A Comparison of Samuel Barber's Knoxville: Summer of 1915 And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

PACO158 Front.Std

[ill □§@ Pristine □ □ Pristine DIGITAL AUDIO PACO 158 Puccini XR XR Manon Lescaut PACO 158 Giacomo Puccini's third opera, Manon Lescaut, premiered at the Teatro Regio, Turin in 1893 and was the first of his operas to garner I I international acclaim. Musically the opera showed clear evidence of Puccini's growing mastery of tuneful lyricism and his ability to Rn~~t~u~ n evoke a sense of place. The story of a doomed heroine was one that Puccini would return to with even greater success in La Bohf?me (1896), Tosca (1900) and Madama Butterfly (1904). The New York premiere in 1907 featured Lina Cavalieri, Enrico Caruso and Antonio Scotti in the cast, and Puccini himself in the audience, but fell out of the repertoire in between 1929 and 1949. When a new Met production of Manon Lescaut was mounted in 1949 it featured Swedish t enor Jussi Bjbrllng as Des Grieux. Bjbrling learned only two new roles after branching out from his operatic home at the Royal Swedish Opera in the lat e 1930s. One was Don manon licia albanese Carlo, which opened Rudolf Bing's tenure as general manager of the Metropolitan Opera in November 1950, the other was Des Grieux in Manon Lescaut. Over ten years, between 1949 and 1959, Bjbrling sang the role just 25 times, but we have no less than four des grieux Jussi bjbrling complete recordings of him in this opera: the Met's first ever broadcast of the opera in 1949, a studio recording in 1954, this Met broadcast from 1956, and a bi-lingual broadcast from Stockholm in 1959. -

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

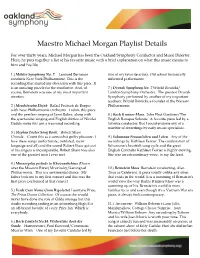

Michael Morgan Playlist

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

1718Studyguidetosca.Pdf

TOSCA An opera in three acts by Giocomo Puccini Text by Giacosa and Illica after the play by Sardou Premiere on January 14, 1900, at the Teatro Constanzi, Rome OCTOBER 5 & 7, 2O17 Andrew Jackson Hall, TPAC The Patricia and Rodes Hart Production Directed by John Hoomes Conducted by Dean Williamson Featuring the Nashville Opera Orchestra CAST & CHARACTERS Floria Tosca, a celebrated singer Jennifer Rowley* Mario Cavaradossi, a painter John Pickle* Baron Scarpia, chief of police Weston Hurt* Cesare Angelotti, a political prisoner Jeffrey Williams† Sacristan/Jailer Rafael Porto* Sciarrone, a gendarme Mark Whatley† Spoletta, a police agent Thomas Leighton* * Nashville Opera debut † Former Mary Ragland Young Artist TICKETS & INFORMATION Contact Nashville Opera at 615.832.5242 or visit nashvilleopera.org. Study Guide Contributors Anna Young, Education Director Cara Schneider, Creative Director THE STORY SETTING: Rome, 1800 ACT I - The church of Sant’Andrea della Valle quickly helps to conceal Angelotti once more. Tosca is immediately suspicious and accuses Cavaradossi of A political prisoner, Cesare Angelotti, has just escaped and being unfaithful, having heard a conversation cease as she seeks refuge in the church, Sant’Andrea della Valle. His sis - entered. After seeing the portrait, she notices the similari - ter, the Marchesa Attavanti, has often prayed for his release ties between the depiction of Mary Magdalene and the in the very same chapel. During these visits, she has been blonde hair and blue eyes of the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca, observed by Mario Cavaradossi, the painter. Cavaradossi who is often unreasonably jealous, feels her fears are con - has been working on a portrait of Mary Magdalene and the firmed at the sight of the painting. -

A Unique Opportunity to Learn and Perform a Complete Opera Role In

TUITION: FREE!! While tuition is free, housing and living expenses are the responsibility of the participants. Information about housing for participants from outside New York City will be available. APPLICATION You may download an application from our web site: www.martinaarroyofdn.org La Rondine La Rondine THE MISSION STATEMENT The Mission of The Martina Arroyo Founda- tion is to prepare and counsel young singers in the interpretation of complete operatic roles for public performance. The Foundation guides each singer in the preparation of an entire operatic role through a formal educational process that includes the background of the drama, the historical per- spective, the psychological motivation of each character, and language proficiency. A unique opportunity to Martina Arroyo Foundation, Inc. learn and perform The Martina Arroyo Foundation, Inc. is a tax-exempt, nonprofit organization under Sec. 501 (c) (3) of the Inter- a nal Revenue Code. Complete Opera Role ——————————————————————- in The Martina Arroyo Foundation, Inc. Martina Arroyo, President and Artistic Director New York City P.O. Box 2015 Radio City Station, NY, NY 10101 Tel: 212-315-9190 Fax: 212-397-7257 June 4 to July 16, 2012 Email: [email protected] Web: www.martinaarroyofdn.org Production Photos by Jen Joyce Davis Staff: PRELUDE TO PERFORMANCE PROGRAM OUTLINE Martina Arroyo Artistic Director and Role Class Prelude to Performance is a professional training program The first four weeks will be dedicated to sessions, staging, Mark Rucker Administrative Director for select young singers to experience role preparation individual coaching, masterclasses with professionals like Willie A. Waters Music Director guided by a team of opera professionals. -

Barber Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor, Opus 26

Barber Piano Sonata In E-flat Minor, Opus 26 Comparative Survey: 29 performances evaluated, September 2014 Samuel Barber (1910 - 1981) is most famous for his Adagio for Strings which achieved iconic status when it was played at F.D.R’s funeral procession and at subsequent solemn occasions of state. But he also wrote many wonderful songs, a symphony, a dramatic Sonata for Cello and Piano, and much more. He also contributed one of the most important 20th Century works written for the piano: The Piano Sonata, Op. 26. Written between 1947 and 1949, Barber’s Sonata vies, in terms of popularity, with Copland’s Piano Variations as one of the most frequently programmed and recorded works by an American composer. Despite snide remarks from Barber’s terminally insular academic contemporaries, the Sonata has been well received by audiences ever since its first flamboyant premier by Vladimir Horowitz. Barber’s unique brand of mid-20th Century post-romantic modernism is in full creative flower here with four well-contrasted movements that offer a full range of textures and techniques. Each of the strongly characterized movements offers a corresponding range of moods from jagged defiance, wistful nostalgia and dark despondency, to self-generating optimism, all of which is generously wrapped with Barber’s own soaring lyricism. The first movement, Allegro energico, is tough and angular, the most ‘modern’ of the movements in terms of aggressive dissonance. Yet it is not unremittingly pugilistic, for Barber provides the listener with alternating sections of dreamy introspection and moments of expansive optimism. The opening theme is stern and severe with jagged and dotted rhythms that give a sense of propelling physicality of gesture and a mood of angry defiance. -

A Formal Analytical Approach Was Utilized to Develop Chart Analyses Of

^ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 970 24 HE 000 764 .By-Hanson, John R. Form in Selected Twentieth-Century Piano Concertos. Final Report. Carroll Coll., Waukesha, Wis. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureauof Research. Bureau No-BR-7-E-157 Pub Date Nov 68 Crant OEC -0 -8 -000157-1803(010) Note-60p. EDRS Price tvw-s,ctso HC-$3.10 Descriptors-Charts, Educational Facilities, *Higher Education, *Music,*Music Techniques, Research A formal analytical approach was utilized to developchart analyses of all movements within 33 selected piano concertoscomposed in the twentieth century. The macroform, or overall structure, of each movement wasdetermined by the initial statement, frequency of use, andorder of each main thematic elementidentified. Theme groupings were then classified underformal classical prototypes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (ternary,sonata-allegro, 5-part or 7-part rondo, theme and variations, and others), modified versionsof these forms (three-part design), or a variety of free sectionalforms. The chart and thematic illustrations are followed by a commentary discussing each movement aswell as the entire concerto. No correlation exists between styles andforms of the 33 concertos--the 26 composers usetraditional,individualistic,classical,and dissonant formsina combination of ways. Almost all works contain commonunifying thematic elements, and cyclicism (identical theme occurring in more than1 movement) is used to a great degree. None of the movements in sonata-allegroform contain double expositions, but 22 concertos have 3 movements, and21 have cadenzas, suggesting that the composers havelargely respected standards established in theClassical-Romantic period. Appendix A is the complete form diagramof Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Appendix B has concentrated analyses of all the concertos,and Appendix C lists each movement accordog to its design.(WM) DE:802 FINAL REPORT Project No. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards.