Down and Online in Amsterdam Zuidoost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retrospective Analysis of Water Management in Amsterdam, the Netherlands

water Article Retrospective Analysis of Water Management in Amsterdam, The Netherlands Sannah Peters 1,2, Maarten Ouboter 1, Kees van der Lugt 3, Stef Koop 2,4 and Kees van Leeuwen 2,4,* 1 Waternet (Public Water Utility of Amsterdam and Regional Water Authority Amstel, Gooi and Vecht), P.O. Box 94370, 1090 GJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (M.O.) 2 Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, Princetonlaan 8a, 3508 TC Utrecht, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 World Waternet, P.O. Box 94370, 1090 GJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 KWR Water Research Institute, P.O. Box 1072, 3430 BB Nieuwegein, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The capital of The Netherlands, Amsterdam, is home to more than 800,000 people. Devel- opments in water safety, water quality, and robust water infrastructure transitioned Amsterdam into an attractive, economically healthy, and safe city that scores highly in the field of water management. However, investments need to be continued to meet future challenges. Many other cities in the world have just started their transition to become water-wise. For those cities, it is important to assess current water management and governance practices, in order to set their priorities and to gain knowledge from the experiences of more advanced cities such as Amsterdam. We investigate how Amsterdam’s water management and governance developed historically and how these lessons can be used to further improve water management in Amsterdam and other cities. This retrospective analysis starts at 1672 and applies the City Blueprint Approach as a baseline water management assessment. -

The Amsterdam Treasure Room the City’S History in Twenty-Four Striking Stories and Photographs

The Amsterdam Treasure Room The city’s history in twenty-four striking stories and photographs Preface Amsterdam’s history is a treasure trove of stories and wonderful documents, and the Amsterdam City Archives is its guardian. Watching over more than 50 kilometers of shelves with old books and papers, photographs, maps, prints and drawings, and housed in the monumental De Bazel building, the archive welcomes everyone to delve into the city’s rich history. Wander through the Treasure Room, dating from 1926. Watch an old movie in our Movie Theatre. Find out about Rembrandt or Johan Cruyff and their times. Marvel at the medieval charter cabinet. And follow the change from a small city in a medieval world to a world city in our times. Bert de Vries Director Treasure Room Amsterdam City Archives 06 05 04 B 03 02 01 08 09 10 Floor -1 C 11 A 12 E 06 F D 05 0 -2 04 03 H 02 G 08 01 09 10 I Floor -2 11 I 12 J I K A D L 0 -2 4 Showcases Floor -1 Showcases Floor -2 The city’s history The city’s history seen by photographers in twelve striking stories 07 01 The first photographs 01 The origins of Amsterdam 08 of Amsterdam Praying and fighting 02 Jacob Olie 02 in the Middle Ages The turbulent 03 Jacob Olie 03 sixteenth century An immigrant city 04 George Hendrik Breitner 04 in the Dutch Golden Age 05 Bernard F. Eilers 05 Amsterdam and slavery Photography studio 06 Merkelbach 06 Foundlings in a waning city Amsterdam Zoo 07 Frits J. -

Chrono- and Archaeostratigraphy and Development of the River Amstel: Results of the North/South Underground Line Excavations, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw |94 – 4 | 333–352 | 2015 doi:10.1017/njg.2014.38 Chrono- and archaeostratigraphy and development of the River Amstel: results of the North/South underground line excavations, Amsterdam, the Netherlands P. Kranendonk1,S.J.Kluiving2,3,4,∗ & S.R. Troelstra5,6 1 Office for Monuments & Archaeology (Bureau Monumenten en Archeologie), Amsterdam 2 GEO-LOGICAL Earth Scientific Research & Consultancy, Delft 3 VU University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Studies, Amsterdam 4 VU University, Faculty of Earth & Life Sciences, Amsterdam 5 VU University, Faculty of Earth & Life Sciences, Earth & Climate Cluster, Amsterdam 6 NCB Naturalis, Leiden ∗ Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 28 May 2014, accepted: 2 November 2014 Abstract Since 2003 extensive archaeological research has been conducted in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, connected with the initial phase of the new underground system (Noord/Zuidlijn). Research has mainly focused on two locations, Damrak and Rokin, in the centre of Medieval Amsterdam. Both sites are situated around the (former) River Amstel, which is of vital importance for the origin and development of the city of Amsterdam. Information on the Holocene evolution of the river, however, is relatively sparse. This project has provided new evidence combining archaeological and geological data, and allowed the reconstruction of six consecutive landscape phases associated with the development of the River Amstel. The course of the present-day Amstel is the result of a complex interaction of processes that started with an early prehistoric tidal gully within the Wormer Member of the Naaldwijk Formation, including Late Neolithic (2400–2000 BC) occupation debris in its fill that was subsequently eroded. -

Neighbourhood Liveability and Active Modes of Transport the City of Amsterdam

Neighbourhood Liveability and Active modes of transport The city of Amsterdam ___________________________________________________________________________ Yael Federman s4786661 Master thesis European Spatial and Environmental Planning (ESEP) Nijmegen school of management Thesis supervisor: Professor Karel Martens Second reader: Dr. Peraphan Jittrapiro Radboud University Nijmegen, March 2018 i List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgment .................................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Liveability, cycling and walking .............................................................................................. 2 1.2. Research aim and research question ..................................................................................... 3 1.3. Scientific and social relevance ............................................................................................... 4 2. Theoretical background ................................................................................................................. 5 2.1. -

The Social Impact of Gentrification in Amsterdam

Does income diversity increase trust in the neighbourhood? The social impact of gentrification in Amsterdam Lex Veldboer & Machteld Bergstra, University of Amsterdam Paper presented at the RC21 Conference The Struggle to Belong: Dealing with Diversity in Twenty-first Century Urban Settings Session 10: Negotiating social mix in global cities Amsterdam, 7-9 July 2011 Lex Veldboer & Machteld Bergstra are researchers at the Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research, Kloveniersburgwal 48, 1012 CX Amsterdam [email protected] Does income diversity increase trust in the neighbourhood? The social impact of gentrification in Amsterdam Lex Veldboer & Machteld Bergstra, University of Amsterdam Abstract What happens when the residential composition of previously poor neighbourhoods becomes more socially mixed? Is the result peaceful co-existence or class polarization? In countries with neo-liberal policies, the proximity of different social classes in the same neighbourhood has led to tension and polarization. But what happens in cities with strong governmental control on the housing market? The current study is a quantitative and qualitative examination of how greater socio-economic diversity among residents affects trust in the neighbourhood in the Keynesian city of Amsterdam.1 Our main finding is that the increase of owner-occupancy in neighbourhoods that ten years ago mostly contained low-cost housing units has had an independent positive effect on neighbourhood trust. We further examined whether increased neighbourhood trust was associated with „mild gentrification‟ in two Amsterdam neighbourhoods. While this was partially confirmed, the Amsterdam model of „mild gentrification‟ is under pressure. 1 Amsterdam has a long tradition of public housing and rent controls. -

Amsterdam Web.Indd

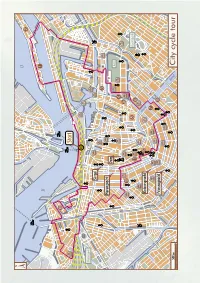

17 km City cycle tour 10.5 miles This tour will show you many of the different faces of Amsterdam. Of course you’ll see its historic centre with the famous canals where dur- ing the 17th century rich merchants built their stately homes. Next you’ll cycle through the Jordaan district, which used to be a working-class area in the early 17th century. Nowa- days it’s a pleasant neighbourhood with narrow streets and many little shops and pubs, an area which is greatly favoured by youngsters and yuppies. In the Jordaan you may want to visit some almshouses, dat- ing right back to the 17th century. In the Plantage district you’ll find the splendid urban villa’s of the ear- ly 19th century. And in the Spaar- dammer neighbourhood you‘ll see some beautiful examples of wor- king class apartment-buildings, de- signed by architects of the Amster- dam School in the early years of the 20th century. This architectural style made use of rounded shapes and brick ornaments to decorate the buildings. The buildings in the Spaarndammer- buurt are among the most important examples of the Amsterdam School. Last but not least you may be surprised by very modern houses on the banks of the River IJ, built in the late 20th century. Not only old warehouses have been con- verted into modern apartments, brand new residential areas have been built there as well, designed with a variety of architecture. On many occasions you may observe how modern buildings fit very well within the existing architecture. -

Banqueting Menu

BANQUETING MENU TO CREATE MEMORABLE MOMENTS WELCOME TO WALDORF ASTORIA AMSTERDAM Inspired by timeless Dutch history, Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam brings the legendary True Waldorf Service to a storied and unforgettable destination. Once wealthy patrician houses built during the Golden Age, Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam is situated on the UNESCO heritage protected Herengracht - “Gentlemen’s Canal”, the greatest of them all. This unparalleled location makes Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam the perfect venue for an unforgettable conference or celebration in the heart of Amsterdam. With all events catered by the exquisite cuisine of two Michelin Star Executive Chef Sidney Schutte, experience true luxury and enjoy the most memorable moments at this architectural monumental masterpiece, which brings historical charm together with world class amenities and personalized service. BREAKFAST BUFFET 36,00 per person HOT BREAKFAST Medium Poached Eggs Served with Mushrooms, Tomatoes, Smoked Bacon, Scrambled Eggs & Veal Sausage PASTRY SELECTION Croissant, Chocolate Croissant, Muffin & Baguette served with Farmers Butter, Seasonal Jams & Honey FRESH FRUIT Mixed Fruit Salad and Seasonal Berry Salad ORGANIC YOGHURT Plain, Low Fat & Smoothie BREAKFAST CEREALS Muesli, Cruesli, All Bran, Corn Flakes & Special K COLD TOPPINGS Smoked Salmon, Smoked Sirloin, Smoked Ham, Cooked Chicken, Goat Cheese, Reypenaar Cheese & Gouda Cheese DRINKS Coffee or Tea, Skimmed, Whole Fat, Soya or Chocolate Milk JUICES Fresh Orange or Grapefruit Juice Our Special “Van Nahmen” Juices: Apple -

Het Verkeer Verdeelt De Stad Tot Op Het Bot Ruimte, Doorstroming En Verbinden, Het Klinkt Goed Als Uitgangspunt Voor De Mo- Biliteit in De Drukte Van Amsterdam

Berichten uit de Westelijke Binnenstad Uitgave van De beleving van een kind A. van Wees distilleerderij De Ooievaar Dit blad biedt naast buurtinformatie Wijkcentrum Jordaan & Gouden Reael waarbij saamhorigheidsgevoel en begrip zich Op de uiterste noordwestpunt van de Jordaan, een platform waarop lezers hun visie op actuele jaargang 13 nummer 3 begon te ontwikkelen. De winnende staat al bijna 100 jaar A. van Wees distilleer- zaken kenbaar kunnen maken. Lees ook onze juni t/m augustus 2015 inzending van de verhalenwedstrijd derij De Ooievaar; de laatste ambachtelijke Webkrant: www.amsterdamwebkrant.nl de Jordaan door Henk de Hoogd Pagina 3 distilleerderij van Amsterdam Pagina 5 Haarlemmerbuurt Het verkeer verdeelt de stad tot op het bot Ruimte, doorstroming en verbinden, het klinkt goed als uitgangspunt voor de mo- biliteit in de drukte van Amsterdam. Maar schijn bedriegt: het verkeer verdeelt de stad tot op het bot. Een verkeersluwere Haarlemmerbuurt is goed voor de handel, zegt wethouder Pieter Litjens (VVD) die lof en kritiek oogstte. ‘Niet waar, dat kost omzet’, klinkt het uit de hoek van de Haarlemmerbuurtondernemers. T MI Amsterdam is gebouwd voor paard en wagen winkelstraatmanager Nel de Jager. Auto’s S en niet voor de 400.000 autobewegingen, en fietsers zijn nodig voor de klandizie. ‘De AN K J I 350.000 OV-reizigers en 1,1 miljoen fietsbe- Haarlemmerdijk is een boodschappenstraat. R wegingen, daarom wil Pieter Litjens wat aan Het is geen toeristengebied, zoals de Negen END het verkeer in de stad doen, zei hij half mei in Straatjes. Daar loop je alle straatjes door. De H O de Posthoornkerk aan de Haarlemmerstraat. -

Urban Europe.Indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag

omslag Urban Europe.indd | Sander Pinkse Boekproductie | 10/11/16 / 13:03 | Pag. All Pages In Urban Europe, urban researchers and practitioners based in Amsterdam tell the story of the European city, sharing their knowledge – Europe Urban of and insights into urban dynamics in short, thought- provoking pieces. Their essays were collected on the occasion of the adoption of the Pact of Amsterdam with an Urban Agenda for the European Union during the Urban Europe Dutch Presidency of the Council in 2016. The fifty essays gathered in this volume present perspectives from diverse academic disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences. Fifty Tales of the City The authors — including the Mayor of Amsterdam, urban activists, civil servants and academic observers — cover a wide range of topical issues, inviting and encouraging us to rethink citizenship, connectivity, innovation, sustainability and representation as well as the role of cities in administrative and political networks. With the Urban Agenda for the European Union, EU Member States of the city Fifty tales have acknowledged the potential of cities to address the societal challenges of the 21st century. This is part of a larger, global trend. These are all good reasons to learn more about urban dynamics and to understand the challenges that cities have faced in the past and that they currently face. Often but not necessarily taking Amsterdam as an example, the essays in this volume will help you grasp the complexity of urban Europe and identify the challenges your own city is confronting. Virginie Mamadouh is associate professor of Political and Cultural Geography in the Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies at the University of Amsterdam. -

5-Day Amsterdam City Guide a Preplanned Step-By-Step Time Line and City Guide for Amsterdam

5 days 5-day Amsterdam City Guide A preplanned step-by-step time line and city guide for Amsterdam. Follow it and get the best of the city. 5-day Amsterdam City Guide 2 © PromptGuides.com 5-day Amsterdam City Guide Overview of Day 1 LEAVE HOTEL Tested and recommended hotels in Amsterdam > Take Tram Line 2 or 5 to Hobbemastraat stop 09:00-10:30 Rijksmuseum World famous national Page 5 museum Take a walk to Concergebouw - 20’ 10:50-11:10 Concertgebouw World famous concert Page 5 hall Take a walk to Vondelpark - 10’ 11:20-11:50 Vondelpark Green oasis in the Page 6 center of the city Take a walk to Pieter Cornelisz Hooftstraat - 5’ 11:55-12:55 Pieter Cornelisz Hooftstraat Amsterdam's most Page 6 upscale and exclusive Lunch time shopping street Take a walk to City Canal Cruise boarding 14:00-15:30 City Canal Cruise Delightful experience Page 6 Take a walk to Heineken Experience - 20’ 15:50-17:50 Heineken Experience Very amusing, Page 7 interactive museum Take a walk to Leidseplein - 20’ 18:10-18:25 Leidseplein Amsterdam's tourist hub Page 7 END OF DAY 1 © PromptGuides.com 3 5-day Amsterdam City Guide Overview of Day 1 4 © PromptGuides.com 5-day Amsterdam City Guide Attraction Details 09:00-10:30 Rijksmuseum (Jan Luijkenstraat 1, Amsterdam) Opening hours: Daily: 9am - 6pm • Admission: 12.5 € THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW Admire the masterpieces on display (the Rijksmuseum is a national museum layout makes it easy to do a self-guided dedicated to arts, crafts, and history tour) The collection contains some seven million Pay attention to the impressive -

Progress and Stagnation of Renovation, Energy Efficiency, and Gentrification of Pre-War Walk-Up Apartment Buildings in Amsterdam

sustainability Article Progress and Stagnation of Renovation, Energy Efficiency, and Gentrification of Pre-War Walk-Up Apartment Buildings in Amsterdam Since 1995 Leo Oorschot and Wessel De Jonge * Heritage & Design, Section Heritage & Architecture, Department of Architectural Engineering & Technology, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology, Julianalaan 134, 2628BL Delft, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 February 2019; Accepted: 22 April 2019; Published: 5 May 2019 Abstract: Increasing the energy efficiency of the housing stock has been one of the largest challenges of the built environment in the Netherlands in recent decades. Parallel with the energy transition there is an ongoing revaluation of the architectural quality of pre-war residential buildings. In the past, urban renewal was traditionally based on demolition and replacement with new buildings. This has changed to the improvement of old buildings through renovation. Housing corporations developed an approach for the deep renovation of their housing stock in the period 1995–2015. The motivation to renovate buildings varied, but the joint pattern that emerged was quality improvement of housing in cities, focusing particularly on energy efficiency, according to project data files from the NRP institute (Platform voor Transformatie en Renovatie). However, since 2015 the data from the federation of Amsterdam-based housing associations AFWC (Amsterdamse Federatie Woningcorporaties) has shown the transformation of pre-war walk-up apartment buildings has stagnated. The sales of units are slowing down, except in pre-war neighbourhoods. Housing associations have sold their affordable housing stock of pre-war property in Amsterdam inside the city’s ring road. -

Leonardo Royal Hotel Amsterdam

Leonardo Royal Hotel Amsterdam Paul van Vlissingenstraat 24 I 1096 BK Amsterdam I E: [email protected] I T: +31 (0)20 250 0000 DESTINATION The Leonardo Royal Hotel Amsterdam welcomes you 490 11 420 to the Dutch city of canals and bridges. This 4-star FREE superior hotel is located directly at the metro station 24H »Overamstel«. Thanks to its convenient location and connection to two metro lines you can reach Amsterdam Central Station and Schiphol Airport within just a few minutes. Business travellers will also benefit from the direct underground connection to the Amsterdam RAI Exhibition and Conference Centre. ACCOMMODATION 490 rooms · 8 suites · air conditioning · free Wi-Fi · desk · telephone · TV · coffee & tea making facilities · minibar · laptop safe · hairdryer · 173 private parking spaces MEETING ROOMS The hotel offers 11 meeting and events spaces to accommodate your every need. Organize a success- ful meeting for up to 600 guests in our ballroom or choose a cosier setting in one of our other spaces. Our 900m² ballroom and its private terrace are the perfect canvas for your imagination and our dedicated Meetings and Events team will go above and beyond to make your event a success. Royal Hotel Amsterdam leonardo-hotels.com Length x Height Room Width in m in m Size in m² Size in ft² Amstel 1 18 x 17.6 6 316 3401 - 54 260 144 160 112 72 275 Amstel 2 18 x 14.4 6 259 2788 - 45 180 126 140 98 60 225 Amstel 3 18 x 17.6 6 316 3401 - 54 260 144 160 112 72 275 Amstel 1 & 2 18 x 32 6 576 6200 - 84 500 288 300 210 102