US SUPREME COURT: the 2020–2021 TERM Program Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Larry Cosme FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS

Representing Members From: FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS ASSOCIATION AGRICULTURE OIG Forest Service 1100 Connecticut Ave NW ▪ Suite 900 ▪ Washington, D.C. 20036 CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY COMMERCE Export Enforcement Phone: 202-293-1550 ▪ www.fleoa.org OIG NOAA Fisheries Law Enforcement DEFENSE Air Force - OSI Army - CID Defense Criminal Investigative Service June 10, 2021 Naval Criminal Investigative Service OIG Police EDUCATION - OIG Honorable Gary Peters Honorable Rob Portman ENERGY National Nuclear Security Administration Chairman Ranking Member OIG ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY United States Senate HSGAC United States Senate HSGAC CID OIG Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20510 FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION OIG FEDERAL HOUSING FINANCE AGENCY – OIG FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM Federal Reserve Board Dear Chairman Peters and Ranking Member Portman, Federal Reserve Police FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING CENTER GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION - OIG HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES We write to you today to express our growing concern over the nomination of Kiran Ahuja as the Food & Drug Administration OIG next Office of Personnel Management (OPM) Director. Although we have not weighed in on this HOMELAND SECURITY Border Patrol nomination in the past, recent developments have generated concern in our association. Coast Guard Investigative Service Immigration & Customs Enforcement Customs & Border Protection Federal Air Marshal Service A nominee who would become the leader of the human resources, payroll and training entity within Federal Protective Service U.S. Secret Service the federal government with direct authority over millions of federal employees, including the over Transportation Security Administration OIG 100,000 federal law enforcement officers that protect and defend this nation every day, that often HOUSING & URBAN DEVELOPMENT - OIG becomes an arbiter of both agency and Congressional policies, should have a past record that shows INTERIOR Bureau of Indian Affairs fairness, equity and sensitivity to everyone. -

In the United States Court of Federal Claims

In the United States Court of Federal Claims No. 07-589C (Filed: February 13, 2017)* *Opinion originally filed under seal on February 1, 2017 ) JEFFREY B. KING, SCOTT A. ) AUSTIN, KEVIN J. HARRIS, and ) JOHN J. HAYS, on their own behalf ) and on behalf of a class of others ) similarly situated, ) Back Pay Act; 5 U.S.C. § 5596; Class ) Action; FBI Police; 28 U.S.C. § 540C; Plaintiffs, ) Cross-Motions for Summary ) Judgment; RCFC 56 v. ) ) THE UNITED STATES, ) ) Defendant. ) ) Joseph V. Kaplan, Washington, DC, for plaintiffs. Alexander O. Canizares, Commercial Litigation Branch, Civil Division, United States Department of Justice, Washington, DC, with whom were Martin F. Hockey, Jr., Assistant Director, Robert E. Kirschman, Jr., Director, and Benjamin C. Mizer, Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General, for defendant. O P I N I O N FIRESTONE, Senior Judge. Pending before the court are cross-motions for summary judgment pursuant to Rule 56 of the Rules of the Court of Federal Claims (“RCFC”) filed by named plaintiffs Jeffrey B. King, Scott A. Austin, Kevin J. Harris, and John J. Hays, on behalf of a certified class of current and former police officers employed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) and defendant the United States (“the government”). The plaintiffs allege that they are owed back pay and other relief under the Tucker Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1491(a), and the Back Pay Act, 5 U.S.C. § 5596, on the grounds that the FBI has established a police force under 28 U.S.C. § 540C (“section 540C”) but has failed to pay police officers in accordance with the terms of section 540C. -

TITLE (And Volume Number)

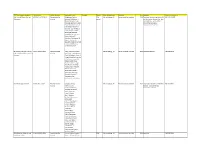

TITLE (and Volume Number) Call Number Author, Primary Author(s), Added Editor(s) Edition Place of Publication Publisher Year Subject(s) Series (e.g., PBI Number) 10th Annual Oil and Gas Law KFP258 .A1 A715 2018 Pennsylvania Bar Spigelmyer, David J; 10th Mechanicsburg, PA Pennsylvania Bar Institute 2018 Petroleum Law and Legislation; Oil PBI 2018-10095R Colloquium Institute Anthony R Holtzman; J annual and Gas Leases; Natural Gas--Law Nicholas Ranjan; Amy L and Legislation; Gas Industry-- Barrette; Jeremy A Mercer; Environmental Aspects; David J Raphael; Curtis N Environmental Protection Stambaugh; Michael A Braymer; Sean W Moran; Carl F Staiger; David R Overstreet; David G Mandelbaum; Andrew T Bockis; Michael D Brewster; Christopher W Rogers; Stephen W Saunders; Robert J Burnett; Thomas S McNamara; Joseph M Scipione 20 [Twenty] Hot Tips in Family KFP94 .A75 A15 2015 Pennsylvania Bar Helvy, Paul; Ann V Levin; Mechanicsburg, PA Pennsylvania Bar Institute 2015 Domestic Relations PBI 2015-8878 Law: Unique Problems, Practical Institute Jeff Landers; Ann M Funge; Solutions David N Hofstein; Scott J G Finger; Susan Ardisson; Lea E Anderson; Tanya Witt; Natalie Webb; Kaye Redburn; Kirk C Stange; Paul Purcell; Elizabeth L Hughes; Kevin R Brown; Robert J Fall; Jerry Shoemaker; James A Wolfinger; Mary Sue Ramsden; Richard F Brabender; Lea F Anderson; Carol A Behers 2014 Technology Institute KF320 .A9 A15 2014 Pennsylvania Bar Avrigian, Mason; Mechanicsburg, PA Pennsylvania Bar Institute 2014 Information Storage and Retrieval PBI 2014-8056 Institute -

Legislative Branch Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2001

S. HRG. 106–820 LEGISLATIVE BRANCH APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2001 HEARINGS BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 4516, 4577, and 5657/S. 2603 AN ACT MAKING APPROPRIATIONS FOR THE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2001, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES Architect of the Capitol (except House items) Congressional Budget Office General Accounting Office Government Printing Office Joint Committee on Taxation Joint Economic Committee Library of Congress Office of Compliance U.S. Capitol Police Board U.S. Senate Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 62–802 cc WASHINGTON : 2001 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont SLADE GORTON, Washington FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky TOM HARKIN, Iowa CONRAD BURNS, Montana BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HARRY REID, Nevada JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HERB KOHL, Wisconsin ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah PATTY MURRAY, Washington BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois JON KYL, Arizona STEVEN J. CORTESE, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director JAMES H. -

GAO-07-815 Federal Law Enforcement Mandatory Basic Training

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters GAO August 2007 FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT Survey of Federal Civilian Law Enforcement Mandatory Basic Training GAO-07-815 August 2007 FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT Accountability Integrity Reliability Highlights Survey of Federal Civilian Law Highlights of GAO-07-815, a report to Enforcement Mandatory Basic Training congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Federal law enforcement officers Based on the responses of the 105 federal civilian law enforcement (LEO) are required to complete components surveyed, GAO identified 76 unique mandatory basic training mandatory basic training in order programs. Among these, four programs in particular were cited by the to exercise their law enforcement components more often than others as mandatory for their LEOs (see table). authorities. Of the remaining 72 unique basic training programs, each was common to GAO was asked to identify federal just one to three components. Some of these basic training programs are mandatory law enforcement basic required for job series classifications representing large portions of the training programs. This report overall LEO population. For example, newly hired employees at the Federal builds on GAO’s prior work Bureau of Prisons encompass 159 different job series classifications. This surveying federal civilian law large number of job series classifications is required to take the same two enforcement components regarding unique basic training programs. their functions and authorities (see GAO-07-121, December 2006). GAO defined an LEO as an individual Of the 105 components surveyed, 37 components reported exclusively using authorized to perform any of four the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC)—the largest single functions: conduct criminal provider of law enforcement training for the federal government. -

G1'lo,Gtl.C Domain/Mp O.S

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. 151166 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this , material has been g1'lO,gtl.C Domain/mP o.s. Depart'lt'ent of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires pormission of the ~wner. /$llb~ U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs December 1994, NCJ-1S1166 Federal Law Enforcement Officers, 1993 By Brian A. Reaves, Ph.D. officers worked for the FBI, which FBI agents accounted for about a BJS Statistician employed 10,075 agents; the Federal fourth of Federal officers classified Bureau of Prisons (BOP), which had in the criminal investigation and en As of December 1993, Federal agen 9,984 correctional officers; or the Im forcementcategory. Nearly all of the cies employed about 69,000 full-time migration and Naturalization Service 10,075 FBI agents nationwide were personnel authorized 'to make arrests (INS), which reported 9,466 officers included in this category. These Fed and carry firearms. according to data as of December 1993 . eral officers have broad investigative • provided by the agencies in response to a survey conducted by the Bureau .; ,,: ,'~'::": "'X:":. "'.:' -- .. ",' " ~ :,' ::.'" ... 7" ...... .' , i .BIg' libgnts:\"t;'~ ';-i', '. ,,',:' .... '.''- .' ,: .-: .. , . '- '... of Justice Statistics (8JS). -

The Myth of Fourth Amendment Circularity Matthew B

The Myth of Fourth Amendment Circularity Matthew B. Kugler† and Lior Jacob Strahilevitz†† The Supreme Court’s decision in Katz v United States made people’s reasona- ble expectations of privacy the touchstone for determining whether state surveillance amounts to a search under the Fourth Amendment. Ever since Katz, Supreme Court justices and numerous scholars have referenced the inherent circularity of taking the expectations-of-privacy framework literally: people’s expectations of privacy de- pend on Fourth Amendment law, so it is circular to have the scope of the Fourth Amendment depend on those same expectations. Nearly every scholar who has writ- ten about the issue has assumed that the circularity of expectations is a meaningful impediment to having the scope of the Fourth Amendment depend on what ordinary people actually expect. But no scholar has tested the circularity narrative’s essential premise: that popular sentiment falls into line when salient, well-publicized changes in Fourth Amendment law occur. Our Article conducts precisely such a test. We conducted surveys on census- weighted samples of US citizens immediately before, immediately after, and long after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Riley v California. The decision in Riley was unanimous and surprising. It substantially altered Fourth Amendment law on the issue of the privacy of people’s cell phone content, and it was a major news story that generated relatively high levels of public awareness in the days after it was decided. We find that the public began to expect greater privacy in the contents of their cell phones immediately after the Riley decision, but this effect was small and confined to the 40 percent of our sample that reported having heard of the deci- sion. -

Federal Law Enforcement Pay and Benefits ______

FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT PAY AND BENEFITS ______ REPORT TO THE CONGRESS Working for America UNITED STATES OFFICE OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT Kay Coles James, Director July 2004 A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF THE OFFICE OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT I am pleased to present the Office of Personnel Management’s (OPM’s) report to Congress on law enforcement classification, pay, and benefits. This report responds to section 2(b) of the Federal Law Enforcement Pay and Benefits Parity Act of 2003, Public Law 108-196, which calls for OPM to submit a report to Congress providing a comparison of classification, pay, and benefits among Federal law enforcement personnel throughout the Government and to make recommendations to correct any unwarranted differences. The issues we address in this report are critical in light of the many dramatic challenges that face the Federal law enforcement community in the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the Oklahoma City bombing of April 19, 1995, as well as our Nation’s ongoing all-out war on terrorism. The specter of those horrific events and ongoing need to secure our homeland demand we pay careful attention to the strategic management of our Federal law enforcement personnel. The report provides relevant background information on the current state of affairs in Federal law enforcement pay and benefits and an analysis of the key factors that must be considered in making policy judgments about three critical areas: (1) retirement benefits, (2) classification and basic pay, and (3) premium pay. At present, considerable and sometimes confusing differences exist among law enforcement personnel in those three areas. -

Why Justice Thomas Should Speak at Oral Argument

:+<-867,&(7+20$66+28/'63($.$725$/ $5*80(17 ∗ 'DYLG$.DUS , ,1752'8&7,21 ,, 7+(9$/8(2)25$/$5*80(17 ,,, 7+(6281'2)6,/(1&( ,9 7+(())(&72)6,/(1&( 9 ³0<&2//($*8(66+28/'6+8783´ $ 'HFRUXP % /LVWHQLQJ & .HHSLQJDQ2SHQ0LQG ' %URDGHQLQJWKH'HEDWH ( 'LPLQLVKLQJ+LV6WDWXUH 9, 7+(32:(52):25'6 9,, &21&/86,21 ,,1752'8&7,21 7KHRUDODUJXPHQWEHIRUHWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV6XSUHPH&RXUWLQ0RUVHY )UHGHULFNEHJDQDWDPLQW\SLFDOIDVKLRQOLNHDKLJKVSHHGJDPH RIFKHVV)RUW\WZRVHFRQGVLQWRWKHDUJXPHQW-XVWLFH$QWKRQ\.HQQHG\ FXWRIIWKHDGYRFDWHLQPLGVHQWHQFH)RUWKHQH[WKRXUDQGWHQPLQXWHV WKH-XVWLFHVLQWHUUXSWHGWKHODZ\HUVWLPHV-XVWLFH6WHSKHQ%UH\HUD IRUPHUODZSURIHVVRUSRVHGDPXOWLSDUWK\SRWKHWLFDO-XVWLFH5XWK%DGHU ∗ -'8QLYHUVLW\RI)ORULGD/HYLQ&ROOHJHRI/DZ%$<DOH8QLYHUVLW\)RU 0DULVDZKRMRLQHGPHRQWKLVDGYHQWXUH$OVRWKDQNVWR3URIHVVRUV6KDURQ5XVKDQG0LFKDHO 6HLJHODQGWR$QQ+RYH&DUROLQH0F&UDHDQG%HQ³=LJJ\´:LOOLDPVRQIRUWKHLUFORVHUHDGLQJRI WKLV1RWH 6&W 6HH7UDQVFULSWRI2UDO$UJXPHQWDW0RUVH6&W 1R .(9,10(5,'$ 0,&+$(/$)/(7&+(56835(0(',6&20)2577+(',9,'('628/2) &/$5(1&(7+20$6 +HDU5HFRUGLQJRI2UDO$UJXPHQWRQ0DU0RUVH6&W 1R DYDLODEOHDWKWWSZZZR\H]RUJFDVHVBBDUJXPHQW ,G ,GVHH0LFKDHO'R\OH:LUH6HUYLFH5HSRUW7UDQVFULSWV*LYHD*OLPSVHLQWR0DQ\ -XVWLFHV¶ 3HUVRQDOLWLHV 0&&/$7&+< 1(:63$3(56 0D\ DYDLODEOH DW :/15 GHVFULELQJ -XVWLFH %UH\HU DV ³SDLQIXOO\ SURIHVVRULDO´ DQG ³WKH PRVW YHUERVH RI WKH 612 FLORIDA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61 Ginsburg, a civil procedure scholar, asked about a key detail in the record;7 Justice Antonin Scalia’s rejoinders drew laughs from the audience.8 The Court wrestled during the argument with the reach of a student’s First Amendment right to unfurl a banner at a school-sponsored, off- campus event.9 Yet, during the hour-long exchange, no Justice questioned the basic premise that students retain some First Amendment rights at school.10 However, when the Court issued its opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas in a concurrence announced an extraordinary position: that the First Amendment does not apply at all to students.11 He wrote that the Court should overrule the leading precedent, Tinker v. -

Justice George Sutherland and Economic Liberty: Constitutional Conservatism and the Problem of Factions

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 6 (1997-1998) Issue 1 Article 2 December 1997 Justice George Sutherland and Economic Liberty: Constitutional Conservatism and the Problem of Factions Samuel R. Olken Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Repository Citation Samuel R. Olken, Justice George Sutherland and Economic Liberty: Constitutional Conservatism and the Problem of Factions, 6 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 1 (1997), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol6/iss1/2 Copyright c 1997 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj .WILLIAM & MARY BILL OF RIGHTS JOURNAL VOLUME 6 WINTER 1997 ISSUE 1 JUSTICE GEORGE SUTHERLAND AND ECONOMIC LIBERTY: CONSTITUTIONAL CONSERVATISM AND THE PROBLEM OF FACTIONS Samuel R. Olken* Most scholars have viewed Justice George Sutherland as a conserva- tive jurist who opposed government regulation because of his adherence to laissez-faire economics and Social Darwinism, or because of his devo- tion to natural rights. In this Article, Professor Olken analyzes these widely held misperceptions of Justice Sutherland's economic liberty jurisprudence, which was based not on socio-economic theory, but on historical experience and common law. Justice Sutherland, consistent with the judicial conservatism of the Lochner era, wanted to protect individual rights from the whims of polit- ical factions and changing democratic majorities. The Lochner era dif- ferentiation between government regulations enacted for the public wel- fare and those for the benefit of certain groups illuminates this underly- ing tenet of Justice Sutherland's jurisprudence. -

Federal Law Enforcement Officers, 1993

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin December 1994, NCJ-151166 Federal Law Enforcement Officers, 1993 By Brian A. Reaves, Ph.D. officers worked for the FBI, which FBI agents accounted for about a BJS Statistician employed 10,075 agents; the Federal fourth of Federal officers classified Bureau of Prisons (BOP), which had in the criminal investigation and en- As of December 1993, Federal agen- 9,984 correctional officers; or the Im- forcement category. Nearly all of the cies employed about 69,000 full-time migration and Naturalization Service 10,075 FBI agents nationwide were personnel authorized to make arrests (INS), which reported 9,466 officers included in this category. These Fed- and carry firearms, according to data as of December 1993. eral officers have broad investigative provided by the agencies in response to a survey conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Highlights The survey's count of officers included Of about 69,000 Federal officers employed full time in December 1993: all personnel with Federal arrest 40,002 performed duties related to criminal authority who were also authorized 58% (but not necessarily required) to carry investigation and enforcement firearms in the performance of their 11,073 worked in corrections, mostly as 16% official duties. Supervisory personnel correctional officers in Federal prisons were included. The classification of of- 7,127 performed duties primarily ficers by job function was provided by related to police response and patrol 10% the responding agencies. 5,852 performed duties related to court 9% operations The survey did not include police offi- cers, criminal investigators, and other 3,945 had security and protection 6% law enforcement personnel of the U.S. -

Mdl-875): Black Hole Or New Paradigm?

THE FEDERAL ASBESTOS PRODUCT LIABLITY MULTIDISTRICT LITIGATION (MDL-875): BLACK HOLE OR NEW PARADIGM? Hon. Eduardo C. Robreno*+ I. The Black Hole ..................................................................... 101 A. What is Asbestos? ........................................................... 101 B. How Did the Asbestos "Health Crisis" Arise? ................ 102 C. What Have Been the Medical Consequences? ................ 103 D. What Have Been the Legal Consequences? .................... 105 E. The Federal Courts' Response to the Crisis ..................... 107 1. Individual Courts' Efforts ............................................. 107 a. Standard Pretrial and Trial Management ................. 107 b. Consolidation ........................................................... 108 c. Class Actions ............................................................ 109 d. Collateral Estoppel ................................................... 110 * The author was sworn in as a United States District Judge in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania on July 27, 1992. Judge Robreno has presided over the Federal Asbestos Multidistrict Litigation MDL-875 since October 2008. + Over the past five years that I have presided over MDL-875, the court has been the beneficiary of substantial assistance by judicial and non-judicial personnel in the adjudication and administration of thousands of cases. Among those whose assistance has been extremely valuable are: District Court Judges Lowell A. Reed and Mitchell S. Goldberg; Magistrate Judges Thomas