Cooperative Catch Shares

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goose Barnacle

Fisheries Pêches and Oceans et Océans DFO Science Pacific Region Stock Status Report C6-06 (1998) Rostral - Carinal Length GOOSE BARNACLE Background The Fishery The goose barnacle (Pollicipes polymerus) ranges from southern Alaska to Baja California on the First Nations people have long used goose upper two-thirds of the intertidal zone on exposed or barnacles as food. Goose barnacles have semi-exposed rocky coasts. been commercially harvested sporadically since the 1970s, and continuously since Goose barnacles are hemaphrodidic (one individual has both sexes). They mature at 14-17 mm rostral- 1985. They are hand harvested with various carinal length or one to 3 years of age. Spawning is design cutting tools, and then stored and from late April to early October, with peak spawning shipped as live product. in July, producing 475,000 - 950,000 embryos/adult /season. Larvae are planktonic for 30-40 days, and Goose barnacles have long been recognized settle in suitable habitat at 0.5mm length. as a delicacy in Spain, Portugal and France. Growth is rapid the first year (11-15 mm rostral- The major market for Canadian west coast carinal length) and slows thereafter to 1-3 mm/yr. goose barnacles is Spain, particularly the Maximum size is 45 mm rostral-carinal length, 153 Barcelona area. The market price in Spain peduncle length. Maximum age is unknown. The varies with season and availability from other muscular stalk (peduncle) is analogous to the sources. muscular tail of shrimp, prawns or lobster. Harvesters use a modified cutting and prying tool to Accessibility to the wave swept areas of the free goose barnacles from their substrates and west coast of Vancouver Island (Statistical collect and sort them by hand. -

Five Nations Multi-Species Fishery Management Plan, April 1, 2021

PACIFIC REGION FIVE NATIONS MULTI-SPECIES FISHERY MANAGEMENT PLAN April 1, 2021 – March 31, 2022 SALMON, GROUNDFISH, CRAB, PRAWN, GOOSENECK BARNACLE, AND SEA CUCUMBER Version 1.0 Genus Oncorhynchus Pacific Halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepsis) Gooseneck Barnacle (Pollicipes polymerus) Dungeness crab Sea Cucumber Spot Prawn (Cancer magister) (Apostichopus californicus) (Pandalus platyceros) Fisheries and Oceans Pêches et Océans Canada Canada This Multi-species Fishery Management Plan (FMP) is intended for general purposes only. Where there is a discrepancy between the FMP and the Fisheries Act and Regulations, the Act and Regulations are the final authority. A description of Areas and Subareas referenced in this FMP can be found in the Pacific Fishery Management Area Regulations, 2007. This FMP is not a legally binding instrument which can form the basis of a legal challenge and does not fetter the Minister’s discretionary powers set out in the Fisheries Act. 9-Apr.-21 Version 1.0 Front cover drawing (crab) by Antan Phillips, Retired Biologist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada Front cover drawing (gooseneck barnacle) by Pauline Ridings, Biologist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada Front cover drawing (sea cucumber) by Pauline Ridings, Biologist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada This page intentionally left blank 2021/22 Five Nations Multi-species Fishery Management Plan V. 1.0 Page 2 of 123 9-Apr.-21 Version 1.0 FMP Amendment Tracking Date Version Sections revised and details of revision. 2021-04-09 April 9, 2021 (1.0) Initial 2021/22 Five Nations Multi-species Fishery Management Plan V. 1.0 Page 3 of 123 9-Apr.-21 Version 1.0 CONTENTS Glossary and List of Acronyms .................................................................................................. -

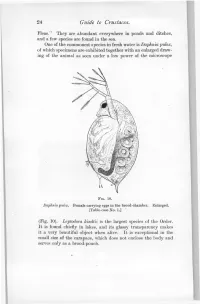

24 Guide to Crustacea

24 Guide to Crustacea. Fleas." They are abundant everywhere in ponds and ditches, and a few species are found in the sea. One of the commonest species in fresh water is Daphnia pulex, of which specimens are exhibited together with an enlarged draw- ing of the animal as seen under a low power of the microscope FIG. 10. Daphnia pulex. Female carrying eggs in the brood-chamber. Enlarged. [Table-case No. 1.] (Fig. 10). Leptodora kindtii is the largest species of the Order. It is found chiefly in lakes, and its glassy transparency makes it a very beautiful object when alive. It is exceptional in the small size of the carapace, which does not enclose the body and serves only as a brood-pouch. Ostracoda. 25 Sub-class II.—OSTRACODA. (Table-ease No. 1.) The number of somites, as indicated by the appendages, is smaller than in any other Crustacea, there being, at most, only two pairs of trunk-limbs behind those belonging to the head- region. The carapace forms a bivalved shell completely en- closing the body and limbs. There is a large, and often leg-like, palp on the mandible. The antennules and antennae are used for creeping or swimming. The Ostracoda (Fig. 10) are for the most part extremely minute animals, and only one or two of the larger species can be exhibited. They occur abundantly in fresh water and in FIG. 11. Shells of Ostracoda, seen from the side. A. Philomedes brenda (Myodocopa) ; B. Cypris fuscata (Podocopa); ('. Cythereis ornata (Podocopa): all much enlarged, n., Notch characteristic of the Myodocopa; e., the median eye ; a., mark of attachment of the muscle connecting the two valves of the shell. -

Local Catch Roundtable NOAA Science Center Monday, May 7, 2012

Local Catch Roundtable NOAA Science Center Monday, May 7, 2012 PARTICIPANTS Thomas Hymel, Marine Extension Agent, Louisiana Sea Grant Kim Chauvin, Owner, Mariah Jade Seafood Company Amber Von Harten, Marine Fisheries Specialist, South Carolina Sea Grant Madeleine HallArber, Marine Anthropologist, MIT Sea Grant Peter Philips, President of Philips Publishing Group Pete Granger, Program Leader‐Marine Advisory Services, Washington Sea Grant Jack Thigpen, Extension Director, North Carolina Sea Grant Sara Mirabilio, Fisheries Specialist, North Carolina Sea Grant Karen Willis Amspacher, Director, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center Fen Hunt, USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture Josh Stoll, NOAA Fisheries Office of Policy Katie Semon, NOAA Fisheries Office of Communications Galen Tromble, Chief of Domestic Fisheries, NOAA Fisheries Office of Sustainable Fisheries Leon Cammen, Director, National Sea Grant College Program Gene Kim, Program Director for Aquaculture at the National Sea Grant Office Ayeisha Brinson, Economist, NOAA Fisheries Office of Science and Technology, Economics and Social Analysis Division Additional attendees: Wendy Morrison, NOAA Fisheries, Office of Sustainable Fisheries Chris Hayes, NOAA National Sea Grant Office Mike Liffmann, NOAA National Sea Grant Office Amy Painter, NOAA National Sea Grant Office Emily Susko, NOAA National Sea Grant Office Wan Jean Lee, NOAA National Sea Grant Office Amy Scaroni, NOAA National Sea Grant Office OPENING REMARKS Leon Cammen, Director of the National Sea Grant College Program Leon welcomed the round table participants, expressing appreciation for the work that they do to maintain economic well‐being and a traditional way of life in coastal communities. Sea Grant programs around the country are working to help fishermen generate revenue, and to survive in what is now a global seafood market. -

Marine Invertebrates of Digha Coast and Some Recomendations on Their Conservation

Rec. zool. Surv. India: 101 (Part 3-4) : 1-23, 2003 MARINE INVERTEBRATES OF DIGHA COAST AND SOME RECOMENDATIONS ON THEIR CONSERVATION RAMAKRISHNA, J A YDIP SARKAR * AND SHANKAR T ALUKDAR Zoological Sruvey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata 700 053, India INTRODUCTION The ftrst study on marine fauna of Digha coast is known from the work of Bharati Goswami during 1975-87 (Bharati Goswami, 1992). Other workers, viz., Bairagi, Bhadra, Mukhopadhyaya, Misra, Reddy (1995); Subba Rao et. al., (1992, 1995); Talukdar et. al., (1996); Ramakrishna and Sarkar (1998); Sastry (1995, 1998) and Mitra et. al., (2002) also reported some marine invertebrates under different faunal groups from Hughly-Matla estuary, including Digha. But uptil recently there is no comprehensive updated list of marine invertebrates from Digha coast and adjoining areas. With the establishment of Marine Aquarium and Research Centre, Digha in the year 1990, opportunity was launched for undertaking an extensive exploration and studying seasonal changes that have been taken place on the coastal biodiversity in this area. Accordingly, the authors of the present work, started collecting the detailed faunal infonnation from Digha and adjoining coastal areas [Fig. 2 and 3]. During the study, it has transpired that exploitation of coastal resources has very abruptly increased in recent years. Several new fishing gears are employed, a number of new marine organisms are recognized as commercial fish and non fish resources. Also, the number of trawlers has increased to a large extent. The present paper based on the observations from 1990 to 2000 (including the current records upto January, 2002), is an uptodate database for the available species of marine invertebrates from this area. -

Zootaxa, Pollicipes Caboverdensis Sp. Nov. (Crustacea: Cirripedia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal do Conhecimento Zootaxa 2557: 29–38 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Pollicipes caboverdensis sp. nov. (Crustacea: Cirripedia: Scalpelliformes), an intertidal barnacle from the Cape Verde Islands JOANA N. FERNANDES1, 2, 3, TERESA CRUZ1, 2 & ROBERT VAN SYOC4 1Laboratório de Ciências do Mar, Universidade de Évora, Apartado 190, 7520-903 Sines, Portugal 2Centro de Oceanografia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal 3Section of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA 4Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Geology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Dr, San Francisco, CA 94118-4599, USA Abstract Recently, genetic evidence supported the existence of a new species of the genus Pollicipes from the Cape Verde Islands, previously considered a population of P. pollicipes. However, P. pollicipes was not sampled at its southern limit of distribution (Dakar, Senegal), which is geographically separated from the Cape Verde Islands by about 500 km. Herein we describe Pollicipes caboverdensis sp. nov. from the Cape Verde Islands and compare its morphology with the other three species of Pollicipes: P. pollicipes, P. elegans and P. po l y me ru s . Pollicipes pollicipes was sampled at both the middle (Portugal) and southern limit (Dakar, Senegal) of its geographical distribution. The genetic divergence among and within these two regions and Cape Verde was calculated through the analysis of partial mtDNA CO1 gene sequences. -

Fish Bulletin 161. California Marine Fish Landings for 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California

UC San Diego Fish Bulletin Title Fish Bulletin 161. California Marine Fish Landings For 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/93g734v0 Authors Pinkas, Leo Gates, Doyle E Frey, Herbert W Publication Date 1974 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE RESOURCES AGENCY OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME FISH BULLETIN 161 California Marine Fish Landings For 1972 and Designated Common Names of Certain Marine Organisms of California By Leo Pinkas Marine Resources Region and By Doyle E. Gates and Herbert W. Frey > Marine Resources Region 1974 1 Figure 1. Geographical areas used to summarize California Fisheries statistics. 2 3 1. CALIFORNIA MARINE FISH LANDINGS FOR 1972 LEO PINKAS Marine Resources Region 1.1. INTRODUCTION The protection, propagation, and wise utilization of California's living marine resources (established as common property by statute, Section 1600, Fish and Game Code) is dependent upon the welding of biological, environment- al, economic, and sociological factors. Fundamental to each of these factors, as well as the entire management pro- cess, are harvest records. The California Department of Fish and Game began gathering commercial fisheries land- ing data in 1916. Commercial fish catches were first published in 1929 for the years 1926 and 1927. This report, the 32nd in the landing series, is for the calendar year 1972. It summarizes commercial fishing activities in marine as well as fresh waters and includes the catches of the sportfishing partyboat fleet. Preliminary landing data are published annually in the circular series which also enumerates certain fishery products produced from the catch. -

The Effectiveness of Fishery Cooperative Institutions Pjaee, 17 (4) (2020)

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FISHERY COOPERATIVE INSTITUTIONS PJAEE, 17 (4) (2020) THE EFFECTIVENESS OF FISHERY COOPERATIVE INSTITUTIONS Lis M. Yapanto¹, Dahniar Th. Musa², Funco Tanipu³, Arfiani Rizki Paramata⁴, Munirah Tuli⁵ 1,4,5Faculty of Fisheries and Marine, State University of Gorontalo. Indonesia 2Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Tanjungpura University Pontianak, Indonesia 3Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, State University of Gorontalo. Indonesia Correspondence author: [email protected] Lis M. Yapanto, Dahniar Th. Musa, Funco Tanipu, Arfiani Rizki Paramata, Munirah Tuli. The Effectiveness Of Fishery Cooperative Institutions-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(4), 1329-1338. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Cooperatives, Fisheries, Institutions, Welfare, Economic Actors ABSTRACT This research was conducted based on a literature study of several articles and books, carried out from July 2020 to September 2020. The writing of this article was done by collecting information from various sources, analyzing and then concluding. The existence of fisheries cooperatives is very helpful in meeting the needs of its members and the surrounding community such as basic assistance, capital, credit, or borrowing, sales, fishermen's needs in fishing and so on. The existence of cooperatives also provides benefits in other fields, such as education, development of community infrastructure, health and various community activities, especially fishermen. INTRODUCTION Many problems faced, the fisheries sector. such as physical damage to coastal and aquatic ecosystem habitats, decreasing water quality, overfishing, low handling and processing of fishery products, unstable prices for production factors, increasingly fierce market competition, poverty and capital problems. In addition, the low quality of human resources and mastery of technology also adds to the problem of fisheries development. -

Barnacle Paper.PUB

Proc. Isle Wight nat. Hist. archaeol. Soc . 24 : 42-56. BARNACLES (CRUSTACEA: CIRRIPEDIA) OF THE SOLENT & ISLE OF WIGHT Dr Roger J.H. Herbert & Erik Muxagata To coincide with the bicentenary of the birth of the naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1889) a list of barnacles (Crustacea:Cirripedia) recorded from around the Solent and Isle of Wight coast is pre- sented, including notes on their distribution. Following the Beagle expedition, and prior to the publication of his seminal work Origin of Species in 1859, Darwin spent eight years studying bar- nacles. During this time he tested his developing ideas of natural selection and evolution through precise observation and systematic recording of anatomical variation. To this day, his monographs of living and fossil cirripedia (Darwin 1851a, 1851b, 1854a, 1854b) are still valuable reference works. Darwin visited the Isle of Wight on three occasions (P. Bingham, pers.com) however it is unlikely he carried out any field work on the shore. He does however describe fossil cirripedia from Eocene strata on the Isle of Wight (Darwin 1851b, 1854b) and presented specimens, that were supplied to him by other collectors, to the Natural History Museum (Appendix). Barnacles can be the most numerous of macrobenthic species on hard substrata. The acorn and stalked (pedunculate) barnacles have a familiar sessile adult stage that is preceded by a planktonic larval phase comprising of six naupliar stages, prior to the metamorphosis of a non-feeding cypris that eventually settles on suitable substrate (for reviews on barnacle biology see Rainbow 1984; Anderson, 1994). Additionally, the Rhizocephalans, an ectoparasitic group, are mainly recognis- able as barnacles by the external characteristics of their planktonic nauplii. -

An Evaluation of the Business Peliormance of Fishery Cooperative

An Evaluation of the Business JANUARY 2007 225 providing genuine support to fishers. The present study is conducted in ... Peliormance of Fishery Vasai taluka of Thane district, Maharashtra to evaluate the performance and their role in fishery cooperatives in terms of their business activities. Ratio analysis technique was used to evaluate the business performance Cooperative Societies .in Vasai or primary fishery cooperatives of Vasai taluka. Result $howed ~hat gross profi ratio and operating ratio of majority of societies are unsatTstactory Taluka of Thane District) whereas net profi ra:~lo and efficiency ratio are satisfactory In most of the cases. Maharashtra Introduction Fishermen community in India is amongst the weakest sections of the community. Illiteracy, poverty, and lack of knowledge of latest technologies are major contributing factors to their retarding socio-economic growth. This vicious circiL is further strengthened by lack of institutional & SMITHA R. NAIR, S.K. PANDEY" ARPITA SHARMA support both in infrastructure and finance. Consequently, middlemen who SHYAM S. SALlM* act as money iendersftraders subject fishermen tp explo;ta;tion. Fishermen discovered thatt.he cooperattlves could save them from the exploitation and Imp rov~ thei r sQcio··economic cQnditlons. The fishery cooperatives have made impressive progress particularly after introduction of Five Year Plans. There had been remendous growth In establishment of different levels of cooperative societies, in India. The most common structure of fishery coopergtives in different states of India is three tier, starting from primary cooperatives at village level, central federations of district/regional level, apex federation at state level and FISHCOPFED at national level (Mishra, 1997). -

Supporting Statement Alaska Cooperatives in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands Omb Control No.: 0648-0401

SUPPORTING STATEMENT ALASKA COOPERATIVES IN THE BERING SEA AND ALEUTIAN ISLANDS OMB CONTROL NO.: 0648-0401 INTRODUCTION National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) manages the groundfish fisheries in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands Management Area (BSAI). The North Pacific Fishery Management Council (Council) prepared the Fishery Management Plan for Groundfish of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands Management Area (FMP) under the authority of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, 16 U.S.C. 1801 et seq. (Magnuson-Stevens Act) as amended by Public Law 109-479. Regulations implementing the FMP appear at 50 CFR part 679. On October 21, 1998, the President signed into law the American Fisheries Act, 16 U.S.C. 1851 (AFA) which imposed major structural changes on the BSAI pollock fishery. Amendment 84 proposes a management program, called the salmon bycatch reduction inter- cooperative agreement (ICA), which would enable the pollock fleet to utilize its internal cooperative structure to reduce salmon bycatch. If Amendment 84 is approved and implemented, salmon savings area closures would not apply to vessels that operate under a salmon bycatch reduction ICA. BACKGROUND Pacific salmon are caught incidentally in the BSAI trawl fisheries, especially in the pollock fishery. Of the five species of Pacific salmon, Chinook salmon (Onchorynchus tshawytscha) and chum salmon (O. keta) are most often incidentally caught in the pollock fishery. Pacific salmon are placed into two categories for purposes of salmon bycatch management: Chinook and non- Chinook. The non-Chinook category is comprised of chum, sockeye (O. nerka), pink (O. -

Report of the Benthos Ecology Working Group (BEWG)

ICES BEWG 2005 Report ICES Marine Habitat Committee ICES CM 2005/E:07 REF. ACME, ACE, B Report of the Benthos Ecology Working Group (BEWG) 19–22 April 2005 Copenhagen, Denmark International Council for the Exploration of the Sea Conseil International pour l’Exploration de la Mer H.C. Andersens Boulevard 44–46 DK-1553 Copenhagen V Denmark Telephone (+45) 33 38 67 00 Telefax (+45) 33 93 42 15 www.ices.dk [email protected] Recommended format for purposes of citation: ICES. 2005. Report of the Benthos Ecology Working Group, 19–22 April 2005, Copenhagen, Denmark. ICES CM 2005/E:07. 88 pp. For permission to reproduce material from this publication, please apply to the General Secre- tary. The document is a report of an Expert Group under the auspices of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea and does not necessarily represent the views of the Council. © 2005 International Council for the Exploration of the Sea ICES BEWG 2005 Report | i Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................1 1 Opening and local organisation......................................................................................3 1.1 Appointment of Rapporteur.....................................................................................3 1.2 Terms of Reference .................................................................................................3 2 Adoption of agenda..........................................................................................................3