Developing Emergency Communication Strategies for Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jersey Industrial Complex Rancho Cucamonga, California

JERSEY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CALIFORNIA NOISE STUDY Prepared for: Ralph Karubian 11298 Jersey Boulevard, LLC 1801 South Mountain Avenue Monrovia, CA 91016 Prepared by: December 2020 Jersey Industrial Complex Noise Study JERSEY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX PROJECT RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CALIFORNIA Noise Study Table of Contents Page Project Description ........................................................................................................................... 1 Setting ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Overview of Sound Measurement ................................................................................................. 4 Sensitive Receptors .......................................................................................................................... 6 Project Site Setting ............................................................................................................................ 6 Regulatory Setting ............................................................................................................................ 8 Vibration Standards ....................................................................................................................... 11 Impact Analysis .............................................................................................................................. 12 Methodology and Significance Thresholds ............................................................................... -

Draft Environmental Impact Statement - Modification of the CONDOR 1 and CONDOR 2 Military Operations Areas (MOA), August 2009

Maine State Library Digital Maine Transportation Documents Transportation 8-1-2009 Draft Environmental Impact Statement - Modification of the CONDOR 1 and CONDOR 2 Military Operations Areas (MOA), August 2009 Maine Department of Transportation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs Draft Environmental Impact Statement – Modification of the Condor 1 and Condor 2 Military Operations Areas 104th Fighter Wing, Barnes Air National Guard Base, Westfield, MA Project No. ANG0956737 August 2009 Acronyms and Abbreviations 104 FW 104 Figher Wing MDIFW Maine Department of Inland AGL above ground level Fisheries and Wildlife AHAS Avian Hazard Advisory System MOA military operations area ANG Air National Guard MOU Memorandum of Understanding APE Area of Potential Effect MR_NMAP Military Operating Area and Range AQCR Air Quality Control Region Noise Model and Assessment AT Appalachian Trail Program ATC Air Traffic Control MSL mean sea level BAM Bird Avoidance Model MTR military training route BASH Bird Aircraft Strike Hazard NAAQS National Ambient Air Quality CAA Clean Air Act Standards CAP Combat Air Patrol NEPA National Environmental Policy CEQ Council on Environmental Quality Act CFR Code of Federal Regulations NHDES New Hampshire Department of CLNA Connecticut Lakes Natural Area Environmental Services CMR Combat Mission Ready NHNHB New Hampshire Natural Heritage CO Carbon Monoxide Bureau CWA Clean Water Act NHPA National Historic Preservation Act dB decibel NM nautical mile dBA A-weighted decibel NO2 nitrogen dioxide -

Suggestions for Expanding the Capabilities of the Emergency Alert System (Comments on EB Docket No. 04-296)

October 29, 2004 Suggestions for Expanding the Capabilities of the Emergency Alert System Peter K. Sheerin (Comments on EB Docket No. 04-296) 1121 Nimitz Lane Foster City, CA 94404 The FCC is currently soliciting comments about proposed changes to the Emergency Alert System [email protected] Existing disaster notification methods in common use within the U.S. include: • National Weather Radio All-Hazards alert system with county-specific alert coding • EAS alerts transmitted via AM and FM broadcast stations • EAS alerts transmitted via television broadcast stations • Community Civil-Defense siren systems For various technological and social reasons, I don’t believe that these warning channels are sufficient to notify enough of the public to preserve lives and avoid panic in any true large-scale disaster that would require specific responses from the public, such as evacuation or shelter-in-place. Therefore, these existing alert systems should be augmented with the use of modern technology to enable the dissemination of high-quality, concise alerts to the public by multiple, redundant methods, so as to ensure reception by the widest possible percentage of the population, no matter what their current activity. I believe a few new mandates need to be created in order to ensure that common electronic devices can participate in the expanded national/local alert system, and while such mandates may on the surface appear in direct conflict with the American ideals of competition and freedom of innovation, the particular technologies I believe should be used would be a very small, or even non-existent burden on the device manufacturers, and will even serve to enhance the business prospects of these device manufacturers and the broadcast and telecommunications industries that use the devices. -

Hawaii County Letter Re: Compliance with Conditions

William P. Kenoi BJ Leithead Todd layor Director Margaret K, Masanaga Deputy West Hnwaiq Office East Hawai'i ()ffice 74-5044 Ane Keohokalole Hwy 10l Pauahi Street, Suile 3 Kailua-Kona. Hawai'[ 96740 County of Hawai'i Phone {808) 323-4770 Hilo, Hawai'i 96720 Fax (808) 327-3563 Phone (808) 961-8288 PLANNING DEPARTMENT Fax (808) 961-8742 March 7, 2012 P'o t- Mr. Joe Vierra Belt Collins Hawaii Ltd. 2153 North King Street, Suite 200 rÿq Cÿ F:I Honolulu, HI 96819-4554 I C-o :::E "5. Dear Mr. Vierra: Applicant: The Newton Family Limited Partnership Docket No. A99-729 (SLU 1128) tad :ÿ7 Change of Zone Ordinance No. 06 27 (REZ 05-017) Subject: 2011 AnnualProgress Report Tax Map Key: 2-4-008: por. 033 This is to acknowledge receipt of your letters dated November 21, 201 l, containing annual progress reports in compliance with Condition No. 20 of Docket No. A99-729 and with Condition N of Change of Zone Ordinance No. 06 27 (REZ 05-017). Thank you for complying with these requirements. It is our understanding that the water commitment payment lequired by Condition D of Ordinance No. 06 27 was paid in 2006 but then returned to the applicant. Thus, the applicant has not complied with Condition D. Please immediately remit the water commitment payment to the Department of Water Supply. Once the applicant has complied with Condition D, an administrative time extension to secure final subdivisiun approval, as required by Condition E, can be granted. The next almual reports will be due on or before February 24, 2013. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. February 1964 United States - Canada Agreement on Civil Emergency Planning Hurricane Carla's Lessons Control of Food Supplies Exposed to Fallout Emergency Sanitation in Disaster Santa Fe Civil Defence System hICY EASURES RGANIZATION THE EMO NATIONAL DIGEST Published by the Emergency Measures Organization, Ottawa, Ont. -

Duane Arnold

50-331 DUANE ARNOLD SITE-SPECIFIC OFFSITE RADIOLOGICAL PREPAREDNESS ALERT NOTIFICATION SYSi QUALITY ASSURANCE VERIFICATION LTR.DTD. 1/18/90 9002060014 -1N0TICE-, THE ATTACHED FILES ARE OFFICIAL RE CORDS OF THE RECORDS & REPORTS MANAGEMENT BRANCH. THEY HAVE BEEN CHARGED TO YOU FO R A LIMITED IME PERIOD AND AMUST BE RETURNED TO THE RECORDS & ARCHIVES SERVICES SECION P1-122 WHITE FLIN LESE DN SEND DOCUMENTS CHAR GEl THROUGH THE MAIL. REMOVAL OF ANY PAGE(S) FROM DOCUMENT FOR REPRO DUCTION MUST BE REFERRED TO FILE PERSONNEL. -NOTICE- DUANE ARNOLD ENERGY CENTER SITE-SPECIFIC OFFSITE RADIOLOGICAL EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS ALERT AND NOTIFICATION SYSTEM QUALITY ASSURANCE VERIFICATION Prepared for Federal Emergency Management Agency Washington, D.C. 20472 Under Contract No. EMW-83-C-1217 September 14, 1989 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Identification 1 1. Site Information 1 2. Governments Within The 10-Mile Emergency Planning Zone 3 B. Scope Of Review 4 1. Emergency Plans For Offsite Response Organizations 4 2. Alert And Notification System Design Report 5 3. FEMA Evaluation Findings 5 II. FINDINGS FOR EVALUATION CRITERION E.6 6 A. Administrative Means Of Alerting (E.6.1, FEMA-REP-10) 7 B. Physical Means Of Alerting (E.6.2, FEMA-REP-10) 12 1. Sirens (E.6.2.1, FEMA-REP-10) 12 2. Special Alerting (E.6.2.4, FEMA-REP-10) 26 3. Institutional Alerting (E.6.2.4.2, FEMA-REP-10) 27 III. FINDINGS FOR EVALUATION CRITERION N.1 28 IV. FINDINGS FOR EVALUATION CRITERIA E.5, F.l, N.2, N.3, AND N.5 34 REFERENCE LIST 35 APPENDIX A: OSPM Topographical Profile Charts OSPM Topographical Input Data OSPM Siren Sound Pressure Level Input Data OSPM Meteorological Input Data OSPM Siren Sound Pressure Level Output Data APPENDIX B: Sample Size Determination Duane Arnold Energy Center Site-Specific Offsite Radiological Emergency Preparedness Alert And Notification System Quality Assurance Verification State Of Iowa Benton County Linn County I. -

A Case Study of a Tsunami Warning Simulation Exercise

Case Study of a Tsunami Warning Simulation Exercise from a Regional Perspective – “Lessons Learned from Each Event – Real or Hoax” TARNS 3rd Workshop February 6-8, 2007 Chonlapreuk Resort, Nakorn Nayok, Thailand Presented by Edward H. Young, Jr. Deputy Director, NOAA National Weather Service Pacific Region End-to-End Tsunami Early Warning System for Hawaii • The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) and the Hawaii Civil Defense System serves as an example of an “End-To-End” Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System. • An end to end system refers to the ability of the Tsunami Warning System to detect and disseminate tsunami information to the emergency management community and to the public for coastal evacuation as ordered by Civil Defense officials. End-to-End Tsunami Early Warning System for Hawaii • Hawaii State and County Civil Defense are Disaster Management Offices and by law, have the responsibility to prepare for and respond to natural and man-made technological emergencies and disasters. • OUR GOAL: SAVE LIVES AND MINIMIZE DAMAGE FROM DISASTER PTWCPTWC KEYKEY OPERATIONALOPERATIONAL ACTIVITIESACTIVITIES •• SEISMICSEISMIC DATADATA COLLECTIONCOLLECTION && ANALYSESANALYSES •• SEASEA LEVELLEVEL MEASUREMENTSMEASUREMENTS •• DECISIONDECISION--MAKINGMAKING PROCESSESPROCESSES •• MESSAGEMESSAGE CREATIONCREATION && DISSEMINATIONDISSEMINATION PTWCPTWC OPERATIONALOPERATIONAL GOALSGOALS •• FASTERFASTER •• MOREMORE ACCURATEACCURATE •• MOREMORE RELIABLERELIABLE Earthquake in Hawaii Region Timeline to Issue Initial Warning Bulletin Watchstanders First -

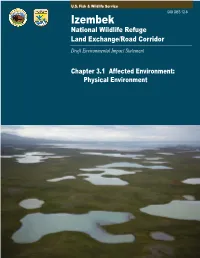

Chapter 3A Physical Environment

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service DOI DES 12-8 Izembek National Wildlife Refuge Land Exchange/Road Corridor Draft Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 3.1 Affected Environment: Physical Environment CHAPTER 3 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT ....................................................................................... 3-1 3.1 Physical Environment ............................................................................................. 3-1 3.1.1 Air Quality .................................................................................................. 3-1 3.1.1.1 Study Area ................................................................................... 3-1 3.1.1.2 Regulatory Framework and Pollutants of Concern ...................... 3-1 3.1.1.3 Existing Air Quality ..................................................................... 3-3 3.1.2 Climate ........................................................................................................ 3-5 3.1.2.1 Introduction .................................................................................. 3-5 3.1.2.2 Cold Bay Area.............................................................................. 3-5 3.1.2.3 Kodiak .......................................................................................... 3-8 3.1.2.4 Climate Patterns and Trends ........................................................ 3-9 3.1.3 Geology and Soils .................................................................................... -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. TS (Proikt#7072eion.miembCceeletofibedzume7tdoesmplAW 1q63 VOLUME .1 eeduse ebe.044g .11 ( s 11 àeuit s d4te dup471 docume or11. d Peat United States/Cana a route wills% du • dozmentdoitt9eekwee contenu leap Joint . du cohtinui" dIpmetee plki,4% eéaleinee "' --- e;Z jRcC Document ele Ref"enc List JRCC Meeting Nd. -

REMOTE OPERATION of the WEST COAST and ALASKA TSUNAMI WARNING CENTER 216 Alec H

ISSN 8755-6839 SCIENCE OF TSUNAMI HAZARDS The International Journal of The Tsunami Society Volume 20 Number 4 Published Electronically 2002 SECOND TSUNAMI SYMPOSIUM PAPERS - II LOCALLY GENERATED TSUNAMIS IN HAWAII: A LOW COST, REAL TIME WARNING SYSTEM WITH WORLD WIDE APPLICATIONS 177 Daniel A. Walker Haleiwa, Hawaii USA Robert K. Cessaro Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, Honolulu, Hawaii USA MAGNITUDE-DEPENDENT CORRECTION FOR MWP 187 Paul M. Whitmore and Thomas J. Sokolowski West Coast/Alaska Tsunami Warning Center, Palmer, Alaska USA Seiji Tsuboi Institute for Frontier Research on Earth Evolution, Yokosuka, Japan Barry Hirshorn Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, Ewa Beach, Hawaii USA A PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF TSUNAMI HAZARD AND RISK IN THE INDONESIAN REGION 193 Jack Rynn Center for Earthquake Research in Australia, Indooroopilly, Australia REMOTE OPERATION OF THE WEST COAST AND ALASKA TSUNAMI WARNING CENTER 216 Alec H. Medbery, Guy W. Urban, Paul M. Whitmore and Thomas J. Sokolowski West Coast/Alaska Tsunami Warning Center, Palmer, Alaska USA PREDICTIONS OF SLUMP GENERATED TSUNAMIS: THE JULY 17TH 1998 PAPUA NEW GUINEA EVENT 222 David R. Tappin, British Geological Survey, Nottingham, UK Philip Watts, Applied Fluids Engineering Inc, Long Beach, California, USA Gary M. McMurty, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii USA Yves LaFoy, Services des Mines et de I’Energie, Noumea, New Caledonia Takeshi Matsumoto, Japan Marine Science and Technology Center, Yokoshuka, Japan copyright @ 2002 THE TSUNAMI SOCIETY P. 0. Box 37970, Honolulu, HI 96817, USA WWW.STHJOURNAL.ORG OBJECTIVE: The Tsunami Society publishes this journal to increase and disseminate knowledge about tsunamis and their hazards. DISCLAIMER: Although these articles have been technically reviewed by peers, The Tsunami Society is not responsible for the veracity of any state- ment, opinion or consequences. -

Steve Parker Day Is Done

Steve Parker Day is Done November 21, 2020 – February 28, 2021 Brown Foundation Gallery & Vault November 21, 2020 – February 28, 2021 Steve Parker Day is Done Day is Done features sound sculptures by Austin-based artist Steve Parker. His work explores communal experiences that examine history, systems, and behavior. The exhibition features a new work inspired by Guy Taylor’s public performance of Taps each evening in downtown Galveston and the tradition being carried on by Constable Clint Wayne Brown. Parker’s site-responsive sculpture for Galveston is made from salvaged brass instrument bells that play a composition of collected recordings of the lyrics of the well-known Taps tune. This work reflects on its roots as a call to retire for the evening and metaphor for life and death. The exhibition also features Parker’s 2018 work Sirens in the second-floor vault, which reimagines the function of the contemporary civil defense siren. Rather than projecting conventional warning tones, Sirens plays intermittent recordings of songs of distress as a call to action. Steve Parker is an artist, musician, and curator in Austin, TX. He is the recipient of the Rome Prize, the Tito’s Prize, a Fulbright, and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. Parker works with salvaged musical instruments, amateur choirs, marching bands, urban bat colonies, flocks of grackles, and pedicab fleets to investigate how communal listening can provoke greater social awareness and responsibility. His projects include elaborate civic rituals for humans, animals, and machines; listening sculptures modeled after obsolete surveillance tools; and cathartic transportation symphonies for operators of cars, pedicabs, and bicycles. -

Environmental Assessment

Maine State Library Digital Maine Transportation Documents Transportation 2-1-2007 Environmental Assessment : Modifications of the Condor 1 and Condor 2 Military Operations Areas; Massachusetts Air National Guard 102nd Fighter Wing Otis Air National Guard Base, Falmouth, Massachusetts (Draft, February 2007) Maine Department of Transportation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/mdot_docs Draft ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT MODIFICATION OF THE CONDOR 1 AND CONDOR 2 MILITARY OPERATIONS AREAS Massachusetts Air National Guard 102nd Fighter Wing Otis Air National Guard Base Falmouth, Massachusetts February 2007 AIR NATIONAL GUARD READINESS CENTER ENVIRONMENTAL DIVISION FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ºF degrees Fahrenheit Ldn day-night average A-weighted µ/m3 microns per cubic meter sound level nd 102 FW 102 Fighter Wing Ldnmr onset rate-adjusted monthly day- AAMRL Armstrong Aerospace Medical night average A-weighted sound Research Laboratory level ACBT Air Combat Training LOWAT Low Altitude Awareness Training ACM Air Combat Maneuvering MAANG Massachusetts Air National Guard AFI Air Force Instruction MDEP Maine Department of AGL above ground level Environmental Protection AHAS Avian Hazard Advisory System MDIFW Maine Department of Inland AHC Advanced Handling Characteristics Fisheries and Wildlife ANG Air National Guard MOA military operations area AQCR Air Quality Control Region MOU Memorandum of Understanding APE Area of Potential Effect mph miles per hour AT Appalachian Trail MR_NMAP Military