From Marginality to Congruity: Revisiting Marginality Through a Canonicity of Jain and Sikh Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Antiquty of Jainism

Jainism : An Image of Antiquity Published by Shri Jain Swetamber Khartargachha Sangha, Kolkata An analytical study of the historicity, antiquity and originality Chaturmass Prabandh Samiti of the religion of Jainism of a global perspective Sheetal Nath Bhawan Gauribari Lane Kolkata - 700 004 c Dr. Lata Bothra Printed in October 2006 by : Dr. Lata Bothra Type Setting Jain Bhawan Computer Centre P-25, Kalakar Street Kolkata - 700 007 Phone : 2268-2655 Printed by Shri Bivas Datta Arunima Printing Works 81, Simla Street Kolkata - 700 006 Shri Jain Swetamber Khartargachha Sangha, Kolkata Chaturmas Prabandh Samiti Price Kolkata Rupees Fifty only continents of the worlds, regarding Jainism. Jainism is a religion which is basically revolving within the PREFACE centrifugal force of Non-violence (Ahimsa), Non- receipt (Aparigraha) and the multizonal view Through the centuries, Jainism has been the (Anekantvad), through which the concept of global mainstay of almost every religion practiced on this planet. tolerance bloomed forth. Culturally, the evidences put forward by the There was a time splendour of Jainism, as a archaeological remnants almost all over the world starting religion and an ethical lifestyle was highly prevalent in from Egypt and Babylon to Greece and Russia inevitably the early days of our continental history. The remnants prove that Jainism in its asceticism was practiced from of antiquity portray a vivid image of the global purview prehistoric days. For what reason, till today, the Jaina whereby one can conclude that Jainism in different researchers have not raised their voice and kept mum forms and images was observed in different parts of about these facts, is but a mystery to me. -

JAINISM 101 a Scientific Approach

JAINISM 101 A Scientific Approach !!Jai Jinedra !! (Greetings) Hemendra Mehta Original by Sudhir M. Shah nmae Airh<ta[<. namo arihant˜õaÕ. nmae isÏa[<. namo siddh˜õaÕ. nmae Aayirya[<. namo ˜yariy˜õaÕ. nmae %vJHaya[<. namo uvajjh˜y˜õaÕ. nmae lae@ sVv£ sahU[<. namo loae savva s˜huõaÕ. Two Beliefs 1. Taught in Indian Schools 1. Hinduism is an ancient religion 2. Jainism is an off-shoot of Hinduism 3. Mahavir and Buddha started their religions as a protest to Vedic practices Two Beliefs 2. Jain Belief 1. Jainism is millions of year old 2. Jain religion has cycles of 24 Tirthankaras 1st Rishabhdev 24th Mahavirswami 3. Rishabhdev established agriculture, family system, moral standards, law, & religion Time Chart ARYANS ARRIVE RIKHAVDEV PERIOD MAHAVIR / BUDDHA INDUS VALLEY PERIOD CHRIST 6500 BCE 500 CE 1000 BCE 000 8,500 Yrs. ago 1500 Yrs. ago 3000 Yrs. ago 2000 Yrs. ago 2500 BCE 1500 BCE 500 BCE 4500 Yrs. ago 3500 Yrs. ago 2500 Yrs. ago Jain Religion Basic Information: • 10 million followers • Two major branches ¾ Digambar ¾ Shwetamber What is Religion? According to Mahavir swami “The true nature of a substance is a religion” Religion reveals • the true nature of our soul, and • the inherent qualities of our soul Inherent Qualities of our Soul Infinite Knowledge Infinite Perception Infinite Energy Infinite Bliss What is Jainism? A Philosophy of Living – Jains: Follow JINA, the conqueror of Inner Enemies – Inner Enemies (Kashays): • Anger (Krodh) • Greed (lobh) • Ego (maan) • Deceit (maya) – Causes: Attachment (Raag) and Aversion (Dwesh) -

Volume : 57 Issue No. : 57 Month : April, 2005

Volume : 57 Issue No. : 57 Month : April, 2005 ACHARYASHREE MAHAPRAJNA'S MESSAGE TO GENERAL MUSHARRAF DELIVERED BY LOKESH MUNI 'LOKESH' AT NEW DELHI ACHARVA MAHAPRAGYA NOMINATED FOR COMMUNAL HARMONY AWARD "Pakistan and India have similar problems and worries. We only can fight poverty, illiteracy and diseases rampant in our region, if our region is peaceful. Your efforts towards strengthening world peace and creating a non-violent society are commendable. I hold the belief that the ensuing atmosphere of peace will help us diverting the enormous defense expenditures to resolve the above-mentioned problems. To deal with contending issues the idea of Anekanta or non-absolutism, which talks of relative viewpoints, as given by Bhagwan Mahavira, can help. Meeting and dialogue are the first steps in this direction." April, New Delhi. The prestigious "Communal Harmony Award" will be given to Acharya Mahapragya, the founder of "Ahimsa Yatra" for His valuable contribution in the field of National Unity and Communal Harmony. According to the Foundation of National Communal Harmony, Govt. of India, this prestigious award for the year 2004 will be given to His Holiness Acharya Mahapragya at a grand function in the National Capital. This award is given for the unique contribution to the unity and communal harmony in the country. The Award Committee, presided by Shri Bhairon Singh Shekshawat, the Hon'ble Vice-President of India, has choosen Acharya Mahapragya for this award for His remarkable work among several nominees. In this award Rs. 2 lakh and a memorandum are presented. The spokesperson of Ahimsa Yatra Muni Lokprakash Lokesh has expressed his joy and said that this award would certainly be the award to the great values of Indian Culture. -

Jain World Brochure.Indd

Jainism is the science of living . Jainworld presents Jainism in a Unique Way Jainworld is a registered Foundation (Non- www.JainWorld.com JAINISM profit, Tax exempt, Trust. IRS # 501(c) (3) Jainism is one of the oldest living religions. Most envi- 48-1266905 ) in USA & other countries. All ronmentally friendly, ecology protecting and indepen- donations in USA are tax exempt. Your entry point dent religion with intrinsic respect and equality for all living beings (including animals). There is a provision for www.jainworld.com the highest level of enlightment for all in a scientific way. to the exciting world www.jainworld.net Man himself, and he alone, is responsible for all that is good or bad in his life. Actions, thought and speech along www.jainworld.org of Jainism with passions result in karmas. He must remove karmas or bear their consequences at maturity. (… one of the oldest living religion) Every soul is capable of attaining perfection (i.e. infinite perception, infinite knowledge, infinite power and infi- nite bliss) if it willfully exerts in that direction. This world in full of sorrow and trouble and it is quite necessary to achieve the aim of transcendental bliss by a sure method. No God, nor His prophet or beloved can interfere with life of others. The soul, and that alone is directly and nec- essarily responsible for all that it does. God is regarded as completely unconcerned with cre- ation of the universe or with any happening in the uni- verse. The universe goes of its own accord i.e. if follows laws of nature. -

Living Landscapes

Introduction Yoga and Landscapes This book explores the practice of Yoga in regard to a systematic technique of performing concentration on the five elements. It examines some ideas that also concerned the pre-Socratic philosophers of Greece. Just as Thales mused about water and Heraclitus extolled the power of fire, Indian thinkers, theologians, and liturgists reflected on how the elements interweave with one another and within the human body to create the raw material for the experience of life. In a real and metaphorical sense, according to Indian thought, we live in landscapes and landscapes live in us. For more than 3,500 years, India has identified earth, water, fire, air, and space as the foundational building blocks of external reality. Starting with literary praise of these elements in the Vedas, by the time of the Buddha, the Upaniṣads, and early Jainism, this acknowledgment had grown into a systematic reflection. This book examines both the descriptions of the elements and the very technical training tools that emerged so that human beings might develop regard and consideration for them. Hindus, Buddhists, and Jain Yogis explore the human-earth relationship each in their own way. For Hindus, nature emerges as a theme in the Vedas, the Upaniṣads, the Yoga literature, the epics, and the Purāṇas. The Yogis develop a mental discipline of sustained interiorization, known as pañca mahābhūta dhāraṇā (concentration on the five great elements) and as bhūta śuddhi (purification of the elements). The Buddha himself also taught a sequential meditation on the five elements. The Jains developed their own unique reflections on nature, finding life in particles of earth, water, fire, and air. -

Why Must There Be an Omniscient in Jainism?

5 WHY MUST THERE BE AN OMNISCIENT IN JAINISM? Sin Fujinaga 1. It is a well-known fact that the Jains deny the existence of God as a creator of this universe while the Hindus admit such existence. According to Jainism this universe has no beginning and no end, so no being has created it. On the other hand, the Jains are very eager to establish the existence of an omniscient person. Such a person is denied in the Hindu tradition. The Jain saviors or tirthaÅkaras are sometimes called bhagavan, a Lord. This word does not indicate a creator but rather means a respected person with all-pervading knowledge. Generally speaking, the omniscience of the tirthaÅkaras is such that they grasp each and every thing of the universe not only in the present time, but in the past and the future also. The view on the omniscience of tirthaÅkaras, however, is not ubiquitous in the Jaina tradition. Kundakunda remarks, “From the practical point of view an omniscient Lord perceives and knows all, while from the real point of view he perceives and knows his own soul.”1 Buddhism, another non-Hindu school of Indian philosophy, maintains that the founder Buddha is omniscient. In the Pali canon, the Buddha is sometimes described with the word savvaññu or sabbavid, both of which mean omniscient.2 But he is also said to recognize only the religious truth of dharma, more precisely, the four noble truths, caturaryasatya. This means that the omniscient Buddha does not need to know details of matters such as the number of insects in this world. -

Into the Future with Knowledge from Our Past

Into The Future With Knowledge from Our Past A Sourcebook for ‘VTT Scholar Quiz Competition 2007-08’ • Lessons from the Panchatantra • Potential of Ayurveda • Ancient Indian Technology • Srimad Bhagavad Gita & Lessons for Modern Management • Siri Bhoovalaya – A Unique Kannada Work of Cryptology • India’s Contribution to Linguistics • Yoga & Leadership Sponsors • Dakshinamnaya Sri Sharada Peetham, Sringeri • BMS College for Women, Bangalore • Sri Tirunarayana Trust, Bangalore For free distribution only. Not for Sale. Sourcebook and some of the presentations are also available at www.tirunarayana.org CONTENTS Preface 1 A Note to Students 2 A Brief Profile of Our Speakers at the Seminar 3 Into the Future with Knowledge from Our Past Lessons from the Panchatantra 5 Potential of Ayurveda 9 Ancient Indian Technology 13 Srimad Bhagavad Gita and Lessons for Modern Management 16 Siri Bhoovalaya – A Unique Kannada Work of Cryptology 19 India’s Contribution to Linguistics 25 Yoga & Leadership 28 PREFACE Students from twenty-two colleges and pre-university colleges, other than the BMS College for Women, which co-sponsored the programme, participated in the sixth annual Into the Future with Knowledge from Our Past seminar. A majority of the students (51.3%) was from the Commerce stream followed by Science (30.68%). However, it was encouraging to find that students from all educational streams, including professional courses like engineering, business management and computer applications, attended the seminar. While each of the topics dealt with in the seminar was rated the “most liked” by at least ten per cent of the students, Lessons from the Panchatantra (73.02%) and Srimad Bhagavad Gita and Lessons for Modern Management (30.68) appear to have been the most popular among students. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2017 Issue 12 CoJS Newsletter • March 2017 • Issue 12 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Muni Mahendra Kumar Ratnakumar Shah Professor J. Clifford Wright (University of Lyon) (Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, India) (Pune) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Dr James Laidlaw Dr Kanubhai Sheth Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Cambridge) (LD Institute, Ahmedabad) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Dr Basile Leclère Dr Kalpana Sheth Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (University of Lyon) (Ahmedabad) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Dr Jeffery Long Dr Kamala Canda Sogani Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Elizabethtown College) (Apapramśa Sāhitya Academy, Jaipur) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg Dr Jayandra Soni Dr Sean Gaffney (Independent Scholar) (University of Tübingen) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Luitgard Soni Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Munich) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Professor Christoph Emmrich Gerd Mevissen Dr Herman Tieken Dr James Mallinson (University of Toronto) (Berliner Indologische Studien) (Institut Kern, Universiteit Leiden) South Asia Department Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari Professor Werner Menski (University of Würzburg) (Harvard Divinity School) (Banaras Hindu University) School of Law Dr Sherry Fohr Dr Andrew More Dr Himal Trikha Professor Francesca Orsini (Converse College) (University of Toronto) (Austrian Academy of Sciences) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Catherine Morice-Singh Dr Tomoyuki Uno Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris) (Chikushi Jogakuen University) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Professor Hampa P. -

Four Anuyogs to Understand Jain

9/24/2018 Four Anuyogs to Understand Jain Religion Four Anuyogs to Understand Jain Religion Introduction: Lord Mahavir preached Jainism directly to the common people using common people’s language. After his Nirvan, his preaching of Jain philosophy, ethics, conduct, and spirituality are compiled in the Sutra form in the scriptures known as 11/12 Ang Agams. Pravin K. Shah The Agam sutras also reflected the culture, morality, and knowledge JAINA Education Committee base that existed among the common people of that time. 509 Carriage Woods Circle These religion sutras can be grouped into the four classes known as Raleigh NC 27607-3969 Anuyogs (Category of Explanation) Web - www.jainelibrary.org Email - [email protected] The knowledge, purpose, and limitation of each Anuyog is most essential for a clear understanding of Jain literature and its principles. Tele - 919-859-4994 Otherwise many meaningless misgivings will crop up in your mind about the Jain principles and its conduct. Four Anuyogs to Understand Jain Religion Four Anuyogs to Understand Jain Religion Four Anuyogs are: Four Anuyogs are (continue…..): 1. Prathamanuyoga or Kathanuyog 4. Dravyanuyoga (Dravya means "substance" or "existent") Literature relating to stories, information, fables, art, history, It includes sculpture, fiction, and mythology • Six universal substances (Jiva, Pudgal, Dharmastikay (Motion), 2. Karananuyoga or Ganitanuyog Adhamastikay (Rest), Space (Akas), Time (Kal) Literature relating to mathematics, structure and function of universe • Nine or seven tattvas. (loka), geography, rivers, mountains, Karma classification, and • Gunasthanak. Pure Soul and Impure Soul • 3. Charananuyoga or Charan-karananuyog Effect of Karma on Soul • Literature relating to principles of conduct and observances, the What are reasons behind Soul’s Impurity method of living; and the way of life in this world. -

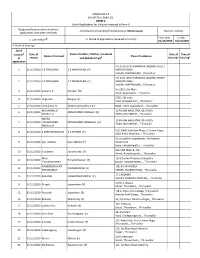

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Maduravoyal Revision identy applicaons have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Husband Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 1 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 2 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur No 2319, 5th Main 3 01/12/2020 Sumathi R Ramesh (H) Road, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur 2785, 5th main 4 01/12/2020 Jaiganesh Rangan (F) road, Ayyappakkam, , Thiruvallur 5 01/12/2020 Hemalatha D Dhatshinamoorthy K (H) 8640, TNHB, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur MOHAMMED 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 6 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED NORULLA (F) NASRULLA ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur HAJIRA 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 7 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED MOHAMMED NASRULLA (H) ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur NASRULLA C16, DABC Gokulam Phase 3, Sriram Nagar 8 01/12/2020 S SURIYAKRISHNAN K S SATHISH (F) Main Road, Nolambur, , Thiruvallur 42 sri Lakshmi apartments, 3rd Avenue 9 01/12/2020 sijo mathew biju mathew (F) millennium town, adayalampau, , Thiruvallur 312 VNR Milford, 7th 10 01/12/2020 Sundaram savarimuthu (F) Street, -

1-14 the Invention of Jainism a Short History of Jaina St

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 1, No. 1 (2005) 1-14 THE INVENTION OF JAINISM A SHORT HISTORY OF JAINA STUDIES Peter FlŸgel It is often said that Jains are very enthusiastic about erecting temples, shrines or upāśrayas but not much interested in promoting religious education, especially not the modern academic study of Jainism. Most practising Jains are more concerned with the ’correct’ performance of rituals rather than with the understanding of their meaning and of the history and doctrines of the Jain tradition. Self-descriptions such as these undoubtedly reflect important facets of contemporary Jain life, though the attitudes toward higher education have somewhat changed during the last century. This trend is bound to continue due to the demands of the information based economies of the future, and because of the vast improvements in the formal educational standards of the Jains in India. In 1891, the Census of India recorded a literacy rate of only 1.4% amongst Jain women and of 53.4% amongst Jain men.1 In 2001, the female literacy rate has risen to 90.6% and for the Jains altogether to 94.1%. Statistically, the Jains are now the best educated community in India, apart from the Parsis.2 Amongst young Jains of the global Jain diaspora University degrees are already the rule and perceived to be a key ingredient of the life-course of a successful Jain. However, the combined impact of the increasing educational sophistication and of the growing materialism amongst the Jains on traditional Jain culture is widely felt and often lamented. -

Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2015 Issue 10 CoJS Newsletter • March 2015 • Issue 10 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg (University of Lyon) (University of Tübingen) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Munich) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Gerd Mevissen Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (Berliner Indologische Studien) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Harvard Divinity School) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Professor Hampa P. Nagarajaiah (Independent Scholar) (University of Bangalore) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Thomas Oberlies Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Göttingen) Department of the Study of Religions Professor M.A. Dhaky Dr Leslie Orr Dr James Mallinson (Ame rican Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon) (Concordia University, Montreal) South Asia Department Professor Christoph Emmrich Dr Jean-Pierre Osier Professor Werner Menski (University of Toronto) (Paris) School of Law Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Dr Lisa Nadine Owen Professor Francesca Orsini (University of Würzburg) (University of North Texas) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Professor Olle Qvarnström Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (University of Lund) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Dr Pratapaditya