Nicorette Monograph INHALER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smoking Cessationreview Smoking Cessation YEARS Research Review MAKING EDUCATION EASY SINCE 2006

RESEARCH Smoking CessationREVIEW Smoking Cessation YEARS Research Review MAKING EDUCATION EASY SINCE 2006 Making Education Easy Issue 24 – 2016 In this issue: Welcome to issue 24 of Smoking Cessation Research Review. Encouraging findings suggest that varenicline may increase smoking abstinence rates in light smokers Have combustible cigarettes (5–10 cigarettes per day). However, since the study was conducted in a small cohort of predominantly White met their match? cigarette smokers, it will be interesting to see whether the results can be generalised to a larger population Supporting smokers with that is more representative of the real world. depression wanting to quit Computer-generated counselling letters that target smoking reduction effectively promote future cessation, Helping smokers quit after report European researchers. Their study enrolled smokers who did not intend to quit within the next diagnosis of a potentially 6 months. At the end of this 24-month investigation, 6-month prolonged abstinence was significantly higher curable cancer amongst smokers who received individually tailored letters compared with those who underwent follow-up assessments only. Preventing postpartum return to smoking We hope you enjoy the selection in this issue, and we welcome any comments or feedback. Varenicline assists smoking Kind Regards, cessation in light smokers Brent Caldwell Natalie Walker [email protected] [email protected] Novel pMDI doubles smoking quit rates Progress towards the Smokefree 2025 goal: too slow Independent commentary by Dr Brent Caldwell. Brent Caldwell was a Senior Research Fellow at Wellington Asthma Research Group, and worked on UK data show e-cigarettes are the Inhale Study. His main research interest is in identifying and testing improved smoking cessation linked to successful quitting methods, with a particular focus on clinical trials of new smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. -

Healthy Mouth, Healthy You the Connection Between Oral and Overall Health

Healthy Mouth, Healthy You The connection between oral and overall health Your dental health is part of a bigger picture: whole-body wellness. Learn more about the relationship between your teeth, gums and the rest of your body. We keep you smiling® deltadentalins.com/enrollees Pregnancy Pregnancy is a crucial time to take care of your oral health. Hormonal changes may increase the risk of gingivitis, or inflammation of the gums. Symptoms include tenderness, swelling and bleeding of the gums. Without proper care, these problems may become more serious and can lead to gum disease. Gum disease is linked to premature birth and low birth weight. If you notice any changes in your mouth during pregnancy, see your dentist. WHAT YOU CAN DO • Be vigilant about your oral health. Brush twice daily and floss at least once a day — these basic oral health practices will help reduce plaque buildup and keep your mouth healthy. • Talk to your dentist. Always let your dentist know that you are pregnant. • Eat well. Choose nutritious, well-balanced meals, including fresh fruits, raw vegetables and dairy products. Athletics Sports and exercise are great ways to build muscle and improve cardiovascular health, but they can also increase risks to your oral health. Intense exercise can dry out the mouth, leading to a greater chance of tooth decay. If you play a high-impact sport without proper protection, you risk knocking out a tooth or dislocating your jaw. WHAT YOU CAN DO • Hydrate early. Prevent dehydration by drinking water during your workout — and several hours beforehand. • Skip the sports drinks. -

July 2021 L.A. Care Health Plan Medi-Cal Dual Formulary

L.A. Care Health Plan Medi-Cal Dual Formulary Formulary is subject to change. All previous versions of the formulary are no longer in effect. You can view the most current drug list by going to our website at http://www.lacare.org/members/getting-care/pharmacy-services For more details on available health care services, visit our website: http://www.lacare.org/members/welcome-la-care/member-documents/medi-cal LA1308E 02/20 EN lacare.org Last Updated: 07/01/2021 INTRODUCTION Foreword Te L.A. Care Health Plan (L.A. Care) Medi-Cal Dual formulary is a preferred list of covered drugs, approved by the L.A. Care Health Plan Pharmacy Quality Oversight Committee. Tis formulary applies only to outpatient drugs and self-administered drugs not covered by your Medicare Prescription Drug Beneft. It does not apply to medications used in the inpatient setting or medical ofces. Te formulary is a continually reviewed and revised list of preferred drugs based on safety, clinical efcacy, and cost-efectiveness. Te formulary is updated on a monthly basis and is efective the frst of every month. Tese updates may include, and are not limited to, the following: (i) removal of drugs and/or dosage forms, (ii) changes in tier placement of a drug that results in an increase in cost sharing, and (iii) any changes of utilization management restrictions, including any additions of these restrictions. Updated documents are available online at: lacare.org/members/getting-care/pharmacy-services. If you have questions about your pharmacy coverage, call Customer Solutions Center at 1-888-839-9909 (TTY 711), available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. -

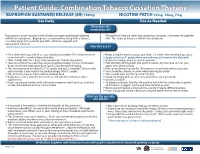

Bupropion + Patch

Patient Guide: Combination Tobacco Cessation Therapy BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150mg NICOTINE PATCH 21mg, 14mg, 7mg Use Daily Use As Needed What does this medication do? Bupropion is a non-nicotine aid that helps you quit smoking by reducing The patch will release small, but continuous amounts of nicotine through the withdrawal symptoms. Bupropion is recommended along with a tobacco skin. This helps to decrease withdrawal symptoms. cessation program to provide you with additional support and educational materials. How do I use it? BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150mg NICOTINE PATCH 21mg, 14mg, 7mg Set a date when you intend to stop smoking (quit date). The medicine needs Begin using the patch on your quit date, 1-2 weeks after starting bupropion. to be started 1-2 weeks before that date. Apply only one (1) patch when you wake up and remove the old patch. Take 1 tablet daily for 3 days, then increase to 1 tablet twice daily. If you miss a dose, use it as soon as you can. Take at a similar time each day, allowing approximately 8 hours in between Peel the back off the patch and put it on clean, dry, hair-free skin on your doses. Don’t take bupropion past 5pm to avoid trouble sleeping. upper arm, chest or back. This medicine may be taken for 7-12 weeks and up to 6 months. Discuss with Press patch firmly in place for 10 seconds so it will stick well to your skin. your provider if you need to be treated longer than 12 weeks. -

Use of Non Cigarette Tobacco Products (NCTP) Smokeless

Non Cigarette Tobacco Products (NCTP) and Electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) Michael V. Burke EdD Asst: Professor of Medicine Nicotine Dependence Center Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN Email: [email protected] ©2011 MFMER | slide-1 Goals & Objectives • Review NCTP definitions & products • Discuss prevalence/trends of NCTP • Discuss NCTP and addiction • Review recommended treatments for NCTP ©2011 MFMER | slide-2 NCTP Definitions & Products ©2011 MFMER | slide-3 Pipes ©2011 MFMER | slide-4 Cigars Images from www.trinketsandtrash.org ©2011 MFMER | slide-5 Cigar Definition U.S. Department of Treasury (1996): Cigar “Any roll of tobacco wrapped in leaf tobacco or any substance containing tobacco.” vs. Cigarette “Any roll of tobacco wrapped in paper or in any substance not containing tobacco.” ©2011 MFMER | slide-6 NCI Monograph 9. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends. ©2011 MFMER | slide-7 ©2011 MFMER | slide-8 Smokeless Tobacco Chewing tobacco • Loose leaf (i.e., Redman) • Plugs • Twists Snuff • Moist (i.e., Copenhagen, Skoal) • Dry (i.e., Honest, Honey bee, Navy, Square) ©2011 MFMER | slide-9 “Chewing Tobacco” = Cut tobacco leaves ©2011 MFMER | slide-10 “Snuff” = Moist ground tobacco ©2011 MFMER | slide-11 Type of ST Used in U.S. Chewing Tobacco Snuff National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) ©2011 MFMER | slide-12 “Spitless Tobacco” – Star Scientific ©2011 MFMER | slide-13 RJ Reynold’s ©2011 MFMER | slide-14 “Swedish Style” ST ©2011 MFMER | slide-15 Phillip Morris (Altria) ©2011 MFMER | slide-16 New Product: “Fully Dissolvables” ©2011 MFMER -

Transdermal Nicotine Maintenance Attenuates the Subjective And

Neuropsychopharmacology (2004) 29, 991–1003 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/04 $25.00 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Transdermal Nicotine Maintenance Attenuates the Subjective and Reinforcing Effects of Intravenous Nicotine, but not Cocaine or Caffeine, in Cigarette-Smoking Stimulant Abusers 1 1 ,1,2 Bai-Fang X Sobel , Stacey C Sigmon and Roland R Griffiths* 1Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; 2Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA The effects of transdermal nicotine maintenance on the subjective, reinforcing, and cardiovascular effects of intravenously administered cocaine, caffeine, and nicotine were examined using double-blind procedures in nine volunteers with histories of using tobacco, caffeine, and cocaine. Each participant was exposed to two chronic drug maintenance phases (21 mg/day nicotine transdermal patch and placebo transdermal patch). Within each drug phase, the participant received intravenous injections of placebo, cocaine (15 and 30 mg/70 kg), caffeine (200 and 400 mg/70 kg), and nicotine (1.0 and 2.0 mg/70 kg) in mixed order across days. Subjective and cardiovascular data were collected before and repeatedly after drug or placebo injection. Reinforcing effects were also assessed after each injection with a Drug vs Money Multiple-Choice Form. Intravenous cocaine produced robust dose-related increases in subjective and reinforcing effects; these effects were not altered by nicotine maintenance. Intravenous caffeine produced elevations on several subjective ratings; nicotine maintenance did not affect these ratings. Under the placebo maintenance condition, intravenous nicotine produced robust dose-related subjective effects, with maximal increases similar to the high dose of cocaine; nicotine maintenance significantly decreased the subjective and reinforcing effects of intravenous nicotine. -

Instructions for Using the Nicotine Patch Please Read These Instructions BEFORE Using the Patch

Updated 2013 Instructions for using the nicotine patch Please read these instructions BEFORE using the patch. CONGRATULATIONS! You’ve decided to use the NICOTINE PATCH to help you quit smoking. Here is your free two-week supply of patches. HOW DOES THE NICOTINE PATCH WORK? Nicotine is the chemical in tobacco that makes you crave cigarettes. The nicotine patch gives your body a steady dose of nicotine, without the harmful effects of tobacco smoke. The patch helps lessen your craving for cigarettes while you get used to not smoking. Using the patch doubles your chances of quitting for good! HOW DO I GET STARTED? Choose a day to stop all smoking. This is your Quit Date! CAN I SMOKE WHILE I’M ON THE PATCH? No! Smoking while using the patch is dangerous. DO NOT SMOKE while using the patch. IS THERE ANY REASON I SHOULD NOT USE THE PATCH? The nicotine patch is not for everyone. Check with your health care provider to see if the nicotine patch is safe for you if: • you have had a recent heart attack • you have had an allergic reaction to the patch in the past • you take insulin • you are nursing, pregnant or trying to get pregnant • you are under 18, or smoke less than 10 cigarettes a day • you have been told by a doctor not to use the patch Do not use the nicotine patch if you have been told by a doctor not to use it. (Please turn over for more instructions) New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services ARE THERE SIDE EFFECTS OF THE PATCH THAT I SHOULD WATCH FOR? Stop using the patch and call your health care provider if you get: • A rash, swelling of the skin, or skin redness that does not go away in 4 days • Rapid or irregular heartbeat • Upset stomach, vomiting, dizziness or weakness HOW DO I USE THE PATCH? Start on your Quit Date. -

Nicotine Transdermal System 21 Mg Delivered Over 24 Hours PATCH STOP SMOKING AID 21Mg STEP 1

Nicotine Transdermal System 21 mg delivered over 24 hours PATCH STOP SMOKING AID 21mg STEP 1 8 DO NOT OPEN POUCH UNTIL READY TO USE. DIRECTIONS: Apply one patch to a dry, clean, hairless portion of upper body or arms. Refer to Self-Help Guide for detailed directions. DO NOT CUT PATCH. KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN AND PETS. Used patches have enough nicotine to poison children and pets. If swallowed, get medical help or contact a Poison Control Center right away. Save pouch to use for patch disposal. Dispose of the used patch by folding sticky TO OPEN CUT ALONG DOTTED LINE 43598-448-71 ends together and putting in pouch. Store at 20-25˚C (68-77˚F). 3 DO NOT USE IF INDIVIDUAL POUCH IS OPEN OR TORN, OR IF PATCH IS CUT. Distributed by: ¢ Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc. Princeton, NJ 08540 EXP LOT 300024595 Final CLabels rton or Container Labels U/AU/A Pg. Pg 15 2 U/A Pg. 5 Pg. U/A Labeling Final TO INCREASE YOUR SUCCESS IN QUITTING: 1. You must be motivated to quit. 2. Use one patch daily according to directions. 3. It is important to complete treatment. 4. If you feel you need to use the patch for a longer period to keep from smoking, talk to your health care provider. 5. Use patch with a behavioral support program, such as the one described in the enclosed booklet. NDC XXXXX-XXX-XX Nicotine Transdermal System 21 mg delivered over 24 hours PATCH STOP SMOKING AID 21 mg Includes: Behavior Support Program with self-help guide IF YOU SMOKE MORE THAN 10 CIGARETTES PER DAY: START WITH STEP 1 IF YOU SMOKE 10 OR LESS CIGARETTES PER DAY: START WITH STEP 2 The full course for STEP 1 is 28 patches 2 (4 weeks), this package contains 2 patches only. -

Nicotine Microaerosol Inhaler

Color profile: _DEFAULT.CCM - Generic CMYK Black 150 lpi at 45 degrees ORIGINAL RESEARCH Nicotine microaerosol inhaler 3 Paul G Andrus MD1, Rod Rhem BSc1,2, Jack Rosenfeld PhD , Myrna B Dolovich PEng1,2 1Aerosol Research Laboratory and 2Departments of Medicine, and 3Pathology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario PG Andrus, R Rhem, J Rosenfeld, MB Dolovich. Nicotine Inhalateur de nicotine microaerosol inhaler. Can Respir J 1999;6(6):509-512. en microaérosol OBJECTIVE: To measure the droplet size distribution of a OBJECTIF : Mesurer la distribution de la taille des gouttelet- nicotine pressurized metered-dose inhaler using a nicotine in tes d’un aérosol-doseur sous pression contenant de la nicotine ethanol solution formulation with hydrofluoroalkane as pro- dans une solution d’éthanol et utilisant l’hydrofluoroalkane pellant. comme propulseur. MATERIALS AND METHODS: Sizing was performed at MATÉRIEL ET MÉTHODES : La détermination de la taille room temperature by multistage liquid impinger and quartz a été réalisée à la température ambiante par un impacteur en cas- crystal impactor. cade et un impacteur piézoélectrique. RESULTS: The mass median aerodynamic diameter of the RÉSULTATS : Le diamètre aérodynamique médian de la masse nicotine aerosol produced was measured at 1.6 mm by multi- de l’aérosol de nicotine produit a été mesuré à 1,6 mm par l’im- stage liquid impinger and 1.5 mm by quartz crystal impactor. pacteur en cascade et à 1,5 mm par l’impacteur piézoélectrique. CONCLUSIONS: The inhaler formulation used produces a CONCLUSIONS : La formule utilisée dans l’inhalateur pro- microaerosol of sufficiently fine droplet size that mimics the duit un microaérosol à gouttelettes suffisamment fines qui imite puff-by-puff pulmonary arterial bolus nicotine delivery of to- chaque bouffée de nicotine délivrée au sang artériel par la fu- bacco smoke. -

High Dose Patch

Copyright #ERS Journals Ltd 1999 Eur Respir J 1999; 13: 238±246 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK ± all rights reserved ISSN 0903-1936 Higher dosage nicotine patches increase one-year smoking cessation rates: results from the European CEASE trial P. Tùnnesen*, P. Paoletti**, G. Gustavsson+, M.A. Russell#, R. Saracci1, A. Gulsvik", B. Rijcken{, U. Sawe+ , members of the Steering Committee of CEASE on behalf of the European Respiratory Society Higher dosage nicotine patches increase one-year smoking cessation rates: results from the *Dept of Pulmonary Medicine, Gentofte European CEASE trial. P. Tùnnesen, P. Paoletti, G. Gustavsson, M.A. Russell, R. Saracci, Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, **Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, Ohio, USA, +Pharmacia & A. Gulsvik, B. Rijcken, U. Sawe members of the Steering Committee of CEASE on behalf of # the European Respiratory Society. #ERS Journals Ltd 1999. Upjohn, Helsingborg, Sweden, Smoking Section, Institute of Psychiatry, University ABSTRACT: The Collaborative European Anti-Smoking Evaluation (CEASE) was a of London, London, UK, 1International European multicentre, randomized, double-blind placebo controlled smoking Agency for Research on Cancer, World cessation study. The objectives were to determine whether higher dosage and longer Health Organization, Lyon, France, "Dept duration of nicotine patch therapy would increase the success rate. of Pulmonary Medicine, Haukeland Hos- Thirty-six chest clinics enrolled a total of 3,575 smokers. Subjects were allocated to pital, Bergen, Norway, {Dept of Epidemio- one of five treatment arms: placebo and either standard or higher dose nicotine logy, University of Groningen, Groningen, patches (15 mg and 25 mg daily) each given for 8 or 22 weeks with adjunctive The Netherlands. -

E-Cigarettes & Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems

E-Cigarettes & Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems Michael V. Burke EdD Program Director Mayo Clinic Nicotine Dependence Center ©2016 MFMER | slide-‹#› Learning Objectives • At the end of the presentation the participants should be able to • Describe the history and patterns of use of ENDS • Summarize literature on health and safety concerns • Discuss current regulatory and policy status and impact on tobacco control ©2016 MFMER | slide-2 What are E-Cigarettes? ©2016 MFMER | slide-‹#› History • Current iteration developed by Chinese pharmacist ‘Hon Lik; • marketed by ‘Ruyan’ in May 2004 • ‘resembling smoke’ • However, basic idea with similar structure/function researched by Big Tobacco going back at least 50 years • First patent in US 1965 • ‘Vaping’ described in a paper in 1979 ©2016 MFMER | slide-4 “Vaping” To inhale vapor from an e-cigarette ©2016 MFMER | slide-5 Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS): Basic structure A battery-powered device that provides inhaled doses of vaporized nicotine solution (usually) along with flavorants and solvents ©2016 MFMER | slide-6 Difficulty classifying as “one product” Over 466 brands Replete with differences • 7764 unique flavors • Nicotine amounts • Cartridge capacity • Toxicants in vapor • Heating element/battery Shu-Hong Zhu, et. al, Tob. Control 2014;23:iii3-iii9 doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-05167 ©2016 MFMER | slide-7 First Generation ECs (‘cigalikes’) • Disposable • Re-chargeable with pre-filled cartridges ©2016 MFMER | slide-8 Avg. Price: ~$7 - $15 ©2016 MFMER | slide-9 Second Generation -

Mayo Clinic NDC Tobacco Dependence Treatment Medication Summary*

Mayo Clinic NDC Tobacco Dependence Treatment Medication Summary* Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) Description & Examples Pros & Cons Comments Dosing Recommendations Nicotine patch Pros Comments and limitations Dosing (24-hour patch) Achieve desired levels of replacement Patches vary in strengths and the length of time (OTC) over which nicotine is delivered. Depending on >40 cpd = 42 mg per day Easy to use Only needs to be applied once a day the brand of patch used, may be left on for 21-39 cpd = 28-35 mg per day 24-hour delivery systems: anywhere from 16 to 24 hours. Patches may be 10-20 cpd = 14-21 mg per day 21, 14, 7 mg/24 hour Few side effects placed anywhere on the upper body, including <10 cpd = 14 mg per day Cons Less flexible dosing arms and back. Rotate the patch site each time a 16-hour delivery systems: new patch is applied. If a dose > 42mg per day may be indicated, 15, 10, 5 mg/16 hour Slower onset of delivery contact the patient’s prescriber. Adjust based on Mild skin rashes and irritation May purchase without a prescription. withdrawal symptoms, urges, and comfort. (Generic available) After 4-6 weeks of smoking abstinence, taper every 2-4 weeks in 7-14 mg steps as tolerated. Nicotine lozenge Pros Comments or limitations Dosing as monotherapy Easy to use Use at least 8-9 lozenges per day initially. Based on time to first cigarette of the day: Regular or “mini” size Delivers doses of nicotine approximately 25% Efficacy and frequency of side effects related to <30 minutes = 4 mg (OTC) higher than nicotine gum amount used.