Middle Eastern Women on the Move Middle Eastern Women on the Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching the Least Reached CCBA

CENTRAL COAST BAPTIST ASSOCIATION Reaching the Least Reached What is an unreached people Where do UPGs live? What are the largest unreached and an unengaged people people groups in the Bay Area? group? It will be a surprise to some people that some large, very Nobody knows for certain yet A people group is unreached unreached people groups live in the which the largest UPGs are in the Bay when the number of evangelical United States, and even within the Area, but we do know which of them Christians is less than 2% of its geography of the Central Coast are the largest in the world. We also population (UPG). It is further called Baptist Association. They represent know some of them that are certainly unengaged (UUPG) when there is no various regions of the world such as here in large numbers, mostly in Santa church planting methodology China, India and the Middle East. Clara, Alameda, San Francisco, San consistent with evangelical faith and They are adherents of world religions Mateo and Contra Costa counties. practice under way. “A people group such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, There are more UPGs here than there is not engaged when it has been Sikhism and Jainism. can ever be paid missionaries to work merely adopted, is the object of among them. It will take ordinary focused prayer, or is part of an Christians who are willing to pray and advocacy strategy.” (IMB) work in extraordinary ways so that Today there are 6,430 unreached people from every nation, tribe, and people groups around the world. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

The Capitol Dome

THE CAPITOL DOME The Capitol in the Movies John Quincy Adams and Speakers of the House Irish Artists in the Capitol Complex Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETYVOLUME 55, NUMBER 22018 From the Editor’s Desk Like the lantern shining within the Tholos Dr. Paula Murphy, like Peart, studies atop the Dome whenever either or both America from the British Isles. Her research chambers of Congress are in session, this into Irish and Irish-American contributions issue of The Capitol Dome sheds light in all to the Capitol complex confirms an import- directions. Two of the four articles deal pri- ant artistic legacy while revealing some sur- marily with art, one focuses on politics, and prising contributions from important but one is a fascinating exposé of how the two unsung artists. Her research on this side of can overlap. “the Pond” was supported by a USCHS In the first article, Michael Canning Capitol Fellowship. reveals how the Capitol, far from being only Another Capitol Fellow alumnus, John a palette for other artist’s creations, has been Busch, makes an ingenious case-study of an artist (actor) in its own right. Whether as the historical impact of steam navigation. a walk-on in a cameo role (as in Quiz Show), Throughout the nineteenth century, steam- or a featured performer sharing the marquee boats shared top billing with locomotives as (as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), the the most celebrated and recognizable motif of Capitol, Library of Congress, and other sites technological progress. -

Towards a Human Security Approach to Peacebuilding 1

www.isp.unu.edu Number 2, 2010 Overview In recent decades, international Towards a Human Security peacebuilding and reconstruction after civil wars have managed to promote stability and contain conflict in many Approach to Peacebuilding regions around the world, ending violence and enabling communities to rebuild their lives and societies. HAT IS THE RECORD, EFFECTIVENESS AND LEGACY However, the peacebuilding record of liberal approaches to peacebuilding in conflict-prone and post-conflict indicates that there are problems W societies? Aside from promoting stability and containing conflict, why does related to the effectiveness and international peacebuilding have a mixed—or even poor—record in promoting legitimacy of peacebuilding, especially welfare, equitable human development and inclusive democratic politics? Have these related to the promotion of liberal shortcomings jeopardized overall peacebuilding objectives and contributed to democracy, market reform and state questions about its legitimacy? How might alternative approaches to peacebuilding, institutions. This brief considers these based upon welfare and public service delivery, promote a more sustainable and limitations and argues that a new human security-based approach may inclusive form of peace? These questions allude to a core concern regarding offer insights for a more sustainable international peacebuilding: the limitations of existing approaches and the need form of peacebuilding. for greater emphasis upon welfare economics, human development and local engagement. Peacebuilding -

Research Project Report on All India Birth Rate of Parsi – Zoroastrians

Research Project Report on All India Birth Rate of Parsi – Zoroastrians from 2001 till 15 th August, 2007 Sponsored by: National Commission for Minorities Government of India New Delhi Research Project Report on All India Birth Rate of Parsi – Zoroastrians th from 2001 till 15 August, 2007 Prepared by Dr. (Miss) Mehroo D. Bengalee Member (Parsi) National Commission for Minorities Government Of India, New Delhi Under Internship Project for Commission Intern : Miss Aakannsha Sharma (01.06.07 – 31.08.07) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Given the uniqueness of the demographic trend of the Parsi community there is a need to conduct scientific studies on various issues related to the community. In this context the present study of all India birth rate of Parsi Zoroastrian from 2001 till 15 th August, 2007 is very important. Several people have contributed in various capacities for the successful completion of this national level project. My sincere thanks and deepest gratitude to all of them, especially, 1. Mr. Minoo Shroff, Chairman, Bombay Parsi Panchayat. 2. Prof. Nadir A Modi, Advocate and Solicitor. 3. Dr. (Ms) Karuna Gupta, Prof and Head, Post Graduate Dept. of Education (M. Ed), Gurukrupa College of Education, Mumbai. 4. Mrs. Feroza K Panthaky Mistree, Zoroastrian Studies. 5. Prof. Sarah Mathew, Head, Department of Education, Sathaye College, Mumbai. 6. Parsi anjumans affiliated to the All India Federation. 7. Principals of schools of Mumbai. 8. Administrative Officer of Bombay Petit Parsi General Hospital. 9. All individual respondents who cared to return the Proformas duly filled in. 10. Friends, who helped to compile the report. Within the constrain of the time-frame of three months, it was difficult to reach out to all Parsis scattered in every nook and corner of the country. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

For Immediate Release

‘LIVING OUT LOUD’ PRODUCTION BIOS JACK GROSSBART (Executive Producer) – Jack Grossbart is an independent producer who has produced nearly 40 telefilms in the last 20 years. Partnered with Linda Kent in Grossbart Kent Productions, their recent TV movie “Why I wore Lipstick to my Mastectomy,” starring Sarah Chalke, earned them the 2007 Gracie Award, a 2007 Humanitas Prize nomination, and a 2007 Emmy nomination for Outstanding Made for Television Movie. Before forming Grossbart Kent Productions, Grossbart was partnered with Joan Barnett in Grossbart/Barnett Productions for 15 years, producing telefilms for CBS, NBC, ABC and HBO, as well as some of the newly emerging cable channels. Among their productions have been “Any Mother’s Son,” “The Marriage Fool,” starring Walter Matthau and Carol Burnett, “Unforgivable,” starring John Ritter, the award winning “Something to Live For: The Alison Gertz Story,” “Leave of Absence” starring Brian Dennehy and Jacqueline Bisset, “Last Wish” starring Patty Duke and Maureen Stapleton, and HBO’s “The Comrades of Summer,” starring Joe Mantegna. Grossbart executive produced the Emmy nominated miniseries “Echoes in the Darkness,” based on the best selling Joseph Wambaugh book, The Preppie Murder. In the half-hour series arena, Grossbart executive produced the Valerie Bertinelli series “Sydney” for CBS and “Café Americain” for NBC. Grossbart graduated from Rutgers University with a B.A. in English and Dramatic Arts and started working in the mailroom at ICM, where he worked his way up to become an agent in their theater department. After four years, he moved to Los Angeles to work for the William Morris Agency where he was an agent in the television department for five years. -

Growth of Parsi Population India: Demographic Perspectives

Unisa et al Demographic Predicament of Parsis in India Sayeed Unisa, R.B.Bhagat, and T.K.Roy International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India Email: [email protected] www.iipsindia.org Paper presented at XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference 27 September to 2 October 2009 Marrakech 1 Unisa et al Demographic Predicament of Parsis in India Sayeed Unisa, R.B.Bhagat, and T.K.Roy International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai E-mail: [email protected] The Parsi community in India is perhaps the only community outside Europe to have experienced dramatic population and fertility decline. This indicates that a country that is experiencing high population growth can also have communities that have different kinds of demographic patterns. Parsis are a small but prosperous religious community that maintained some sort of social isolation by practising endogamy and not accepting any new converts to their faith. Their population started declining since 1941 and the explanations that are put forth pertain to the issues of under- enumeration, fertility decline and emigration. In this paper, the relative importance of these factors in the light of 2001 Census is examined. This study demonstrates that the unprecedented fall in fertility among Parsis is the prime contributor to its declining population size. Also in this paper, the population of Parsis is projected up to the year 2051. 2 Unisa et al INTRODUCTION Parsis are perhaps the only community which had experienced dramatic population and fertility decline outside Europe (Coale, 1973; Coale and Watkin, 1986). This indicates that in a country that is experiencing high population growth can also have communities, which amazingly have different kinds of demographic pattern (Axelrod, 1990; Lorimer, 1954). -

Jewish Experience on Film an American Overview

Jewish Experience on Film An American Overview by JOEL ROSENBERG ± OR ONE FAMILIAR WITH THE long history of Jewish sacred texts, it is fair to characterize film as the quintessential profane text. Being tied as it is to the life of industrial science and production, it is the first truly posttraditional art medium — a creature of gears and bolts, of lenses and transparencies, of drives and brakes and projected light, a creature whose life substance is spreadshot onto a vast ocean of screen to display another kind of life entirely: the images of human beings; stories; purported history; myth; philosophy; social conflict; politics; love; war; belief. Movies seem to take place in a domain between matter and spirit, but are, in a sense, dependent on both. Like the Golem — the artificial anthropoid of Jewish folklore, a creature always yearning to rise or reach out beyond its own materiality — film is a machine truly made in the human image: a late-born child of human culture that manifests an inherently stubborn and rebellious nature. It is a being that has suffered, as it were, all the neuroses of its mostly 20th-century rise and flourishing and has shared in all the century's treach- eries. It is in this context above all that we must consider the problematic subject of Jewish experience on film. In academic research, the field of film studies has now blossomed into a richly elaborate body of criticism and theory, although its reigning schools of thought — at present, heavily influenced by Marxism, Lacanian psycho- analysis, and various flavors of deconstruction — have often preferred the fashionable habit of reasoning by decree in place of genuine observation and analysis. -

Human Security Twenty Years On

Expert Analysis June 2014 Human security twenty years on By Shahrbanou Tadjbakhsh Executive summary The concept of human security, which made its international debut in the 1994 UNDP Human Development Report, adds a people-centred dimension to the traditional security, development and human rights frameworks while locating itself in the area where they converge. Ever since, a number of countries have used the concept for their foreign and aid policies. Although it became the subject of a 2012 General Assembly Resolution, the concept still courts controversy and rejection twenty years after its introduction. Politically, its close association with the notion of the Responsibility to Protect in debates about international interventions has alienated Southern countries that are sceptical about violations of state sovereignty and new conditionali- ties for receiving aid. No country has adopted it as a goal at the national level, raising scepticism about its utility for domestic policymaking. Yet the concept represents a malleable tool for ana- lysing the root causes of threats and their multidimensional consequences for different types of insecurities. It can be operationalised through applying specific principles to policymaking and can be used as an evaluative tool for gauging the impact of interventions on the dynamics of other fields. The article suggests that Norway not only pursues the goal of human security at the global level, but that it also leads in adopting it as a national goal by scrutinising the country’s domestic policies using this approach. Still shaky after twenty years1 – have negated its value as an analytical framework, Often, in the space where the policy, political and academic rejected its utility as a policy agenda, and even opposed its arenas converge, much ink is spilled in defence of a very very existence as a concept. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

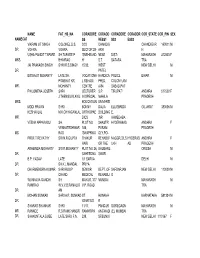

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century Thesis submitted for the dc^ee fif DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By AJAZ BANG Under the supervision of PROF. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarb- 1983 T388S 3 0 JAH 1392 ?'0A/ CHE':l!r,D-2002 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE SS46 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis entitled 'Soci•-Political Condition Ml VB Wtmmimt of Gujarat / during the fifteenth Century' is an original research work carried out by Aijaz Bano under my Supervision, I permit its submission for the award of the Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy.. /-'/'-ji^'-^- (Proi . Jrqiaao;r: Al«fAXamn Khan) tc ?;- . '^^•^\ Contents Chapters Page No. I Introduction 1-13 II The Population of Gujarat Dxiring the Sixteenth Century 14 - 22 III Gujarat's External Trade 1407-1572 23 - 46 IV The Trading Cotnmxinities and their Role in the Sultanate of Gujarat 47 - 75 V The Zamindars in the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1407-1572 76 - 91 VI Composition of the Nobility Under the Sultans of Gujarat 92 - 111 VII Institutional Featvires of the Gujarati Nobility 112 - 134 VIII Conclusion 135 - 140 IX Appendix 141 - 225 X Bibliography 226 - 238 The abljreviations used in the foot notes are f ollov.'ing;- Ain Ain-i-Akbarl JiFiG Arabic History of Gujarat ARIE Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy SIAPS Epiqraphia Indica •r'g-acic and Persian Supplement EIM Epigraphia Indo i^oslemica FS Futuh-^ffi^Salatin lESHR The Indian Economy and Social History Review JRAS Journal of Asiatic Society ot Bengal MA Mi'rat-i-Ahmadi MS Mirat~i-Sikandari hlRG Merchants and Rulers in Giijarat MF Microfilm.