Enclaves As Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

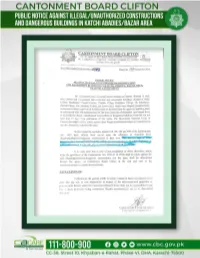

Public Notice Against Illegal / Unauthorized Constructions

CANTONMENT BOARD CLIFTON CC-38, Street 10, Kh-e-Rahat, Phase-VI, DHA, Karachi-75500 Ph. # 35847831-2, 35348774-5, 35850403, 35348784, Fax 5847835 Website: www.cbc.gov.pk _____________________________________ No. CBC/Lands/Publication/012/ Dated the 16 December 2020. PUBLIC NOTICE AGAINST ILLEGAL/UNAUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION AND DANGEROUS BUILDINGS IN KATCHI ABADIES/BAZAR AREA CLIFTON CANTONMENT All concerned/owners/occupants/lessees/tenants are hereby directed in their own interest and convenience that residential and commercial buildings situated at Delhi Colony, Madniabad, Punjab Colony, Chandio Village, Bukhshan Village, Ch. Khaliq-uz-Zaman Colony, Pak Jamhoria Colony and Lower Gizri, which were illegally/unauthorizedly constructed without approval of building plans or deviated from the approved building plans or constructed with sub- standard material and may cause loss of properties and human lives, to demolish the illegal, unauthorized constructions or dangerous buildings forthwith but not later than 15 days from publication of this notice. The Honourable Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken serious notice against these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions and also directed to demolish the same. In this regard the requisites notices U/S 126, 185 and 256 of the Cantonments Act, 1924 have already been served upon the offenders to demolish these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions at their own. The details of such properties are as under:- DEHLI COLONY NO.01 S. Property Name of present owner Violation/ status of Name of original Lessee No. No. as per record of CBC illegal construction 1 A-01/01 Mr. Noor Bat Khan Mrs. Abida Noor Ground + 7th Floor 2 A-01/02 Mr. -

List of Shareholders Whose Dividend Is Witheld Due to Non Provision of Valid Iban and Cnic

LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE DIVIDEND IS WITHELD DUE TO NON PROVISION OF VALID IBAN AND CNIC NAME OF TOTAL FOLIO NO. SHAREHOLDER ADDRESS SHARES NET DIVIDEND IBAN CNIC DIVIDEND STATUS PAKISTAN NATIONAL SHIPPING P.N.S.C. BUILDING, MOULVI TAMIZUDDIN KHAN ROAD, P.O. Witheld Due to non provision of valid 2 CORPORATION. BOX NO.5350 KARACHI. 6930 441787 IBAN and CNIC MR. MUHAMMED Witheld Due to non provision of valid 9 SWALEH B-160,BLOCK "A", NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI 180 10755 IBAN and CNIC C-26,DAWOOD CO.OP.HOUSING SOCI BESIDES T.V. STATION, Witheld Due to non provision of valid 13 MR. ALTAF GULMOHD NATIONAL STADIUM ROAD KARACHI 100 5975 IBAN and CNIC A-30,BLOCK 10-A EVACUEE TRUST SOCIETY GULSHAN-E- Witheld Due to non provision of valid 26 MRS. SHABANA ANJUM IQBAL, RASHID MINHAS ROAD,KARACHI 260 15535 4220187494324 IBAN MR. SH.BASHIR AHMED SUPERINTENDENT, LAHORE DRAINAGE CIRCLE, CANAL Witheld Due to non provision of valid 31 RATRAH BANK MOGHULPURA, LAHORE 130 7767 IBAN and CNIC MR. YUSUF ULLAH Witheld Due to non provision of valid 32 HUSSAIN. C/O. G. MOHIUDDIN, 5/95, KHURSHID ALAM ROAD, LAHORE 130 7767 IBAN and CNIC Witheld Due to non provision of valid 34 MR. MOHYUDDIN MALIK. C/O DR. MOHYUDDIN MALIK A.I.M. HOSPITAL SIALKOT 60 3600 IBAN and CNIC MR. MOHD RAFIQUE Witheld Due to non provision of valid 38 SHAHID BUTT. 111/G, 5/7 NAZIMABAD KARACHI-74600 400 24000 4210183852119 IBAN NATIONAL INVESTMENT TRUST LTD. 6TH FLOOR, NATIONAL Witheld Due to non provision of valid 39 MR. -

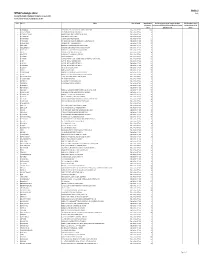

Of 39 in Case of Rural Number of Voters Assigned to Polling S.No No.And Name of Polling Station in Case of Urban Area S

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN FROM-28 (See rule 50) LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY Election to the *National Assembly No. and name of constituency NA-249 Karachi West- II In case of rural Number of voters assigned to polling S.No No.and Name of Polling Station In case of urban area S. no of voters on Number of polling booths areas the electoral roll in station Name of Census Block case electoral area Name of electoral area Male Female Total Male Female Total electoral area Code is bifurcated 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Islam Nagar 408010101 773 773 Islam Nagar Q 2 2 Babul Islam Sec School 1 Islam Nagar 408010102 378 378 3 0 3 (Male) Islam Nagar 408010108 240 240 1393 0 1393 Islam Nagar 408010103 234 234 Islam Nagar 408010104 258 258 Islam Nagar 408010105 101 101 Babul Islam Sec School 2 Islam Nagar 408010106 176 176 3 0 3 (Male) Islam Nagar 408010107 437 437 Islam Nagar 408010109 172 172 1378 0 1378 Islam Nagar 408010101 0 494 494 Islam Nagar Q 2 2 Islam Nagar 408010102 229 229 Islam Nagar 408010103 165 165 Islam Nagar 408010104 172 172 Babul Ilam Sec School 3 Islam Nagar 408010105 70 70 0 4 4 (Female) Islam Nagar 408010106 115 115 Islam Nagar 408010107 229 229 Islam Nagar 408010108 96 96 Islam Nagar 408010109 111 111 0 1683 1683 Abidabad Bl-A Islam Nagar 408010201 516 345 861 GBPS Siddiqui Abidabad Abidabad Bl-A Islam Nagar 408010202 354 193 547 4 2 1 3 (Combined) Abidabad Bl-A Islam Nagar 408010206 311 229 540 1181 767 1948 Abidabad Bl-A Islam Nagar 408010203 83 69 152 GBPS Siddiqui Abidabad Abidabad Bl-A Islam Nagar 408010204 497 341 838 5 2 1 3 (Combined) Abidabad Bl-A Islam Nagar 408010205 582 363 945 1162 773 1935 Page 1 of 39 In case of rural Number of voters assigned to polling S.No No.and Name of Polling Station In case of urban area S. -

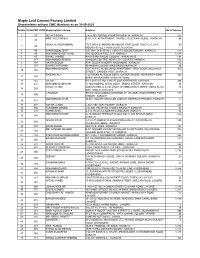

Mlcf List of Shareholders As 30-09-2020 (Without CNIC)

Maple Leaf Cement Factory Limited Shareholders without CNIC Numbers as on 30-09-2020 Sr.No. Folio/CDC A/C# Share-holder's Name Address No of Shares 1 33 NIGHAT BANO L-428 SECTOR NO.4 NORTH KARACHI KARACHI 512 MRS. KULSUM BAI B-10, U.K. APPARTMENT, PHASE-I, GULSHAN-I-IQBAL, KARACHI. 44 2 35 AISHA ALI MOHAMMAD FLAT NO.4-B, MADINA MANSION, 4TH FLOOR, PLOT G.K. 2/14, 90 3 44 MOOSA STREET, KHARADAR, KARACHI. 4 49 ZAFER IQBAL BATT J.M 138/139 B-303 M.L HEIGHTS SOLDIER BAZAR KARACHI 110 5 84 MUHAMMAD ASIF KHAN 19/C BLOCK-6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI 1,188 6 85 SHAKIL AHMED 4/403 SHAH FAISAL COLONY KARACHI-25 196 7 117 MOHAMMAD ARSHID 19-HOOR CENTRE, NEAR CITY COURTS, KARACHI. 132 8 134 HAJRA BEGUM A541 BLOCK N NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 132 9 137 SHAHID YAR KHAN 46-HASAN COLONY, NAZIMABAD, KARACHI. 44 MOHAMMAD IQBAL FLAT # A-15, AL-MUJAHID APARTMENT, 3RD FLOOR, MILLWALA 360 10 155 STREET, GARDEN WEST, KARACHI RAMZAN ALI C/O HASAN ALI BOOK DEPO, QASIER ZAINAB, NEAR BARA IMAM 148 11 234 BARA, KHARADHAR, KARACHI-74000. 12 244 NAJMA BR 1/40 FLAT NO.3 2ND FLOOR KHARADAR KARACHI 396 13 274 MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM 17-MOHAMMAD AFZAL BLDG. JINNAH STREET KARACHI 44 KANIZ FATIMA USMAN AHMED & CO. DADA CHAMBERS M.A JINNAH ROAD NEAR 16 14 285 M/W TOWER KARACHI A RAZZAK SR 9/43 MOHAMMADI MANSION 4TH FLOOR J.RAM STREET PAK 148 15 304 CHOWK KARACHI MOHAMMAD AYUB 92-B/II, SOUTH CIRCULAR AVENUE, DEFENCE, PHASE-II, KARACHI. -

Housing 2006 DAP-NEDUET

ARCHIVES Housing 2006 DAP-NEDUET NEWSPAPER CLIPPING Author New Paper News Paper Agency Title Type Date Page No. Name Page No. Last First Jabbar Rubina Made homeless and out in the cold Article The News 42 15-Jan-06 1 Haque Ihtasham ul Proposal to check housing fraud Article Daily Dawn 3 24-Jan-06 2 Tanoli Qadeer Hussain Delhi Colony: an Island of relative calm Article The News 4 12-Feb-06 3 Yusufzai Ashfaq Environment problem linked to expansion of refugee settlement Article Daily Dawn 4 16-Mar-06 4 Sharif Azizullah Protest against demolition of apartment in Bahadurabad Article Daily Dawn 17 16-Mar-06 5 Rashdi Maheen A. Urbanization increasing class disparity Article Daily Dawn 19 28-Mar-06 6 Ahmed Dr Noman Housing options for the poor Article Daily Dawn EB iv 1-May-06 7 Haque Ihtasham ul Wage increase, of land proposed Article Daily Dawn 16 10-May-06 8 Baloch Latif New lease rates for katchi abadis proposed Article Daily Dawn 17,19 1-Jun-06 9 Baloch Latif City Council approves new lease rates for katchi abadis Article Daily Dawn 17 2-Jun-06 10 Pathan Adeel 9/7 makes thousands homeless in 18 hours Article Daily Dawn 42 17-Sep-06 11 Zafar Imran Making house-building affordable Article Daily Dawn EB V 2-Oct-06 12 Baloch Latif Lyari facing housing shortage Article Daily Dawn 19 15-Oct-06 13 Ahmed Dr Noman Housing problems of low income groups Article Daily Dawn EB v 16-Oct-06 14 Khan Shujaat Ali KBCA told to raze 3 bungalows in Clifton Article Daily Dawn 17 18-Oct-06 15 Ahmed Shakeel Illegal` houses razed in Khanewal Article Daily Dawn 5 -

Allianz Efu Health Protector

Branch Network Sindh Maatli G.T. Road Chakdara Karachi Mehar Kacheri Chowk Chitral Abul Hasan Isphani Road Mirpur Khas D.I. Khan Bahadurabad Mithi Kasur Dara Adam Khel (FR Kohat) Boat Basin Moro Agrow Kasur Haripur Bohra Pir Naushehro Feroz Kasur Mansehra Allianz EFU - Health Protector Chase Shaheed-e-Millat Nawabshah Pakpattan Mardan Clifton Block 2 Pano Aqil Agrow Pakpattan Matani Changan Cloth Market Sanghar Pakpattan Mingora Delhi Colony Sehwan Shareef Nowshera DHA 26th Street Shahdadkot Sahiwal Saleh Khana DHA Khadda Market Shahdadpur Chak 89 Dist. Sahiwal Shaidu (NWFP), Nowshera DHA Kh-e-Bokhari Sheikh Bhirkio Sahiwal Shakas DHA Kh-e-Ittehad Shikarpur Sialkot Timergara DHA Kh-e-Shahbaz Sultanabad Paris Road Topi DHA Korangi Road Phase I Tando Adam Shahabpura Upper Dir DHA Phase 8 Tando Allah Yaar Sialkot Cantt DHA Zamzama Tando Jam Balochistan Dhoraji Tando Muhammad Khan Sheikhupura Quetta Electronic Market Thatta Agrow Sheikhupura M.A. Jinnah Road F.B. Area Umer Kot Sheikhupura Quetta Cantt Fisheries Zarghoon Road Punjab Agrow Allahabad Theeng Morr Garden East Dera Murad Jamali Garden West Lahore Agrow Chishtian Allama Iqbal Town Agrow Warburton Dukki Gulistan-e-Jauhar Gwadar Gulshan Chowrangi Azam Cloth Market Alipur Chatta Badami Bagh Arifwala Khanozai Gulshan-e-Hadeed Khuzdar Gulshan-e-Iqbal Baghbanpura Attock Bahria Town Bahawalpur Loralai Hawksbay Road Muslim Bagh Hyderi Market Brandreth Road Bhakkar Cavalry Ground Bhalwal Ormara IBA City Campus Usta Muhammad Islamia College Chowburji Bahawalnagar Jheel Park Circular Road Burewala Azad Jammu & Jodia Bazar College Road Chah Chand Wala Jampur Kashmir Karachi Stock Exchange Building Daroughawala, Lahore Chakwal Bagh Korangi Industrial Area DHA Airport Road Chichawatni Chaksawari Landhi DHA Phase VI Chiniot Charhoi Lucky Star DHA T-Block Daska Dadyal M.A. -

Survey of Pakistan

SURVEY OF PAKISTAN BID SOLICITATION DOCUMENT FOR AWARD OF CONTRACT OF CADASTRAL MAPPING OF KARACHI CITY (ZONE-A) Survey of Pakistan, Faizabad, Murree Road, Rawalpindi Table of Contents 1. Project Overview ............................................................................................... 3 2. Request For Proposal ......................................................................................... 3 2.1 Validity Of The Proposal / Bid ............................................................................. 3 2.2 Brief Description Of The Selection Process ........................................................ 3 2.3 Bid Security ......................................................................................................... 4 2.4 Schedule Of Selection Process ........................................................................... 4 2.5 Pre-Bid Conference ............................................................................................. 4 3. Instructions To The Prospective Bidders ....................................................... 5 4. Data Sheet ....................................................................................................... 10 5. Bid Proposals .................................................................................................. 13 6. Financial Proposal / Bid ................................................................................. 15 7. Evaluation Process ........................................................................................ -

%Otcti Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 Mitlibries Email: [email protected] Document Services

THE "PRESENT" OF THE PAST: Persistence of Ethnicity in Built Form by KHADIJA JAMAL Bachelor of Architecture NED University of Engineering and Technology Karachi, Pakistan January 1986 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1989 @ Khadija Jamal 1989 All rights reserved The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of author Khadija Jamal Department of Architecture May 12, 1989 Certified by Ronald B. Lewcock Professor of Architecture and Aga Khan Professor of Design for Islamic Societies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by IJ \,j Julian Beinart Chairman, Department Committee for Graduate Students nASSA~IUSETTS INSTiUM OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 0 2 1989 UBMC %otcti Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. The images contained in this document are of the best quality available. THE "PRESENT" OF THE PAST: Persistence of Ethnicity In Built Form by KHADIJA JAMAL Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 12, 1989 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis was generated by the prevailing social situation in the city of Karachi, where many communities and ethnic groups co-exist in ethnically defined areas. -

WEB OPEN Branches 04 May 2020.Xlsx

Branch Code Name Adress City/Town 9113 Korangi Rd DHA Phase I Karachi World Business Center 147, Main Korangi Road,DHA Phase 1, Karachi. Karachi 9109 Kh-e-Bokhari DHA Phase VI Karachi 18-C, Khayaban-e-Bukhari, DHA Phase VI, Karachi Karachi 9526 Islamia College Karachi Showroom # 3,Ashfaq Plaza, Commercial Plot # J.M.714/5, Jamshed Quarter M A Jinnah Road Karachi 9520 Kh-e-Shahbaz DHA Phase VI Karachi Rahimtoola Building,38-C, Khayaban-E-Shahbaz Phase-6, Dha Karachi Karachi 9617 North Karachi Ind Area Karachi KYC SA-3 Sector 12-B,North Karachi Township.North Karachi Industrial Area, Karachi Karachi 9089 IBA City Campus Karachi IBA City Campus ,Garden Kiyani Road, Karachi Karachi 9004 Park Towers Clifton Karachi Park Tower, Shahrah-E-Iran, Karachi Karachi 9501 Gulshan-e-Iqbal Karachi Shop No. 8 & 9, SB-42, Block No. 13-B, Main University Road, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi. Karachi 9029 Hawksbay Road Karachi (RUA) Plot # 637 A, New Quaid-e-Azam, Truck Stand, HawksBay Road Gate # 3, (Showroom PAK MEMON TRANSPORT COMPANY) Karachi 9528 Lucky Star Karachi Malik Manzil, Plot # 73, Survey Sheet # Sb-3, Saddar Bazar Quarter Karachi 9519 Jheel Park Karachi 831-C, Block-2, Pechs-Karachi Karachi 9522 Dhorajee Karachi Plot # 354, Survery Sheet # 35-P/1, Block-7 & 8, Dhorahjee Karachi 9512 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi Plot# 27-28 Sector# 16, Showroom #9 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 9509 North Nazimabad Karachi - (New Premises) Plot # SB-60, Block K, Ground Floor, North Nazimabad, Karachi Karachi 9040 Jodia Bazar Karachi G-1, G-2 & G-4, BHAGWANDAS BUILDING, PLOT # MR-4/9, D.S.II-B-166,MARKET QUARTERS, ACHEE QABAR,JODIA BAZAAR.KARACHI Karachi 9007 SITE Karachi Plot# B-53 B Site-Karachi Karachi 9621 26th Street DHA Phase V Karachi 16 C, Main 26th Street DHA Main Tauheed Commercial Area, Next to Biryani Centre DHA Karachi Karachi 9514 Zamzama Karachi F-10, Zam-1 Zamzama Boulevard Phase V, D.H.A-Karachi Karachi 9099 Progressive Centre Sh-e-Faisal Karachi (Shop-8-9) Show Room No. -

Bus Routes Karachi January 2010

Bus Routes Karachi January 2010 Route #: 1-A Stops: Faqir Colony, Metroville, Bawany Ghali, Valika Mill, Habbib Bank, Petrol Pump, Lasbela, Sabilwali Masjid, Old Exhibition, Sadar, Frere Road, Burns Road, Bandar Road, Tower Route #: 1-B Stops: Nazimabd, Bara Maidan, Lasbela, Lawrence Road, Barness Street, Bandar Road, Tower Route #: 1-C Stops: M.P.R Colony, Qasba Colony, Banaras Colony, Pathan Colony, S.I.T.E, Habib Bank, Bismillah Hotel, Gandhi Garden, Garden Road, Plaza, Regal, Shahra-e-Liaquat, National Museum, Tower, Sultanabad Route #: 1-D Stops: Ittehad Town, Torri Chowk Sector II, Orangi Township, Banaras Colony, Pathan Colony, Petrol Pump, Liaquatabad No. 10, Liaquatabad, Post Office, Teen Hatti, Jehangir Road, Empress Market, Cantt Station Route #: 1-F Stops: Naval Colony, Mauripur, Gulbai Chowk, Tower, Juna Market, Ramswami, Garden Bara Board, Valika, Orangi Township No. 10 Route #: 1-G Stops: M.W Tower, Frere Road, Sadar, Numaish, Goro Mandir, Teen Hatti, Liaquat No. 10, Petrol Pump, Nazimabad No. 2, Gandhi Chowk, Paposh Nagar, Abdullah College, Metro Cinema, Data Chowk Orangi Town Route #: 1-H Stops: Gulshan-e-Bahar, Orangi Sector No. 14, Orangi Sector No. 13, Orangi Sector No. 7, Orangi Sector No. 5, Qadafi Chowk, Qasba Mour, Banaras Colony, Valika Hospital, Valika Mill, Habib Bank, S.I.T.E, Post Office, Maroon Mill, Laltain Factory, Ghani Chowk, Shershah, Miran Naka, Chakiwara, Lee Market, Kharadar, Jamat Khana, Tower Route #: 1-K Stops: Tower, Regal Cinema, Plaza, Garden, Pakistan Quarters, Bara Board, Banaras, Qasba Mour, -

Detail of Unclaimed Dividend As at 30-06-2020

Annexure - A NETSOL Technologies Limited (Part-I) Investor Wise Details of Unclaimed Dividend as at June 30, 2020. For the Period From June 30, 2008 to June 30, 2017 Sr No Name (s) Address Nature of Amount Amount to which Due Date for transfer into the Companies Unclaimed Other Information as may be each person is Instruments and Dividend and Insurance Benefits and Investor considered relevant for the entitled Education Account purpose 1 MR. IRFAN MUSTAFA 233- WIL SHINE BULEVARD,, SUITE NO.930, SANTA MONIKA, CALIFORNIA 90401. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 109,981 2 MR. SHAHID JAVED BURKI 11112 STACKHOUSE CT POTOMAC,, MD 20854, U.S.A. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 81 3 MR. EDWARD ALLEN HOLMES HOMINGTON DOWN, SALISBURY,, WILTSHIRE, ENGLAND, SP5 4NW Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 757 4 MR. EUGEN BECKERT GUNDEITWEG, 1075365 CALW,, GERMANY. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 757 5 MR, NISHAT HUSSAIN C-5 SHADAB COLONY, TIMPLE ROAD LAHORE. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 547 6 MR. OWAIS QASSIM 67/3, KARACHI MEMON,, CO.OPERATIVE HOUSING SOCIETY, ALAMGIR ROAD, KARACHI. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 547 7 MR. WALEED FAROOQ 638-W BLOCK PHAS 111,, D.H.A, LAHORE PAKISTAN. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 547 8 SHAHID HAMEED HOUSE NO 210 7/10 MANWABAD, NEAR MADINA MASJID NAWABSHAH Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 71 9 SHAKEEL AHMED MALIK BUDHAL SHAH COLONY NEAR, MADINA MASJID MANWABAD NAWABSHAH. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 71 10 NIAMAT-UL-LAH HOUSE NO 153-TAJ COLONY, NEAR GIRLS SCHOOL NAWAB SHAH. Final Cash Dividend "FY-2008" 71 11 UZMA ADIL C/O MAJOR ADIL 89 ORDANACE UNIT, SIALKOT CANTT. -

WEB OPEN Branches 29APR2022.Xlsx

Branch Code Name Adress City/Town 9113 Korangi Rd DHA Phase I Karachi World Business Center 147, Main Korangi Road,DHA Phase 1, Karachi. Karachi 9109 Kh-e-Bokhari DHA Phase VI Karachi 18-C, Khayaban-e-Bukhari, DHA Phase VI, Karachi Karachi 9526 Islamia College Karachi Showroom # 3,Ashfaq Plaza, Commercial Plot # J.M.714/5, Jamshed Quarter M A Jinnah Road Karachi 9520 Kh-e-Shahbaz DHA Phase VI Karachi Rahimtoola Building,38-C, Khayaban-E-Shahbaz Phase-6, Dha Karachi Karachi 9617 North Karachi Ind Area Karachi KYC SA-3 Sector 12-B,North Karachi Township.North Karachi Industrial Area, Karachi Karachi 9089 IBA City Campus Karachi IBA City Campus ,Garden Kiyani Road, Karachi Karachi 9004 Park Towers Clifton Karachi Park Tower, Shahrah-E-Iran, Karachi Karachi 9501 Gulshan-e-Iqbal Karachi Shop No. 8 & 9, SB-42, Block No. 13-B, Main University Road, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi. Karachi 9029 Hawksbay Road Karachi (RUA) Plot # 637 A, New Quaid-e-Azam, Truck Stand, HawksBay Road Gate # 3, (Showroom PAK MEMON TRANSPORT COMPANY) Karachi 9528 Lucky Star Karachi Malik Manzil, Plot # 73, Survey Sheet # Sb-3, Saddar Bazar Quarter Karachi 9519 Jheel Park Karachi 831-C, Block-2, Pechs-Karachi Karachi 9522 Dhorajee Karachi Plot # 354, Survery Sheet # 35-P/1, Block-7 & 8, Dhorahjee Karachi 9512 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi Plot# 27-28 Sector# 16, Showroom #9 Korangi Industrial Area Karachi 9509 North Nazimabad Karachi - (New Premises) Plot # SB-60, Block K, Ground Floor, North Nazimabad, Karachi Karachi 9040 Jodia Bazar Karachi G-1, G-2 & G-4, BHAGWANDAS BUILDING, PLOT # MR-4/9, D.S.II-B-166,MARKET QUARTERS, ACHEE QABAR,JODIA BAZAAR.KARACHI Karachi 9007 SITE Karachi Plot# B-53 B Site-Karachi Karachi 9621 26th Street DHA Phase V Karachi 16 C, Main 26th Street DHA Main Tauheed Commercial Area, Next to Biryani Centre DHA Karachi Karachi 9514 Zamzama Karachi F-10, Zam-1 Zamzama Boulevard Phase V, D.H.A-Karachi Karachi 9099 Progressive Centre Sh-e-Faisal Karachi (Shop-8-9) Show Room No.