancient scholars assumed geocentrism: that the Earth sits at rest in the middle of the cosmos, while the sun, planets, and stars revolve around it. Aristotle, ca. 330 BCE ―[Some people think] there is nothing against their supposing the heavens immobile and the earth as turning on the same axis from west to east very nearly one revolution a day. But it has escaped their notice in the light of what happens around us in the air that such a notion would seem altogether absurd.‖ “That the Earth does not in any way move Aristotle, De Caelo locally” – Ptolemy, Almagest, 1:7 Flat Earth? No! Nearly all Greek scholars assumed that the Earth was a perfect sphere. -

Astronomical & Astrophysical Transactions

This article was downloaded by:[Bochkarev, N.] On: 7 December 2007 Access Details: [subscription number 746126554] Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Astronomical & Astrophysical Transactions The Journal of the Eurasian Astronomical Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713453505 Comparison and historical evolution of ancient Greek cosmological ideas and mathematical models Antonios D. Pinotsis a a Section of Astrophysics, Astronomy and Mechanics, Department of Physics, University of Athens, Athens, Greece Online Publication Date: 01 December 2005 To cite this Article: Pinotsis, Antonios D. (2005) 'Comparison and historical evolution of ancient Greek cosmological ideas and mathematical models', Astronomical & Astrophysical Transactions, 24:6, 463 - 483 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/10556790600603859 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10556790600603859 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Lecture 2: Course Overview Introduction to the Solar System

Lecture 2: Course Overview Introduction to the Solar System AST2003 Section 6218 - Spring 2012 Instructor: Professor Stanley F. Dermott Office: 216 Bryant Space Science Center Phone: 352 294 1864 email [email protected] Lecture time and place: Tuesdays (4th period: 10:40 am – 11:30 am) Thursdays (4th and 5th period) (10:40 am – 12:35 pm), FLG 210 Office hours: Tuesdays 11:45 – 12:45 pm, Thursdays 12:45 pm - 1:45 pm or by appointment Teacher Assistant: Dr Naibi Marinas (Help with Mastering Astronomy and Exam Reviews) Office: 312 Bryant Space Science Center Phone: 325 294 1848 Email: [email protected]!! Class Website: http://www.astro.ufl.edu/~marinas/astro/AST2003.html A bit about myself Russian Translation Worked with Carl Sagan while at Cornell Carl Sagan: Author and presenter of COSMOS Two papers in Nature Radar images of hydrocarbon lakes on Titan taken by Cassini spacecraft This movie, comprised of several detailed images taken by Cassini's radar instrument, shows bodies of liquid near Titan's north pole. Biggest Discovery! Published in Nature in 1994 © 1994 Nature Publishing Group © 1994 Nature Publishing Group © 1994 Nature Publishing Group Last sentence in the paper © 1994 Nature Publishing Group Structure in Debris Disks Structure in Debris DebrisDisks disks imply >km planetesimals around Debris disks imply >km main sequence stars, but planetesimals around also evidence for planets: main sequence stars, but •! inner regions are empty, also evidence for planets: probably cleared by planet formation •! inner regions are empty, -

Commentariolus Text

Commentariolus by Copernicus From the Nicolaus Copernicus Thorunensis website Our predecessors assumed, I observe, a large number of celestial spheres mainly for the purpose of explaining the planets' apparent motion by the principle of uniformity. For they thought it altogether absurd that a heavenly body, which is perfectly spherical, should not always move uniformly. By connecting and combining uniform motions in various ways, they had seen, they could make any body appear to move to any position. Callippus and Eudoxus, who tried to achieve this result by means of concentric circles, could not thereby account for all the planetary movements, not merely the apparent revolutions of those bodies but also their ascent, as it seems to us, at some times and descent at others, [a pattern] entirely incompatible with [the principle of] concentricity. Therefore for this purpose it seemed better to employ eccentrics and epicycles, [a system] which most scholars finally accepted. Yet the widespread [planetary theories], advanced by Ptolemy and most other [astronomers], although consistent with the numerical [data], seemed likewise to present no small difficulty. For these theories were not adequate unless they also conceived certain equalizing circles, which made the planet appear to move at all times with uniform velocity neither on its deferent sphere nor about its own [epicycle's] center. Hence this sort of notion seemed neither sufficiently absolute nor sufficiently pleasing to the mind. Therefore, having become aware of these [defects], I often considered whether there could perhaps be found a more reasonable arrangement of circles, from which every apparent irregularity would be derived while everything in itself would move uniformly, as is required by the rule of perfect motion. -

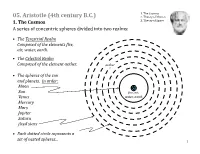

05. Aristotle (4Th Century B.C.) 2

1. The Cosmos 05. Aristotle (4th century B.C.) 2. Theory of Motion 1. The Cosmos 3. Theory of Space A series of concentric spheres divided into two realms: • The Terestrial Realm Composed of the elements fire, air, water, earth. • The Celestial Realm Composed of the element aether. aether • The spheres of the sun and planets. In order: Moon Sun fire, air, Venus water, earth Mercury Mars Jupiter Saturn fixed stars • Each dotted circle represents a set of nested spheres... 1 Earth planet 2 Earth 3 Earth 4 Earth 5 Earth 6 Earth 7 Earth 8 How many spheres? Eudoxus Callippus Aristotle Earth Moon 3 5 5 Sun 3 5 5 + 4 Venus 4 5 5 + 4 Mercury 4 5 5 + 4 Mars 4 5 5 + 4 Jupiter 4 4 4 + 3 Saturn 4 4 4 + 3 fixed stars 1 1 1 27 34 56 • Explains retrograde motion. • Aristotle requires additional spheres to counteract some of the motions of the planetary spheres. - These additional spheres are placed Between the outermost sphere of a given planet and the innermost sphere of the next planet and are one less than the numBer of spheres of the latter. 9 2. Theory of Motion • "Locomotion" = type of change (change of place). - Consequence: Motion is motion from somewhere to somewhere (finite and Bounded). • Two basic principles: I. No motion without a mover in contact with moving body. II. Distinction between: (a) Natural motion: mover is internal to moving body (b) Forced motion: mover is external to moving body Natural Motion • Mover is the "nature" of the moving body. -

Ancient Astronomy, Science and the Ancient Greeks

Published on Explorable.com (https://explorable.com) Home > Ancient Astronomy, Science And The Ancient Greeks Ancient Astronomy, Science And The Ancient Greeks Martyn Shuttleworth121.8K reads The Ancient Greeks were the driving force behind the development of western astronomy and science, their philosophers learning from the work of others and adding their own interpretations and observations. In many older textbooks, the Ancient Greeks are often referred to as the fathers of ancient astronomy, developing elegant theories and mathematical formulae to describe the wonders of the cosmos, a word that, like so many others, came to us from the Greeks. In fact, this assumption is incorrect and, whilst the Ancient Greek astronomers made huge contributions to astronomy, their knowledge was built upon the solid foundations laid by other great cultures. The Mesopotamian and Zoroastrian astronomers and astrologers, in the Fertile Crescent and the empty deserts of Persia, made many sophisticated observations and devised complex theories to describe cosmological phenomena. This ancient wisdom passed into the hands of the Greek philosophers, greedy for knowledge, when Alexander the Great conquered the region, in 331 BCE. Greece also lay at the crossroads of many trade routes, so ancient knowledge from the Indian Vedas and the Chinese astronomers further contributed to the store of insight accumulated by the Greeks. Ancient Astronomy and the Hellenistic Revolution The Ancient Greek philosophers refined astronomy, dragging it from being an observational science, with an element of prediction, into a full-blown theoretical science. The ancient astronomers used astronomy to track time and cycles, for agricultural purposes, as well as adding astrology to their sophisticated observations. -

What Was Mathematics in the Ancient World? Greek and Chinese Perspectives G E R Lloyd

`CHAPTER 1.1 What was mathematics in the ancient world? Greek and Chinese perspectives G E R Lloyd wo types of approach can be suggested to the question posed by the title of Tthis chapter. On the one hand we might attempt to settle a priori on the cri- teria for mathematics and then review how far what we [ nd in di\ erent ancient cultures measures up to those criteria. Or we could proceed more empirically or inductively by studying those diverse traditions and then deriving an answer to our question on the basis of our [ ndings. Both approaches are faced with di7 culties. On what basis can we decide on the essential characteristics of mathematics? If we thought, commonsensically, to appeal to a dictionary de[ nition, which dictionary are we to follow? 9 ere is far from perfect unanimity in what is on o\ er, nor can it be said that there are obvious, crystal clear, considerations that would enable us to adjudicate uncon- troversially between divergent philosophies of mathematics. What mathemat- ics is will be answered quite di\ erently by the Platonist, the constructivist, the intuitionist, the logicist, or the formalist (to name but some of the views on the twin fundamental questions of what mathematics studies, and what knowledge it produces). 9 e converse di7 culty that faces the second approach is that we have to have some prior idea of what is to count as ‘mathematics’ to be able to start our cross-cultural study. Other cultures have other terms and concepts and their 8 GEOGRAPHIES AnD CULTURES interpretation poses delicate problems. -

The Origin of the Idea of Material and Life Cycles in the Ancient Cosmos of Concentric Spheres

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università degli Studi di Venezia Ca' Foscari The Origin of the Idea of Material and Life Cycles in the Ancient Cosmos of Concentric Spheres Abstract Why does the world not come to a standstill? This question is positioned at the crest of the modern understanding of terrestrial cycles and spheres. In this article science historian Pietro Daniel Omodeo unpacks the original, and thus, literal notion of the spheres—from their genuine context in ancient and early modern cosmology and metaphysical doctrine—and comments on the forfeiture of stability threatening today’s spheres. Pietro Daniel Omodeo Ca’ Foscari University of Venice This product has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (GA n. 725883 EarlyModernCosmology). What shows that the spherical body is the best of all bodies is the fact that it does not perish and that it moves with the motion which precedes all motions, and also that it moves with it eternally and regularly. —Alexander of Aphrodisias, On the Cosmos The shape of the heaven is of necessity spherical; for that is the shape most appropriate to its substance and also by nature primary. —Aristotle, De coelo II.4, 286b9–10 And he [the Demiurge] bestowed on it the shape which was befitting and akin. Now for that Living Creature which is designed to embrace within itself all living creatures the fitting shape will be that which comprises within itself all the shapes there are; wherefore He wrought it into a round, in the shape of a sphere, equidistant in all directions from the center to the extremities, which of all shapes is the most perfect and the most self-similar.