Attack on Lou Nuer Pastrolists, Akobo, April 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map Kebkabiya El Fashir Abyad Bara Umm Dam El Kawa Ermil Nahl Doka Umm Bel Sennar Tawila Dirra Umm El Hilla Iyal Es Suki El Hawata Keddada Mahbub El Obeid Rabak Jebel Shangil Tobay Wad Banda Dud Singa Gallabat Wada`ah Umm Rawaba En Nahud El Rahad Higar Galegu El Jebelein Kas Taweisha S U D A N El Abbasiya Nyala Dilling Kortala Dangur El Odaiya Geigar Sharafa Delami Ed Damazin Rashad Renk e l El Barun Ed Da`ein i El Lagowa Abu Jibaiha Edd El Fursan N Babanusa e Heiban t Abu Abu i Bau Guba Ragag h Matariq Kulshabi Bikori Gabra W El Muglad Kadugli Kologi Keili Mumallah Umm Ulu Buram Keilak Talodi Barbit Wadega Belfodiyo Qardud Kaka Paloich Tungaru Junguls Asosa Radom Riangnom Sumeih El Melemm Oriny Kodok Mendi Boing Bambesi Hofrat Naam Fagwir Aboke en Nahas Malakal Nejo Abyei UPPER NILE Daga Bentiu Gimbi Bai War-awar Fangak Malwal Post Kafia Pan Nyal Mayom Kingi Malualkon Abwong Wang Kai Fagwir Kan Sobat Banyjiel Gidami Sadi Aweil Wun Rog Yubdo Gossinga UNITY Gumbiel Nasser NORTHERN Gogrial Nyerol Malek Thul Raga BAHR Akop Leer Mogogh Biel Bure Metu Wun Gambela EL GHAZAL WARRAP Ayod Waat Abay Gore Kwajok Shwai Adok Atiedo Warrap Fathai Faddoi Jonglei Canal Tor Deim Zubeir Madeir E T H I O P I A Bisellia Bir Di Duk Fadiat Akobo WESTERN Wau Gech`a Lol Mbili Duk Kongettit Les Trois BAHR Wakela Atum Faiwil Tepi Riviêres EL GHAZAL Tonj Shambe Peper Pochalla LAKES Kongor C E N T R A L Bo River Post Rafili Giamciar Teferi Rumbek Lau Akelo Palwal Jonglei JONGLEI Pibor A F R I C A N Ubori Akot Pibor Yirol Kantiere R E P U -

The 8Th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan

The 8th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan Vaccines Work. Do Your Part! Submitted by the CORE Group Polio Project, South Sudan July 2018 INTRODUCTION This report documents efforts of South Sudan’s CORE Group Polio Project (CGPP) during the 8th African Vaccination Week (AVW) held in late April 2018. USAID provides funding for the CGPP’s immunization activities in 11 select counties in South Sudan. The brief highlights the implementation of program activities during AVW for the underserved, marginalized and hard-to-reach populations in Akobo County. From April 23 to April 29, CORE Group South Sudan collaborated with the Universal Network for Knowledge & Empowerment Agency (UNKEA), WHO, UNICEF, Nile Hope, International Medical Corps, and the Akobo County Health Department (CHD) that represents the Republic of South Sudan’s Ministry of Health. The main goal of the annual initiative is to strengthen immunization programs in South Sudan and to draw attention to the right of every child and woman to be protected from vaccine-preventable diseases. The theme for this year’s AVW was “Vaccines work. Do your part!” During the 2018 AVW, CORE Group undertook a variety of activities aimed at raising awareness through advocacy and social mobilization activities to promote the valuable benefits of immunization. These efforts resulted in increased numbers of children and women vaccinated through routine immunization outreach activities in Akobo County. SELECTING AKOBO COUNTY FOR AVW Akobo County is located in northeast South Sudan in Jonglei State and is situated near the international border of the Gambella Region of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

Humanitarian Response Plan South Sudan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

South Sudan Crisis Fact Sheet #44 May 30, 2014

SOUTH SUDAN – CRISIS FACT SHEET #44, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2014 MAY 30, 2014 1 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA F U N D I N G HIGHLIGHTS BY SECTOR IN FY 2014 A GLANCE Nearly 900 cholera cases, including 27 deaths, 2% reported in Juba since late April. 3% 5% New UNMISS mandate makes civilian 1,0 40,706 5% 24% protection a priority. Total Number of Individuals Four donors commit 86 percent of the new Displaced in South Sudan 12% since December 15 $618 million in pledges announced at the U.N. Office for the Coordination of humanitarian conference in Oslo, Norway. Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – May HUMANITARIAN FUNDING 30, 2014 12% 23% TO SOUTH SUDAN TO DATE IN FY 2014 95,000 14% USAID/OFDA $110,000,000 USAID/FFP2 $147,400,000 Total Number of Individuals Water, Sanitation, & Hygiene (24%) 3 Seeking Refuge at U.N. USAID/AFR $14,200,000 Logistics & Relief Supplies (23%) Mission in the Republic of Multi-Sector Rapid Response Fund (14%) 4 State/PRM $73,300,000 South Sudan (UNMISS) Agriculture & Food Security (12%) Compounds Health (12%) $344,900,000 Protection (5%) OCHA – May 30, 2014 Nutrition (5%) TOTAL USAID AND STATE Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (3%) HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE Economic Recovery and Market Systems (2%) TO SOUTH SUDAN 9 45,706 Total Number of Individuals Displaced in Other Areas of KEY DEVELOPMENTS South Sudan The number of cholera cases in South Sudan continues to steadily increase, with nearly 900 OCHA – May 30, 2014 cases, including 27 cholera-related deaths, reported in Juba, Central Equatoria State, since late April, according to the U.N. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Social Assessment Report for Provision of Essential Health Services Project (PEHSP) Public Disclosure Authorized UNICEF South Sudan Public Disclosure Authorized 25 September 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 This is a working document. It has been prepared to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and as part of a submission to the World Bank Group. The text has not been edited to official publication standards and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this publication do not imply an opinion on legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. 2 Table of Contents LIST OF ABREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................................5 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................7 1.1 Project rationale ............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 The PEHSP objectives .................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Security risks and mitigation measures ............................................................................................... -

Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Security responses in Jonglei State in the aftermath of inter-ethnic violence By Richard B. Rands and Dr. Matthew LeRiche Saferworld February 2012 1 Contents List of acronyms 1. Introduction and key findings 2. The current situation: inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei 3. Security responses 4. Providing an effective response: the challenges facing the security forces in South Sudan 5. Support from UNMISS and other significant international actors 6. Conclusion List of Acronyms CID Criminal Intelligence Division CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CRPB Conflict Reduction and Peace Building GHQ General Headquarters GoRSS Government of the Republic of South Sudan ICG International Crisis Group MSF Medecins Sans Frontières MI Military Intelligence NISS National Intelligence and Security Service NSS National Security Service SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary General SSP South Sudanese Pounds SSPS South Sudan Police Service SSR Security Sector Reform UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UYMPDA Upper Nile Youth Mobilization for Peace and Development Agency Acknowledgements This paper was written by Richard B. Rands and Dr Matthew LeRiche. The authors would like to thank Jessica Hayes for her invaluable contribution as research assistant to this paper. The paper was reviewed and edited by Sara Skinner and Hesta Groenewald (Saferworld). Opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of Saferworld. Saferworld is grateful for the funding provided to its South Sudan programme by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) through its South Sudan Peace Fund and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) through its Global Peace and Security Fund. -

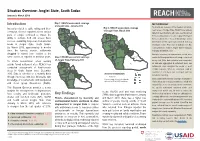

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

49A65b110.Pdf

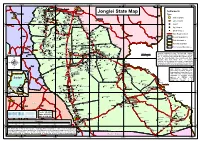

30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E Buheyrat No ") Popuoch Maya Sinyora Wath Wang Kech Malakal Dugang New Fangak Juaibor " Fatwuk " Pul Luthni Doleib Hill Fakur Ful Nyak " Settlements Rub-koni Ngwer Gar Keuern Fachop " Mudi Kwenek Konna Jonglei State Map Yoynyang Kau Keew Tidfolk " Fatach Fagh Atar Nyiyar Wunalong Wunakir Type Jwol Dajo ") Tiltil Torniok Atar 2 Machar Shol Ajok Fangak Kir Nyin Yar Kuo " Nur Yom Chotbora AbwongTarom ") State Capitals Bentiu Chuth Akol Fachod Thantok Kuleny Abon Abwong Jat Paguir Abuong Ayiot Ariath OLD FANGAK Fangak " ") Kot Fwor Lam Baar Shwai Larger Towns Fulfam Fajur Malualakon Tor Lil Riep ") Madhol ATAR N Rier Mulgak N " " " Mayen Pajok Foan Wuriyang Kan 0 0 ' " ' Kaljak Dier Wunlam Upper Nile Towns 0 Gon Toych Wargar 0 ° Akuem Toch Wunrok Kuey ° 9 Long Wundong Ayien Gwung Tur Dhiak Kuei 9 Fulkwoz Weibuini Dornor Tam Kolatong Wadpir Wunapith Nyinabot Big Villages Fankir Yarkwaich Chuai Twengdeng Mawyek Muk Tidbil Fawal Wunador Manyang Gadul Nyadin Wunarual Tel Luwangni Small Villages Rublik List Wunanomdamir Piath Nyongchar Yafgar Paguil Kunmir Toriak Akai Uleng Fanawak Pagil Fawagik Kor Nyerol Nyirol Main Road Network Nyakang Liet Tundi Wuncum Tok Rial Kurnyith Gweir Lung Nasser Koch Nyod Falagh Kandak Pulturuk Maiwut " Famyr Tar Turuk ") County Boundaries Jumbel Menime Kandag Dor " Dur NYIROL Ad Fakwan Haat Agaigai Rum Kwei Ket Thol Wor Man Lankien State Boundaries Dengdur Maya Tawil Raad Turu Garjok Mojogh Obel Pa Ing Wang Gai Rufniel Mogok Maadin Nyakoi Futh Dengain Mandeng Kull -

South Sudan 2021 Humanitarian Response Plan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

Review of Rinderpest Control in Southern Sudan 1989-2000

Review of Rinderpest Control in Southern Sudan 1989-2000 Prepared for the Community-based Animal Health and Epidemiology (CAPE) Unit of the Pan African Programme for the Control of Epizootics (PACE) Bryony Jones March 2001 Acknowledgements The information contained in this document has been collected over the years by southern Sudanese animal health workers, UNICEF/OLS Livestock Project staff, Tufts University consultants, and the staff of NGOs that have supported community-based animal health projects in southern Sudan (ACROSS, ACORD, ADRA, DOT, GAA, NPA, Oxfam-GB, Oxfam-Quebec, SC-UK, VETAID, VSF-B, VSF-CH, VSF-G, Vetwork Services Trust, World Relief). The individuals involved are too numerous to name, but their hard work and contribution of information is gratefully acknowledged. The data from the early years of the OLS Livestock Programme (1993 to 1996) was collated by Tim Leyland, formerly UNICEF/OLS Livestock Project Officer. Disease outbreak information from 1998 to date has been collated by Dr Gachengo Matindi, FAO/OLS Livestock Officer (formerly UNICEF/OLS Livestock Officer). Rinderpest serology and virus testing has mainly been carried out by National Veterinary Research Centre, Muguga, Nairobi. Any errors or omissions in this review are the fault of the author. If any reader has additional information to correct an error or omission the author would be grateful to receive this information. For further information contact: CAPE Unit PACE Programme OAU/IBAR PO Box 30786 Nairobi Tel: Nairobi 226447 Fax: Nairobi 226565 E mail: [email protected] Or the author: Bryony Jones PO Box 13434 Nairobi Kenya Tel: Nairobi 580799 E mail: [email protected] 2 CONTENTS Page 1. -

An Analysis of Uror and Nyirol Counties, South Sudan

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Livelihoods, access to services and perceptions of governance: An analysis of Uror and Nyirol counties, South Sudan Report 3 Daniel Maxwell, Martina Santschi, Rachel Gordon, Philip Dau and Leben Moro April 2014 Written by Daniel Maxwell (Tufts University, Team Leader), Martina Santschi (swisspeace), Rachel Gordon (Tufts University), Philip Dau (National Bureau of Statistics and Leben Moro (University of Juba). SLRC reports present information, analysis and key policy recommendations on issues relating to livelihoods, basic services and social protection in conflict affected situations. This and other SLRC reports are available from www.securelivelihoods.org. Funded by DFID, Irish Aid and EC. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of SLRC, DFID, Irish Aid and EC. ©SLRC 2014. Readers are encouraged to quote or reproduce material from SLRC for their own publications. As copyright holder SLRC, requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium Overseas Development Institute (ODI) 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 7922 8249 F +44 (0)20 7922 0399 E [email protected] www.securelivelihoods.org About us The Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) is a six-year project funded by DFID, Irish Aid and EC. SLRC aims to bridge the gaps in knowledge about: ■ When it is appropriate to build secure livelihoods in conflict-affected situations (CAS) in addition to meeting immediate acute needs; ■ What building blocks (e.g. humanitarian assistance, social protection, agriculture and basic services) are required in different contexts; ■ Who can best deliver building blocks to secure livelihoods in different contexts; and ■ How key investments can be better and more predictably supported by effective financing mechanisms.