The EU's Northern Dimension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Success Story Or a Failure? : Representing the European Integration in the Curricula and Textbooks of Five Countries

I Inari Sakki A Success Story or a Failure? Representing the European Integration in the Curricula and Textbooks of Five Countries II Social psychological studies 25 Publisher: Social Psychology, Department of Social Research, University of Helsinki Editorial Board: Klaus Helkama, Chair Inga Jasinskaja-Lahti, Editor Karmela Liebkind Anna-Maija Pirttilä-Backman Kari Mikko Vesala Maaret Wager Jukka Lipponen Copyright: Inari Sakki and Unit of Social Psychology University of Helsinki P.O. Box 4 FIN-00014 University of Helsinki I wish to thank the many publishers who have kindly given the permission to use visual material from their textbooks as illustrations of the analysis. All efforts were made to find the copyright holders, but sometimes without success. Thus, I want to apologise for any omissions. ISBN 978-952-10-6423-4 (Print) ISBN 978-952-10-6424-1 (PDF) ISSN 1457-0475 Cover design: Mari Soini Yliopistopaino, Helsinki, 2010 III ABSTRAKTI Euroopan yhdentymisprosessin edetessä ja syventyessä kasvavat myös vaatimukset sen oikeutuksesta. Tästä osoituksena ovat muun muassa viimeaikaiset mediassa käydyt keskustelut EU:n perustuslakiäänestysten seurauksista, kansalaisten EU:ta ja euroa kohtaan osoittamasta ja tuntemasta epäluottamuksesta ja Turkin EU-jäsenyydestä. Taloudelliset ja poliittiset argumentit tiiviimmän yhteistyön puolesta eivät aina riitä kansalaisten tuen saamiseen ja yhdeksi ratkaisuksi on esitetty yhteisen identiteetin etsimistä. Eurooppalaisen identiteetin sanotaan voivan parhaiten muodostua silloin, kun perheen, koulutuksen -

Official Journal C 374 Volume 42 of the European Communities 23 December 1999

ISSN 0378–6986 Official Journal C 374 Volume 42 of the European Communities 23 December 1999 English edition Information and Notices Notice No Contents Page I Information ...... II Preparatory Acts Committee of the Regions Session of September 1999 1999/C 374/01 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Communication from the Commission on A northern dimension for the policies of the Union’ . 1 1999/C 374/02 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Amended proposal for Council Directive on assessment of the effects of certain plans and programmes on the environment’ . 9 1999/C 374/03 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Proposal for a Council Regulation (EC) amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 1210/90 of 7 May 1990 on the establishment of the European Environment Agency and the European Information and Observation Network’ . 10 1999/C 374/04 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Commission report to the European Council “Better lawmaking 1998 — a shared responsibility”’ . 11 1999/C 374/05 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Institutional Aspects of Enlargement “Local and Regional Government at the heart of Europe”’ . 15 1999/C 374/06 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on the ‘Implementation of EU law by the regions and local authorities’. 25 Price: 19,50 EUR EN (Continued overleaf) Notice No Contents (Continued) Page 1999/C 374/07 Opinion of the Committee of the Regions on ‘the Proposal for a European Parliament and Council decision amending Decision No. 1254/96/EC laying down a series of guidelines for trans-European energy networks’ . -

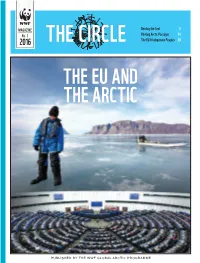

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

Rethinking European Union Foreign Policy Prelims 7/6/04 9:46 Am Page Ii

prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page i rethinking european union foreign policy prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page ii EUROPE IN CHANGE T C and E K already published The formation of Croatian national identity A centuries old dream . Committee governance in the European Union ₍₎ Theory and reform in the European Union, 2nd edition . , . , German policy-making and eastern enlargement of the EU during the Kohl era Managing the agenda . The European Union and the Cyprus conflict Modern conflict, postmodern union The time of European governance An introduction to post-Communist Bulgaria Political, economic and social transformation The new Germany and migration in Europe Turkey: facing a new millennium Coping with intertwined conflicts The road to the European Union, volume 2 Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania () The road to the European Union, volume 1 The Czech and Slovak Republics () Europe and civil society Movement coalitions and European governance Two tiers or two speeds? The European security order and the enlargement of the European Union and NATO () Recasting the European order Security architectures and economic cooperation The emerging Euro-Mediterranean system . . prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page iii Ben Tonra and Thomas Christiansen editors rethinking european union foreign policy Modern conflict, postmodern union Security architectures and economic cooperation MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page iv Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. -

Canada's Northern Strategy Is a Complex Policy Space, Thus It Is Not Surprising That There Are Differing Views on How Ottawa Should Deal with It

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». •,,' J CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE COLLEGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES NSP 1 / PSN 1 Canadian Northern Strategy: Stopping the ebb and flow By/par Capl(N) D. Haweo This paper was written by a student La presente etude a eM redigee par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du College des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire a l'une of the Programme of Studies. The paper des exigences du programme. L'etude is a scholastic document, and thus est un document qui se rapporte all. contains facts and opinions, which the cours et contient done des faits et des author alone considered appropriate opinions que seull'auteur considere and correct for the subject. -

Nordic States and European Integration

NORDIC STATES AND EUROPEAN INTEGRATION: THE “ME” REGION? Summary of remarks by Alyson JK Bailes, Faculty of Political Science, University of Iceland At the History Congress (Söguþing), 10 June 2012 in Reykjavik My title is rather provocatively chosen to reflect the phrase ‘the Me generation’. It reflects my aim to discuss how far the factor of national identity can be – and perhaps needs to be - used to explain the Nordic region’s varied and ambivalent engagement with European integration in the late 20th and 21st centuries. First however I would like to offer some comparison between the attitudes of the five Nordic states and of Britain – which shares with them an above-average level of Euro-scepticism in public opinion. All these nations belong to Europe’s Western and Northern periphery: and since practically all historic threats to them have come from the East and South, they can only realistically hope for powers further West to come to their rescue. That gives them an existential stake in relations with the USA which, at least, qualifies the value they can see in purely European cooperation. Geographical position also makes all of them maritime powers to some extent (in Sweden and Finland’s case, in the Baltic setting) – and geopolitical theory tells us that such powers tend to be flexible, mobile and liberal, hence not happy about being tied down in static continental systems. Among shared internal characteristics one may mention the early definition and importance of national laws and representative institutions, which all these countries have an instinct to defend against the imposition of alien standards. -

Northern Dimension: Towards a More Sustainable Future

Northern Dimension: Towards a More Sustainable Future www.northerndimension.info Towards a More Sustainable Future During its 20 years of operation, the four The Northern Dimension thematic partnerships of the ND solves acute problems through concrete achievements: The Northern Dimension (ND) is a com- mon policy of the EU, Russia, Norway and • The ND Environmental Partnership (NDEP) has contributed to the cleaning of the Baltic Sea Iceland that provides proven instruments by catalyzing wastewater treatment projects and platforms to jointly tackle common in Northwest Russia and Belarus, and reduced challenges. the danger of radiological contamination of the Arctic Sea by addressing the legacy of the The Northern Dimension area covers the operations of Soviet nuclear infrastructure. European North, including the Arctic, Bar- • The ND Partnership in Public Health and The Northern Dimension focuses on concrete problem solving and people-to-people cooperation in the ND area. ents and Baltic Sea regions, and North- Social Well-being (NDPHS) has combatted west Russia. acute health challenges such as HIV/AIDS by cross-border exchange of information and The Partnerships flexibly re-direct their thematic sharing of best practices. focus on new emerging challenges and oppor- tunities according to priorities on the Partners’ agenda. • NDEP initiates projects on minimizing black Changes in climate, technology and carbon emissions. demography transform societies in the • NDPHS works on healthy ageing and societal globalizing world. New challenges and implications of COVID-19 epidemic. opportunities emerge in areas such as • ND Partnership on Transport and Logistics environment, health, transport and people- (NDPTL) focuses on digitalization of transport to-people interaction. -

The European Investment Bank in the Baltic Sea Region

The European Investment Bank in the Baltic Sea Region The EIB supports the Baltic Sea Region’s long tradition of cross-border cooperation by financing long-term projects involving transport, energy, the environment, research, development and innovation (RDI), climate action and SMEs. © LANXESS AG Kunststoff Technikum European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank • European Investment Bank What the EIB can do for the Baltic The European Commission’s overall objec- To connect the region, we finance infra- Sea Region tives for the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea structure to integrate parts of the Nordic- Region are: Baltic area into a larger Baltic Sea Region. The Baltic Sea Region is home to almost • to save the sea; EIB loans have supported the construc- 100 million people, and eight EU Member • to connect the region; and tion or improvement of bridges, tunnels, States and the Russian Federation share its • to increase prosperity. port facilities and railway links. Improved 8 000 km-long coastline. Each objective is accompanied by indica- and safer energy production and energy tors and targets. transmission lines have also been high on The region has a long tradition of cross- the agenda. border cooperation even though each As the bank of the EU, the EIB has a special country has its own priorities and char- responsibility to contribute to the success To increase prosperity, we support a large acteristics, economic imperatives and of this strategy. number of research, development and political concerns. -

Basic Information on the Northern Dimension

MINISTRY FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS OCTOBER 2006 HELSINKI THE NORTHERN DIMENSION; BASIC INFORMATION The Northern Dimension Discussion on the Northern Dimension first started when Finland, Sweden and Norway in the autumn of 1994 were preparing their referendums on joining the European Union. Officially Finland’s initiative was presented in September 1997 in Rovaniemi in a speech given by Prime Minister Paavo Lipponen. Finland drew the attention of the EU member states and the Commission to the possibilities offered by Northern Europe, on one hand, and to various challenges, on the other. Development of co-operation in the region between the enlarging Union and the Russian Federation was aimed at enhancing stability, sustainable development and positive interdependency. The Northern Dimension became official EU policy in June 1999, as the general political guidelines for the Northern Dimension were adopted by the European Council. The actual work on developing co-operation between the Union and the partner countries Norway, Iceland, the Russian Federation and the then EU candidate states Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Estonia, was begun during Finland’s presidency in the autumn 1999. Canada and the United States are participating in the co-operation as observer countries. Canada is also contributing to the Northern Dimension partnerships (see below). The Action Plan In June 2000 during Portugal’s presidency, the First Action Plan for the Northern Dimension for the years 2000 -2003 was adopted by the European Council in Feira. The Plan set out objectives and defined actions to be undertaken in different sectors, such as environment and natural resources, justice and home affairs, support to trade and investments, public health, energy, transport, information society, nuclear safety, scientific research and cross-border co-operation. -

9808/01 Mip/CY/Ct 1 DG G COUNCIL of THE

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 12 June 2001 (13.06) THE EUROPEAN UNION (OR. fr) 9808/01 Interinstitutional File: 2001/0121 (CNS) LIMITE ECOFIN 163 ENV 324 NIS 45 COVER NOTE from : Mr Bernhard ZEPTER, Deputy Secretary-General of the European Commission date of receipt : 6 June 2001 to : Mr Javier SOLANA, Secretary-General/High Representative Subject : Proposal for a Council Decision granting a Community guarantee to the European Investment Bank against losses under a special lending action for selected environmental projects in the Baltic Sea basin of Russia under the Northern Dimension Delegations will find attached Commission document COM(2001) 297 final. Encl. COM(2001) 297 final 9808/01 mip/CY/ct 1 DG G EN COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 5.6.2001 COM(2001) 297 final 2001/0121(CNS) Proposal for a COUNCIL DECISION granting a Community guarantee to the European Investment Bank against losses under a special lending action for selected environmental projects in the Baltic Sea basin of Russia under the Northern Dimension (presented by the Commission) EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM 1. INTRODUCTION The Northern Dimension was first recognised EU-wide at the Luxembourg European Council in December 1997. The Vienna European Council (December 1998) and the Cologne European Council (June 1999) developed it into a more concrete concept. In November 1999, the Finnish EU Presidency held a Foreign Ministerial Conference on the Northern Dimension and, one month later, the Helsinki European Council invited the Commission to prepare an Action Plan which was endorsed by the Feira European Council in June 2000. The Northern Dimension covers the geographical area from Iceland to the west across to North West Russia, from the Norwegian, Barents and Kara Seas in the North to the Southern coast of the Baltic Sea. -

Šiauliai University

âIAULIAI UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY Sigita VITKUVIENƠ LANGUAGE OF THE DOCUMENTS OF LITHUANIA’S INTEGRATION INTO THE EUROPEAN UNION. ASPECTS OF TRANSLATION. Master’s work Academic advisers: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kazimieras Romualdas äuperka Assist. Jnjratơäukauskienơ âiauliai, 2005 âIAULIǏ UNIVERSITETAS HUMANITARINIS FAKULTETAS ANGLǏ FILOLOGIJOS KATEDRA Sigita VITKUVIENƠ LIETUVOS STOJIMO Ʋ EUROPOS SĄJUNGĄ DOKUMENTǏ KALBA. VERTIMO ASPEKTAI. Magistro darbas Darbo vadovai: Prof. Hab. Dr. Kazimieras Romualdas äuperka Asist. Jnjratơäukauskienơ âiauliai, 2005 2 SANTRAUKA Sigita Vitkuvienơ Lietuvos stojimo Ƴ Europos Sąjungą dokumentǐ kalba. Vertimo aspektai. Magistro darbas. Tiek Lietuvoje, tiek kitose ãalyse vis labiau domimasi vertimo teorijos ir praktikos klausimais. Lietuvai Ƴstojus Ƴ Europos Sąjungą (ES), vertimo teorijos ir praktikos tyrimai tampa kaskart aktualesni ir mnjVǐãaliai. âio tyrimo tikslas yra aptarti euroåargoną (taip vadinama ES institucijose vartojama specifinơ dalykinơ kalba) vertimo aspektu. Apåvelgiama teorinơ medåiaga apie tą ES kalbą, iãsamiai nagrinơjami jos apibrơåimai, pateikiami skirtingi poåLnjriai Ƴ Mą, detaliai aptariamos jos ypatybơs. Magistro darbe pateikiama daug ES terminǐ ir lietuviãNǐ Mǐ vertimo ekvivalentǐ, iliustruojanþLǐ vertimo sunkumus, su kuriais susiduriama verþiant ES dokumentus, taip pat euroåargono Ƴtaką lietuviǐ kalbai. Atlikta 700 anglǐ-lietuviǐ kalbǐ ES terminǐ analizơ kalbos reliatyvumo pagrindu. Siekiant atskleisti ES institucijose vartojamos kalbos specifiãkumą, atliktas tyrimas, aptarti tyrimo rezultatai, analizuojamos respondentǐ netinkamai atlikto vertimo prieåastys. SUMMARY Sigita Vitkuvienơ Language of the Documents of Lithuania’s Integration into the European Union. Aspects of Translation. Master’s work. The issues of translation theory and practice are of great interest in Lithuania as well as in other countries. Researches on translation theory and practice have become even more relevant for Lithuania with its joining the European Union (EU). -

Avoiding a New 'Cold War': the Future of EU-Russia Relations in the Context Of

SPECIALREPORT SR020 March 2016 Avoiding a New 'Cold War' The Future of EU-Russia Relations in the Context of the Ukraine Crisis Editor LSE IDEAS is an Institute of Global Affairs Centre Dr Cristian Nitoiu that acts as the School’s foreign policy think tank. Through sustained engagement with policymakers and opinion-formers, IDEAS provides a forum that IDEAS Reports Editor informs policy debate and connects academic research Joseph Barnsley with the practice of diplomacy and strategy. IDEAS hosts interdisciplinary research projects, produces working papers and reports, holds public Creative Director and off-the-record events, and delivers cutting-edge Indira Endaya executive training programmes for government, business and third-sector organisations. Cover image source The ‘Dahrendorf Forum - Debating Europe’ is a joint www.istockphoto.com initiative by the Hertie School of Governance, the London School of Economics and Political Science and Stiftung Mercator. Under the title “Europe and the World” the project cycle 2015-2016 fosters research and open debate on Europe’s relations with five major regions. lse.ac.uk/IDEAS Contents SPECIALREPORT SR020 March 2016 Avoiding A New ‘Cold War’: The Future of EU-Russia Relations in the Context of the Ukraine Crisis EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Cristian Nitoiu PRefaCE 3 Vladislav Zubok CONTRIBUTORS 6 PART I. EU-RUSSIA RelaTIONS: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE Could it have been Different? 8 The Evolution of the EU-Russia Conflict and its Alternatives Tuomas Forsberg and Hiski Haukkala Russia and the EU: A New Future Requested 15 Fyodor Lukyanov Why the EU-Russia Strategic Partnership Could Not Prevent 20 a Confrontation Over Ukraine Tom Casier Security Policy, Geopolitics and International Order 26 in EU-Russia Relations during the Ukraine Crisis Roy Allison Member States’ Relations with Russia: Solidarity and Spoilers 33 Maxine David PART II.