Identification of ANKRD11 and ZNF778 As Candidate Genes For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architecture of a Lymphomyeloid Developmental Switch Controlled by PU.1, Notch and Gata3 Marissa Morales Del Real and Ellen V

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Caltech Authors DEVELOPMENT AND STEM CELLS RESEARCH ARTICLE 1207 Development 140, 1207-1219 (2013) doi:10.1242/dev.088559 © 2013. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd Architecture of a lymphomyeloid developmental switch controlled by PU.1, Notch and Gata3 Marissa Morales Del Real and Ellen V. Rothenberg* SUMMARY Hematopoiesis is a classic system with which to study developmental potentials and to investigate gene regulatory networks that control choices among alternate lineages. T-cell progenitors seeding the thymus retain several lineage potentials. The transcription factor PU.1 is involved in the decision to become a T cell or a myeloid cell, and the developmental outcome of expressing PU.1 is dependent on exposure to Notch signaling. PU.1-expressing T-cell progenitors without Notch signaling often adopt a myeloid program, whereas those exposed to Notch signals remain in a T-lineage pathway. Here, we show that Notch signaling does not alter PU.1 transcriptional activity by degradation/alteration of PU.1 protein. Instead, Notch signaling protects against the downregulation of T-cell factors so that a T-cell transcriptional network is maintained. Using an early T-cell line, we describe two branches of this network. The first involves inhibition of E-proteins by PU.1 and the resulting inhibition of Notch signaling target genes. Effects of E- protein inhibition can be reversed by exposure to Notch signaling. The second network is dependent on the ability of PU.1 to inhibit important T-cell transcription factor genes such as Myb, Tcf7 and Gata3 in the absence of Notch signaling. -

Supplemental Table S1

Entrez Gene Symbol Gene Name Affymetrix EST Glomchip SAGE Stanford Literature HPA confirmed Gene ID Profiling profiling Profiling Profiling array profiling confirmed 1 2 A2M alpha-2-macroglobulin 0 0 0 1 0 2 10347 ABCA7 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 7 1 0 0 0 0 3 10350 ABCA9 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 9 1 0 0 0 0 4 10057 ABCC5 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 5 1 0 0 0 0 5 10060 ABCC9 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 9 1 0 0 0 0 6 79575 ABHD8 abhydrolase domain containing 8 1 0 0 0 0 7 51225 ABI3 ABI gene family, member 3 1 0 1 0 0 8 29 ABR active BCR-related gene 1 0 0 0 0 9 25841 ABTB2 ankyrin repeat and BTB (POZ) domain containing 2 1 0 1 0 0 10 30 ACAA1 acetyl-Coenzyme A acyltransferase 1 (peroxisomal 3-oxoacyl-Coenzyme A thiol 0 1 0 0 0 11 43 ACHE acetylcholinesterase (Yt blood group) 1 0 0 0 0 12 58 ACTA1 actin, alpha 1, skeletal muscle 0 1 0 0 0 13 60 ACTB actin, beta 01000 1 14 71 ACTG1 actin, gamma 1 0 1 0 0 0 15 81 ACTN4 actinin, alpha 4 0 0 1 1 1 10700177 16 10096 ACTR3 ARP3 actin-related protein 3 homolog (yeast) 0 1 0 0 0 17 94 ACVRL1 activin A receptor type II-like 1 1 0 1 0 0 18 8038 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 1 0 0 0 0 19 8751 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 1 0 0 0 0 20 8728 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 1 0 0 0 0 21 81792 ADAMTS12 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 12 1 0 0 0 0 22 9507 ADAMTS4 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 -

Supplementary Figure 1. Qrt-PCR Analyses for Measuring the Knockdown Efficiency of Transcription Factors. A549 and U937 Cells Kn

Supplementary Figure 1. qRT-PCR analyses for measuring the knockdown efficiency of transcription factors. A549 and U937 cells knocking down or overexpressing different transcription factors including NF-κB subunits p65 and p50 (A), HIF1 (B), TCF4 (C), AP-1 subunits c-Jun and c-FOS (D), or FOXP3 (E) were subjected to RNA isolation, followed by qRT-PCR analyses to examine the expression of these transcription factors. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. 1 Supplementary Figure 2. Effects of FOXP3 downregulation and overexpression on the expression of NLRP1, IL1B and IL18. A549 and U937 cells were transfected with si-FOXP3 or pCDNA3-2×Flag-FOXP3. After 24 h, cells were subjected to RNA isolation, followed by qRT-PCR analyses to examine the expression of NLRP1 (A), IL1B (B) and IL18 (C). ***P<0.001. 2 Supplementary Figure 3. Effects of CtBP2 downregulation and overexpression on the expression of miR-199a-3p, NLRP1, IL1B and IL18. A549 and U937 cells were transfected with si-CtBP2 or pCDNA3-2×Flag-CtBP2. After 24 h, cells were subjected to RNA isolation, followed by qRT-PCR analyses to examine the expression of miR-199a-3p (A), NLRP1 (B), IL1B (C) and IL18 (D). ***P<0.001. 3 Supplementary Figure 4. CHFTC specifically bond to the promoter of miR-199a-3p. (A and B) Effects of CtBP2 knockdown and overexpression on HDAC1 and FOXP3 protein levels. A549 cells were transfected with two CtBP2-specific shRNAs and pCDNA3-2×Flag-CtBP2 to obtain two CtBP2-knockdown cell lines (KD-1 and KD-2) (A) and two CtBP2-overexpression cells lines (OE-1 and OE-2) (B), respectively. -

ANKRD11 Gene Ankyrin Repeat Domain 11

ANKRD11 gene ankyrin repeat domain 11 Normal Function The ANKRD11 gene provides instructions for making a protein called ankyrin repeat domain 11 (ANKRD11). As its name suggests, this protein contains multiple regions called ankyrin domains; proteins with these domains help other proteins interact with each other. The ANKRD11 protein interacts with certain proteins called histone deacetylases, which are important for controlling gene activity. Through these interactions, ANKRD11 affects when genes are turned on and off. For example, ANKRD11 brings together histone deacetylases and other proteins called p160 coactivators. This association regulates the ability of p160 coactivators to turn on gene activity. ANKRD11 may also enhance the activity of a protein called p53, which controls the growth and division (proliferation) and the self-destruction (apoptosis) of cells. The ANKRD11 protein is found in nerve cells (neurons) in the brain. During embryonic development, ANKRD11 helps regulate the proliferation of these cells and development of the brain. Researchers speculate that the protein may also be involved in the ability of neurons to change and adapt over time (plasticity), which is important for learning and memory. ANKRD11 may function in other cells in the body and appears to be involved in normal bone development. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes KBG syndrome Several ANKRD11 gene mutations have been found to cause KBG syndrome, a condition characterized by large upper front teeth and other unusual facial features, skeletal abnormalities, and intellectual disability. Most of these mutations lead to an abnormally short ANKRD11 protein, which likely has little or no function. Reduction of this protein's function is thought to underlie the signs and symptoms of the condition. -

Supp Table 1.Pdf

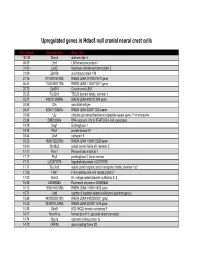

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

Rabbit Anti-ANKRD11/FITC Conjugated Antibody-SL16651R

SunLong Biotech Co.,LTD Tel: 0086-571- 56623320 Fax:0086-571- 56623318 E-mail:[email protected] www.sunlongbiotech.com Rabbit Anti-ANKRD11/FITC Conjugated antibody SL16651R-FITC Product Name: Anti-ANKRD11/FITC Chinese Name: FITC标记的锚蛋白重复结构域蛋白11抗体 ANCO 1; ANCO1; Ankyrin repeat containing cofactor 1; Ankyrin repeat domain 11; Alias: Ankyrin repeat domain containing protein 11; LZ16; T13; ANR11_HUMAN; Ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 11; Ankyrin repeat-containing cofactor 1. Organism Species: Rabbit Clonality: Polyclonal React Species: ICC=1:50-200IF=1:50-200 Applications: not yet tested in other applications. optimal dilutions/concentrations should be determined by the end user. Molecular weight: 296kDa Form: Lyophilized or Liquid Concentration: 2mg/1ml immunogen: KLH conjugated synthetic peptide derived from human ANKRD11 Lsotype: IgG Purification: affinity purified by Protein A Storage Buffer: 0.01Mwww.sunlongbiotech.com TBS(pH7.4) with 1% BSA, 0.03% Proclin300 and 50% Glycerol. Store at -20 °C for one year. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. The lyophilized antibody is stable at room temperature for at least one month and for greater than a year Storage: when kept at -20°C. When reconstituted in sterile pH 7.4 0.01M PBS or diluent of antibody the antibody is stable for at least two weeks at 2-4 °C. background: Ankyrin is a membrane protein that mediates the attachment of the erythrocyte membrane skeleton to the plasma membrane and interacts with CD44 and inositol triphosphate. It contains three functional domains: a conserved N-terminal ankyrin Product Detail: repeat domain (ARD(consisting of 22–24 tandem repeats of 33 amino acids), a spectrin binding domain and a variably sized C-terminal regulatory domain. -

A Private 16Q24.2Q24.3 Microduplication in a Boy with Intellectual Disability, Speech Delay and Mild Dysmorphic Features

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article A Private 16q24.2q24.3 Microduplication in a Boy with Intellectual Disability, Speech Delay and Mild Dysmorphic Features Orazio Palumbo * , Pietro Palumbo , Ester Di Muro, Luigia Cinque, Antonio Petracca, Massimo Carella and Marco Castori Division of Medical Genetics, Fondazione IRCCS-Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo, 71013 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (E.D.M.); [email protected] (L.C.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-088-241-6350 Received: 5 June 2020; Accepted: 24 June 2020; Published: 26 June 2020 Abstract: No data on interstitial microduplications of the 16q24.2q24.3 chromosome region are available in the medical literature and remain extraordinarily rare in public databases. Here, we describe a boy with a de novo 16q24.2q24.3 microduplication at the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)-array analysis spanning ~2.2 Mb and encompassing 38 genes. The patient showed mild-to-moderate intellectual disability, speech delay and mild dysmorphic features. In DECIPHER, we found six individuals carrying a “pure” overlapping microduplication. Although available data are very limited, genomic and phenotype comparison of our and previously annotated patients suggested a potential clinical relevance for 16q24.2q24.3 microduplication with a variable and not (yet) recognizable phenotype predominantly affecting cognition. Comparing the cytogenomic data of available individuals allowed us to delineate the smallest region of overlap involving 14 genes. Accordingly, we propose ANKRD11, CDH15, and CTU2 as candidate genes for explaining the related neurodevelopmental manifestations shared by these patients. -

Table S1. Folds of Genes Expression Change in HUVEC After Treatment with 10Ug/Ml S100A8

Table S1. Folds of genes expression change in HUVEC after treatment with 10ug/mL S100A8 Probe a,b RefSeq Gene description fold-4hr fold-24hr A_23_P120883 NM_002133 heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 1.686 1.881 A_24_P418517 AL353580 nucleophosmin pseudogene 1.746 1.746 A_24_P59239 1.751 1.723 A_24_P170186 1.724 1.744 A_24_P178154 1.716 1.678 A_24_P58759 AC008628 similar to chaperonin containing Tcp1, subunit 1.651 1.670 5 (epsilon) A_24_P33429 AADB02001452 similar to nucleophosmin 1 1.635 1.680 A_24_P621434 1.605 1.709 A_24_P358337 1.687 1.595 A_24_P814872 1.635 1.598 A_24_P350160 NM_198262 arginine/serine-rich coiled-coil 2 1.690 1.543 A_24_P306921 AADB02017686 similar to ATP synthase, H+ transporting, 1.629 1.591 mitochondrial F0 complex, subunit B1 A_24_P332862 NM_175910 zinc finger protein 493 1.642 1.561 A_24_P202497 NM_020648 twisted gastrulation homolog 1 (Drosophila) 1.565 1.548 A_24_P209378 NM_016220 zinc finger protein 107 1.553 1.519 A_24_P281801 1.533 1.526 A_24_P32849 NM_001011725 heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein 1.764 A1-like 2 A_32_P165477 NM_014331 solute carrier family 7, (cationic amino acid 1.755 transporter, y+ system) member 11 A_32_P24376 NM_033184 keratin associated protein 2-1; keratin 1.742 associated protein 2-4; keratin associated protein 2-3; similar to keratin associated protein 2-4; keratin associated protein 2-2 A_32_P87013 NM_000584 interleukin 8 1.738 A_23_P253622 XM_001719592 similar to KIAA1641; similar to ankyrin repeat 1.725 domain 26; ankyrin repeat domain 36B A_23_P428287 NM_001080383 gap junction protein, gamma 1, 45kDa 1.724 A_24_P187094 1.723 A_24_P307075 AC097709 similar to heterogeneous nuclear 1.708 ribonucleoprotein A1 A_23_P142272 NM_019088 Paf1, RNA polymerase II associated factor, 1.706 homolog (S. -

Comprehensive Analysis of Clinical Spectrum and Genotype Associations in Chinese and Literature Reported KBG Syndrome

842 Original Article Comprehensive analysis of clinical spectrum and genotype associations in Chinese and literature reported KBG syndrome Qiuyue Li, Chengjun Sun, Lin Yang, Wei Lu, Feihong Luo^ Department of Pediatric Endocrinology and Inherited Metabolic Diseases, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: Q Li, C Sun, F Luo; (II) Administrative support: L Yang, F Luo; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: L Yang, W Lu; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Q Li, C Sun, L Yang; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Q Li, C Sun, W Lu; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Feihong Luo. Department of Endocrinology and Inherited Metabolic Diseases, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, 399 Wanyuan Road, Shanghai, China. Email: [email protected]. Background: Patients with KBG Syndrome due to ANKRD11 mutations and 16q24.3 microdeletions including ANKRD11 were identified. Classical and most frequent phenotypes include various degrees of intelligence disability (ID), short stature (SS), delayed bone age, macrodontia, distinctive facial features and skeletal anomalies. The variable expressivity of KBG syndrome makes it challenging to establish genotype- phenotype correlations, which also affects further studies for this novel syndrome. We aim to report three unrelated patients with KBG syndrome caused by ANKRD11 gene pathological variants and to evaluate potential associations among ANKRD11 gene variant types, the 16q24.3 microdeletion, and the clinical spectrum of KBG syndrome. Methods: The genetic etiology of three unreported KBG patients was identified by whole exome sequencing and confirmed via Sanger sequencing. Literature review was conducted to summarize the phenotype-genotype relationship based on three unreported Chinese cases and 186 reported cases. -

Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Copper Balance in Human Cells

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS REGULATING COPPER BALANCE IN HUMAN CELLS by Nesrin M. Hasan A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2014 ©2014 Nesrin M. Hasan All Rights Reserved Intended to be blank ii ABSTRACT Precise copper balance is essential for normal growth, differentiation, and function of human cells. Loss of copper homeostasis is associated with heart hypertrophy, liver failure, neuronal de-myelination and other pathologies. The copper-transporting ATPases ATP7A and ATP7B maintain cellular copper homeostasis. In response to copper elevation, they traffic from the trans-Golgi network (TGN) to vesicles where they sequester excess copper for further export. The mechanisms regulating activity and trafficking of ATP7A/7B are not well understood. Our studies focused on determining the role of kinase-mediated phosphorylation in copper induced trafficking of ATP7B, and identifying and characterizing novel regulators of ATP7A. We have shown that Ser- 340/341 region of ATP7B plays an important role in interactions between the N-terminus and the nucleotide-binding domain and that mutations in these residues result in vesicular localization of the protein independent of the intracellular copper levels. We have determined that structural changes that alter the inter-domain interactions initiate exit of ATP7B from the TGN and that the role of copper-induced kinase-mediated hyperphosphorylation might be to maintain an open interface between the domains of ATP7B. In a separate study, seven proteins were identified, which upon knockdown result in increased intracellular copper levels. We performed an initial characterization of the knock-downs and obtained intriguing results indicating that these proteins regulate ATP7A protein levels, post-translational modifications, and copper-dependent trafficking. -

Systematic Integration of GATA Transcription Factors and Epigenomes Via IDEAS Paints the Regulatory Landscape of Hematopoietic Cells

Received: 2 July 2019 Accepted: 17 October 2019 DOI: 10.1002/iub.2195 CRITICAL REVIEW Systematic integration of GATA transcription factors and epigenomes via IDEAS paints the regulatory landscape of hematopoietic cells Ross C. Hardison1 | Yu Zhang1 | Cheryl A. Keller1 | Guanjue Xiang1 | Elisabeth F. Heuston2 | Lin An1 | Jens Lichtenberg2 | Belinda M. Giardine1 | David Bodine2 | Shaun Mahony1 | Qunhua Li1 | Feng Yue3 | Mitchell J. Weiss4 | Gerd A. Blobel5 | James Taylor6 | Jim Hughes7 | Douglas R. Higgs7 | Berthold Göttgens8 1Departments of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and of Statistics, The Abstract Pennsylvania State University, University Members of the GATA family of transcription factors play key roles in the dif- Park, PA ferentiation of specific cell lineages by regulating the expression of target 2 Genetics and Molecular Biology Branch, genes. Three GATA factors play distinct roles in hematopoietic differentiation. Hematopoiesis Section, National Institutes of Health, NHGRI, Bethesda, MD In order to better understand how these GATA factors function to regulate 3Department of Biochemistry and genes throughout the genome, we are studying the epigenomic and transcrip- Molecular Biology, The Pennsylvania State tional landscapes of hematopoietic cells in a model-driven, integrative fashion. University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA We have formed the collaborative multi-lab VISION project to conduct ValI- 4Hematology Department, St. Jude dated Systematic IntegratiON of epigenomic data in mouse and human hema- Children's Research Hospital, topoiesis. The epigenomic data included nuclease accessibility in chromatin, Memphis, TN CTCF occupancy, and histone H3 modifications for 20 cell types covering 5Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, hematopoietic stem cells, multilineage progenitor cells, and mature cells across Philadelphia, PA 6Departments of Biology and of Computer the blood cell lineages of mouse. -

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

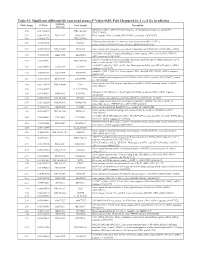

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds.