RCN Nursing History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

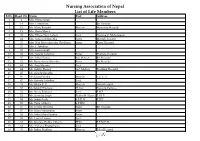

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Lawrlwytho'r Atodiad Gwreiddiol

Operational services structure April 2021 14/04/2021 Operational Leadership Structures Director of Operations Director of Nursing & Quality Medical Director Lee McMenamy Joanne Hiley Dr Tessa Myatt Medical Operations Operations Clinical Director of Operations Deputy Director of Nursing & Deputy Medical Director Hazel Hendriksen Governance Dr Jose Mathew Assistant Clinical Director Assistant Director of Assistant Clinical DWiraerctringor ton & Halton Operations Corporate Corporate Lorna Pink Assistant Assistant Director Julie Chadwick Vacant Clinical Director of Nursing, AHP & Associate Clinical Director Governance & Professional Warrington & Halton Compliance Standards Assistant Director of Operations Assistant Clinical Director Dr Aravind Komuravelli Halton & Warrington Knowsley Lee Bloomfield Claire Hammill Clare Dooley Berni Fay-Dunkley Assistant Director of Operations Knowsley Associate Medical Director Nicky Over Assistant Clinical Director Allied Health Knowsley Assistant Director of Sefton Professional Dr Ashish Kumar AssiOstapenrta Dtiironesc tKnor oofw Oslpeeyr ations Sara Harrison Lead Nicola Over Sefton James Hester Anne Tattersall Assistant Clinical Director Associate Clinical Director Assistant Director of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients St Helens Operations Sefton Debbie Tubey Dr Raj Madgula AssistanAt nDniree Tcatttore ofrs aOllp erations Head of St Helens & Knowsley Inpatients Safeguarding Tim McPhee Assistant Clinical Director Sarah Shaw Assistant Director of Associate Medical Director Operations St Helens Mental Health -

THE DEVELOPMENT of NURSING EDUCATION in the ENGLISH-SPEAKING CARIBBEAN ISLANDS by PEARL I

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NURSING EDUCATION IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING CARIBBEAN ISLANDS by PEARL I. GARDNER, B.S.N., M.S.N., M.Ed. A DISSERTATION IN HIGHER EDUCATION Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Approved Accepted Dean of the Graduate School August, 1993 ft 6 l^yrr^7^7 801 J ,... /;. -^o ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS C?^ /c-j/^/ C^ ;^o.^^ I would like to thank Dr. Clyde Kelsey, Jr., for his C'lp '^ ^unflagging support, his advice and his constant vigil and encouragement in the writing of this dissertation. I would also like to thank Dr. Patricia Yoder-Wise who acted as co-chairperson of my committee. Her advice was invaluable. Drs. Mezack, Willingham, and Ewalt deserve much praise for the many times they critically read the manuscript and gave their input. I would also like to thank Ms. Janey Parris, Senior Program Officer of Health, Guyana, the government officials of the Caribbean Embassies, representatives from the Caribbean Nursing Organizations, educators from the various nursing schools and librarians from the archival institutions and libraries in Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica. These individuals agreed to face-to-face interviews, answered telephone questions and mailed or faxed information on a regular basis. Much thanks goes to Victor Williams for his computer assistance and to Hannelore Nave for her patience in typing the many versions of this manuscript. On a personal level I would like to thank my niece Eloise Walters for researching information in the nursing libraries in London, England and my husband Clifford for his belief that I could accomplish this task. -

Design and Implementation of Health Information Systems

Design and implementation of health information systems Edited by Theo Lippeveld Director of Health Information Systems, John Snow Inc., Boston, MA, USA Rainer Sauerborn Director of the Department of Tropical Hygiene and Public Health, University of Heidelberg, Germany Claude Bodart Project Director, German Development Cooperation, Manila, Philippines World Health Organization Geneva 2000 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Design and implementation of health information systems I edited by Theo Lippeveld, Rainer Sauerborn, Claude Bodart. 1.1nformation systems-organization and administration 2.Data collection-methods I.Lippeveld, Theo II.Sauerborn, Rainer III.Bodart, Claude ISBN 92 4 1561998 (NLM classification: WA 62.5) The World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its pub lications, in part or in full. Applications and enquiries should be addressed to the Office of Publi cations, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, which will be glad to provide the latest information on any changes made to the text, plans for new editions, and reprints and translations already available. © World Health Organization 2000 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Health Or ganization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Explorations in Family Nursing

Explorations in Family Nursing The continuing shift in health care provision from hospital into the community places an increasing burden on the family as the primary source of care. Explorations in Family Nursing looks at how nurses can adopt a more collaborative approach to working with families both to facilitate their task as carers and to promote the health and well-being of the whole family. The first part of the book explores the theoretical underpinnings of family nursing, drawing insights from family therapy and systems theory and looks for a working definition of the family which is inclusive of the varied family forms encountered in contemporary society. The book goes on to establish the principles of family nursing explaining the process of making assessments, planning interventions and evaluating progress. Chapters on caring for chronically and terminally ill children, patients in intensive care, adolescents’ problems, frail elderly people and children with learning disabilities demonstrate the scope for applying family nursing strategies widely both in the community and in hospital. The book concludes with an evaluation of the opportunties, limitations and challenges which family nursing presents for nurses in the 1990s. Explorations in Family Nursing is of interest to practitioners at specialist and advanced levels and to students from Diploma to postgraduate degree programmes. Challenging nurses to adopt a more collaborative approach to care, this book makes a timely and relevant contribution to the development of nursing practice. Dorothy A.Whyte is Senior Lecturer in Nursing Studies at Edinburgh University. Explorations in Family Nursing Edited by Dorothy A.Whyte London and New York First published 1997 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. -

Evaluation of Hospital Information System in the Northern Province in South Africa

EVALUATION OF HOSPITAL INFORMATION SYSTEM IN THE NORTHERN PROVINCE IN SOUTH AFRICA “ Using Outcome Measures” Report prepared for the HEALTH SYSTEMS TRUST By Nolwazi Mbananga Rhulani Madale Piet Becker THE MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF SOUTH AFRICA PRETORIA May 2002 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Department of Health and Welfare in the Northern Province is acknowledged for its mandate to conduct this study and its support of the project throughout. The project Team is recognised for its great efforts in developing the project proposal and obtaining the necessary funding to conduct the study, without which it would not have been possible. The project team members; Dr Jeremy Wyatt, Dr LittleJohns, Dr Herbst, Dr Zwarenstein, Dr Power, Dr Rawlinson, Dr De Swart, Dr P Becker, Ms Madale and others played a key role in maintaining the scientific rigour for the study and their dedication is appreciated. The MEDUNSA Community Health in the Northern Province is credited for the direction and support it provided during the early stages of project development, planning and implementation. It is important to explain that Ms Mbananga conducted the qualitative component of the study as a Principal investigator while she and Dr Becker were called upon to take over the quantitative component of the study and joined at the stage of post implementation data collection. The financial support that was provided by the Health Systems Trust and the Medical Research Council is highly valued this project could not have been started and successfully completed without it. We cannot forget our secretaries: Emily Gomes and Alta Hansen who assisted us in transcribing data. -

The Matron's Handbook

The matron’s handbook For aspiring and experienced matrons Updated July 2021 Contents Foreword........................................................................................ 2 Introduction .................................................................................... 4 The matron’s key roles................................................................... 6 1. Inclusive leadership, professional standards and accountability 8 2. Governance, patient safety and quality .................................... 12 3. Workforce planning and resource management ...................... 17 4. Patient experience and reducing health inequalities ................ 22 5. Performance and operational oversight ................................... 24 6. Digital and information technology ........................................... 27 7. Education, training and development ....................................... 33 8. Research and development ..................................................... 36 9. Collaborative working and clinical effectiveness ...................... 37 10. Service improvement and transformation .............................. 40 Appendix: The matron’s developmental framework and competencies............................................................................... 43 Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 51 1 | Contents Foreword Matrons are vital to delivering high quality care to patients and their relatives across the NHS and the wider health and care sector. They -

Divisional Structure - University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust – As at 1 July 2021

Divisional structure - University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust – as at 1 July 2021 Chief operating officer Joe Teape Division A Division B Division C Division D DCD – Andrew Webb DCD – Trevor Smith DCD – Freya Pearson DCD – David Higgs DDO – Greg Chapple DDO – Gavin Hawkins DDO – Martin De Sousa DHN/P – Rachel Davies DHN/P – Sarah Herbert DDO – Jacqui McAfee DHN/P – Louisa Green DHN/P – Natasha Watts Acuity Matron – Karen Hill DR&DL – Fraser Cummings DoM – Suzanne Cunningham DR&DL – Boyd Ghosh DR&DL – Bhaskar Somani DFM – John Light DR&DL – Luise Marino DFM – Alex Mawers (Interim) DS&BDM – Alison Gray DFM – Wayne Rogers DFM – Emma Hawkins DS&BDM – Adam Wells HRBP – Emma Watts DS&BDM – Dan Jeffery DS&BDM – Victoria Kearney HRBP – Rachel Dore HRBP – Rachel Dore (covering until replacement) Care groups HRBP – Katie Dunman (nee Molloy) Care groups Cancer care: Care groups Care groups Surgery: CGCL – Tim Iveson Women and newborn: Cardiovascular and thoracic: CGCL – John Knight CGM – Collette Byelong CGCL – Sarah Walker CGCL – Edwin Woo CGM – Justin Sanders (from 5/7/21) A/CGM – awaiting appointment CGM – Fiona Lawson CGM – Fiona Liddell A/CGM – Jon Watson Matron – Jenny Milner IP & Theatres Matron – Carol Gosling ACGM – Juliet Thomas A/CGM – Erin Flahavan Matron – Steph Churchill OP Matron – Karen Elkins Matron – Jenny Dove Neonatal Matron – Andrea Robson (interim) Matron – Kerry Rayner Matron – Julia Tonks Matron – Georgina Kirk Angie Ansell (from 12/7/21) Emergency medicine: Matron - Jean-Paul Evangelista Matron – Jo Rigby CGCL -

The Lost Heroes of Nursing

The lost heroes of nursing Thompson , D. R. (2019). The lost heroes of nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(11), 2267-2269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14145 Published in: Journal of Advanced Nursing Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright Humana Press. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:25. Sep. 2021 Editorial The lost heroes of nursing David R Thompson PhD RN FRCN FAAN FESC Professor of Nursing School of Nursing and Midwifery Queen’s University Belfast Belfast United Kingdom Correspondence: Professor David R Thompson, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queen’s University Belfast, Medical Biology Centre, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 7BL, United Kingdom E‐mail: [email protected] ORCiD: 0000‐0001‐8518‐6307 1 A new book covering the first 85 years of DNA and culminating with the discovery of the double helix by James Watson and Francis Crick recounts how this was only possible because of the pioneering work of many others, often unknown or forgotten (Williams, 2019). -

The Case of Modern Matrons in the English NHS

The dynamics of professions and development of new roles in public services organizations: The case of modern matrons in the English NHS Abstract This study contributes to research examining how professional autonomy and hierarchy impacts upon the implementation of policy designed to improve the quality of public services delivery through the introduction of new managerial roles. It is based on an empirical examination of a new role for nurses - modern matrons - who are expected by policy makers to drive organizational change aimed at tackling health care acquired infections [HCAI] in the National Health Service [NHS] within England. First, we show that the changing role of nurses associated with their ongoing professionalisation limit modern matron‟s influence over their own ranks in tackling HCAI. Second, modern matrons influence over doctors is limited. Third, government policy itself appears inconsistent in its support for the role of modern matrons. Modern matrons‟ attempts to tackle HCAI appear more effective where infection control activity is situated in professional practice and where modern matrons integrate aspirations for improved infection control within mainstream audit mechanisms in a health care organization. Key words: professions, NHS, modern matrons, health care acquired infections Introduction The organization and management of professional work remains a significant area of analysis (Ackroyd, 1996; Freidson, 2001; Murphy, 1990; Reed, 1996). It is argued that professional autonomy and hierarchy conflict with bureaucratic and managerial methods of organizing work, especially attempts at supervision (Broadbent and Laughlin, 2002; Freidson, 2001; Larson, 1979). Consequently, the extension of managerial prerogatives and organizational controls are seen to challenge the autonomy, legitimacy and power of professional groups (Clarke and Newman, 1997; Exworthy and Halford, 1999). -

Interventions to Reduce Unplanned Hospital Admission:A Series of Systematic Reviews Page 3

Interventions to reduce unplanned hospital admission: a series of systematic reviews Funded by National Institute for Health Research Research for Patient Benefit no. PB-PG-1208-18013 Sarah Purdy, University of Bristol Shantini Paranjothy, Cardiff University Alyson Huntley, University of Bristol Rebecca Thomas, Cardiff University Mala Mann, Cardiff University Dyfed Huws, Cardiff University Peter Brindle, NHS Bristol Glyn Elwyn, Cardiff University Final Report June 2012 Acknowledgements Advisory group Karen Bloor Senior research fellow, University of York Tricia Cresswell Deputy medical director of NHS North East Helen England Vice chair of the South of England Specialised Commissioning Group and chairs the Bristol Research and Development Leaders Group Martin Rowland Chair in Health Services Research, University of Cambridge Will Warin Professional Executive Committee Chair, NHS Bristol. Frank Dunstan Chair in Medical Statistics, Department of Epidemiology, Cardiff University Patient & public involvment group In association with Hildegard Dumper Public Involvement Manager at Bristol Community Health With additional support from Rosemary Simmonds Research associate University of Bristol Library support Lesley Greig and Stephanie Bradley at the Southmead Library & Information Service, Southmead Hospital, Westbury-on-Trym, Bristol and South Plaza library, NHS Bristol and Bristol Community Health, South Plaza, Marlborough Street, Bristol. Additional support David Salisbury assistance with paper screening. Funding This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research, Research for Patient Benefit programme (grant PB-PG-1208-18013). This report presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. -

70 NHS Years: a Celebration of 70 Influential Nurses and Midwives

0 A celebration of 7 influential nurses NHS YEARS20 and midwives from 1948 to 18 In partnership with Seventy of the most influential nurses and midwives: 1948-2018 nursingstandard.com July 2018 / 3 0 7 years of nursing in the NHS Inspirational nurses and midwives who helped to shape the NHS Jane Cummings reflects on the lives of 70 remarkable As chief nursing officer for England, I am delighted figures whose contributions to nursing and to have contributed to this publication on behalf of midwifery are summarised in the following profiles, the CNOs in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and on the inspiration they provide as the profession identifying some of the most influential nurses and Jane Cummings meets today’s challenges midwives who have made a significant impact across chief nursing officer the UK and beyond. for England I would like to give special thanks to the RCNi As a nurse, when I visit front-line services and and Nursing Standard, who we have worked in meet with staff and colleagues across the country partnership with to produce this important reflection I regularly reflect on a powerful quote from the of our history over the past 70 years, and to its American author and management expert Ken sponsor Impelsys. Blanchard: ‘The key to successful leadership today is influence, not authority.’ Tireless work to shape a profession I am a firm believer that everyone in our Here you will find profiles of 70 extraordinary profession, whatever their role, wherever they work, nursing and midwifery leaders. Many of them have has the ability to influence and be influenced by the helped shape our NHS.