The Evolution of Payments United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release: Global Finance Names the World's Best Private

Global Finance Names The World’s Best Private Banks 2019 NEW YORK, October 22, 2018 — Global Finance magazine has announced its fourth annual World’s Best Private Banks Awards for 2019. A full report on the selections will appear in the December issue of Global Finance, and winners will be honored at an Awards Dinner at the Harvard Club of New York City on February 5th, 2019. About Global Finance The winners are those banks that best serve the specialized needs of Global Finance, founded in 1987, has a circulation of high-net-worth individuals as they seek to enhance, preserve and pass 50,050 and readers in 188 on their wealth. The winners are not always the biggest institutions, but countries. Global Finance’s rather the best—those with qualities that individuals rate highly when audience includes senior corporate and financial choosing a provider. officers responsible for making investment and strategic Global Finance’s editorial board selected the winners for the Private Bank decisions at multinational companies and financial Awards with input from executives and industry insiders. The editors institutions. Its website — also use information from entries submitted by banks, in addition to GFMag.com — offers analysis independent research, to evaluate a series of objective and subjective and articles that are the legacy of 31 years of experience factors. This year’s ratings were based on performance during the period in international financial covering July 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018. markets. Global Finance is headquartered in New York, with offices around the world. “Recent decades have minted unprecedented new ranks of millionaires Global Finance regularly selects and billionaires around the world, and they bring a new set of beliefs and the top performers among attitudes toward wealth. -

J.P. Morgan Private Bank Privacy Notice for U.S. Clients

The Private Bank Respecting and protecting client privacy have always been vital to our relationships with clients. The attached Privacy Notice, in a format recommended by federal regulators, describes how J.P. Morgan Private Bank keeps client information private and secure and uses it to serve you better. As shown, the J.P. Morgan companies that provide private banking services do not use client information for purposes not related to the Private Bank. Additionally, we keep your information under physical, electronic and procedural controls, and authorize our agents and contractors to get information about you only when they need it to do their work for us. The Private Bank uses information we have about you in order to make private banking products and services available to you through the Private Bank, including loans, deposits and investments, to meet your private banking needs. Using your information in this way, through the authorization you provided as part of your private banking application, may qualify you for account upgrades, improved client services and new service offerings based on our more complete knowledge of your relationship with the Private Bank. The Private Bank is a part of J.P. Morgan Asset & Wealth Management (the brand name for the asset and wealth management businesses of JPMorgan Chase & Co.) and provides private banking services for Private Bank clients. The Private Bank includes those units of JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., J.P. Morgan Trust Company of Delaware and J.P. Morgan Securities LLC dedicated to the Private Bank, as well as alternative investment funds offered through the Private Bank. -

GOLDMAN SACHS PRIVATE BANK SELECT a Digital Lending Solution

GOLDMAN SACHS PRIVATE BANK SELECT® A digital lending solution INTRODUCING GOLDMAN SACHS PRIVATE BANK SELECT Goldman Sachs Private Bank Select® (“GS Select”) is a securities-based lending solution that uses diversified, non- POTENTIAL USES retirement investment assets as collateral for your loan. Our digital platform allows you to quickly and seamlessly PERSONAL establish a revolving line of credit, providing easy access to liquidity. Our high-tech, high-touch servicing ensures easy Education mangement of your loan. Home renovations Tax obligations LOAN FEATURES BUSINESS SIZE: From $75,000 to $25 million, with an initial minimum loan advance requirement of $75,000 and subsequent drawdowns Acquisitions starting at $2,500 Liquidity USE: Any purpose other than purchasing or carrying margin stock Seed/startup capital TYPE: Revolving line of credit; you can borrow, repay, and re-borrow as needed BORROWER: Individuals and joint; irrevocable and revocable trusts POTENTIAL BENEFITS COLLATERAL: Non-retirement investment assets, including stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and exchange-traded funds Immediate and ongoing access to cash INTEREST RATE: 1-month LIBOR plus a spread determined by loan amount; LIBOR resets monthly Expedited loan processing, often within REPAYMENT: Interest only, payable monthly; principal can be 24 hours repaid at any time without penalty TERM: No maturity date; repayment can be demanded at any time High-tech, high-touch servicing and support by FEES: No application, origination, or annual fees phone, in person, and online DOCUMENTS: No personal financial statements, tax returns, paper applications, or other documents; trust documents not required in most states Securities-based loans may not be suitable for all borrowers/pledgors and carry a number of risks, including but not limited to the risk of a market downturn, tax implications if pledged securities are liquidated, and an increase in interest rates. -

Wealth Management and Private Banking Connecting with Clients and Reinventing the Value Proposition 2015 Contents

Wealth Management and Private Banking Connecting with clients and reinventing the value proposition 2015 Contents This document provides a perspective on the evolution of client value propositions in Wealth Management & Private Banking 3 Foreword 4 Scope and reach 6 Snapshot of key messages 8 Executive Summary 16 Strategic priorities 20 Products and services 26 Channels 36 Pricing 40 Our International Wealth Management & Private Banking practice at a glance 41 Our services 42 Key contributors 43 Contacts 2 Foreword Dear Readers, Deloitte and Efma are pleased to present you the results of our recent survey, providing a perspective on the evolution of client value propositions in Wealth Management and Private Banking. We invite you to consider the challenges facing the industry and how players are adapting their value proposition and connecting with clients in the new landscape. In the past few years, the Wealth Management and Private Banking industries have changed significantly. The financial crisis has increased investors’ sensitivity to risk, and the current low yield environment has made it more challenging to meet investors’ expectations of returns while limiting risk. In addition, the pressure for global tax transparency from governments around the world to crack down on tax evasion and tax fraud, has caused a significant shift from offshore to onshore wealth. The frontiers of demand are also being pushed beyond traditional borders, with emerging market players entering developed markets to follow their clients, and developed market players seeking growth outside of their home markets. This has resulted in volume losses (e.g. wealth repatriation) and/or decreased revenue margins as fiscal arbitrages have become obsolete and competition for onshore assets has increased. -

The Voice of the Private Banks

The voice of the private banks The Association of German Banks Banking world in figures €70,200,000,000,000 €70.2 trillion turnover in cashless payments in 2012 Number of online accounts million at private banks in 2012 18.4 80% million Private banks’ share securities accounts at of total export finance 10.6 private banks in 2010 million Number of bank cards 26.2 at private banks in 2011 Number of persons employed at the Association of German 176,000 Banks’ member banks in 2012 € billion Financial assets of private 4,939 households in 2012 Banking world in figures €2,012,329,000,000 Total assets of the Association of German Banks’ largest member bank in 2012: €2 trillion € million Total assets of the Association of 10 German Banks’ smallest member banks €1,044.9 billion German bank loans to private individuals in 2012 €1,377.6 billion German bank loans to businesses and self-employed persons in 2012 Over complaints handled since the launch of the 70,000 Ombudsman Scheme in 1992 participants in the Association of German Banks’ Schul|Banker 60,000 bank management game since 1998 Number of mentions of the Association of German Banks in the media in 2012 2,045 Number of participants in the Association of German Banks’ “Jugend und Wirtschaft” competition since it was launched in 2000 18,000 100.4 million bank customer cards in Germany in 2012 billion cashless payment 18.2 transactions in 2012 9,905 domestic branches of private banks in 2012 2,232 information notices to member banks in 2012 branches of private banks 388 abroad in 2012 Number of current accounts million at private banks in 2012 26.9 Market share of private banks, measured in terms 38% of the total volume of banking business in Germany The voice of the private banks The Association of German Banks 6 The voice of the private banks bankenverband Foreword Responsible lobbyist prosperity in Germany. -

RMB Private Bank Pricing Guide 2017

HOME Introduction PRICING GUIDE Ways to bank 1 July 2017 – 30 June 2018 eBucks Rewards and benefits RMB Private Bank accounts RMB Private Bank Fusion Account Cheque Account & Single Facility RMB Private Bank Credit Card Offshore Banking & Global Accounts Foreign Exchange Private Business Account Single Fee Pricing Option Pay-As-You-Use Pricing Option Cash Bundle Home Loan, Structured Loan, Securities Based Loan and Single Credit Facility Important information Standard Terminology Contact us RMB Private Bank - a division of FirstRand Bank Limited. Authorised Financial Services and Credit Provider (NCRCP20). Reg. No. 1929/001225/06. Home INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION YOUR PARTNER ON YOUR WEALTH AND solutions and advice for you. We understand Ways to bank LEGACY MANAGEMENT JOURNEY the intricacies of wealth and will help guide you through the complexities of today’s financial world while complementing your eBucks Rewards and benefits This pricing guide will assist you in At RMB Private Bank we aim to give you an lifestyle through our award-winning eBucks understanding your bank charges and help expert view of your finances coupled with Rewards programme so that you can enjoy, RMB Private Bank accounts you make banking choices that enable you to insightful, advice-led solutions for you and manage, protect and grow your wealth for get the most out of banking with us. your family. At the heart our engagement RMB Private Bank Fusion Account future generations. All fees quoted are VAT inclusive and are model is your Private Banker, together with effective -

Pa Perspectives on Nordic Financial Services

PA PERSPECTIVES ON NORDIC FINANCIAL SERVICES Autumn Edition 2017 CONTENTS The personal banking market 3 Interview with Jesper Nielsen, Head of Personal Banking at Danske bank Platform thinking 8 Why platform business models represent a double-edged sword for big banks What is a Neobank – really? 11 The term 'neobanking' gains increasing attention in the media – but what is a neobank? Is BankID positioned for the 14future? Interview with Jan Bjerved, CEO of the Norwegian identity scheme BankID The dance around the GAFA 16God Quarterly performance development 18 Latest trends in the Nordics Value map for financial institutions 21 Nordic Q2 2017 financial highlights 22 Factsheet 24 Contact us Chief editors and Nordic financial services experts Knut Erlend Vik Thomas Bjørnstad [email protected] [email protected] +47 913 61 525 +47 917 91 052 Nordic financial services experts Göran Engvall Magnus Krusberg [email protected] [email protected] +46 721 936 109 +46 721 936 110 Martin Tillisch Olaf Kjaer [email protected] [email protected] +45 409 94 642 +45 222 02 362 2 PA PERSPECTIVES ON NORDIC FINANCIAL SERVICES The personal BANKING MARKET We sat down with Jesper Nielsen, Head of Personal Banking at Danske Bank to hear his views on how the personal banking market is developing and what he forsees will be happening over the next few years. AUTHOR: REIAR NESS PA: To start with the personal banking market: losses are at an all time low. As interest rates rise, Banking has historically been a traditional industry, loss rates may change, and have to be watched. -

Interbank GIRO Is an Automated Payment Service Which Allows You to Make Monthly Payment to Your ICBC Credit Card Account from Your Designated Bank Account Directly

Interbank GIRO Frequently Asked Questions: 1. What is Interbank GIRO? Interbank GIRO is an automated payment service which allows you to make monthly payment to your ICBC Credit Card account from your designated bank account directly. The amount will be deducted from your designated bank account and paid to ICBC every month. All you need to do is to ensure that the designated bank account has sufficient funds every month. 2. What is the benefit of using Interbank GIRO? Interbank GIRO is a convenient, paperless and cashless payment method. It enables you to make hassle-free monthly payments to ICBC through your designated bank account. There are also no fees charged for the setup. 3. Are there any additional charges for signing up for Interbank GIRO? There are no fees charged for the setup of Interbank GIRO. 4. How can I apply for Interbank GIRO? Simply fill up the Interbank GIRO form, and submit to Credit Card Department. 5. Which banks can I use for Interbank GIRO? You can use any bank that supports Interbank GIRO. 6. How long is the Interbank GIRO application Processing Time? Interbank GIRO applications may take up to 60 days to process, including the processing time required by the deducting bank. We will notify you of your application status as soon as possible. 7. How do I submit the Interbank GIRO form to ICBC Credit Card Department? You can mail the duly signed Original Interbank GIRO form to ICBC Credit Card Department by using the Business Reply Service Envelope attached. Please do not fax the Interbank GIRO form or email the scanned copy of the Interbank GIRO form as the designated bank requires the original signature for verification. -

Building a Customer-Centric Digital Bank in Singapore: It Takes an Ecosystem

White Paper Digital Banking EQUINIX AND KAPRONASIA BUILDING A CUSTOMER-CENTRIC DIGITAL BANK IN SINGAPORE: IT TAKES AN ECOSYSTEM Contents The dawn of digital banking in the Lion City Defining a value proposition . 2 No digital bank, in the purest sense of the term, Digital banking in Singapore amid COVID-19 . 4 currently exists in Singapore. While there are many fintechs, most provide only digital financial services The digital banking opportunity: that do not require a banking license: digital wallet retail and corporate . 5 services, cross-border payments and various virtual- asset-focused services. A digital bank (also known Key success factors for digital banks . 7 as a “neobank” or “virtual bank”) differs in that it is licensed to both accept customer deposits and issue 1. Digital agility to support a better loans, whether to retail customers, corporate customers customer experience. .7 or both. Singapore’s financial regulator, the Monetary 2. Favorable cost structure. .8 Authority of Singapore (MAS) plans to release five digital bank licenses in total and will announce the 3. Optimizing security .............................8 successful licensees in the second half of 2020. The licensed digital banks will likely then launch in mid-2021. Conclusion: The ecosystem opportunity . 10 While many less-developed Southeast Asian economies are leveraging digital banks to focus on financial inclusion, the role of digital banks in Singapore will be slightly different and focused on driving innovation. Bringing together traditional financial services firms, fintechs, other tech companies and even telecoms Singapore will become one of the firms, digital banks could act as a catalyst for financial focal points of Asia’s digital banking innovation in Singapore and help the city-state maintain evolution when the city-state awards its competitive advantage as a regional fintech hub. -

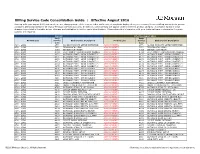

Billing Service Code Consolidation Guide | Effective August 2016

Billing Service Code Consolidation Guide | Effective August 2016 Starting with your August 2016 statement, we are changing some of the service codes and service descriptions displayed on your Treasury Services Billing statement to provide consistent billing standards for all of your Treasury Services accounts. In addition, some services will appear under a different product category. A complete listing of these changes is provided in the table below. Changes are highlighted in red for easier identification. Please share this information with your technical team to determine if system updates are required. Current Effective August 2016 Bank Bank Product Line Service Bank Service Description Product Line Service Bank Service Description Code Code ACH - GIRO 2770 ACHDD MANDATE SETUP(INITIATOR) ACH PAYMENTS 2770 ACHDD MANDATE SETUP(INITIATOR) ACH - GIRO 3971 ZENGIN ACH (LOW) ACH PAYMENTS 3971 ZENGIN ACH (LOW) ACH - GIRO 4093 ZENGIN ACH (HIGH) ACH PAYMENTS 4093 ZENGIN ACH (HIGH) ACH - GIRO 4094 ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CHARGE ACH PAYMENTS 4094 ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CHARGE ACH - GIRO 4170 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 1 ACH PAYMENTS 4170 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 1 ACH - GIRO 4171 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 2 ACH PAYMENTS 4171 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 2 ACH - GIRO 4172 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 3 ACH PAYMENTS 4172 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 3 ACH - GIRO 4173 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 4 ACH PAYMENTS 4173 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 4 ACH - GIRO 4174 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) 5 ACH PAYMENTS 4174 OUTWARD PYMT - GIRO (URGENT) -

Payment Services Guide

CitiDirect® Online Banking Payments Services Guide March 2004 Proprietary and Confidential These materials are proprietary and confidential to Citibank, N.A., and are intended for the exclusive use of CitiDirect ® Online Banking customers. The foregoing statement shall appear on all copies of these materials made by you in whatever form and by whatever means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or in any information storage system. In addition, no copy of these materials shall be disclosed to third parties without express written authorization of Citibank, N.A. Table of Contents Overview .......................................................................................................................................1 Payments Services....................................................................................................................1 Creating Service Requests From Transaction Lookup..............................................................2 Creating Service Requests From Transaction Details ..............................................................9 Modifying Service Requests....................................................................................................14 Authorizing or Deleting Service Requests...............................................................................16 Viewing Service Request Transactions...................................................................................18 Disclaimer ...................................................................................................................................20 -

Investec Bank Plc Banking Relationship Agreement

INVESTEC BANK PLC BANKING RELATIONSHIP AGREEMENT 1 Contents 1. Welcome to your Relationship Agreement 4 2. Protecting your account 7 3. Giving us instructions 8 4. Using your account 10 5. Using banking services 17 6. Debit cards 17 7. Third Party Providers 18 8. Borrowing on your account 18 9. Changing the terms of your agreement 20 10. Liability 21 11. Suspending your account, or stopping your use of banking services 24 12. Other events that might happen 25 13. Closing accounts 26 14. If you fail to make a payment to us (set-off) 27 15. Contacting you 28 16. General terms 29 Definitions 31 Charges Sheet 32 Additional Conditions for the Currency Access Account 33 Additional Conditions for the Direct Reserve Account 35 Additional Conditions for the E-asy Access Account 36 Additional Conditions for Fixed Term Deposits 37 Additional Conditions for the Investec Access Account 39 Additional Conditions for the Investec Cash ISA 40 Additional Conditions for the Investec High 5 Issue 2 Account 43 Additional Conditions for the Private bank account 45 The Private bank account glossary 49 Additional Conditions for the SIPP and SSAS Saver 51 2 Additional Conditions for the Specialist Access Account 53 Additional Conditions for the Voyage account 55 The Voyage account glossary 60 Additional Conditions for the Voyage Reserve Account 62 Additional Conditions for the 2 Year Double Base Bond 63 Additional Conditions for the 3 Month Reserve Account 65 Additional Conditions for the 3 Year Base Rate Plus 66 Additional Conditions for the 3 Year Base Rate Plus (release 2) 68 Additional Conditions for the 5 Year Step Up Bond 70 Additional Conditions for Notice Plus 72 3 1.