Student Press Exceptionalism Sonja R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brad's September Newsletter

Wagon Days and September Events September is here and August has come to an end, but this doesn’t mean that Sun Valley’s lineup of summer events is over! September brings the Big Hitch Parade, antique fairs and phenomenal performances throughout our Valley. Wagon Days starts off with the Cowboy Poets Recital at the Ore Wagon Museum on Sept. 2nd at 11:00 am and culminates with the iconic Big Hitch Parade at 1:00 pm on Sept. 3rd, the largest non- motorized parade in the west. See over one hundred museum quality wagons, stage coaches, buggies, carriages and the six enormous Lewis Ore Wagons, pulled by a 20 mule jerkline. Antique fairs will also abound throughout the Valley from Sept. 2nd - 5th, at these locations: Hailey’s Antique Market, at Roberta McKercher Park, Hailey Sept 1 - 4 all day Ketchum Antique and Art Show, nexStage Theater, 120 n Main Street, Sept 2 - 4 all day. The California-based rock group Lukas Nelson and the Promise of the Real will conclude Sun Valley’s 2016 summer concert series on Labor Day, Sept. 5th. The show will open at the Sun Valley Pavilion at 6:00pm, with tickets ranging from $25 for the lawn to $100 for pavilion seats. The Sun Valley Center for the Arts will begin its 2016-17 performing arts series starting September 16th with award winning cabaret performer, Sharron Matthews. Her performance spans a mix of storytelling and mash-up pop songs. Her 2010 “Sharron Matthews Superstar: World Domination Tour 2010” was named “#1 Cabaret in New York City’ by Nightlife Exchange and WPAT Radio, and she was also nominated Touring Artist of the Year by the BC touring council in 2015. -

College of Letters 1

College of Letters 1 Kari Weil BA, Cornell University; MA, Princeton University; PHD, Princeton University COLLEGE OF LETTERS University Professor of Letters; University Professor, Environmental Studies; The College of Letters (COL) is a three-year interdisciplinary major for the study University Professor, College of the Environment; University Professor, Feminist, of European literature, history, and philosophy, from antiquity to the present. Gender, and Sexuality Studies; Co-Coordinator, Animal Studies During these three years, students participate as a cohort in a series of five colloquia in which they read and discuss (in English) major literary, philosophical, and historical texts and concepts drawn from the three disciplinary fields, and AFFILIATED FACULTY also from monotheistic religious traditions. Majors are invited to think critically about texts in relation to their contexts and influences—both European and non- Ulrich Plass European—and in relation to the disciplines that shape and are shaped by those MA, University of Michigan; PHD, New York University texts. Majors also become proficient in a foreign language and study abroad Professor of German Studies; Professor, Letters to deepen their knowledge of another culture. As a unique college within the University, the COL has its own library and workspace where students can study together, attend talks, and meet informally with their professors, whose offices VISITING FACULTY surround the library. Ryan Fics BA, University of Manitoba; MA, University of Manitoba; PHD, Emory -

Culture War, Rhetorical Education, and Democratic Virtue Beth Jorgensen Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2002 Takin' it to the streets: culture war, rhetorical education, and democratic virtue Beth Jorgensen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Philosophy Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jorgensen, Beth, "Takin' it to the streets: culture war, rhetorical education, and democratic virtue " (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 969. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/969 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, white others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bieedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Werewere Liking, Sony Labou Tansi, and Tchicaya U Tam'si

WEREWERE LIKING, SONY LABOU TANSI, AND TCHICAYA U TAM’SI: PIONEERS OF “NEW THEATER” IN FRANCOPHONE AFRICA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Salome Wekisa Fouts, B.A., M.A ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor John-Conteh-Morgan, Adviser _________________________________ Professor Karlis Racevskis, Adviser _________________________________ Advisers Professor Jennifer Willging Department of French and Italian Copyright by Salome Wekisa Fouts 2004 ABSTRACT This dissertation is an analysis of “new African theater” as illustrated in the works of three francophone African writers: the late Congolese Sony Labou Tansi (formerly known as Marcel Ntsony), the late Congolese Félix Tchicaya, who wrote under the pseudonym Tchicaya U Tam’si, and the Cameroonian Werewere Liking. The dissertation examines plays by these authors and illustrates how the plays clearly stand apart from mainstream modern French-language African theater. The introduction, in Chapter 1 provides an explanation of the meaning that has been assigned to the term “new African theater.” It presents an overview of the various innovative structural and linguistic techniques new theater playwrights use that render their work avant-garde. The chapter also studies how new theater playwrights differ from mainstream ones, especially in the way they address and present their concerns regarding the themes of oppression, rebellion, and the outcome of rebellion. The information provided in this chapter serves as a springboard to the primary focus of the dissertation, which is a detailed theoretical and textual analysis of experimental strategies used by the three playwrights in the areas of theme, form, and language. -

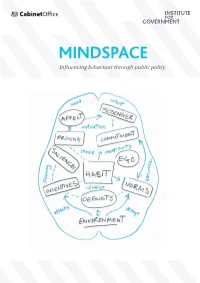

MINDSPACE: Influencing Behaviour Through Public

MINDSPACE Influencing behaviour through public policy 2 Discussion document – not a statement of government policy Contents Foreword 4 Executive Summary 7 Introduction: Understanding why we act as we do 11 MINDSPACE: A user‟s guide to what affects our behaviour 18 Examples of MINDSPACE in public policy 29 Safer communities 30 The good society 36 Healthy and prosperous lives 42 Applying MINDSPACE to policy-making 49 Public permission and personal responsibility 63 Conclusions and future challenges 73 Annexes 80-84 MINDSPACE diagram 80 New possible approaches to current policy problems 81 New frontiers of behaviour change: Insight from experts 83 References 85 Discussion document – not a statement of government policy 3 Foreword Influencing people‟s behaviour is nothing new to Government, which has often used tools such as legislation, regulation or taxation to achieve desired policy outcomes. But many of the biggest policy challenges we are now facing – such as the increase in people with chronic health conditions – will only be resolved if we are successful in persuading people to change their behaviour, their lifestyles or their existing habits. Fortunately, over the last decade, our understanding of influences on behaviour has increased significantly and this points the way to new approaches and new solutions. So whilst behavioural theory has already been deployed to good effect in some areas, it has much greater potential to help us. To realise that potential, we have to build our capacity and ensure that we have a sophisticated understanding of what does influence behaviour. This report is an important step in that direction because it shows how behavioural theory could help achieve better outcomes for citizens, either by complementing more established policy tools, or by suggesting more innovative interventions. -

Words, Words, Words 20 13

University of South Carolina Aiken Vo l u m e 12 , Words, Words, Words 20 13 The Annual English Department Polonius: What do you read, my lord? Newsletter Hamlet: Words, words, words. Act II, Scene II From The Chair For academic year 2013-14, USCA is launching a new strategic plan with the intent of moving the campus forward under the leadership of our new chancellor, Dr. Sandra Jordan. This is a good time for the Department to take stock of its current efforts and to plan ahead for the future. To that end, our faculty periodically reexamines the English curriculum to make sure that we are responding both to the needs of our students and the expectations of a rapidly changing socie- ty. This fall, for example, we revised our minor in professional writing to intro- duce a new gateway course, ENGL 245: Writing in the Workplace. We hope that this new offering will help USCA better meet the demand of employers for individuals who are conversant with typical workplace formats such as proce- dural writing and grant writing. Today’s corporate leaders consistently cite writing proficiency as one of the three skills they value most in their employ- ees. Just as the members of our faculty continually monitor the curricu- lum to keep the educational experience of our students engaging and relevant, the scholar-teachers that make up the Department of English challenge them- selves to reach new heights of productivity. After all, to demand scholarship of our students, we ourselves must be active scholars. This year alone, members of the English faculty completed or are in the process of completing seven book projects; they published over 30 shorter scholarly or creative works; they presented nearly 20 papers at professional conferences. -

English (ENGL) 1

English (ENGL) 1 ENGL130 The English Essay This course will focus on the writing of nonfiction and the forms of the English ENGLISH (ENGL) essay. Readings will be drawn from a range of genres, both nonfiction and fiction, ENGL113 A Nation of Immigrants? including memoirs and profiles, historical and contemporary commentary, short America is a nation of immigrants. This ideological epithet has come to define stories and novels. the American experience as one of opportunity, advancement, and national Offering: Host incorporation. This course will approach this narrative from the perspective of Grading: A-F im/migrants, refugees, exiles, displaced persons, and colonized minorities. To do Credits: 1.00 so, we will read sociology, history, and political theory alongside literary texts, Gen Ed Area: HA-ENGL inquiring into discourses of migration, mobility, and (un)belonging through an Prereq: None interdisciplinary and intersectional lens. ENGL131 Writing About Places Offering: Crosslisting This course is one in a series called "writing about places" exploring the long Grading: OPT tradition of writing about travel and places and changing attitudes toward Credits: 1.00 crossing cultural and geographical borders. Readings will focus largely on Gen Ed Area: HA-WRCT the writings of 20th-century travelers and will include an examination of the Identical With: WRCT113 phenomenon of migration. We will examine historical and cultural interactions/ Prereq: None confrontations as portrayed by both insiders and outsiders, residents and ENGL113F A Nation of Immigrants? (FYS) visitors, colonizers and colonized, and from a variety of perspectives: fiction, America is a nation of immigrants. This ideological epithet has come to define literary journalism, travel accounts, and histories. -

"Archie's Girls?" Betty, Veronica, and the Rise of American Youth Culture, 1941-1950

ABSTRACT "ARCHIE'S GIRLS?" BETTY, VERONICA, AND THE RISE OF AMERICAN YOUTH CULTURE, 1941-1950 by Caroline Elizabeth Johnson This thesis uses the characters of Betty and Veronica of the Archie Comic series to explore the roles of adolescent females during the 1940s in the United States. The author utilizes feminist and art theory as well as relevant literature to argue that the writers of Archie Comics reflect and reify teenage experience through the characters of Betty and Veronica. Themes addressed include labor roles, dating habits, as well as teen involvement in consumer culture. By addressing the role of adolescent experience, the author hopes to expand conversations regarding women during the 1940s to include the impact of youth culture. The author concludes by suggesting Betty and Veronica represent a larger trend in American society regarding the way in which young women are conditioned to think and act in a particular manner via popular culture. "ARCHIE’S GIRL’S?” BETTY, VERONICA, AND THE RISE OF AMERICAN YOUTH CULTURE, 1941-1950 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Caroline Elizabeth Johnson Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2016 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Hamlin Reader: Dr. Mark Mckinney Reader: Dr. Stephen Norris ©2016 Caroline Elizabeth Johnson This Thesis titled "ARCHIE’S GIRL’S?” BETTY, VERONICA, AND THE RISE OF AMERICAN YOUTH CULTURE, 1941-1950 by Caroline Elizabeth Johnson has been approved for publication by The College of Arts and Science and Department of History ____________________________________________________ Dr. Kimberly Hamlin ______________________________________________________ Dr. -

KISS Bootlegs

Sten1972's KISS Live Recordings (updated 131209) DVD CD MP3 Audio NCB rating Comment Pre Album Shows 1973 6 16 Amityville, The Daisy X 1973 12 21 New York, Coventry X 1,5 tracks is filmed 1973 12 22 New York, Coventry X 4 Released on DVD 1973 12 31 New York, Academy Of Music X 2 Remastered version, missing a few seconds of "Deuce" "Kiss" Tour 1974 2 17 Long Beach, Civic Auditorium X 3 7- KISS Vision Remaster, not with original audio 1974 2 21 Los Angeles, Aquarius Theater X 5 Released on DVD The ABC In Concert, broadcasted 740329. Best version on Kissology 1974 3 25 Washington, Bayou Theater X 4 The 10.30 PM show. 2nd or 3rd gen upgrade (Tolvis) 1974 4 7 Detroit, Michigan Palace X 5 FM broadcast Master upgrade 1974 4 18 Memphis, La Fayette Music Hall X 4 FM broadcast Good recording but a lot of wobble. From silver CD + speed corrected 1974 4 29 Philadelphia, KYW-TV Studios X 5 Released on DVD The Mike Douglas show 1974 5 31 Long Beach, Civic Auditorium X X 4 FM broadcast My CD-version (vinyl transfer from 2010) doesn't include "Baby Let Me Go" 1974 7 16 Baton Rouge, Independence Hall X 4 Master upgrade 1974 8 4 South Bend, Morris Civic Auditorium X 3 Master upgrade, re-pitched "Hotter Than Hell" Tour 1974 10 18 Hammond, The Parthenon Theatre X 4 1974 10 21 East Lansing, The Brewery X 5 1974 10 25 Passaic, Capitol Theatre X PRO-shot This was filmed in B&W according to the owner of the club 1975 1 10 Portland, Paramount Theater X PRO-shot 1975 1 31 San Francisco, Winterland Ballroom X 5 10- Released on DVD Dodo's Upgrade from august 2006, better than the official release "Dressed To Kill" Tour 1975 3 21 New York, Beacon Theater X 2 Fasterpdiddy's cassette transfer from 2011, the 7.30 PM show 1975 3 24 Portland, Paramount Theater X PRO-shot 1975 4 1 California, NBC Studios X X 5 TV broadcast NBC Midnight Special 1975 4 19 Palatine, Fremd High School Gymnasium X 2 Tolvis version. -

Patron Saint of a World in Crisis: Early Modern Representations of St

PATRON SAINT OF A WORLD IN CRISIS: EARLY MODERN REPRESENTATIONS OF ST. FRANCIS XAVIER IN EUROPE AND ASIA by Rachel Miller BA, Kenyon College, 2005 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Rachel Miller It was defended on March 28, 2016 and approved by Christopher J. Nygren, Assistant Professor, History of Art and Architecture Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Assistant Professor, History of Art and Architecture Patrick Manning, Professor, History Dissertation Advisor: Kirk Savage, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Ann Sutherland Harris, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Rachel Miller 2016 iii PATRON SAINT OF A WORLD IN CRISIS: EARLY MODERN REPRESENTATIONS OF ST. FRANCIS XAVIER IN EUROPE AND ASIA Rachel Miller, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Recent historical studies have focused on the vital role that Catholic saints played after the Council of Trent, investigating how these holy figures were utilized to alleviate all manner of problems besetting the Post-Tridentine Church, emerging European nation states, and individual Catholics. My dissertation, however, approaches this issue from an art historical perspective, considering how images of St. Francis Xavier, the sixteenth-century Jesuit missionary, exercised considerable agency in an early modern world rife with global crisis. Specifically, I investigate Xaverian prints and paintings created in border zones of early modern Catholicism or in territories of the Iberian empires, particularly Antwerp, Goa, and Naples. -

An Improved Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm with Adaptable Parameters Khoa Duc Tran Nova Southeastern University, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks CEC Theses and Dissertations College of Engineering and Computing 2006 An Improved Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm with Adaptable Parameters Khoa Duc Tran Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Engineering and Computing. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Engineering and Computing, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/gscis_etd Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Khoa Duc Tran. 2006. An Improved Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm with Adaptable Parameters. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, Graduate School of Computer and Information Sciences. (888) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/gscis_etd/888. This Dissertation is brought to you by the College of Engineering and Computing at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CEC Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Improved Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm with Adaptable Parameters by Khoa Duc Tran A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Information Systems Graduate School of Computer and Information Sciences Nova Southeastern University 2006 We hereby certify that this dissertation, submitted by Khoa Duc Tran, conforms to acceptable standards and is fully adequate in scope and quality to fulfill the dissertation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________________________ ________________ Sumitra Mukherjee, Ph.D. Date Chairperson of Dissertation Committee _____________________________________________ ________________ Michael J. -

University-Of Hawa1'1 Library

_...--_.-.---- --._-_.------'- UNIVERSITY-OF HAWA1'1 LIBRARY THE DISCOURSES (RE)CONSTRUCTING THE SACRED GEOGRAPHY OF KAHO'OLAWE ISLAND, HAWAI'I A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN GEOGRAPHY DECEMBER 2002 by Allison A. Chun Dissertation Committee: Brian J. Murton, Chairperson Thomas Giambelluca Jon Goss Davianna McGregor Leslie Sponsel © Copyright 2002 by Allison A. Chun 1U ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Without help this research and dissertation would never have been completed.. I'm sure I have left out people, please accept my apologies. Much mahalo to my dissertation committee for their patience, encouragement, and support: to Les Sponsel and Davianna McGregor for their enthusiasm about my work; to Davi for providing reports and references and for keeping my facts straight; to Tom Giambelluca for giving me an opportunity to be part ofTeamHale-Boop, getting me backto Kaho'olawe after over fifteen years, and for keeping me involved in science; and to Jon Goss for always challenging me and making me think harder and more expansively than I would othe,rwise. Thanks especially to Brian Murton for transforming a basket case (me) after the trauma of my master's program. Mahalo to fellow geographers Ceil Roberts, Anne Fuller, Shirley Naomi Kanani Garcia, and John R. Egan for encouraging me to follow my heart and start this work on Kaho'olawe. Mahalo to Team Hale-Boop for camaraderie and sharing the experience of Kaho'olawe: Kanani, John, Alan Ziegler, Renee Louis, Fred Richardson, and Lyman Perry.