Portrait of Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching the Least Reached CCBA

CENTRAL COAST BAPTIST ASSOCIATION Reaching the Least Reached What is an unreached people Where do UPGs live? What are the largest unreached and an unengaged people people groups in the Bay Area? group? It will be a surprise to some people that some large, very Nobody knows for certain yet A people group is unreached unreached people groups live in the which the largest UPGs are in the Bay when the number of evangelical United States, and even within the Area, but we do know which of them Christians is less than 2% of its geography of the Central Coast are the largest in the world. We also population (UPG). It is further called Baptist Association. They represent know some of them that are certainly unengaged (UUPG) when there is no various regions of the world such as here in large numbers, mostly in Santa church planting methodology China, India and the Middle East. Clara, Alameda, San Francisco, San consistent with evangelical faith and They are adherents of world religions Mateo and Contra Costa counties. practice under way. “A people group such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, There are more UPGs here than there is not engaged when it has been Sikhism and Jainism. can ever be paid missionaries to work merely adopted, is the object of among them. It will take ordinary focused prayer, or is part of an Christians who are willing to pray and advocacy strategy.” (IMB) work in extraordinary ways so that Today there are 6,430 unreached people from every nation, tribe, and people groups around the world. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Research Project Report on All India Birth Rate of Parsi – Zoroastrians

Research Project Report on All India Birth Rate of Parsi – Zoroastrians from 2001 till 15 th August, 2007 Sponsored by: National Commission for Minorities Government of India New Delhi Research Project Report on All India Birth Rate of Parsi – Zoroastrians th from 2001 till 15 August, 2007 Prepared by Dr. (Miss) Mehroo D. Bengalee Member (Parsi) National Commission for Minorities Government Of India, New Delhi Under Internship Project for Commission Intern : Miss Aakannsha Sharma (01.06.07 – 31.08.07) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Given the uniqueness of the demographic trend of the Parsi community there is a need to conduct scientific studies on various issues related to the community. In this context the present study of all India birth rate of Parsi Zoroastrian from 2001 till 15 th August, 2007 is very important. Several people have contributed in various capacities for the successful completion of this national level project. My sincere thanks and deepest gratitude to all of them, especially, 1. Mr. Minoo Shroff, Chairman, Bombay Parsi Panchayat. 2. Prof. Nadir A Modi, Advocate and Solicitor. 3. Dr. (Ms) Karuna Gupta, Prof and Head, Post Graduate Dept. of Education (M. Ed), Gurukrupa College of Education, Mumbai. 4. Mrs. Feroza K Panthaky Mistree, Zoroastrian Studies. 5. Prof. Sarah Mathew, Head, Department of Education, Sathaye College, Mumbai. 6. Parsi anjumans affiliated to the All India Federation. 7. Principals of schools of Mumbai. 8. Administrative Officer of Bombay Petit Parsi General Hospital. 9. All individual respondents who cared to return the Proformas duly filled in. 10. Friends, who helped to compile the report. Within the constrain of the time-frame of three months, it was difficult to reach out to all Parsis scattered in every nook and corner of the country. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Annual Report 2017-18 31 Oct 2018.Cdr

Annual Report 2017-18 Werner kulhbrandt Werner Kulhbrandt Richard Henderson Nobel Laureates visited TDU The University of Trans-Disciplinary Health Sciences and Technology One of the 110 Medicinal Plant Conservation Area (MPCA) National Herbarium of Medicinal Botanicals Ayurveda Biology Laboratory Workshop on Functional Genomics for Professionals International Folk Healers Conference Community Participation in Sustainable Harvesting of Med. Plants Mr. Ratan Tata visit to FRLHT 100 Bed Integrative Healthcare Center Annual Report 2017-2018 2.3. Board of Governors of TDU Sam Pitroda Chairman Chancellor, TDU 301,Trinity Lane, OakBrook, Illinois, 60523, USA Ph: +630-928-0890 Prof. S Ramaswamy Co-Chairman Dean InStem, NCBS, Bangalore #35, HMT Layout, RT Nagar Main Road, BHD BMTC Bus Depot. Bangalore - 560032 Prof. Darshan Shankar Member Vice Chancellor, TDU No. 96-3, Jakkur Sneha Layout, Jakkur, Bangalore - 560 064 Commander Giridharan R. Ex-officio Member Registrar, TDU B-302, Shravanthi Paradise 70, Jaraganahalli, Kanakapura Main road, J P Nagar, 6th Phase, Bangalore - 560078 Prof. Pankaj Chandra Member Vice Chancellor, Ahmedabad University. Commerce Six Roads, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad - 380009, Gujarat, India. S.V. Ranganath Member Former Chief Secretary, Govt. of Karnataka No. 25, 8th Cross, 2nd Block, Jayanagar, Bangalore - 560011 Manoj Kumar Special Invitee Nominee of Tata Trusts Villa 180 Lane 8, Adarsh Palm Retreat Devarabeesanahalli, Outer Ring Road, Bangalore - 560103 Prof. Jyotsna Dhawan Member Chief Scientist Room no. E106, Centre for Cellular & Molecular Biology, Habsiguda, Uppal Road, Hyderabad - 500007 Prof. Hosahalli Subramanya, Member Director IBAB & Biocon Chair. IBAB, BiotechPark, Electronics City Phase I, Bangalore - 560 100, A.V. Balasubramanian Member Director, Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems (CIKS), Chennai B-3, Rajalakshmi Complex, 2nd Floor, No. -

Growth of Parsi Population India: Demographic Perspectives

Unisa et al Demographic Predicament of Parsis in India Sayeed Unisa, R.B.Bhagat, and T.K.Roy International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India Email: [email protected] www.iipsindia.org Paper presented at XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference 27 September to 2 October 2009 Marrakech 1 Unisa et al Demographic Predicament of Parsis in India Sayeed Unisa, R.B.Bhagat, and T.K.Roy International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai E-mail: [email protected] The Parsi community in India is perhaps the only community outside Europe to have experienced dramatic population and fertility decline. This indicates that a country that is experiencing high population growth can also have communities that have different kinds of demographic patterns. Parsis are a small but prosperous religious community that maintained some sort of social isolation by practising endogamy and not accepting any new converts to their faith. Their population started declining since 1941 and the explanations that are put forth pertain to the issues of under- enumeration, fertility decline and emigration. In this paper, the relative importance of these factors in the light of 2001 Census is examined. This study demonstrates that the unprecedented fall in fertility among Parsis is the prime contributor to its declining population size. Also in this paper, the population of Parsis is projected up to the year 2051. 2 Unisa et al INTRODUCTION Parsis are perhaps the only community which had experienced dramatic population and fertility decline outside Europe (Coale, 1973; Coale and Watkin, 1986). This indicates that in a country that is experiencing high population growth can also have communities, which amazingly have different kinds of demographic pattern (Axelrod, 1990; Lorimer, 1954). -

Middle Eastern Women on the Move Middle Eastern Women on the Move

Middle East Project MIDDLE EASTERN WOMEN ON THE MOVE MIDDLE EASTERN WOMEN ON THE MOVE Middle East Project MIDDLE EASTERN WOMEN ON THE MOVE Openings for and the Constraints on Women’s Political Participation in the Middle East ©2003 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. www.wilsoncenter.org WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS LEE H. HAMILTON, DIRECTOR BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joseph B. Gildenhorn, Chair; David A. Metzner, Vice Chair. Public Members: James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress; John W. Carlin, Archivist of the United States; Bruce Cole, Chair, National Endowment for the Humanities; Roderick R. Paige, Secretary, U.S. Department of Education; Colin L. Powell, Secretary, U.S. Department of State; Lawrence M. Small, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution; Tommy G. Thompson, Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Private Citizen Members: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., Carol Cartwright, Donald E. Garcia, Bruce S. Gelb, Daniel L. Lamaute, Tamala L. Longaberger, Thomas R. Reedy WILSON COUNCIL Bruce S. Gelb, President. Diane Aboulafia-D'Jaen, Elias F. Aburdene, Charles S. Ackerman, B.B. Andersen, Cyrus A. Ansary, Lawrence E. Bathgate II, John Beinecke, Joseph C. Bell, Steven Alan Bennett, Rudy Boschwitz, A. Oakley Brooks, Melva Bucksbaum, Charles W. Burson, Conrad Cafritz, Nicola L. Caiola, Raoul L. Carroll, Scott Carter, Albert V. Casey, Mark Chandler, Peter B. Clark, Melvin Cohen, William T. Coleman, Jr., Michael D. DiGiacomo, Sheldon Drobny, F. Samuel Eberts III, J. David Eller, Mark Epstein, Melvyn J. Estrin, Sim Farar, Susan Farber, Joseph H. Flom, John H. Foster, Charles Fox, Barbara Hackman Franklin, Norman Freidkin, Morton Funger, Gregory M. -

48P. Rs.14 a Biography of Abraham Lincoln, the President of America

01. ABRAHAM LINCON Rajeshwari krishna Bangalore: Sapna Book House 2000; 48p. Rs.14 A biography of Abraham Lincoln, the president of America. 02. YERUVA BA KEDARA SHIKHARA Rao, Lelavathi. S. Surathkal: Bharathi prakashana 2000; 30p. Rs.18 A travelogue for children. The experience of the travel is given interestingly in the book. 03. AJJI HELIDA KATHEGALU Shetti, Parathamma Mahalinga Bangalore: Nava Karnataka Prakashana 1998; 56p. Rs.12 A collection of short stories written for children. The stories came from grandmaa's tales. 04. AKASHA VEEKSH ANEGE MARGADARSHI Shankar, P.S. Bangalore: Karnataka Rajya Vijnana Parishat 1988; 38p. Rs.4 A book on seeing sky and understanding the stars in scientific way. 05. AKBAR MATTU B EE RBAL L Mehra, Komal Bangalore: Sapna Book House 32p. Rs.25 A book on the inteligency of Beerball. The book contains many short stories of humour. 06. AKKASALIYA AASE Hoysala, A.L. Mysore: Kavyalaya 1991; Rs.5 A story of the goldsmith and carpentar . The story tells about the simplicity of the carpenter. 07. ALAKAGE AJJIYA PATRAGALU Bhat , K. Poornima Bangalore: Nava Karnataka Prakashana 1999; 40p. Rs.12 A book contains letters to Alaka , a small girl by her grand mother. She advises to develop a good habits. 08. AMBALIPURADA KUMBARA Mysore: Kavyalaya 1992; 32p. Rs.6 A book of short stories based on folklore. The book contains two interesting stories for children. 09 . AMOOLYA RATNA Ramaswamy, Kamala Bangalore: Nava Karnataka Prakashana 1992; Rs.7 Stories of yester years for children. The book contains twelve short stories with interesting pictures. 10. ARANYAGRAMAKKE PRAVASA Neelambari Bangalore: Nava Karnataka Prakashana 1991; Rs.7 A collection of short stories for children's. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

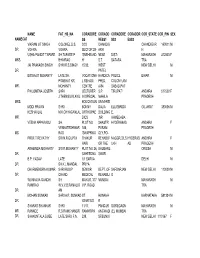

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century Thesis submitted for the dc^ee fif DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By AJAZ BANG Under the supervision of PROF. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarb- 1983 T388S 3 0 JAH 1392 ?'0A/ CHE':l!r,D-2002 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE SS46 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis entitled 'Soci•-Political Condition Ml VB Wtmmimt of Gujarat / during the fifteenth Century' is an original research work carried out by Aijaz Bano under my Supervision, I permit its submission for the award of the Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy.. /-'/'-ji^'-^- (Proi . Jrqiaao;r: Al«fAXamn Khan) tc ?;- . '^^•^\ Contents Chapters Page No. I Introduction 1-13 II The Population of Gujarat Dxiring the Sixteenth Century 14 - 22 III Gujarat's External Trade 1407-1572 23 - 46 IV The Trading Cotnmxinities and their Role in the Sultanate of Gujarat 47 - 75 V The Zamindars in the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1407-1572 76 - 91 VI Composition of the Nobility Under the Sultans of Gujarat 92 - 111 VII Institutional Featvires of the Gujarati Nobility 112 - 134 VIII Conclusion 135 - 140 IX Appendix 141 - 225 X Bibliography 226 - 238 The abljreviations used in the foot notes are f ollov.'ing;- Ain Ain-i-Akbarl JiFiG Arabic History of Gujarat ARIE Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy SIAPS Epiqraphia Indica •r'g-acic and Persian Supplement EIM Epigraphia Indo i^oslemica FS Futuh-^ffi^Salatin lESHR The Indian Economy and Social History Review JRAS Journal of Asiatic Society ot Bengal MA Mi'rat-i-Ahmadi MS Mirat~i-Sikandari hlRG Merchants and Rulers in Giijarat MF Microfilm. -

SECRETARIAT LIBRARY, VIDHANA SOUDHA Govt

SECRETARIAT LIBRARY, VIDHANA SOUDHA Govt. Of Karnataka ROOM NO. 11, GROUND FLOOR, VIDHANA SOUDHA, BANGALORE-560001. January 17, 2014 Current Awareness List for Books Group By: Subject S.N. Title Details 1 S.N. 1 Accession No 128644 Accession Date: 09/11/2012 Title Details Developments in Science and Technology. / Kalpana Rajaram ; Suri, R.K. New Delhi: Spectrum Publications; 2012, ISBN: 81-7930-452-3 S.N. 2 Accession No 128722 Accession Date: 21/12/2012 Title Details Spot The Next Economic Bubble. / Thirani, Saurabh New Delhi: Network 18 Publications Private Limited; 2012, ISBN: 978-93-80200-58-3 S.N. 3 Accession No 128868 Accession Date: 16/02/2013 Title Details Shri Rama Janmabhoomi Teerpu. / Narayanacharya, K.S. Hubli: Sahitya Prakashana; 2012, ISBN: 2012 S.N. 4 Accession No 128869 Accession Date: 16/02/2013 Call No 347.077 NAR Title Details Shri Rama Janmabhoomi Teerpu. / Narayanacharya, K.S. Hubli: Sahitya Prakashana; 2012, ISBN: 2012 S.N. 5 Accession No 128878 Accession Date: 16/02/2013 Call No 928.94814 USH Title Details Vaidehi : A Monograph on the Life and Works of Kendra Sahitya Akademi Awardee Kannada Literateur. / Usha, S. Bangalore: Navakarnataka Publications Pvt Ltd; 2012, ISBN: 978-81-8467-317-3 S.N. 6 Accession No 128879 Accession Date: 16/02/2013 Call No 928.94814 USH Title Details Vaidehi : A Monograph on the Life and Works of Kendra Sahitya Akademi Awardee Kannada Literateur. / Usha, S. Bangalore: Navakarnataka Publications Pvt Ltd; 2012, ISBN: 978-81-8467-317-3 S.N. 7 Accession No 128884 Accession Date: 16/02/2013 Call No 954.052 VAR Title Details Chanakyas New Manifesto. -

![Bangalore (Or ???????? Bengaluru, ['Be?G??U??U] ( Listen)) Is the Capital City O F the Indian State of Karnataka](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7497/bangalore-or-bengaluru-be-g-u-u-listen-is-the-capital-city-o-f-the-indian-state-of-karnataka-1767497.webp)

Bangalore (Or ???????? Bengaluru, ['Be?G??U??U] ( Listen)) Is the Capital City O F the Indian State of Karnataka

Bangalore (or ???????? Bengaluru, ['be?g??u??u] ( listen)) is the capital city o f the Indian state of Karnataka. Located on the Deccan Plateau in the south-east ern part of Karnataka. Bangalore is India's third most populous city and fifth-m ost populous urban agglomeration. Bangalore is known as the Silicon Valley of In dia because of its position as nation's leading Information technology (IT) expo rter.[7][8][9] Located at a height of over 3,000 feet (914.4 m) above sea level, Bangalore is known for its pleasant climate throughout the year.[10] The city i s amongst the top ten preferred entrepreneurial locations in the world.[11] A succession of South Indian dynasties, the Western Gangas, the Cholas, and the Hoysalas ruled the present region of Bangalore until in 1537 CE, Kempé Gowda a feu datory ruler under the Vijayanagara Empire established a mud fort considered to be the foundation of modern Bangalore. Following transitory occupation by the Ma rathas and Mughals, the city remained under the Mysore Kingdom. It later passed into the hands of Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan, and was captured by the Bri tish after victory in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1799), who returned administr ative control of the city to the Maharaja of Mysore. The old city developed in t he dominions of the Maharaja of Mysore, and was made capital of the Princely Sta te of Mysore, which existed as a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj. In 1809, the British shifted their cantonment to Bangalore, outside the old city , and a town grew up around it, which was governed as part of British India.