FAO-RAP 2014. Policy Measures for Micro, Small and Medium Food Processing Enterprises in the Asian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fermented Foods Fermented Foods

FERMENTED FOODS Fermented foods are among the oldest processed foods and have been eaten in almost all countries for millennia. They include fermented cereal products, alcoholic drinks, fermented dairy products and soybean products among many others. Details of the production of individual fermented foods are given in the following Technical Briefs: • Dairy ppproducts:products: Cheese making ; Ricotta Cheese Making ; Soured Milk and Yoghurt ; Yoghurt Incubator • Fruit and vegetable products: Gundruk (Pickled Leafy Vegetable) Banana Beer ; Grape Wine ; Toddy and Palm Wine ; Tofu and Soymilk Production ; Dry Salted Lime Pickle ; Dry Salted Pickled Cucumbers ; Green Mango Pickle ; Lime Pickle (Brined) ; Pickled Papaya ; Pickled Vegetables ; Fruit Vinegar ; Pineapple Peel Vinegar ; Coffee Processing . • Meat and fffishfish productsproducts: Fresh and Cured Sausages. This technical brief gives an overview of food fermentations and examples of fermented foods that are not included in the other technical briefs. Types of food fermentations Fermentations rely on the controlled action of selected micro-organisms to change the quality of foods. Some fermentations are due to a single type of micro-organism (e.g. wines and beers fermented by a yeast named ‘ Saccharomyces cerevisiae’ ), but many fermentations involve complex mixtures of micro-organisms or sequences of different micro-organisms. Fermented foods are preserved by the production of acids or alcohol by micro-organisms, and for some foods this may be supplemented by other methods (e.g. pasteurisation, baking, smoking or chilling). The subtle flavours and aromas, or modified textures produced by fermentations cannot be achieved by other methods of processing. These changes make fermentation one of the best methods to increase the value of raw materials. -

Microorganisms in Fermented Foods and Beverages

Chapter 1 Microorganisms in Fermented Foods and Beverages Jyoti Prakash Tamang, Namrata Thapa, Buddhiman Tamang, Arun Rai, and Rajen Chettri Contents 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.1.1 History of Fermented Foods ................................................................................... 3 1.1.2 History of Alcoholic Drinks ................................................................................... 4 1.2 Protocol for Studying Fermented Foods ............................................................................. 5 1.3 Microorganisms ................................................................................................................. 6 1.3.1 Isolation by Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Methods...................... 8 1.3.2 Identification: Phenotypic and Biochemical ............................................................ 8 1.3.3 Identification: Genotypic or Molecular ................................................................... 9 1.4 Main Types of Microorganisms in Global Food Fermentation ..........................................10 1.4.1 Bacteria ..................................................................................................................10 1.4.1.1 Lactic Acid Bacteria .................................................................................11 1.4.1.2 Non-Lactic Acid Bacteria .........................................................................11 -

SHIRLEYS UPDATED MENU 070219 Reduced2x

BREAKFAST • LUNCH SPECIALS • SNACKS BREAKFASTDINNER • DESSERTS• LUNCH SPECIALS • LATE NIGHT• SNACKS CATERDINNER TRAYS • DESSERTS • FUNCTIONS • LATE & EVENTSNIGHT CATER TRAYS • FUNCTIONS & EVENTS www.shirleyscoffeeshop.com shirleyscoffeeshopfanpage @shirleys_saipan shirleyscoffeeshop hirley’s Coffee Shop opened its doors in January of 1983 at the Downtown Hotel in Hagatna, Guam. It was my dream to combine Chinese and American food into a satisfying menu. The tastes and personalities of the customers who come through Shirley’s Coffee Shop doors are as different as their shoe sizes, but they all have one thing in common: they enjoy the best tast- ing combination of Oriental and American cooking for which Shirley’s is famous for. I personally invite you to come and bring your friends and family for a tasty treat that you will remember. Shirley’s Coffee Shop is acclaimed to have the best fried rice, pancakes, and ome- lets on Guam and Saipan by some very important people…our customers. Thank you for coming to Mama Shirley’s Coffee Shop! Sincerely, Mama Shirley Chamorro Sausage Cheese Omelet with Waffles A breakfast All-Day treat anytime! Breakfast Served with your choice of steamed white Upgrade your plain rice to any or brown rice, toast, pancakes, waffles, fried rice of your choice for fries, hashbrown or English Muffin. Served with your choice of steamed rice, Upgrade your plain rice to any $3.15 extra toast, pancakes, or English muffin. fried rice of your choice for $3.15 extra Eggs 'n Things Omelets Ham/Bacon/Spam/Spicy Spam Links/Corned -

SNACKS) Tahu Gimbal Fried Tofu, Freshly-Grounded Peanut Sauce

GUBUG STALLS MENU KUDAPAN (SNACKS) Tahu Gimbal Fried Tofu, Freshly-Grounded Peanut Sauce Tahu Tek Tek (v) Fried Tofu, Steamed Potatoes, Beansprouts, Rice Cakes, Eggs, Prawn Paste-Peanut Sauce Pempek Goreng Telur Traditional Fish Cakes, Egg Noodles, Vinegar Sauce Aneka Gorengan Kampung (v) Fried Tempeh, Fried Tofu, Fried Springrolls, Traditional Sambal, Sweet Soy Sauce Aneka Sate Nusantara Chicken Satay, Beef Satay, Satay ‘Lilit’, Peanut Sauce, Sweet Soy Sauce, Sambal ‘Matah’ KUAH (SOUP) Empal Gentong Braised Beef, Coconut-Milk Beef Broth, Chives, Dried Chili, Rice Crackers, Rice Cakes Roti Jala Lace Pancakes, Chicken Curry, Curry Leaves, Cinnamon, Pickled Pineapples Mie Bakso Sumsum Indonesian Beef Meatballs, Roasted Bone Marrow, Egg Noodles Tengkleng Iga Sapi Braised Beef Ribs, Spicy Beef Broth, Rice Cakes Soto Mie Risol Vegetables-filled Pancakes, Braised Beef, Beef Knuckles, Egg Noodle, Clear Beef Broth 01 GUBUG STALLS MENU SAJIAN (MAIN COURSE) Pasar Ikan Kedonganan Assorted Grilled Seafood from Kedonganan Fish Market, ‘Lawar Putih’, Sambal ‘Matah’, Sambal ‘Merah’, Sambal ‘Kecap’, Steamed Rice Kambing Guling Indonesian Spices Marinated Roast Lamb, Rice Cake, Pickled Cucumbers Sapi Panggang Kecap – Ketan Bakar Indonesian Spices Marinated Roast Beef, Sticky Rice, Pickled Cucumbers Nasi Campur Bali Fragrant Rice, Shredded Chicken, Coconut Shred- ded Beef, Satay ‘Lilit’, Long Beans, Boiled Egg, Dried Potato Chips, Sambal ‘Matah’, Crackers Nasi Liwet Solo Coconut Milk-infused Rice, Coconut Milk Turmeric Chicken, Pumpkin, Marinated Tofu & -

Bab I Bakpia Jagung; Diversifikasi Olahan Pangan Sebagai Salah Satu Cara Memberdayakan Perempuan Di Kecamatan Pajangan Kabupaten Bantul

BAB I BAKPIA JAGUNG; DIVERSIFIKASI OLAHAN PANGAN SEBAGAI SALAH SATU CARA MEMBERDAYAKAN PEREMPUAN DI KECAMATAN PAJANGAN KABUPATEN BANTUL Sugiharyanto, Taat Wulandari (e-mail: [email protected]), Anik Widiastuti A. Analisis Situasi Sebagian besar rakyat Indonesia makanan utamanya beras. Tidak heran kita selama ini masih mengimpor karena produk dalam negeri kurang mencukupi. Sementara lahan untuk menanam beras makin sempit. Padi adalah sejenis tanaman yang perlu banyak tenaga untuk merawatnya. Belum lagi jumlah air yang dibutuhkan. Sudah saat kita mencoba melakukan variasi atas makanan pokok kita. Selain beras, kita bisa variasi dengan jagung, ketela, kentang atau mie. Sepertinya roti-rotian belum banyak penggemarnya. Di Indonesia, makanan pengganti beras amat banyak. Yang paling mudah ditanam dan dibudi-dayakan adalah singkong baik singkong rambat atau singkong kaspe. Di daerah pesisir selatan pulau Jawa sudah ada masyarakat yang dulu makanan utamanya adalah gaplek yang terbuat dari singkong. Singkong kaspe memang amat fleksibel. Jenis makanan yang terbuat dari singkong amat beraneka. Misalnya: thiwul, gaplek, gethuk, keripik dan berbagai makan kecil lain, seperti bakpia jagung. Kecamatan Pajangan berada di sebelah Barat dari Ibukota Kabupaten Bantul. Kecamatan Pajangan mempunyai luas daerah 3.324,7590 Ha. Desa di wilayah administratif Kecamatan Pajangan: Desa Sendangsari, Desa Guwosari, dan Desa Triwidadi. Wilayah Kecamatan Pajangan berbatasan dengan : Utara : Kecamatan Kasihan dan Sedayu; Timur : Kecamatan Bantul; Selatan : Kecamatan Pandak; dan Barat : Sungai Progo. 1 Wilayah Kecamatan Pajangan berada di daerah dataran rendah. Ibukota Kecamatan Pajangan berada di ketinggian 100 meter diatas permukaan laut. Lokasi Kecamatan Pajangan yang berada di dataran rendah di daerah tropis memberikan iklim yang tergolong panas. Suhu tertinggi yang pernah tercatat di Kecamatan Pajangan adalah 32ºC dan suhu terendah 23ºC. -

Mayettes Shrimps Original and Authentic Philippines Cuisine Halabos $9.95 (Steamed) and Seasoned for Perfection

Seafood Specialties Mayettes Shrimps Original and Authentic Philippines Cuisine Halabos $9.95 (Steamed) and seasoned for perfection. Inihaw (Grilled) $9.95 Served on a bed of lettuce. Inihaw (Pan fried) $10.95 with garlic and green peppers. Tilapia Fish Inihaw (Grilled) $10.95 Served with rice and vegetables. Pinirito (Fried) $10.95 Served with rice and vegetables. Sarciado $10.95 Original Philippine Deserts Sautéed with garlic, ginger, onions and tomatoes combined with Leche Flan $5.95 scrambled eggs. Custard covered in caramel sauce Mussels (Seasonal) $10.95 Turon (Banana fritters) $5.95 Sautéed with garlic and ginger Served with topping of green onions With sweet coconut topping (3 pieces) Squid Mais Con Hielo $5.95 Mayettes Taste of the Philippines Sweet corn with shaved ice and evaporated milk Inihaw Grilled BBQ Style. $11.95 Cooking a Unique and Delightful Fusion of Cassava Cake $4.95 Adobo style $11.95 From the family of yams Spanish and Asian Cuisine. Sautéed with garlic, spices, onions, tomatoes. Halo Halo (mix–mix) $5.95 (416) 463–0338 Calamari $11.95 Internationally famous Philippines dessert Very refreshing dessert Breaded and deep fried. of a variety of exotic fruits,shaved ice, ice cream, yam and milk Take–Out and Dine In Bangus (Milk fish) Gulaman at Sago $4.95 Inihaw (Grilled medium size) $12.95 Tapioca and jelly topped with shaved ice and brown sugar Daing Bangus $12.95 Hours Milk fish filleted, marinated in vinegar and spices, deep fried Monday – Closed served with rice and vegetables. Tuesday to Saturday 11am–8pm Salmon Steak Catering Take–Out Sunday 11–5pm Inihaw (BBQ Style) $13.95 Ask about our extended hours for special occasions/ events Served with rice and vegetables. -

Analisis Strategi Pemasaran Pada Restoran Bakmi Japos Cabang Bogor

ANALISIS STRATEGI PEMASARAN PADA RESTORAN BAKMI JAPOS CABANG BOGOR SKRIPSI MARLIA PRATIWI PROGRAM STUDI SOSIAL EKONOMI PETERNAKAN FAKULTAS PETERNAKAN INSTITUT PERTANIAN BOGOR 2008 RINGKASAN MARLIA PRATIWI. D34104056. 2008. Analisis Strategi Pemasaran pada Restoran Bakmi Japos Cabang Bogor. Skripsi. Program Studi Sosial Ekonomi Peternakan, Fakultas Peternakan, Institut Pertanian Bogor. Pembimbing Utama : Ir. Asi H. Napitupulu, MSc. Pembimbing Anggota : Ir. Juniar Atmakusuma, MS Pergeseran pola konsumsi dan gaya hidup masyarakat perkotaan, terjadi peningkatan mobilitas fisik yang disebabkan oleh peningkatan aktivitas yang dilakukan di luar rumah. Kondisi ini membuat adanya peningkatan pada permintaan masyarakat terhadap makanan jadi. Jenis usaha yang terkait dengan penyediaan makanan adalah salah satunya melalui bisnis restoran. Bakmi Japos merupakan salah satu restoran yang muncul untuk memanfaatkan peluang pasar tersebut. Bakmi Japos telah memberikan alternatif sajian makanan yang sesuai dengan lidah masyarakat Indonesia serta turut memacu pertumbuhan restoran di Indonesia, khususnya di Kota Bogor. Tingkat persaingan diantara para pelaku usaha restoran semakin kompetitif. Persaingan tersebut menuntut Restoran Bakmi Japos Cabang Bogor perlu melakukan penyesuaian yang cepat dan terencana, sehingga diperlukan suatu perumusan strategi pemasaran yang tepat untuk menghadapi persaingan dengan restoran yang lain. Penelitian ini bertujuan 1) mengetahui bauran pemasaran jasa dan penilaian konsumen terhadap bauran pemasaran jasa yang selama ini diterapkan oleh Restoran Bakmi Japos Cabang Bogor, 2) mengetahui faktor-faktor dari lingkungan internal dan eksternal yang berpengaruh terhadap strategi pemasaran, dan 3) mengetahui alternatif strategi pemasaran yang tepat untuk Restoran Bakmi Japos Cabang Bogor agar dapat bersaing dengan para pesaingnya. Penelitian dilaksanakan selama satu bulan pada bulan 6 November s/d 6 Desember 2007 di Restoran Bakmi Japos Cabang Bogor, Jalan Otto Iskandardinata No. -

Pergub DIY No. 25 Tahun 2017 Ttg Standardisasi Makanan

SALINAN GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA PERATURAN GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA NOMOR 25 TAHUN 2017 TENTANG STANDARDISASI MAKANAN JAJANAN ANAK SEKOLAH DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA GUBERNUR DAERAH ISTIMEWA YOGYAKARTA, Menimbang : a. bahwa anak sebagai penerus cita-cita perjuangan bangsa, perlu mendapat kesempatan yang seluas-luasnya untuk tumbuh dan berkembang secara optimal, baik fisik, mental maupun sosial; b. bahwa untuk mendukung tumbuh kembang anak secara optimal perlu asupan makanan yang aman, sehat, bergizi dan layak dikonsumsi di lingkungan tumbuh kembangnya; c. bahwa masih ditemukan makanan jajanan anak sekolah yang tercemar bahan berbahaya baik fisik, kimia maupun kandungan mikrobiologi melebihi batas serta bakteri patogen; d. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a, huruf b, huruf c, dan huruf e perlu menetapkan Peraturan Gubernur tentang Standardisasi Jajanan Makanan Anak Sekolah; Mengingat : 1. Pasal 18 ayat (6) Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945; 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 3 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah Istimewa Jogjakarta (Berita Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1950 Nomor 3) sebagaimana telah diubah terakhir dengan Undang-Undang Nomor 9 Tahun 1955 tentang Perubahan Undang-undang Nomor 3 Jo. Nomor 19 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah Istimewa Jogjakarta (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1955 Nomor 43, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 827); 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 8 Tahun 1999 tentang Perlindungan Konsumen (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1999 Nomor 42, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3821); 4. Undang-Undang Nomor 36 Tahun 2009 tentang Kesehatan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2009 Nomor 144, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5063); 5. Undang-Undang Nomor 13 Tahun 2012 tentang Keistimewaan Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2012 Nomor 170, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5339); 6. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 259 3rd International Seminar on Tourism (ISOT 2018) The Reinforcement of Women's Role in Baluwarti as Part of Gastronomic Tourism and Cultural Heritage Preservation Erna Sadiarti Budiningtyas Dewi Turgarini Department English Language Catering Industry Management St. Pignatelli English Language Academy Indonesia University of Education Surakarta, Indonesia Bandung, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Surakarta has the potential of gastronomic I. INTRODUCTION heritage tourism. The diversity of cuisine becomes the power of Cultural heritage is one of the attractions that is able to Surakarta as a tourist attraction. Municipality of Surakarta stated that their Long Term Development Plan for 2005-2025 will bring tourists. One of the cultural heritage is gastronomic develop cultural heritage tourism and traditional values, tourism, which is related to traditional or local food and historical tourism, shopping and culinary tourism that is part of beverage. Gastronomic tourism is interesting because tourists gastronomic tourism. The study was conducted with the aim to do not only enjoy the traditional or local food and beverage, identifying traditional food in Baluwarti along with its historical, but are expected to get deeper value. They can learn about the tradition, and philosophical values. This area is selected because history and philosophy of the food and beverage that is eaten it is located inside the walls of the second fortress. Other than and drink, the making process, the ingredients, and how to that, it is the closest area to the center of Kasunanan Palace. The process it. If tourism is seen as a threat to the preservation of participation of Baluwarti women in the activity of processing cultural heritage, gastronomic tourism shows that tourism is traditional food has become the part of gastronomic tourism and not a threat to conservation, but can preserve the food and cultural heritage preservation. -

Crisostomo-Main Menu.Pdf

APPETIZERS Protacio’s Pride 345 Baked New Zealand mussels with garlic and cheese Bagumbayan Lechon 295 Lechon kawali chips with liver sauce and spicy vinegar dip Kinilaw ni Custodio 295 Kinilaw na tuna with gata HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Tinapa ni Tiburcio 200 310 Smoked milkfish with salted egg Caracol Ginataang kuhol with kangkong wrapped in crispy lumpia wrapper Tarsilo Squid al Jillo 310 Sautéed baby squid in olive oil with chili and garlic HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Calamares ni Tales 325 Fried baby squid with garlic mayo dip and sweet chili sauce Mang Pablo 385 Crispy beef tapa Paulita 175 Mangga at singkamas with bagoong Macaraig 255 Bituka ng manok AVAILABLE IN CLASSIC OR SPICY Bolas de Fuego 255 Deep-fried fish and squid balls with garlic vinegar, sweet chili, and fish ball sauce HOUSE SPECIAL KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Lourdes 275 Deep-fried baby crabs SEASONAL Sinuglaw Tarsilo 335 Kinilaw na tuna with grilled liempo Lucas 375 Chicharon bulaklak at balat ng baboy SIZZLING Joaquin 625 Tender beef bulalo with mushroom gravy Sisig Linares 250 Classic sizzling pork sisig WITH EGG 285 Victoria 450 Setas Salpicao 225 Sizzling salmon belly with sampalok sauce Sizzling button mushroom sautéed in garlic and olive oil KIDS LOVE IT! ALL PRICES ARE 12% VAT INCLUSIVE AND SUBJECTIVE TO 10% SERVICE CHARGE Carriedo 385 Sautéed shrimp gambas cooked -

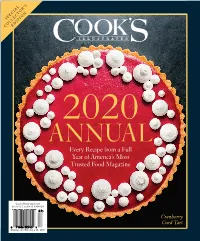

2020 Annual Recipe SIP.Pdf

SPECIAL COLLECTOR’SEDITION 2020 ANNUAL Every Recipe from a Full Year of America’s Most Trusted Food Magazine CooksIllustrated.com $12.95 U.S. & $14.95 CANADA Cranberry Curd Tart Display until February 22, 2021 2020 ANNUAL 2 Chicken Schnitzel 38 A Smarter Way to Pan-Sear 74 Why and How to Grill Stone 4 Malaysian Chicken Satay Shrimp Fruit 6 All-Purpose Grilled Chicken 40 Fried Calamari 76 Consider Celery Root Breasts 42 How to Make Chana Masala 77 Roasted Carrots, No Oven 7 Poulet au Vinaigre 44 Farro and Broccoli Rabe Required 8 In Defense of Turkey Gratin 78 Braised Red Cabbage Burgers 45 Chinese Stir-Fried Tomatoes 79 Spanish Migas 10 The Best Turkey You’ll and Eggs 80 How to Make Crumpets Ever Eat 46 Everyday Lentil Dal 82 A Fresh Look at Crepes 13 Mastering Beef Wellington 48 Cast Iron Pan Pizza 84 Yeasted Doughnuts 16 The Easiest, Cleanest Way 50 The Silkiest Risotto 87 Lahmajun to Sear Steak 52 Congee 90 Getting Started with 18 Smashed Burgers 54 Coconut Rice Two Ways Sourdough Starter 20 A Case for Grilled Short Ribs 56 Occasion-Worthy Rice 92 Oatmeal Dinner Rolls 22 The Science of Stir-Frying 58 Angel Hair Done Right 94 Homemade Mayo That in a Wok 59 The Fastest Fresh Tomato Keeps 24 Sizzling Vietnamese Crepes Sauce 96 Brewing the Best Iced Tea 26 The Original Vindaloo 60 Dan Dan Mian 98 Our Favorite Holiday 28 Fixing Glazed Pork Chops 62 No-Fear Artichokes Cookies 30 Lion’s Head Meatballs 64 Hummus, Elevated 101 Pouding Chômeur 32 Moroccan Fish Tagine 66 Real Greek Salad 102 Next-Level Yellow Sheet Cake 34 Broiled Spice-Rubbed 68 Salade Lyonnaise Snapper 104 French Almond–Browned 70 Showstopper Melon Salads 35 Why You Should Butter- Butter Cakes 72 Celebrate Spring with Pea Baste Fish 106 Buttermilk Panna Cotta Salad 36 The World’s Greatest Tuna 108 The Queen of Tarts 73 Don’t Forget Broccoli Sandwich 110 DIY Recipes America’s Test Kitchen has been teaching home cooks how to be successful in the kitchen since 1993. -

Aspek Dosimetri Makanan Olahan Tradisional Pada Fasilitas Irpasena

RisaJah Seminar lfmiah Penelitian daD Pengembangan Aplikasi lsotop daD Radias~ 2004 ASPEK DOSIMETRI MAKANAN OLAHAN TRADISIONAL PADA FASILITAS IRPASENA ABSTRAK ASPEK DOSIMETRI MAKANAN OLAHAN TRADISIONAL PADA FASILITAS IRP ASENA. Telah dilakukan penelitian aspek dosimetri terhadap makanan olahan tradisional yang diiradiasi di fasilitas irpasena. Sampel dike mas ke dalam 3 kotak ukuran standar yaitu kotak I (IS x 20 x 40) cm3, kotak II (25 x 20 x 40) cm3, clan kotak III (40 x 20 x 40) cm3lalu diiradiasi dengan kisaran dosis 3 kGy, clan hanya kotak III yang diiradiasi 5 kGy. Pengamatan yang dilakukan meliputi distribusi dosis, variasi ukuran kotak, clan monitoring dosimeter alanin. Distribusi dosis sampel dengan rapat massa tertentu, diukur dengan sistem dosimeter alanin clan dosimeter Fricke digunakan sebagai acuan. Hasil yang diperoleh menunjukkan bahwa pada dosis 3 kGy keseragaman distribusi dosis yang dinyatakan dalam perbandingan dosis maksimal (Dmaks) clan dosis minimal (Dmin) untuk sampel dengan rapat massa 0,89 g/cm3, masing-masing didapatkan kotak I -1,2413; kotak II -1,1630 clan kotak III -0,9830; sedang pada dosis 5 kGy kotak III diperoleh 0,8966. ABSTRACT ETHNIC FOOD DOSIMETRY ASPECT ON IRPASENA FACILITY. An experiment on ethnic food dosimetry aspect has been conducted using irpasena facility. The sample were packed in three standard variable boxes, namely box I (15 x 20 x 40) cm3, box II (25 x 20 x 40) cm3, and box III (40 x 20 x 40) cm3. They were irradiated with the doses of around 3 kGy and box III was irradiated with the dose of 5 kGy. Obesrvation of the experiment covers the distribution of dose, box side variable, and alanin dosemeter monitoring.