WOOD ANATOMY of the BIGNONIACEAE, WI'ih a COMPARISON of TREES and Llanas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catálogo Chauá

Boletim Chauá 014 ISSN 2595-654X Manual de cultivo 1a edição Cybistax antisyphilitica (Mart.) Mart (Bignoniaceae) Setembro 2018 Nomes comuns: Ecologia: Brasil: caroba-braba, caroba-de-flor-verde, Dispersão: anemocórica1; ipê-verde, ipê-mandioca, ipê-da-várzea, aipê, Habitat: a espécie ocorre comumente no Cerrado cinco-chagas, ipê-mirim, ipê-pardo, sentido restrito, Cerradões e é comum em áreas caroba-do-campo, jacarandá1; alteradas e abertas. É encontrada ainda nas Peru: espeguilla, llangua, llangua-colorado, formações Montana e Submontana de Florestas orcco-huoranhuay, yangua, yangua-caspi, Estacionais e Florestas Ombrófilas1, 2, 12, 13, 14; 2 yangua-tinctoria ; Polinização: feita principalmente por abelhas de Paraguai: taiiy-hoby2. grande e médio porte15; Grupo ecológico: pioneira1, 12; Distribuição: Países: Argentina, Bolívia, Brasil, Equador, Utilidade: Paraguai, Peru e Suriname3, 4; A madeira é comumente utilizada na construção Estados no Brasil: Pará, Tocantins, Bahia, Ceará, civil. É citada a utilização das folhas na produção Maranhão, Piauí, Distrito Federal, Goiás, Mato de corantes e na medicina popular4. Grosso do Sul, Mato Grosso, Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul e Santa Catarina2; Características das Ecossistemas: Floresta Estacional Semidecidual, sementes e plântulas: Floresta Ombrófila Densa e Floresta Ombrófila Tipo de semente: ortodoxas9, 16; Mista 1, 2, 11, 12, 13, dos biomas Amazônia, Caatinga, 2,3-3,5 x 4-6 mm4; Cerrado, Mata-Atlântica e Pantanal 2; Tamanho: Sementes por kg: 40.68317; Nível de ameaça: Tipo de plântula: fanerocotiledonar epígea foliar (Figura 1F). Lista IUCN: Não especificado – NE; Lista nacionais: BRASIL: Não especificado 2; Recomendações para o Listas estaduais: Não consta. -

New Species and Combinations of Apocynaceae, Bignoniaceae, Clethraceae, and Cunoniaceae from the Neotropics

Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid 75 (2): e071 https://doi.org/10.3989/ajbm.2499 ISSN: 0211-1322 [email protected], http://rjb.revistas.csic.es/index.php/rjb Copyright: © 2018 CSIC. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-nc) Spain 4.0 License. New species and combinations of Apocynaceae, Bignoniaceae, Clethraceae, and Cunoniaceae from the Neotropics Juan Francisco Morales 1,2,3 1 Missouri Botanical Garden 4344 Shaw Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63110, USA. 2 Bayreuth Center of Ecology and Environmental Research (BayCEER), University of Bayreuth, Universitätstrasse 30, 95447 Bayreuth, Germany. 3 Doctorado en Ciencias Naturales para el Desarrollo (DOCINADE), Universidad Estatal a Distancia, 474–2050 Montes de Oca, Costa Rica. [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8906-8567 Abstract. Mandevilla arenicola J.F.Morales sp. nov. from Brazil, Clethra Resumen. Se describen e ilustran Mandevilla arenicola J.F.Morales secazu J.F.Morales sp. nov. from Costa Rica, and Weinmannia abstrusa sp. nov. de Brasil, Clethra secazu J.F.Morales sp. nov. de Costa Rica y J.F.Morales sp. nov. from Honduras are described and illustrated and Weinmannia abstrusa J.F.Morales sp. nov. de Honduras y se discuten their relationships with morphologically related species are discussed. sus relaciones con otras especies de morfología semejante. Se designan Lectotypes are designated for Anemopaegma tonduzianum Kraenzl., lectotipos para Anemopaegma tonduzianum Kraenzl., Bignonia Bignonia sarmentosa var. hirtella Benth. and Paragonia pyramidata var. sarmentosa var. hirtella Benth. and Paragonia pyramidata var. tomentosa tomentosa Bureau & K. Schum., as well as these last two names have Bureau & K.Schum., así como también se combinan estos dos últimos been combined. -

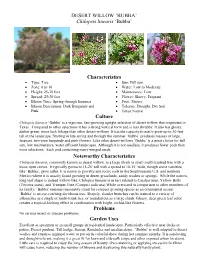

DESERT WILLOW 'BUBBA' Chilopsis Linearis 'Bubba' Characteristics

DESERT WILLOW ‘BUBBA’ Chilopsis linearis ‘Bubba’ Characteristics Type: Tree Sun: Full sun Zone: 6 to 10 Water: Low to Moderate Height: 25-30 feet Maintenance: Low Spread: 25-30 feet Flower: Showy, Fragrant Bloom Time: Spring through Summer Fruit: Showy Bloom Description: Dark Burgundy and Tolerate: Drought, Dry Soil Pink Texas Native Culture Chilopsis linearis ‘Bubba’ is a vigorous, fast-growing upright selection of desert willow that originated in Texas. Compared to other selections it has a strong vertical form and is less shrubby. It also has glossy, darker green, more lush foliage than other desert willows. It has the capacity to easily grow up to 30 feet tall in the landscape. Starting in late spring and through the summer ‘Bubba’ produces masses of large, fragrant, two-tone burgundy and pink flowers. Like other desert willows ‘Bubba’ is a great choice for full sun, low maintenance, water efficient landscapes. Although it is not seedless, it produces fewer pods than most selections. Each pod containing many winged seeds. Noteworthy Characteristics Chilopsis linearis, commonly known as desert willow, is a large shrub or small multi-trunked tree with a loose open crown. It typically grows to 15-25’ tall with a spread to 10-15’ wide, though some varieties, like ‘Bubba’, grow taller. It is native to gravelly and rocky soils in the Southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico where it is usually found growing in desert grasslands, sandy washes or springs. While the narrow, long leaf shape is indeed willow-like, Chilopsis linearis is in fact related to Catalpa trees, Yellow Bells (Tecoma stans), and Trumpet Vine (Campsis radicans).While oversized in comparison to other members of its family, ‘Bubba’ remains reasonably sized for compact growing spaces as an ornamental accent. -

Native Plants for Your Backyard

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Your Backyard Native plants of the Southeastern United States are more diverse in number and kind than in most other countries, prized for their beauty worldwide. Our native plants are an integral part of a healthy ecosystem, providing the energy that sustains our forests and wildlife, including important pollinators and migratory birds. By “growing native” you can help support native wildlife. This helps sustain the natural connections that have developed between plants and animals over thousands of years. Consider turning your lawn into a native garden. You’ll help the local environment and often use less water and spend less time and money maintaining your yard if the plants are properly planted. The plants listed are appealing to many species of wildlife and will look attractive in your yard. To maximize your success with these plants, match the right plants with the right site conditions (soil, pH, sun, and moisture). Check out the resources on the back of this factsheet for assistance or contact your local extension office for soil testing and more information about these plants. Shrubs Trees Vines Wildflowers Grasses American beautyberry Serviceberry Trumpet creeper Bee balm Big bluestem Callicarpa americana Amelanchier arborea Campsis radicans Monarda didyma Andropogon gerardii Sweetshrub Redbud Carolina jasmine Fire pink Little bluestem Calycanthus floridus Cercis canadensis Gelsemium sempervirens Silene virginica Schizachyrium scoparium Blueberry Red buckeye Crossvine Cardinal flower -

Trumpet Creeper (Campsis Radicans) Control Herbicide Options

Publication 20-86C October 2020 Trumpet Creeper (Campsis radicans) Control Herbicide Options Dr. E. David Dickens, Forest Productivity Professor; Dr. David Clabo, Forest Productivity Professor; and David J. Moorhead, Emeritus Silviculture Professor; UGA Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources BRIEF Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans), also known as cow itch vine, trumpet vine, or hummingbird vine, is in the Bignoniaceae family and is native to the eastern United States. Trumpet creeper is frequently found in a variety of southeastern United States forests and can be a competitor in pine stands. If not controlled, it can kill the trees it grows on by canopying over the crowns and not allowing adequate sunlight to get to the tree’s foliage for photo- synthesis. Trumpet creeper is a deciduous, woody vine that can “climb” trees up to 40 feet or greater heights (Photo 1) or form mats on shrubs or grows in clumps lower to the ground (Photo 2). The 1 to 4 inch long green leaves are pinnate, ovate in shape and opposite (Photo 3). The orange to red showy flowers are terminal cymes of 4 to 10 found on the plants during late spring into summer (Photo 4). Large (3 to 6 inches long) seed pods are formed on mature plants in the fall that hold hundreds of seeds (Photo 5). Trumpet creeper control is best performed during active growth periods from mid-June to early October in Georgia. If trumpet creeper has climbed up into a num- ber of trees, a prescribed burn or cutting the vines to groundline may be needed to get the climbing vine down to groundline where foliar active herbicides will be effective. -

Coleeae: Crescentieae: Oroxyleae

Gasson & Dobbins - Trees versus lianas in Bignoniaceae 415 Schenck, H. 1893. Beitriige zur Anatomie Takhtajan, A. 1987. Systema Magnoliophy der Lianen. In: A.F.W. Schimper (ed.): torum. Academia Scientiarum U.R.S.S., 1-271. Bot. Mitt. aus den Tropen. Heft Leningrad. 5, Teil2. Gustav Fischer, Jena. Wheeler, E.A., R.G. Pearson, C.A. La Spackman, W. & B.G.L. Swamy. 1949. The Pasha, T. Zack & W. Hatley. 1986. Com nature and occurrence of septate fibres in puter-aided Wood Identification. Refer dicotyledons. Amer. 1. Bot. 36: 804 (ab ence Manual. North Carolina Agricultural stract). Research Service Bulletin 474. Sprague, T. 1906. Flora of Tropical Africa. Willis, J. C. 1973. A dictionary of the flower Vol. IV, Sect. 2, Hydrophyllaceae to. Pe ing plants. Revised by H. K. Airy Shaw. daliaceae. XCVI, Bignoniaceae: 512-538. 8th Ed. Cambridge Univ. Press. Steenis, C.G.G.J. van. 1977. Bignoniaceae. Wolkinger, F. 1970. Das Vorkommen leben In Flora Malesiana I, 8 (2): 114-186. der Holzfasem in Striiuchem und Bliumen. Sijthoff & Noordhoff, The Netherlands. Phyton (Austria) 14: 55-67. Stem, W. L. 1988. Index Xylariorum 3. In Zimmermann, M.H. 1983. Xylem structure stitutional wood collections of the world. and the ascent of sap. Springer Verlag, IAWA Bull. n.s. 9: 203-252. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokyo. APPENDIX The species examined are listed below. The country or geographical region of origin is that from which the specimen came, not necessarily its native habitat. If the exact source of the specimen is not known, but the native region is, this is in parentheses. -

Podranea Ricasoliana.Pdf

Family: Bignoniaceae Taxon: Podranea ricasoliana Synonym: Pandorea ricasoliana (Tanfani) Baill. Common Name: pink trumpet vine Podranea brycei (N. E. Br.) Sprague Port St. Johns creeper Tecoma brycei N. E. Br. Zimbabwe creeper Tecoma mackenii W. Watson bubblegum-vine Tecoma ricasoliana Tanfani pandorea Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: HPWRA OrgData Designation: H(HPWRA) Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: HPWRA OrgData WRA Score 7 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 y 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 401 Produces -

Landscape Vines for Southern Arizona Peter L

COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND LIFE SCIENCES COOPERATIVE EXTENSION AZ1606 October 2013 LANDSCAPE VINES FOR SOUTHERN ARIZONA Peter L. Warren The reasons for using vines in the landscape are many and be tied with plastic tape or plastic covered wire. For heavy vines, varied. First of all, southern Arizona’s bright sunshine and use galvanized wire run through a short section of garden hose warm temperatures make them a practical means of climate to protect the stem. control. Climbing over an arbor, vines give quick shade for If a vine is to be grown against a wall that may someday need patios and other outdoor living spaces. Planted beside a house painting or repairs, the vine should be trained on a hinged trellis. wall or window, vines offer a curtain of greenery, keeping Secure the trellis at the top so that it can be detached and laid temperatures cooler inside. In exposed situations vines provide down and then tilted back into place after the work is completed. wind protection and reduce dust, sun glare, and reflected heat. Leave a space of several inches between the trellis and the wall. Vines add a vertical dimension to the desert landscape that is difficult to achieve with any other kind of plant. Vines can Self-climbing Vines – Masonry serve as a narrow space divider, a barrier, or a privacy screen. Some vines attach themselves to rough surfaces such as brick, Some vines also make good ground covers for steep banks, concrete, and stone by means of aerial rootlets or tendrils tipped driveway cuts, and planting beds too narrow for shrubs. -

LUẬN VĂN THẠC SĨ LÂM NGHIỆP Chuyên Ngành: Lâm Học

ĐẠI HỌC HUẾ TRƯỜNG ĐẠI HỌC NÔNG LÂM LÊ NGỌC TUẤN NGHIÊN CỨU HIỆN TRẠNG PHÂN BỐ VÀ KỸ THUẬT NHÂN GIỐNG NHẰM PHÁT TRIỂN NGUỒN GEN LOÀI CÂY QUAO (Dolichandrone spathacea (L.f.) K. Schum) TẠI TỈNH THỪA THIÊN HUẾ LUẬN VĂN THẠC SĨ LÂM NGHIỆP Chuyên ngành: Lâm học HUẾ - 2020 ĐẠI HỌC HUẾ TRƯỜNG ĐẠI HỌC NÔNG LÂM LÊ NGỌC TUẤN NGHIÊN CỨU HIỆN TRẠNG PHÂN BỐ VÀ KỸ THUẬT NHÂN GIỐNG NHẰM PHÁT TRIỂN NGUỒN GEN LOÀI CÂY QUAO (Dolichandrone spathacea (L.f.) K. Schum) TẠI TỈNH THỪA THIÊN HUẾ LUẬN VĂN THẠC SĨ LÂM NGHIỆP Chuyên ngành: Lâm học Mã số: 8620201 NGƯỜI HƯỚNG DẪN KHOA HỌC PGS.TS. ĐẶNG THÁI DƯƠNG HUẾ - 2020 i LỜI CAM ĐOAN Tôi xin cam đoan đề tài: “Nghiên cứu hiện trạng phân bố và kỹ thuật nhân giống phát triển nguồn gen loài cây Quao (Dolichandrone spathacea (L.f.) K. Schum) tại tỉnh Thừa Thiên Huế.” Các số liệu, kết quả trong luận án là trung thực và chưa được công bố. Nếu có kế thừa kết quả nghiên cứu của người khác thì đều được trích dẫn rõ nguồn gốc. Huế, tháng 5 năm 2020 Tác giả Lê Ngọc Tuấn ii LỜI CẢM ƠN Trong quá trình hoàn thành luận văn này tôi xin được bày tỏ lòng biết ơn chân thành và sâu sắc nhất tới Trường Đại học Nông lâm Huế, các Thầy giáo Trường Đại học Nông Lâm Huế đã tạo mọi điều kiện thuận lợi trong việc học tập, phương pháp nghiên cứu, cơ sở lý luận… Đặc biệt là thầy giáo PGS.TS. -

Mangroves: Unusual Forests at the Seas Edge

Tropical Forestry Handbook DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-41554-8_129-1 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Mangroves: Unusual Forests at the Seas Edge Norman C. Dukea* and Klaus Schmittb aTropWATER – Centre for Tropical Water and Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia bDepartment of Environment and Natural Resources, Deutsche Gesellschaft fur€ Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, Quezon City, Philippines Abstract Mangroves form distinct sea-edge forested habitat of dense, undulating canopies in both wet and arid tropic regions of the world. These highly adapted, forest wetland ecosystems have many remarkable features, making them a constant source of wonder and inquiry. This chapter introduces mangrove forests, the factors that influence them, and some of their key benefits and functions. This knowledge is considered essential for those who propose to manage them sustainably. We describe key and currently recommended strategies in an accompanying article on mangrove forest management (Schmitt and Duke 2015). Keywords Mangroves; Tidal wetlands; Tidal forests; Biodiversity; Structure; Biomass; Ecology; Forest growth and development; Recruitment; Influencing factors; Human pressures; Replacement and damage Mangroves: Forested Tidal Wetlands Introduction Mangroves are trees and shrubs, uniquely adapted for tidal sea verges of mostly warmer latitudes of the world (Tomlinson 1994). Of primary significance, the tidal wetland forests they form thrive in saline and saturated soils, a domain where few other plants survive (Fig. 1). Mangrove species have been indepen- dently derived from a diverse assemblage of higher taxa. The habitat and structure created by these species are correspondingly complex, and their features vary from place to place. For instance, in temperate areas of southern Australia, forests of Avicennia mangrove species often form accessible parkland stands, notable for their openness under closed canopies (Duke 2006). -

Landa Park Tree Management Plan

PARKS AND RECREATION DEPARTMENT Landa Park Tree Maintenance Plan CITY OF NEW BRAUNFELS PARKS AND RECREATION DEPARTMENT Mission statement Our mission is to afford diverse opportunities and access for all residents and visitors through innovative programs and facilities, open space preservation and economic enhancement. Vision Statement Our Vision statement is to enhance the well being of our community through laughter, play, conservation and discovery. TABLE OF CONTENTS LANDA PARK TREE MAINTENANCE PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..………………………..……………..………………………… Page 1 HISTORY ……………………………………………………………………………….…... Page 1 BENEFITS OF TREES………………………………….………………………................Page 2 2015 MANAGEMENT GOALS……………………………………………………………. Page 3 SUMMARY OF MAINTENANCE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LANDA PARK……... Page 5 LANDA PARK TREE INVENTORY ………………………………………..…………….. Page 8 LANDA PARK FORESTRY STRATEGIES…………………………………………..…. Page 11 Management Zones………………………………………………............................ Page 11 Maintenance Guidelines ………………………………………............................... Page 11 Tree Specific Issues…………………………………………………........................ Page 15 Tree Protection……………………………………………………….….................... Page 16 Tree Planting Plan…………………………………………….………...................... Page 17 Species Diversity and Selection…………………………………............................ Page 17 Stem Density………………………………………………………............................ Page 19 Planting in Specific Locations…………………………………….………………….. Page 21 Outreach……………………………………………………………........................... Page 21 Education………………………………………………………………...................... -

A Preliminary List of the Vascular Plants and Wildlife at the Village Of

A Floristic Evaluation of the Natural Plant Communities and Grounds Occurring at The Key West Botanical Garden, Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida Steven W. Woodmansee [email protected] January 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to CarolAnn Sharkey Key West Botanical Garden 5210 College Road Key West, Florida 33040 and Kate Marks Heritage Preservation 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 1200 Washington DC 20005 Introduction The Key West Botanical Garden (KWBG) is located at 5210 College Road on Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida. It is a 7.5 acre conservation area, owned by the City of Key West. The KWBG requested that The Institute for Regional Conservation (IRC) conduct a floristic evaluation of its natural areas and grounds and to provide recommendations. Study Design On August 9-10, 2005 an inventory of all vascular plants was conducted at the KWBG. All areas of the KWBG were visited, including the newly acquired property to the south. Special attention was paid toward the remnant natural habitats. A preliminary plant list was established. Plant taxonomy generally follows Wunderlin (1998) and Bailey et al. (1976). Results Five distinct habitats were recorded for the KWBG. Two of which are human altered and are artificial being classified as developed upland and modified wetland. In addition, three natural habitats are found at the KWBG. They are coastal berm (here termed buttonwood hammock), rockland hammock, and tidal swamp habitats. Developed and Modified Habitats Garden and Developed Upland Areas The developed upland portions include the maintained garden areas as well as the cleared parking areas, building edges, and paths.