Transdermal Nicotine Maintenance Attenuates the Subjective And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formulation and Evaluation of Transdermal Patch and Gel of Nateglinide

Human Journals Research Article September 2015 Vol.:4, Issue:2 © All rights are reserved by C. Aparna et al. Formulation and Evaluation of Transdermal Patch and Gel of Nateglinide Keywords: Nateglinide, transdermal patch and gel, HPMC, ethyl cellulose, carbopol, PVA, PVP ABSTRACT Anusha Gundeti, C. Aparna*, Dr. Prathima Srinivas The objective of the present work was to formulate Transdermal Drug Delivery systems of Nateglinide, an Department of Pharmaceutics, Sri Venkateshwara antidiabetic drug belonging to meglitinide class with a half life of 1.5 hrs. Transdermal patches containing nateglinide were College of Pharmacy, prepared by solvent casting method using the combinations Affiliated to Osmania University, of HPMC:EC, PVA:PVP, HPMC:Eudragit RS 100, Eudragit RL100:RS100 in different proportions and by incorporating Madhapur, Hyderabad, Telangana -500081, India. different permeation enhancers (polyethylene glycol 400, Su bmission: 7 September 2015 DMSO). The transdermal patches were evaluated for their physicochemical properties like thickness, weight variation, Accepted: 11 September 2015 folding endurance, percentage moisture absorption, percentage Published: 25 September 2015 moisture loss, in-vitro diffusion studies & ex-vivo permeation studies. Transdermal Gel was formulated using HPMC, carbopol 934, carbopol 940 and methyl cellulose. Gels were evaluated for homogeneity, pH, viscosity, drug content, in-vitro diffusion studies & ex-vivo permeation studies. By comparing the drug release F5 (HPMC:EC) formulation was selected as optimized formulation as it could sustain the drug release for 12 hrs i.e. 99.2% when compared to gel. Stability studies were www.ijppr.humanjournals.com carried out according to ICH guidelines and the patches maintained integrity and good physicochemical properties during the study period. -

Smoking Cessationreview Smoking Cessation YEARS Research Review MAKING EDUCATION EASY SINCE 2006

RESEARCH Smoking CessationREVIEW Smoking Cessation YEARS Research Review MAKING EDUCATION EASY SINCE 2006 Making Education Easy Issue 24 – 2016 In this issue: Welcome to issue 24 of Smoking Cessation Research Review. Encouraging findings suggest that varenicline may increase smoking abstinence rates in light smokers Have combustible cigarettes (5–10 cigarettes per day). However, since the study was conducted in a small cohort of predominantly White met their match? cigarette smokers, it will be interesting to see whether the results can be generalised to a larger population Supporting smokers with that is more representative of the real world. depression wanting to quit Computer-generated counselling letters that target smoking reduction effectively promote future cessation, Helping smokers quit after report European researchers. Their study enrolled smokers who did not intend to quit within the next diagnosis of a potentially 6 months. At the end of this 24-month investigation, 6-month prolonged abstinence was significantly higher curable cancer amongst smokers who received individually tailored letters compared with those who underwent follow-up assessments only. Preventing postpartum return to smoking We hope you enjoy the selection in this issue, and we welcome any comments or feedback. Varenicline assists smoking Kind Regards, cessation in light smokers Brent Caldwell Natalie Walker [email protected] [email protected] Novel pMDI doubles smoking quit rates Progress towards the Smokefree 2025 goal: too slow Independent commentary by Dr Brent Caldwell. Brent Caldwell was a Senior Research Fellow at Wellington Asthma Research Group, and worked on UK data show e-cigarettes are the Inhale Study. His main research interest is in identifying and testing improved smoking cessation linked to successful quitting methods, with a particular focus on clinical trials of new smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. -

Drug Information Center Highlights of FDA Activities

Drug Information Center Highlights of FDA Activities – 9/1/20 – 9/30/20 FDA Drug Safety Communications & Drug Information Updates: Efficacy & Safety Concerns for Atezolizumab in Combination with Paclitaxel 9/8/20 The FDA alerted health care professionals and patients that a clinical trial evaluating atezolizumab plus paclitaxel in patients with previously untreated inoperable locally advanced or metastatic triple negative breast cancer that the drug combination was not effective. The combination of atezolizumab with another paclitaxel formulation, paclitaxel protein‐bound, is currently approved for use in adult patients with metastatic triple negative breast cancer, but this continued approval may be contingent on the results of additional studies. Paclitaxel should NOT be used as a replacement for paclitaxel protein bound in clinical practice. Electronic Expanded Access Requests 9/23/20 The FDA announced that the Reagan‐Udall Foundation has launched Expanded Access eRequest, a tool to submit expanded access requests for individual patient expanded access for drugs and biologics in non‐emergency settings. The tool allows auto population of forms, uploading of relevant documents, links to resources for physicians, patients, and caregivers, and secure application submission to the FDA. Benzodiazepine Drug Class: Drug Safety Communication ‐ Boxed Warning Update 9/23/20 The FDA is requiring the Boxed Warning be updated for all benzodiazepines to address serious risks of abuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal across the medication class. Changes are also being incorporated in the Medication Guides, and other sections of the prescribing information including the Warnings and Precautions, Drug Abuse and Dependence, and Patient Counseling Information sections. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl): Serious Problems with High Doses 9/24/20 The FDA issued a warning that taking higher than recommended doses of the common OTC allergy medication diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can lead to serious heart problems, seizures, coma, or even death. -

Mcneil Consumer : Mdl No

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA IN RE: MCNEIL CONSUMER : MDL NO. 2190 HEALTHCARE, ET AL., MARKETING : AND SALES PRACTICES LITIGATION : : Applies to: : ALL ACTIONS : MEMORANDUM McLaughlin, J. July 13, 2012 This multidistrict litigation arises out of quality control problems at the defendants’ facility manufacturing over- the-counter healthcare products in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, which led to a series of recalls of those products. The named plaintiffs assert claims for economic loss on behalf of a putative nationwide class against Johnson & Johnson (“J&J”), McNeil Consumer Healthcare (“McNeil”), and four of their executives. The plaintiffs allege that they overpaid for the defendants’ products as a result of the recalls and the defendants’ scheme to conceal or downplay the scope of the quality control problems. The defendants, who have offered a coupon or cash refund to consumers who purchased recalled drugs, have moved to dismiss the operative complaint, and assert that the named plaintiffs lack constitutional standing and have not met the applicable pleading standard. The Court will grant the defendants’ motion because the plaintiffs have not pled facts that show a cognizable injury in fact, which is required to confer Article III standing. I. Procedural Background This litigation resulted from the consolidation of ten individual actions filed around the country. Haviland v. McNeil Consumer Healthcare, No. 10-2195, was filed in this Court on May 12, 2010, asserting economic injuries arising out of the April 30, 2010 recall of over-the-counter children’s drugs by McNeil, a part of the J&J “Family of Companies.” Eight additional cases, also arising out of the April 2010 recall, were filed in district courts around the country.1 All cases asserted claims for economic injury only, with the exception of Rivera v. -

Approved Prenatal Medications Pain Medications • Tylenol

Approved Prenatal Medications Pain Medications Tylenol (acetaminophen) for minor aches and pains, headaches. (Do not use: Aspirin, Motrin, Advil, Aleve, Ibuprofen.) Coughs/Colds Robitussin (Cough) Robitussin DM (non-productive cough) DO NOT USE TILL OVER 12 WEEKS Secrets and Vicks Throat Lozenges Mucinex Sore Throat Chloraseptic spray Saline Gargle Sucrets and Vicks Throat Lozenges Antihistamines/Allergies Zyrtec Claritin Benadryl Dimetapp Insomnia Benadryl Unison Hemorrhoids Preparation H Tucks Anusol Diarrhea Imodium (1-2 doses- if it persists please notify the office) BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast) Lice RID (only!) DO NOT USE Kwell Itching Benadryl Calamine or Caladryl Lotion Hydrocortisone cream Heartburn, Indigestion, Gas Tums Gas-X Mylanta Pepcid Maalox Zantac *DO NOT USE PEPTO BISMOL- it contains aspirin Decongestants Sudafed Robitussin CF- Only if over 12 weeks Tavist D Ocean Mist Nasal Spray (saline solutions) Nausea Small Frequent Meals Ginger Ale Vitamin B6 Sea Bands Yeast Infections Monistat Mycolog Gyne-lotrimin Toothache Orajel May see dentists, have cavity filled using Novocain or lidocaine, have x-rays with double lead shield, may have antibiotics in the Penicillin family (penicillin, amoxicillin) Sweetners- all should be consumed in moderation with water being consumed more frequently Nutrisweet (aspartame) Equal (aspartame) Splenda (sucralose) Sweet’n Low (saccharin) *note avoid aspartame if you have phenylketonuria (PKU) Constipation Colace Fibercon Citrucel Senokot Metamucil Milk of Magnesia Fiberall Miralax Eczema Hydrocortisone Cream Medications to AVOID Accurate Lithium Paxil Ciprofloxacin Tetracycline Coumadin Other Chemicals to AVOID Cigarettes Alcohol Recreational Drugs: marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy, heroin . -

Healthy Mouth, Healthy You the Connection Between Oral and Overall Health

Healthy Mouth, Healthy You The connection between oral and overall health Your dental health is part of a bigger picture: whole-body wellness. Learn more about the relationship between your teeth, gums and the rest of your body. We keep you smiling® deltadentalins.com/enrollees Pregnancy Pregnancy is a crucial time to take care of your oral health. Hormonal changes may increase the risk of gingivitis, or inflammation of the gums. Symptoms include tenderness, swelling and bleeding of the gums. Without proper care, these problems may become more serious and can lead to gum disease. Gum disease is linked to premature birth and low birth weight. If you notice any changes in your mouth during pregnancy, see your dentist. WHAT YOU CAN DO • Be vigilant about your oral health. Brush twice daily and floss at least once a day — these basic oral health practices will help reduce plaque buildup and keep your mouth healthy. • Talk to your dentist. Always let your dentist know that you are pregnant. • Eat well. Choose nutritious, well-balanced meals, including fresh fruits, raw vegetables and dairy products. Athletics Sports and exercise are great ways to build muscle and improve cardiovascular health, but they can also increase risks to your oral health. Intense exercise can dry out the mouth, leading to a greater chance of tooth decay. If you play a high-impact sport without proper protection, you risk knocking out a tooth or dislocating your jaw. WHAT YOU CAN DO • Hydrate early. Prevent dehydration by drinking water during your workout — and several hours beforehand. • Skip the sports drinks. -

July 2021 L.A. Care Health Plan Medi-Cal Dual Formulary

L.A. Care Health Plan Medi-Cal Dual Formulary Formulary is subject to change. All previous versions of the formulary are no longer in effect. You can view the most current drug list by going to our website at http://www.lacare.org/members/getting-care/pharmacy-services For more details on available health care services, visit our website: http://www.lacare.org/members/welcome-la-care/member-documents/medi-cal LA1308E 02/20 EN lacare.org Last Updated: 07/01/2021 INTRODUCTION Foreword Te L.A. Care Health Plan (L.A. Care) Medi-Cal Dual formulary is a preferred list of covered drugs, approved by the L.A. Care Health Plan Pharmacy Quality Oversight Committee. Tis formulary applies only to outpatient drugs and self-administered drugs not covered by your Medicare Prescription Drug Beneft. It does not apply to medications used in the inpatient setting or medical ofces. Te formulary is a continually reviewed and revised list of preferred drugs based on safety, clinical efcacy, and cost-efectiveness. Te formulary is updated on a monthly basis and is efective the frst of every month. Tese updates may include, and are not limited to, the following: (i) removal of drugs and/or dosage forms, (ii) changes in tier placement of a drug that results in an increase in cost sharing, and (iii) any changes of utilization management restrictions, including any additions of these restrictions. Updated documents are available online at: lacare.org/members/getting-care/pharmacy-services. If you have questions about your pharmacy coverage, call Customer Solutions Center at 1-888-839-9909 (TTY 711), available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. -

Over-The-Counter (OTC) Medications Applies To: Tufts Health Ritogether and Tufts Health Together*

Over-the-Counter (OTC) Medications Applies to: Tufts Health RITogether and Tufts Health Together* As communicated in the November 1, 2018 Provider Update, the following changes are effective for fill dates on or after January 1, 2019. As a result of this change, some OTC medications will require prior authorization in certain circumstances as outlined below: Brand-Name OTC Medication Has a Covered Interchangeable Generic Version Available Afrin No Drip Advil capsule Advil tablet Advil PM tablet Afrin Nasal Spray Original nasal solution Afrin No Drip Aveeno Oatmeal Severe nasal Aleve tablet Baciguent ointment Benadryl capsule Bath Pak Treatment solution Benadryl Allergy Benadryl Allergy Benadryl Allergy Benadryl Extra Benefiber powder tablet capsule Liquid Strength cream Caltrate 600 +D Centrum Silver Betadine Swabstick Caltrate + D tablet Centrum liquid Plus Minerals tablet tablet Centrum Silver Centrum Ultra Men’s Children’s Advil Centrum tablet Cheracol-D syrup Adult 50+ tablet tablet suspension Children’s Benadryl Citracal Calcium + Children’s Benadryl Children’s Tylenol Chlor-Trimeton Allergy chewable D Slow Release Allergy liquid suspension syrup tablet tablet Citrucel Fiber Claritin-D 12 hour Claritin-D 24 hour Clear Cough Liquid Citrucel tablet Laxative powder tablet tablet PM Dimetapp DM Dex4 Fast Acting Dimetapp Cold and Colace capsule Conceptrol 4% gel Cough and Cold Glucose liquid Allergy elixir elixir Dristan nasal spray Dulcolax tablet D-Vi-Sol liquid Ecotrin tablet Evac powder Ex-Lax chewable Gas-X chewable Feosol tablet -

Benadryl (Diphenhydramine) Dosing Chart

1084 Cromwell Avenue Rocky Hill, CT 06067 (860) 721-7561 – Phone (860) 721-9199 – Fax Benadryl (Diphenhydramine) Dosing Chart *Ages 6 months & above* Dose every 6 hours: Dose for hives and/or itching. In general, once hives have started, you should continue regular dosing until there have not been hives for the entire day. Benadryl (Diphenhydramine) Liquid: Chewable Tablets: Tablets: Weight: 12.5mg/5ml 12.5mg each 25 mg each 17-21 pounds ¾ tsp. (3.75ml) Use Liquid Use Liquid Use 22-32 pounds 1 tsp. (5ml) 1 tablet Liquid or Chews Use 33-42 pounds 1 ½ tsp. (7.5ml) 1 ½ tablets Liquid or Chews 43-53 pounds 2 tsp. (10ml) 2 tablets 1 tablet 54-64 pounds 2 ½ tsp. (12.5ml) 2 ½ tablets 1 tablet 65-75 pounds 3 tsp. (15ml) 3 tablets 1 tablet 76-86 pounds 3 ½ tsp. (17.5ml) 3 ½ tablets 1 tablet >86 pounds 4 tsp. (20ml) 4 tablets 2 tablets EDUCATION ON CALL Administering Medicine Safely When your child isn’t feeling well, you want to relieve their discomfort as quickly as possible. Be prepared with information that can help you understand the differences between pediatric pain relievers and fever reducers, and how to administer them safely. Always read the label 1. Active ingredient: Ingredient that makes the medicine work 2. Uses: Symptoms the medicine treats 3. Directions: The amount of medicine to give and how often Know the difference TYLENOL® MOTRIN® Active ingredient: Acetaminophen Active ingredient: Ibuprofen • Treats pain & fever • Treats pain & fever • Gentle on tummies • Lasts up to 8 hours • Dosing available from your pediatrician for • Can be used for children 6 months of age or older children 6 months and younger Never give aspirin to children. -

An Archetype Swing in Transdermal Drug Delivery

Indo American Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 2017 ISSN NO: 2231-6876 A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW ON MICRONEEDLES - AN ARCHETYPE SWING IN TRANSDERMAL DRUG DELIVERY G. Ravi*, N. Vishal Gupta, M. P. Gowrav Department of Pharmaceutics, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS University, Shri Shivarathreeshwara Nagara, Mysuru, Karnataka, India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Transdermal drug delivery is the non-invasive delivery of medications through the skin Received 23/12/2016 surface into the systemic circulation. The advantage of transdermal drug delivery system is Available online that it is painless technique of administration of drugs. The advantage of transdermal drug 31/01/2017 delivery system is that it is painless technique of administration of drugs. Transdermal drug delivery system can improve the therapeutic efficacy and safety of the drugs because drug Keywords delivered through the skin at a predetermined and controlled rate. Due to the various Microneedles, biomedical benefits, it has attracted many researches. The barrier nature of stratumcorneum Hypodermic Needles, poses a danger to the drug delivery. By using microneedles, a pathway into the human body Transdermal, can be recognized which allow transportation of macromolecular drugs such as insulin or Stratumcorneum, vaccine. These microneedles only penetrate outer layers of the skin, exterior sufficient not to Patch. reach the nerve receptors of the deeper skin. Thus the microneedles supplement is supposed painless and reduces the infection and injuries. Researches from the past few years showed that microneedles have emerged as a novel carrier and considered to be effective for safe and improved delivery of the different drugs. Microneedles development is created a new pathway in the drug delivery field. -

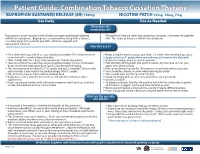

Bupropion + Patch

Patient Guide: Combination Tobacco Cessation Therapy BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150mg NICOTINE PATCH 21mg, 14mg, 7mg Use Daily Use As Needed What does this medication do? Bupropion is a non-nicotine aid that helps you quit smoking by reducing The patch will release small, but continuous amounts of nicotine through the withdrawal symptoms. Bupropion is recommended along with a tobacco skin. This helps to decrease withdrawal symptoms. cessation program to provide you with additional support and educational materials. How do I use it? BUPROPION SUSTAINED RELEASE (SR) 150mg NICOTINE PATCH 21mg, 14mg, 7mg Set a date when you intend to stop smoking (quit date). The medicine needs Begin using the patch on your quit date, 1-2 weeks after starting bupropion. to be started 1-2 weeks before that date. Apply only one (1) patch when you wake up and remove the old patch. Take 1 tablet daily for 3 days, then increase to 1 tablet twice daily. If you miss a dose, use it as soon as you can. Take at a similar time each day, allowing approximately 8 hours in between Peel the back off the patch and put it on clean, dry, hair-free skin on your doses. Don’t take bupropion past 5pm to avoid trouble sleeping. upper arm, chest or back. This medicine may be taken for 7-12 weeks and up to 6 months. Discuss with Press patch firmly in place for 10 seconds so it will stick well to your skin. your provider if you need to be treated longer than 12 weeks. -

Use of Non Cigarette Tobacco Products (NCTP) Smokeless

Non Cigarette Tobacco Products (NCTP) and Electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) Michael V. Burke EdD Asst: Professor of Medicine Nicotine Dependence Center Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN Email: [email protected] ©2011 MFMER | slide-1 Goals & Objectives • Review NCTP definitions & products • Discuss prevalence/trends of NCTP • Discuss NCTP and addiction • Review recommended treatments for NCTP ©2011 MFMER | slide-2 NCTP Definitions & Products ©2011 MFMER | slide-3 Pipes ©2011 MFMER | slide-4 Cigars Images from www.trinketsandtrash.org ©2011 MFMER | slide-5 Cigar Definition U.S. Department of Treasury (1996): Cigar “Any roll of tobacco wrapped in leaf tobacco or any substance containing tobacco.” vs. Cigarette “Any roll of tobacco wrapped in paper or in any substance not containing tobacco.” ©2011 MFMER | slide-6 NCI Monograph 9. Cigars: Health Effects and Trends. ©2011 MFMER | slide-7 ©2011 MFMER | slide-8 Smokeless Tobacco Chewing tobacco • Loose leaf (i.e., Redman) • Plugs • Twists Snuff • Moist (i.e., Copenhagen, Skoal) • Dry (i.e., Honest, Honey bee, Navy, Square) ©2011 MFMER | slide-9 “Chewing Tobacco” = Cut tobacco leaves ©2011 MFMER | slide-10 “Snuff” = Moist ground tobacco ©2011 MFMER | slide-11 Type of ST Used in U.S. Chewing Tobacco Snuff National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) ©2011 MFMER | slide-12 “Spitless Tobacco” – Star Scientific ©2011 MFMER | slide-13 RJ Reynold’s ©2011 MFMER | slide-14 “Swedish Style” ST ©2011 MFMER | slide-15 Phillip Morris (Altria) ©2011 MFMER | slide-16 New Product: “Fully Dissolvables” ©2011 MFMER