Educator's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postspreading Rifting in the Adare Basin, Antarctica: Regional Tectonic Consequences

Article Volume 11, Number 8 4 August 2010 Q08005, doi:10.1029/2010GC003105 ISSN: 1525‐2027 Postspreading rifting in the Adare Basin, Antarctica: Regional tectonic consequences R. Granot Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093, USA Now at Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, 4 Place Jussieu, F‐75005 Paris, France ([email protected]) S. C. Cande Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, California 92093, USA J. M. Stock Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, 252‐21, Pasadena, California 91125, USA F. J. Davey Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand R. W. Clayton Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, 252‐21, Pasadena, California 91125, USA [1] Extension during the middle Cenozoic (43–26 Ma) in the north end of the West Antarctic rift system (WARS) is well constrained by seafloor magnetic anomalies formed at the extinct Adare spreading axis. Kinematic solutions for this time interval suggest a southward decrease in relative motion between East and West Antarctica. Here we present multichannel seismic reflection and seafloor mapping data acquired within and near the Adare Basin on a recent geophysical cruise. We have traced the ANTOSTRAT seismic stratigraphic framework from the northwest Ross Sea into the Adare Basin, verified and tied to DSDP drill sites 273 and 274. Our results reveal three distinct periods of tectonic activity. An early localized deforma- tional event took place close to the cessation of seafloor spreading in the Adare Basin (∼24 Ma). -

Office of Polar Programs

DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION DRAFT (15 January 2004) FINAL (30 August 2004) National Science Foundation 4201 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, Virginia 22230 DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SURFACE TRAVERSE CAPABILITIES IN ANTARCTICA FINAL COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL EVALUATION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Purpose.......................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE) Process .......................................................1-1 1.3 Document Organization .............................................................................................................1-2 2.0 BACKGROUND OF SURFACE TRAVERSES IN ANTARCTICA..................................2-1 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................2-1 2.2 Re-supply Traverses...................................................................................................................2-1 2.3 Scientific Traverses and Surface-Based Surveys .......................................................................2-5 3.0 ALTERNATIVES ....................................................................................................................3-1 -

Ice Shelf Advance and Retreat Rates Along the Coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica K

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 106, NO. C4, PAGES 7097–7106, APRIL 15, 2001 Ice shelf advance and retreat rates along the coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica K. T. Kim,1 K. C. Jezek,2 and H. G. Sohn3 Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio Abstract. We mapped ice shelf margins along the Queen Maud Land coast, Antarctica, in a study of ice shelf margin variability over time. Our objective was to determine the behavior of ice shelves at similar latitudes but different longitudes relative to ice shelves that are dramatically retreating along the Antarctic Peninsula, possibly in response to changing global climate. We measured coastline positions from 1963 satellite reconnaissance photography and 1997 RADARSAT synthetic aperture radar image data for comparison with coastlines inferred by other researchers who used Landsat data from the mid-1970s. We show that these ice shelves lost ϳ6.8% of their total area between 1963 and 1997. Most of the areal reduction occurred between 1963 and the mid-1970s. Since then, ice margin positions have stabilized or even readvanced. We conclude that these ice shelves are in a near-equilibrium state with the coastal environment. 1. Introduction summer 0Њ isotherm [Tolstikov, 1966, p. 76; King and Turner, 1997, p. 141]. Following Mercer’s hypothesis, we might expect Ice shelves are vast slabs of glacier ice floating on the coastal these ice shelves to be relatively stable at the present time. ocean surrounding Antarctica. They are a continuation of the Following the approach of other investigators [Rott et al., ice sheet and form, in part, as glacier ice flowing from the 1996; Ferrigno et al., 1998; Skvarca et al., 1999], we compare the interior ice sheet spreads across the ocean surface and away position of ice shelf margins and grounding lines derived from from the coast. -

Researching the Poles His Winter’S Recent “Bomb Cyclone,” Last Several Years, in Canadian Waters

MARITIME HISTORY ON THE INTERNET by Peter McCracken Researching the Poles his winter’s recent “bomb cyclone,” last several years, in Canadian waters. That Twhich froze much of the continental exhibit is now at the Canadian Museum United States, makes this seem as good a of History through September 2018 time as any to look at sources for doing (http://www.historymuseum.ca/event/ polar research. Polar research could, of the-franklin-expedition/), and then will course, include a wide range of topics—all be at Mystic Seaport after November 2018. of which would likely have some maritime A fairly basic site at http://www. connection—but here we’ll look at a few south-pole.com/ describes many aspects that seem more emphatically maritime, of Antarctic exploration, with a particular such as scientific research and exploration. focus on letters, telegrams, documents, and Given the manner in which polar re- especially stamps, to tell these stories. Rus- gions bring nations’ borders together in sell Potter maintains an overview of many often-confusing ways, it’s not surprising Arctic expeditions and explorers at http:// that many different countries sponsor po- visionsnorth.blogspot.com/p/arctic- lar research programs. The Norwegian exploration-brief-history-of.html, and Polar Institute, at http://www.npolar.no/ has a variety of interesting additional con- en/, for instance, focuses on both poles; tent about Arctic exploration and literature. this is not a surprise, given the proximity Myriad pages honor the memory of of the North Pole, and their history of ex- Sir Ernest Shackleton, particularly sur- find the most recent literature, they do have ploration of the South Pole by Roald rounding the epic struggle and eventual earlier content and they are still available Amundsen and others. -

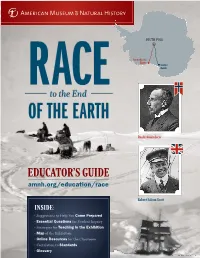

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Texts G7 Sout Pole Expeditions

READING CLOSELY GRADE 7 UNIT TEXTS AUTHOR DATE PUBLISHER L NOTES Text #1: Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen (Photo Collages) Scott Polar Research Inst., University of Cambridge - Two collages combine pictures of the British and the Norwegian Various NA NA National Library of Norway expeditions, to support examining and comparing visual details. - Norwegian Polar Institute Text #2: The Last Expedition, Ch. V (Explorers Journal) Robert Falcon Journal entry from 2/2/1911 presents Scott’s almost poetic 1913 Smith Elder 1160L Scott “impressions” early in his trip to the South Pole. Text #3: Roald Amundsen South Pole (Video) Viking River Combines images, maps, text and narration, to present a historical NA Viking River Cruises NA Cruises narrative about Amundsen and the Great Race to the South Pole. Text #4: Scott’s Hut & the Explorer’s Heritage of Antarctica (Website) UNESCO World Google Cultural Website allows students to do a virtual tour of Scott’s Antarctic hut NA NA Wonders Project Institute and its surrounding landscape, and links to other resources. Text #5: To Build a Fire (Short Story) The Century Excerpt from the famous short story describes a man’s desperate Jack London 1908 920L Magazine attempts to build a saving =re after plunging into frigid water. Text #6: The North Pole, Ch. XXI (Historical Narrative) Narrative from the =rst man to reach the North Pole describes the Robert Peary 1910 Frederick A. Stokes 1380L dangers and challenges of Arctic exploration. Text #7: The South Pole, Ch. XII (Historical Narrative) Roald Narrative recounts the days leading up to Amundsen’s triumphant 1912 John Murray 1070L Amundsen arrival at the Pole on 12/14/1911 – and winning the Great Race. -

Download Preprint

Ross and Siegert: Lake Ellsworth englacial layers and basal melting 1 1 THIS IS AN EARTHARXIV PREPRINT OF AN ARTICLE SUBMITTED FOR 2 PUBLICATION TO THE ANNALS OF GLACIOLOGY 3 Basal melt over Subglacial Lake Ellsworth and it catchment: insights from englacial layering 1 2 4 Ross, N. , Siegert, M. , 1 5 School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, 6 UK 2 7 Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK Annals of Glaciology 61(81) 2019 2 8 Basal melting over Subglacial Lake Ellsworth and its 9 catchment: insights from englacial layering 1 2 10 Neil ROSS, Martin SIEGERT, 1 11 School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK 2 12 Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK 13 Correspondence: Neil Ross <[email protected]> 14 ABSTRACT. Deep-water ‘stable’ subglacial lakes likely contain microbial life 15 adapted in isolation to extreme environmental conditions. How water is sup- 16 plied into a subglacial lake, and how water outflows, is important for under- 17 standing these conditions. Isochronal radio-echo layers have been used to infer 18 where melting occurs above Lake Vostok and Lake Concordia in East Antarc- 19 tica but have not been used more widely. We examine englacial layers above 20 and around Lake Ellsworth, West Antarctica, to establish where the ice sheet 21 is ‘drawn down’ towards the bed and, thus, experiences melting. Layer draw- 22 down is focused over and around the NW parts of the lake as ice, flowing 23 obliquely to the lake axis, becomes afloat. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

Mount Harding, Grove Mountains, East Antarctica

MEASURE 2 - ANNEX Management Plan for Antarctic Specially Protected Area No 168 MOUNT HARDING, GROVE MOUNTAINS, EAST ANTARCTICA 1. Introduction The Grove Mountains (72o20’-73o10’S, 73o50’-75o40’E) are located approximately 400km inland (south) of the Larsemann Hills in Princess Elizabeth Land, East Antarctica, on the eastern bank of the Lambert Rift(Map A). Mount Harding (72°512 -72°572 S, 74°532 -75°122 E) is the largest mount around Grove Mountains region, and located in the core area of the Grove Mountains that presents a ridge-valley physiognomies consisting of nunataks, trending NNE-SSW and is 200m above the surface of blue ice (Map B). The primary reason for designation of the Area as an Antarctic Specially Protected Area is to protect the unique geomorphological features of the area for scientific research on the evolutionary history of East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS), while widening the category in the Antarctic protected areas system. Research on the evolutionary history of EAIS plays an important role in reconstructing the past climatic evolution in global scale. Up to now, a key constraint on the understanding of the EAIS behaviour remains the lack of direct evidence of ice sheet surface levels for constraining ice sheet models during known glacial maxima and minima in the post-14 Ma period. The remains of the fluctuation of ice sheet surface preserved around Mount Harding, will most probably provide the precious direct evidences for reconstructing the EAIS behaviour. There are glacial erosion and wind-erosion physiognomies which are rare in nature and extremely vulnerable, such as the ice-core pyramid, the ventifact, etc. -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION