Sports Schools: an International Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's 3000M Steeplechase

Games of the XXXII Olympiad • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 3000m Steeplechase Entrants: 47 Event starts: August 1 Age (Days) Born SB PB 1003 GEGA Luiza ALB 32y 266d 1988 9:29.93 9:19.93 -19 NR Holder of all Albanian records from 800m to Marathon, plus the Steeplechase 5000 pb: 15:36.62 -19 (15:54.24 -21). 800 pb: 2:01.31 -14. 1500 pb: 4:02.63 -15. 3000 pb: 8:52.53i -17, 8:53.78 -16. 10,000 pb: 32:16.25 -21. Half Mar pb: 73:11 -17; Marathon pb: 2:35:34 -20 ht EIC 800 2011/2013; 1 Balkan 1500 2011/1500; 1 Balkan indoor 1500 2012/2013/2014/2016 & 3000 2018/2020; ht ECH 800/1500 2012; 2 WSG 1500 2013; sf WCH 1500 2013 (2015-ht); 6 WIC 1500 2014 (2016/2018-ht); 2 ECH 3000SC 2016 (2018-4); ht OLY 3000SC 2016; 5 EIC 1500 2017; 9 WCH 3000SC 2019. Coach-Taulant Stermasi Marathon (1): 1 Skopje 2020 In 2021: 1 Albanian winter 3000; 1 Albanian Cup 3000SC; 1 Albanian 3000/5000; 11 Doha Diamond 3000SC; 6 ECP 10,000; 1 ETCh 3rd League 3000SC; She was the Albanian flagbearer at the opening ceremony in Tokyo (along with weightlifter Briken Calja) 1025 CASETTA Belén ARG 26y 307d 1994 9:45.79 9:25.99 -17 Full name-Belén Adaluz Casetta South American record holder. 2017 World Championship finalist 5000 pb: 16:23.61 -16. 1500 pb: 4:19.21 -17. 10 World Youth 2011; ht WJC 2012; 1 Ibero-American 2016; ht OLY 2016; 1 South American 2017 (2013-6, 2015-3, 2019-2, 2021-3); 2 South American 5000 2017; 11 WCH 2017 (2019-ht); 3 WSG 2019 (2017-6); 3 Pan-Am Games 2019. -

THE WESTERN ALLIES' RECONSTRUCTION of GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter a Thesis Subm

SPORTING DEMOCRACY: THE WESTERN ALLIES’ RECONSTRUCTION OF GERMANY THROUGH SPORT, 1944-1952 by Heather L. Dichter A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, University of Toronto © Copyright by Heather L. Dichter, 2008 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-57981-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Bourdieusian Approach to the Career Transition Process of Dropout College Student-Athletes in South Korea

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2019 Reproduction in Athletic Education, Society, and Culture: A Bourdieusian Approach to the Career Transition Process of Dropout College Student-Athletes in South Korea Benjamin Hisung Nam University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Nam, Benjamin Hisung, "Reproduction in Athletic Education, Society, and Culture: A Bourdieusian Approach to the Career Transition Process of Dropout College Student-Athletes in South Korea. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5423 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Benjamin Hisung Nam entitled "Reproduction in Athletic Education, Society, and Culture: A Bourdieusian Approach to the Career Transition Process of Dropout College Student-Athletes in South Korea." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in -

Sports and Physical Education in China

Sport and Physical Education in China Sport and Physical Education in China contains a unique mix of material written by both native Chinese and Western scholars. Contributors have been carefully selected for their knowledge and worldwide reputation within the field, to provide the reader with a clear and broad understanding of sport and PE from the historical and contemporary perspectives which are specific to China. Topics covered include: ancient and modern history; structure, administration and finance; physical education in schools and colleges; sport for all; elite sport; sports science & medicine; and gender issues. Each chapter has a summary and a set of inspiring discussion topics. Students taking comparative sport and PE, history of sport and PE, and politics of sport courses will find this book an essential addition to their library. James Riordan is Professor and Head of the Department of Linguistic and International Studies at the University of Surrey. Robin Jones is a Lecturer in the Department of PE, Sports Science and Recreation Management, Loughborough University. Other titles available from E & FN Spon include: Sport and Physical Education in Germany ISCPES Book Series Edited by Ken Hardman and Roland Naul Ethics and Sport Mike McNamee and Jim Parry Politics, Policy and Practice in Physical Education Dawn Penney and John Evans Sociology of Leisure A reader Chas Critcher, Peter Bramham and Alan Tomlinson Sport and International Politics Edited by Pierre Arnaud and James Riordan The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Understanding Sport An introduction to the sociological and cultural analysis of sport John Home, Gary Whannel and Alan Tomlinson Journals: Journal of Sports Sciences Edited by Professor Roger Bartlett Leisure Studies The Journal of the Leisure Studies Association Edited by Dr Mike Stabler For more information about these and other titles published by E& FN Spon, please contact: The Marketing Department, E & FN Spon, 11 New Fetter Lane, London, EC4P 4EE. -

KNZB NK 2007 01 Juni 2007,18:35 Nationale Kampioenschappen Zwemmen 2007 Ranglijst Bladzijde 2 Nr. 1 400M Vrije Slag

Nationale Kampioenschappen Zwemmen 2007 Bladzijde 2 Ranglijst Nr. 1 400m vrije slag Heren Heren Senioren Open 01.06.2007 Limiet 4:31.00 Wereldrecord 2002 3:40.08 Ian Thorpe AUS Manchester Europees Record 2000 3:43.40 Massimiliano Rosolino ITA Sydney Nationaal Record 2002 3:47.20 Pieter van den Hoogenband NED Amersfoort Kampioenschapsrecord 2002 3:47.20 Pieter van den Hoogenband PSV Amersfoort Heren Jeugd 1 en 2 Jr. Afk./depot Tijd RT 1. Job Kienhuis 89 De Dinkel Denek 4:03.87 0.93 50m: 28.48 28.48 150m: 1:30.00 30.36 250m: 2:31.45 30.44 350m: 3:33.22 30.89 100m: 59.64 31.16 200m: 2:01.01 31.01 300m: 3:02.33 30.88 400m: 4:03.87 30.65 2. Jorrit Visser 89 DZ&PC 4:12.25 50m: 28.34 28.34 150m: 1:31.78 32.24 250m: 2:37.09 32.84 350m: 3:42.50 32.77 100m: 59.54 31.20 200m: 2:04.25 32.47 300m: 3:09.73 32.64 400m: 4:12.25 29.75 3. Bo Wullings 89 De Dolfijn 4:12.37 50m: 27.92 27.92 150m: 1:29.33 31.04 250m: 2:34.69 33.18 350m: 3:41.38 33.23 100m: 58.29 30.37 200m: 2:01.51 32.18 300m: 3:08.15 33.46 400m: 4:12.37 30.99 4. Ewoud Potiek 89 't Tolhekke 4:15.10 50m: 28.22 28.22 150m: 1:33.58 33.25 250m: 2:39.68 32.66 350m: 3:44.35 32.11 100m: 1:00.33 32.11 200m: 2:07.02 33.44 300m: 3:12.24 32.56 400m: 4:15.10 30.75 5. -

International Olympic Committee, Lausanne, Switzerland

A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND. WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG TEACHING VALUESVALUES AN OLYYMPICMPIC EDUCATIONEDUCATION TOOLKITTOOLKIT WWW.OLYMPIC.ORG D R O W E R O F D N A S T N E T N O C TEACHING VALUES AN OLYMPIC EDUCATION TOOLKIT A PROJECT OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC COMMITTEE, LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The International Olympic Committee wishes to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the preparation of this toolkit: Author/Editor: Deanna L. BINDER (PhD), University of Alberta, Canada Helen BROWNLEE, IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education, Australia Anne CHEVALLEY, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Charmaine CROOKS, Olympian, Canada Clement O. FASAN, University of Lagos, Nigeria Yangsheng GUO (PhD), Nagoya University of Commerce and Business, Japan Sheila HALL, Emily Carr Institute of Art, Design & Media, Canada Edward KENSINGTON, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Ioanna MASTORA, Foundation of Olympic and Sport Education, Greece Miquel de MORAGAS, Centre d’Estudis Olympics (CEO) Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Spain Roland NAUL, Willibald Gebhardt Institute & University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany Khanh NGUYEN, IOC Photo Archives, Switzerland Jan PATERSON, British Olympic Foundation, United Kingdom Tommy SITHOLE, International Olympic Committee, Switzerland Margaret TALBOT, United Kingdom Association of Physical Education, United Kingdom IOC Commission for Culture & Olympic Education For Permission to use previously published or copyrighted -

2021 European Indoor Championships Statistics – Men PV

2021 European Indoor Championships Statistics – Men PV by KKenNakamura Summary Page: All time performance list at the European Indoor Championships Performance Performer Height Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 6.04 Renaud Lavillenie FRA 1 Praha 20 15 2 6.03 Ren aud Lavillenie 1 Paris 2011 3 6.01 Renaud Lavillenie 1 Göteborg 2013 4 2 5.90 Pyotr Bochkaryov RUS 1 Paris 1994 4 2 5.90 Igor Pavlov RUS 1 Madrid 2005 4 2 5.90 Pawel Wojciechowski POL 1 Glasgow 2019 Margin of Victory Differe nce Height Name Nat Venue Year Max 27cm 6.03m Renaud Lavillenie FRA Paris 2011 25cm 6.01m Renaud Lavillenie FRA Göteborg 2013 Min 0cm 5.40 Wolfgang Nordwig GDR Grenoble 1972 5.60 Konstantin Volkov URS Sindelfingen 1980 5.60 Vladimir Polyakov URS Budapest 1983 5.70 Sergey Bubka URS Piraeus 1985 5.70 Atanas Tarev BUL Madrid 1986 5.85 Thierry Vigneron FRA Lievin 1987 5.75 Grigoriy Yegorov URS Den Haag 1989 5.80 Tim Lobinger GER Valencia 1998 5.75 Tim Lobinger GER Wien 2002 5.85 Piotr Lisek POL Beograd 2017 Best Marks for Places in the European Indoor Championships Po s Height Name Nat Venue Year 1 6.04 Renaud Lavillenie FR A Praha 20 15 6.03 Renaud Lavillenie FRA Paris 2011 2 5.85 Ferenc Salbert FRA Lieven 1987 Aleksandr Gripich RUS Praha 2015 Konstadinos Filippidis GRE Beograd 2017 Pio tr Lisek POL Glasgow 2019 3 5.85 Piotr Lisek POL Praha 2015 Pawel Wojciechowski POL Beograd 2017 Highest vault in each round at European Indoor Championships Round Heigh t Name Nat Position Venue Year Final 6.03 Renaud Lavillenie FRA 1 Paris 2011 First round 5.70 Artem Kuptsov RUS 1qA Madrid 2005 Lavillenie, Gripich, Lisek et.al. -

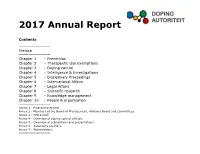

2017 Annual Report

2017 Annual Report Contents -------------------------- Preface -------------------------- Chapter 1 – Prevention Chapter 2 – Therapeutic Use Exemptions Chapter 3 – Doping control Chapter 4 – Intelligence & Investigations Chapter 5 – Disciplinary Proceedings Chapter 6 – International Affairs Chapter 7 – Legal Affairs Chapter 8 – Scientific research Chapter 9 – Knowledge management Chapter 10 – People & organisation -------------------------- Annex 1 - Financial overview Annex 2 - Members of the Board of Management, Advisory Board and Committees Annex 3 - Office staff Annex 4 - Overview of doping control officials Annex 5 - Overview of publications and presentations Annex 6 - Secondary positions Annex 7 - Abbreviations -------------------------- Preface You are viewing the twelfth Annual Report from the Anti-Doping Authority of the Netherlands. This is the seventh Annual Report to be published exclusively in digital form. 2017 was the year in which the lion's share of the project 'Together for clean sport' (SVESS) was implemented. This project is being carried out in close cooperation with NOC*NSF, the KNVB, the KNBB, the Athletics Union and Fit!vak. The Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport is also providing financial support for the project. There are various activities (prevention and control) targeting football, billiards, athletics and fitness. The aim is to establish models tailored specifically to team sports, sports with a high percentage of inadvertent doping violations, sports with a relatively high doping risk, and fitness. The models will be used by other sports associations and organisations in these categories to improve their anti-doping policies. Given the ongoing intensive contacts with the press in 2017, it would seem fair to conclude that the strong profile of the Doping Authority is a fact of life that does not depend on the seriousness or extent of current doping cases. -

2007 World Stars Artistic Gymnastics World Cup Cat. a Moscow (RUS) 2007 May 25-26

2007 World Stars Artistic Gymnastics World Cup Cat. A Moscow (RUS) 2007 May 25-26 Men’s Floor Exercise Final 2007 May 26 2007 World Stars Moscow (RUS) Score Men’s Floor Exercise Final 1 Anton Golotsutskov RUS 15.650 2 Wajdi Bouallegue TUN 15.550 3 Alexander Shatilov ISR 15.350 4 Yevgeny Spiridonov GER 15.300 5 Filip Ude CRO 15.250 6 Isaac Botella ESP 15.100 7 Gael da Silva FRA 14.950 8 Enrico Pozzo ITA 14.600 Men’s Pommel Horse Final 2007 May 26 2007 World Stars Moscow (RUS) Score Men’s Pommel Horse Final 1 Zhang Hongtao CHN 16.100 2 Daniel Popescu ROU 15.600 3 Dmitry Vasilyev RUS 15.350 4 Louis Smith GBR 15.150 5 Nikolai Kryukov RUS 14.800 6 Maxim Petrishko KAZ 13.950 7 Jose Luis Fuentes VEN 13.850 8 Sid Ali Ferdsani ALG 12.650 Men’s Rings Final 2007 May 26 2007 World Stars Moscow (RUS) Score Men’s Rings Final 1 Yan Ming CHN 16.400 2 Yuri van Gelder NED 16.300 3 Regulo Carmona VEN 16.300 4 Timur Kurbanbayev KAZ 16.300 5 Konstantin Pluzhnikov RUS 16.250 6 Alexander Safoshkin RUS 16.150 7 Alexander Vorobyov UKR 16.150 8 Matteo Angioletti ITA 15.700 Men’s Vault Final 2007 May 26 2007 World Stars Moscow (RUS) Final Men’s Vault Final 1 Lezsek Blanik POL 16.450 2 Jeffrey Wammes NED 16.175 3 Anton Golotsutskov RUS 16.100 4 Daniel Popescu ROU 16.100 5 Isaac Botella ESP 16.000 6 Wai Hung Shek TPE 15.650 7 Filip Ude CRO 15.225 8 Mohammed Ali Alasi Ali JOR 7.175 Men’s Parallel Bars Final 2007 May 26 2007 World Stars Moscow (RUS) Score Men’s Parallel Bars Final 1 Yann Cucherat FRA 16.200 2 Mitja Petkovsek SLO 16.100 3 Roman Zozulya UKR 15.450 4 -

Final START LIST Pole Vault MEN Loppukilpailu OSANOTTAJALUETTELO Seiväshyppy MIEHET

10th IAAF World Championships in Athletics Helsinki From Saturday 6 August to Sunday 14 August 2005 Pole Vault MEN Seiväshyppy MIEHET ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHL Final START LIST Loppukilpailu OSANOTTAJALUETTELO ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETI 11 August 2005 18:35 START BIB COMPETITOR NAT YEAR Personal Best 2005 Best 1 885 Patrik KRISTIANSSON SWE 77 5.85 5.61 2 1044 Brad WALKER USA 81 5.90 5.90 3 31 Dmitri MARKOV AUS 75 6.05 5.75 4 398 Tim LOBINGER GER 72 6.00 5.82 5 469 Giuseppe GIBILISCO ITA 79 5.90 5.80 6 994 Nick HYSONG USA 71 5.90 5.70 7 808 Pavel GERASIMOV RUS 79 5.90 5.65 8 665 Rens BLOM NED 77 5.81 5.80 9 376 Danny ECKER GER 77 5.93 5.75 10 542 Daichi SAWANO JPN 80 5.83 5.83 11 820 Igor PAVLOV RUS 79 5.80 5.80 12 62 Kevin RANS BEL 82 5.60 5.60 SERIES 5.35 5.50 5.65 5.75 5.80 5.85 5.90 MARK COMPETITOR NAT AGE Record Date Record Venue WR6.14 Sergey BUBKA UKR 3031 Jul 1994 Sestriere CR6.05 Dmitri MARKOV AUS 269 Aug 2001 Edmonton WL6.00 Paul BURGESS AUS 2525 Feb 2005 Perth WORLD ALL-TIME / MAAILMAN KAIKKIEN AIKOJEN WORLD TOP 2005 / MAAILMAN 2005 MARK COMPETITOR COUNTRY DATE MARKCOMPETITOR COUNTRY DATE 6.14Sergey BUBKA UKR 31 Jul 94 6.00Paul BURGESS AUS 25 Feb 6.05Maksim -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

Sport and Physical Education in Germany

Sport and Physical Education in Germany Sport and physical education represent important components of German national life, from school and community participation, to elite, international level sport. This unique and comprehensive collection brings together material from leading German scholars to examine the role of sport and PE in Germany from a range of historical and contemporary perspectives. Key topics covered include: • Sport and PE in pre-war, post-war and re-unified Germany; • Sport and PE in schools; • Coach education; • Elite sport and sport science; • Women and sport; • Sport and recreation facilities. This book offers an illuminating insight into how sport and PE have helped to shape modern Germany. It is fascinating reading for anyone with an interest in the history and sociology of sport, and those working in German studies. Roland Naul is Professor of Sport Science and Sport Pedagogy, Essen University. He is ICSSPE Regional Director for Western Europe and Vice- President of ISCPES. Ken Hardman is a Reader in Education at the University of Manchester. He is a former president of ISCPES and a Fellow of the UK Physical Education Association. International Society for Comparative Physical Education and Sport Series Series Editor: Ken Hardman University of Manchester Other titles in the series include: Sport and Physical Education in China Edited by James Riordan and Robin Jones Sport and Physical Education in Germany Edited by Roland Naul and Ken Hardman International Society for Comparative Physical Education and Sport London and New York First published 2002 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2005.