Sunil Manghani - Picturing Berlin: Piecing Together a Public Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson A Thesis submitted by: Andre Weiss B. A. 1998 Supervisor: Dr. Gavin Stamp Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Architecture Mackintosh School of Architecture, The University of Glasgow September 1999 ProQuest N um ber: 13833922 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13833922 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................9 1. The Previous Claims of an InfluentialRelationship ............................................18 2. An Exploration of the Individual Backgrounds of Thomson and Schinkel .............................................................................................................38 -

Class, Nation and the Folk in the Works of Gustav Freytag (1816-1895)

Private Lives and Collective Destinies: Class, Nation and the Folk in the Works of Gustav Freytag (1816-1895) Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benedict Keble Schofield Department of Germanic Studies University of Sheffield June 2009 Contents Abstract v Acknowledgements vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Literature and Tendenz in the mid-19th Century 1 1.2 Gustav Freytag: a Literary-Political Life 2 1.2.1 Freytag's Life and Works 2 1.2.2 Critical Responses to Freytag 4 1.3 Conceptual Frameworks and Core Terminology 10 1.4 Editions and Sources 1 1 1.4.1 The Gesammelte Werke 1 1 1.4.2 The Erinnerungen aus meinem Leben 12 1.4.3 Letters, Manuscripts and Archival Material 13 1.5 Structure of the Thesis 14 2 Political and Aesthetic Trends in Gustav Freytag's Vormiirz Poetry 17 2.1 Introduction: the Path to Poetry 17 2.2 In Breslau (1845) 18 2.2.1 In Breslau: Context, Composition and Theme 18 2.2.2 Politically Responsive Poetry 24 2.2.3 Domestic and Narrative Poetry 34 2.2.4 Poetic Imagination and Political Engagement 40 2.3 Conclusion: Early Concerns and Future Patterns 44 3 Gustav Freytag's Theatrical Practice in the 1840s: the Vormiirz Dramas 46 3.1 Introduction: from Poetry to Drama 46 3.2 Die Brautfahrt, oder Kunz von der Rosen (1841) 48 3.2.1 Die Brautfahrt: Context, Composition and Theme 48 3.2.2 The Hoftheater Competition of 1841: Die Brautfahrt as Comedy 50 3.2.3 Manipulating the Past: the Historical Background to Die Brautfahrt 53 3.2.4 The Question of Dramatic Hero: the Function ofKunz 57 3.2.5 Sub-Conclusion: Die -

THE DAILY DIARY of PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER DATE ~Mo

THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER DATE ~Mo.. Day, k’r.) U.S. EMBASSY RESIDENCE JULY 15, 1978 BONN, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY THE DAY 6:00 a.m. SATURDAY WOKE From 1 To R The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. The President had breakfast with Secretary of State Cyrus R. Vance. 7: 48 The President and the First Lady went to their motorcade. 7:48 8~4 The President and the First Lady motored from the U.S. Embassy residence to the Cologne/Bonn Airport. 828 8s The President and the First Lady flew by Air Force One from the Cologne/Bonn Airport to Rhein-Main Air Base, Frankfurt, Germany. For a list of passengers, see 3PENDIX "A." 8:32 8: 37 The President talked with Representative of the U.S. to the United Nations Andrew J. Young. Air Force One arrived at Rhein-Main Air Base. The President and the First Lady were greeted by: Helmut Schmidt, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) Mrs. Helmut Schmidt Holger Borner, Minister-President, Hesse Mrs. Holger Borner Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Minister of Foreign Affairs, FRG Hans Apel, Minister of Defense, FRG Wolfgang J, Lehmann, Consul General, FRG Mrs. Wolfgang J. Lehmann Gen. William J. Evans, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Air Force, Europe Col. Robert D. Springer, Wing Commander, Rhein-Main Air Base Gen. Gethard Limberg, Chief of the German Air Force 8:45 g:oo The President and Chancellor Schmidt participated in a tour of static display of U.S. -

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR: From Rejection to Selective Commemoration Corinna Munn Department of History Columbia University April 9, 2014 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Volker Berghahn, for his support and guidance in this project. I also thank my second reader, Hana Worthen, for her careful reading and constructive advice. This paper has also benefited from the work I did under Wolfgang Neugebauer at the Humboldt University of Berlin in the summer semester of 2013, and from the advice of Bärbel Holtz, also of Humboldt University. Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 2. Chronology and Context………………………………………………………….4 3. The Geschichtsbild in the GDR…………………………………………………..8 3.1 What is a Geschichtsbild?..............................................................................8 3.2 The Function of the Geschichtsbild in the GDR……………………………9 4. Prussia’s Changing Role in the Geschichtsbild of the GDR…………………….11 4.1 1945-1951: The Post-War Period………………………………………….11 4.1.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………11 4.1.2 Public Symbols and Events: The fate of the Berliner Stadtschloss…14 4.1.3 Film: Die blauen Schwerter………………………………………...19 4.2 1951-1973: Building a Socialist Society…………………………………...22 4.2.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………22 4.2.2 Public Symbols and Events: The Neue Wache and the demolition of Potsdam’s Garnisonkirche…………………………………………..30 4.2.3 Film: Die gestohlene Schlacht………………………………………34 4.3 1973-1989: The Rediscovery of Prussia…………………………………...39 4.3.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………39 4.3.2 Public Symbols and Events: The restoration of the Lindenforum and the exhibit at Sans Souci……………………………………………42 4.3.3 Film: Sachsens Glanz und Preußens Gloria………………………..45 5. -

Neue Wache (1818-1993) Since 1993 in the Federal Republic of Germany the Berlin Neue Wache Has Served As a Central Memorial Comm

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI 2011, No 1 ZbIGNIEw MAZuR Poznań NEUE WACHE (1818-1993) Since 1993 in the Federal Republic of Germany the berlin Neue wache has served as a central memorial commemorating the victims of war and tyranny, that is to say it represents in a synthetic gist the binding German canon of collective memo- ry in the most sensitive area concerning the infamous history of the Third Reich. The interior decor of Neue wache, the sculpture placed inside and the commemorative plaques speak a lot about the official historical policy of the German government. Also the symbolism of the place itself is of significance, and a plaque positioned to the left of the entrance contains information about its history. Indeed, the history of Neue wache was extraordinary, starting as a utility building, though equipped with readable symbolic features, and ending up as a place for a national memorial which has been redesigned three times. Consequently, the process itself created a symbolic palimpsest with some layers completely obliterated and others remaining visible to the eye, and with new layers added which still retain a scent of freshness. The first layer is very strongly connected with the victorious war of “liberation” against Na- poleonic France, which played the role of a myth that laid the foundations for the great power of Prussia and then of the later German Empire. The second layer was a reflection of the glorifying worship of the fallen soldiers which developed after world war I in European countries and also in Germany. The third one was an ex- pression of the historical policy of the communist-run German Democratic Republic which emphasized the victims of class struggle with “militarism” and “fascism”. -

He Big “Mitte-Struggle” Politics and Aesthetics of Berlin's Post

Martin Gegner he big “mitt e-struggl e” politics and a esth etics of t b rlin’s post-r nification e eu urbanism proj ects Abstract There is hardly a metropolis found in Europe or elsewhere where the 104 urban structure and architectural face changed as often, or dramatically, as in 20 th century Berlin. During this century, the city served as the state capital for five different political systems, suffered partial destruction pós- during World War II, and experienced physical separation by the Berlin wall for 28 years. Shortly after the reunification of Germany in 1989, Berlin was designated the capital of the unified country. This triggered massive building activity for federal ministries and other governmental facilities, the majority of which was carried out in the old city center (Mitte) . It was here that previous regimes of various ideologies had built their major architectural state representations; from to the authoritarian Empire (1871-1918) to authoritarian socialism in the German Democratic Republic (1949-89). All of these époques still have remains concentrated in the Mitte district, but it is not only with governmental buildings that Berlin and its Mitte transformed drastically in the last 20 years; there were also cultural, commercial, and industrial projects and, of course, apartment buildings which were designed and completed. With all of these reasons for construction, the question arose of what to do with the old buildings and how to build the new. From 1991 onwards, the Berlin urbanism authority worked out guidelines which set aesthetic guidelines for all construction activity. The 1999 Planwerk Innenstadt (City Center Master Plan) itself was based on a Leitbild (overall concept) from the 1980s called “Critical Reconstruction of a European City.” Many critics, architects, and theorists called it a prohibitive construction doctrine that, to a certain extent, represented conservative or even reactionary political tendencies in unified Germany. -

Things to Do in Berlin – a List of Options 19Th of June (Wednesday

Things to do in Berlin – A List of Options Dear all, in preparation for the International Staff Week, we have composed an extensive list of activities or excursions you could participate in during your stay in Berlin. We hope we have managed to include something for the likes of everyone, however if you are not particularly interested in any of the things listed there are tons of other options out there. We recommend having a look at the following websites for further suggestions: https://www.berlin.de/en/ https://www.top10berlin.de/en We hope you will have a wonderful stay in Berlin. Kind regards, ??? 19th of June (Wednesday) / Things you can always do: - Famous sights: Brandenburger Tor, Fernsehturm (Alexanderplatz), Schloss Charlottenburg, Reichstag, Potsdamer Platz, Schloss Sanssouci in Potsdam, East Side Gallery, Holocaust Memorial, Pfaueninsel, Topographie des Terrors - Free Berlin Tours: https://www.neweuropetours.eu/sandemans- tours/berlin/free-tour-of-berlin/ - City Tours via bus: https://city- sightseeing.com/en/3/berlin/45/hop-on-hop-off- berlin?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI_s2es 9Pe4AIVgc13Ch1BxwBCEAAYASAAEgInWvD_BwE - City Tours via bike: https://www.fahrradtouren-berlin.com/en/ - Espresso-Concerts: https://www.konzerthaus.de/en/espresso- concerts - Selection of famous Museums (Museumspass Berlin buys admission to the permanent exhibits of about 50 museums for three consecutive days. It costs €24 (concession €12) and is sold at tourist offices and participating museums.): Pergamonmuseum, Neues Museum, -

Architecture in Berlin. a Walk Through History Instructor

Course title: Architecture in Berlin. A Walk through History Instructor: Dr. Gernot Weckherlin Email address: [email protected] Track: A-Track Language of instruction: English Contact hours: 48 (6 per day) ECTS-Credits: 5 Prerequisites: Students should be able to speak and read English at the upper intermediate level (B2) or higher. Course description This course gives a wide overview of the development of public and private architecture in Berlin during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. Following an introduction to the urban development and architectural history of the Modern era, the Neo-Classical period will be surveyed with special reference to the works of Schinkel. This will be followed by classes on architecture of the German Reich after 1871, which was characterized by both modern and conservative tendencies and the manifold activities during the time of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s such as the Housing Revolution. The architecture of the Nazi period will be examined, followed by the developments in East and West Berlin after the Second World War. The course concludes with a detailed review of the city’s more recent and current architectural profiles, including an analysis of the conflicts concerning the re-design of Berlin after the Cold War and the German reunification. Seven walking tours to historically significant buildings and sites are included (Unter den Linden, Gendarmenmarkt, New Housing Estates, Chancellory, Potsdamer Platz, Holocaust Memorial etc.). The course aims to offer a deeper understanding of the interdependence of Berlin’s architecture and the city’s social and political structures. It considers Berlin as a model for the highways and by-ways of a European capital in modern times. -

Germany Berlin Tiergarten Tunnel Verkehrsanlagen Im Zentralen

Germany Berlin Tiergarten Tunnel Verkehrsanlagen im zentralen Bereich – VZB This report was compiled by the German OMEGA Team, Free University Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Please Note: This Project Profile has been prepared as part of the ongoing OMEGA Centre of Excellence work on Mega Urban Transport Projects. The information presented in the Profile is essentially a 'work in progress' and will be updated/amended as necessary as work proceeds. Readers are therefore advised to periodically check for any updates or revisions. The Centre and its collaborators/partners have obtained data from sources believed to be reliable and have made every reasonable effort to ensure its accuracy. However, the Centre and its collaborators/partners cannot assume responsibility for errors and omissions in the data nor in the documentation accompanying them. 2 CONTENTS A PROJECT INTRODUCTION Type of project Project name Description of mode type Technical specification Principal transport nodes Major associated developments Parent projects Country/location Current status B PROJECT BACKGROUND Principal project objectives Key enabling mechanisms Description of key enabling mechanisms Key enabling mechanisms timeline Main organisations involved Planning and environmental regime Outline of planning legislation Environmental statements Overview of public consultation Ecological mitigation Regeneration Ways of appraisal Complaints procedures Land acquisition C PRINCIPAL PROJECT CHARACTERISTICS Detailed description of route Detailed description of main -

Travel with the Metropolitan Museum of Art

BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB Travel with Met Classics The Met BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB May 9–15, 2022 Berlin with Christopher Noey Lecturer BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB Berlin Dear Members and Friends of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Berlin pulses with creativity and imagination, standing at the forefront of Europe’s art world. Since the fall of the Wall, the German capital’s evolution has been remarkable. Industrial spaces now host an abundance of striking private art galleries, and the city’s landscapes have been redefined by cutting-edge architecture and thought-provoking monuments. I invite you to join me in May 2022 for a five-day, behind-the-scenes immersion into the best Berlin has to offer, from its historic museum collections and lavish Prussian palaces to its elegant opera houses and electrifying contemporary art scene. We will begin with an exploration of the city’s Cold War past, and lunch atop the famous Reichstag. On Museum Island, we -

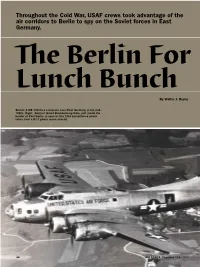

Throughout the Cold War, USAF Crews Took Advantage of the Air Corridors to Berlin to Spy on the Soviet Forces in East Germany

Throughout the Cold War, USAF crews took advantage of the air corridors to Berlin to spy on the Soviet forces in East Germany. The Berlin For Lunch Bunch By Walter J. Boyne Below: A RB-17G flies a mission over West Germany in the mid- 1950s. Right: Berlin’s famed Brandenburg Gate, just inside the border of East Berlin, is seen in this 1954 surveillance photo taken from a B-17 photo recon aircraft. 56 AIR FORCE Magazine / July 2012 hree air routes to West Berlin well as navigation and landing aids, were The corridors also led to the success- were established after the end of established. Air support to the conference ful covert reconnaissance that was about World War II to give the Western went well, and the Western Allies assumed to begin. Allies air access to their garrisons this would continue as they established The history of the reconnaissance squad- in the former Nazi capital. their garrisons. rons destined to become corridor intel- TWhen the Soviet Union imposed its ligence collectors is intricate. Although blockade in 1948, these air routes be- An Intricate History American recon activity may have begun came famous as the vital corridors of the However, shortly after the conference earlier, the earliest hard evidence notes the Berlin Airlift, which enabled the British ended, the Soviets began to complain that establishment of a special secret Douglas and Americans to supply the beleaguered the Allies were flying outside the agreed A-26 Invader flight within the 45th Re- city. It is less well known that they were corridors and this would not be tolerated. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1987 BERLINART: 20 FILMS June 11 - September 5, 1987 BERLINART: 20 FILMS, the film component of The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition BERLINART: 1961-1987, reflects the integral role of film in the Berlin art community. Organized by Laurence Kardish, curator in the Department of Film, the thirteen programs include fiction and nonfiction works by more than twenty filmmakers. These films, made between 1971 and 1987, relate to various aspects of Berlin life. The filmmakers represented here have responded in a variety of ways to the cultural, political, and economic conditions resulting from Berlin's unique geographic position. They explore the psychological, spiritual, and social issues of contemporary life in Berlin, working in an environment supported by a progressive film and television academy, as well as alternative distributors and exhibitors. Federal and municipal grants and production money from German television have also attracted German and American filmmakers to West Berlin. BERLINART: 20 FILMS, beginning June 11 and continuing through September 5, 1987, opens with Helma Sanders-Brahms's romantic drama Laputa (1986), starring Sami Frey and Krystyna Janda. The film, in which Berlin is compared to the floating island Laputa in Swift's Gulliver's Travels, depicts the city as a transit station for the brief encounters of two foreign lovers. The peculiar geography, topography, and architecture of Berlin also figure strongly in Alfred Behrens's Images of Berlin's City Railway (1982), a poetic exploration of the vast, largely unused public transit that connects East and - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019-5486 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART - 2 - West Berlin; and Elf1 Mikesch's Macumba (1982), a mystery in which the city's haunting interior spaces seem to determine the actions and moods of the characters.