SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE Feasibility Study REPORT 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Spatial Development Framework Review 2015

District Spatial Development Framework Review 2015 2015 DIRECTORATE: INTEGRATED PLANNING & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT JULY 2015 Contact: The Town Planner 045 – 807 4800 Private Bag X7121 QUEENSTOWN, 5230 Copies of this Document can be obtained from: The Municipal Manager Chris Hani District Municipality Private Bag X7121 QUEENSTOWN 5320 Contact: The Director: Integrated Planning & Economic Development Telephone: (045) 807 4800 Copyright Reserved © Permission to reproduce the contents of this document must be obtained from the Chris Hani District Municipality. CHRIS HANI DISTRICT SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK REVIEW JULY 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE OF CHRIS HANI DISTRICT INTRODUCTION The points below set out some of the most distinctive features of the Chris Hani District taken into consideration in the review of the SDF: - In accordance with the requirements of legislation governing municipal planning, the Chris Hani District Municipality (CHDM) reviewed its District Spatial Development Framework (SDF). • It is estimated that the total population of the district in 2015 will reach about 813,473 people (approximately 216,600 households), with the highest population densities located in the former Ciskei and In line with the function of the District Municipality to co-ordinate development activities in the district, the District Transkei areas. This reflects a reduction from previous estimates (2001 and 2004) and suggests that the SDF should be taken as a guide to where planning and development initiatives could best be directed -

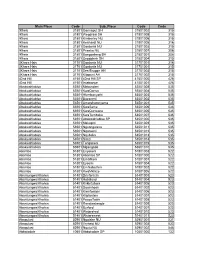

Mainplace Codelist.Xls

Main Place Code Sub_Place Code Code !Kheis 31801 Gannaput SH 31801002 315 !Kheis 31801 Wegdraai SH 31801008 315 !Kheis 31801 Kimberley NU 31801006 315 !Kheis 31801 Kenhardt NU 31801005 316 !Kheis 31801 Gordonia NU 31801003 315 !Kheis 31801 Prieska NU 31801007 306 !Kheis 31801 Boegoeberg SH 31801001 306 !Kheis 31801 Grootdrink SH 31801004 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 316 ||Khara Hais 31701 Gordonia NU 31701001 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Ses-Brugge AH 31701003 315 ||Khara Hais 31701 Klippunt AH 31701002 315 42nd Hill 41501 42nd Hill SP 41501000 426 42nd Hill 41501 Intabazwe 41501001 426 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mabundeni 53501008 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQonsa 53501004 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Hlambanyathi 53501003 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Bazaneni 53501002 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Amatshamnyama 53501001 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaSeme 53501006 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaQunwane 53501005 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 KwaTembeka 53501007 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Abakwahlabisa SP 53501000 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Makopini 53501009 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Ngxongwana 53501011 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqotweni 53501012 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Nqubeka 53501013 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Sitezi 53501014 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Tanganeni 53501015 535 Abakwahlabisa 53501 Mgangado 53501010 535 Abambo 51801 Enyokeni 51801003 522 Abambo 51801 Abambo SP 51801000 522 Abambo 51801 Emafikeni 51801001 522 Abambo 51801 Eyosini 51801004 522 Abambo 51801 Emhlabathini 51801002 522 Abambo 51801 KwaMkhize 51801005 522 Abantungwa/Kholwa 51401 Driefontein 51401003 523 -

Eastern Cape No Fee Schools 2021

EASTERN CAPE NO FEE SCHOOLS 2021 NATIONAL NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER EMIS 2021 NUMBERS NUMBER 2021 200600003 AM ZANTSI SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY Manzimahle A/A,Cala,Cala,5455 CHRIS HANI EAST 1 583 200300003 AMABELE SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY Dyosini A/A,Ndabakazi,Ndabakazi,4962 AMATHOLE EAST 1 279 200300005 AMABHELENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL PRIMARY Candu Aa,Dutywa,5000 AMATHOLE EAST 1 154 200400006 AMAMBALU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL COMBINED Xorana Administrative Area,Mqanduli,5080 O R TAMBO INLAND 1 88 200300717 AMAMBALU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY Qombolo A/A,Centane,4980 AMATHOLE EAST 1 148 200600196 AMOS MLUNGWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY Erf 5252,Extension 15,Cala,5455 CHRIS HANI EAST 1 338 200300006 ANTA JUNIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY Msintsana A/A,Teko 'C',Centane,4980 AMATHOLE EAST 1 250 200500004 ANTIOCH PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY Nqalweni Aa,Mount Frere,5090 ALFRED NZO WEST 1 129 200500006 AZARIEL SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY AZARIEL LOCATION, P.O BOX 238, MATATIELE, 4730 ALFRED NZO WEST 1 520 200600021 B A MBAM JUNIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY Bankies Village,N/A,Lady Frere,5410 CHRIS HANI WEST 1 104 200600022 B B MDLEDLE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL COMBINED Askeaton A/A,Cala,5455 CHRIS HANI EAST 1 615 200300007 B SANDILE SENIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY Qombolo A/A,Nqileni Location,Kentani,4980 AMATHOLE EAST 1 188 200500007 BABANE SENIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY RAMZI A/A, PRIVATE BAG 505, FLAGSTAFF 4810, 4810 O R TAMBO COASTAL 1 276 200500008 BABHEKE SENIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape Permit Primary Name Address Number 202103960 Fonteine Park Apteek 115 Da Gama Rd, Ferreira Town, Jeffreys Bay Sarah Baartman DM Eastern Cape 202103949 Mqhele Clinic Mpakama, Mqhele Location Elliotdale Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103754 Masincedane Clinic Lukhanyisweni Location Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103840 ISUZU STRUANWAY OCCUPATIONAL N Mandela Bay MM CLINIC Eastern Cape 202103753 Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103725 Pricesdale Clinic Mbekweni Village Whittlesea C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103724 Lubisi Clinic Po Southeville A/A Lubisi C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103721 Eureka Clinic 1228 Angelier Street 9744 Joe Gqabi DM Eastern Cape 202103586 Bengu Clinic Bengu Lady Frere (Emalahleni) C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103588 ISUZU PENSIONERS KEMPSTON ROAD N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape 202103584 Mhlanga Clinic Mlhaya Cliwe St Augustine Jss C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103658 Westering Medicross 541 Cape Road, Linton Grange, Port Elizabeth N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103581 Tsengiwe Clinic Next To Tsengiwe J.P.S C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103571 Askeaton Clinic Next To B.B. Mdledle J.S.School Askeaton C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103433 Qitsi Clinic Mdibaniso Aa, Qitsi Cofimvaba C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103227 Punzana Clinic Tildin Lp School Tildin Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103186 Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Aa Libode O Tambo DM Eastern Cape 202103214 Lotana Clinic Next To Lotana Clinic Lotana -

Cradock Education District

YETO STATE AIDED SAMEKOMS P 33 WONDERBOOM FARM NOORDHOEK FARM DORRINGTON FARM R56 NOSIPHIWO FARM SMITSRIVIER FARM BROUGHTON FARM DALUVUYO P Khayamnandi Clinic STEYNSBURG COMBINED Steynsburg Mobile PAUL KRUGER COLLEGE Steynsburg UNIE P/LAER K L Steynsburg Hospital Steynsburg Clinic E I N - S NOOITGEDACHT P E E 1 K 1 Gariep Local Municipality O N9 COLLINGHAM E FRERE DELL FARM I R I V I E 22 R N10 CHAMISO FARM BOESMANSHOEK FARM TEEBUS Nceduluntu Clinic NOMONDE PUBLIC JOE SLOVO FREEDOM H NOLITHA P NCEBA PUBLIC Malethswai Local Municipality Nomonde Clinic Molteno Clinic MoltenoM Hoolstpeitnaol EDELWEISS PRIMARY MARSHMOOR FARM 1 Molteno Mobile MOLTENO H LEEUFONTEIN FARM 1 HILLSTON FARM 11 PENRYN FARM SCHOOMBEE P SCHOOMBEE TRUST P Schoombie ER VI RI US R391 EB COUNTRY VIEW TE Middelburg ROSMEAD P Wilhelm Stahl (Middelburg) Hospital ROSMEAD (D.R.C.) P MKAIDRDEELL TBHUERRGO HN P Middelburg Clinic Middelburg Mobile 3 Inkwanca Local Municipality Middelburg Mobi33le M21idros Clinic MIDDELLAND VAN DER MERWE MEMORIAL P ELLEN OLIVIER P 22 Kwanonzame Old Clinic ST BONIFACE PUBLIC P R KING GLEN FARM E I NONYANISO P V I R Kwanonzame New Clinic EKUPHUMLENI S S U B E E T Sterkstroom ELUTHUTHU SStteerrkkssttrroooom HColisnpicital MUaSsEaNkhAeT HCIli nPicUBLIC PRIMARY Sterkstroom Mobile SIYAPHAKAMA SS R398 JOHN VORSTER COMPREHENSIVE LESFONTEIN P MPUMELELO P NTLALO PUBLIC S ER RIVI BUS TEE R397 NORWOOD J FARM PHAKAMA HOFMEYR H Eluxolweni Clinic MZAMOMHLE P OSBERG FARM HOFMEYR DRC P Hofmeyr Mobile SONSKYN P THE WILLOWS P Hofmeyr Hofmeyr Clinic HOUW KUILEN FARM -

Eastern Cape

Eastern Cape Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300001 10250019 CESHIRE HOMES -34.00014 25.66647 GOMERY AVENUE SUMMERSTRAND NELSON MANDELA [PORT ELIZABETH] NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300001 10250064 MANCE KARATE CLUB -33.99779 25.5352 12 PHYLLIS ST MOUNT PLEASANT PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300001 10460089 TEMPORARY VOTING STATION (RIVERSIDE) -33.97946 25.41881 KRAGGA KAMMA RD RIVERSIDE/COLLEEN GLEN PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300001 10460090 ELUKHOLWENI FARM SCHOOL -34.01007 25.50643 SEAVIEW ROAD LOVEMORE PARK AREA PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300002 10250020 PORTUGUESE CLUB -33.99097 25.66183 7TH AVENUE SUMMERSTRAND PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300002 10251087 KINGS BEACH LIFE SAVERS CLUB -33.9727 25.64575 BEACH ROAD HUMEWOOD PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300002 10251098 ACVV CENTRE -33.98034 25.63165 1 HILTON CRESCENT FOREST HILL PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300003 10250086 BUFFELSFONTEIN OLD AGE HOME -33.98891 25.55408 17TH AVENUE WALMER PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300003 10250097 WALMER TOWN HALL -33.97758 25.58525 MAIN ROAD WALMER PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300003 10251100 GREENWOOD PRIMARY SCHOOL -33.96836 25.61084 PARK DRIVE CENTRAL PORT ELIZABETH NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300003 10251661 SETTLERS PARK PRIMARY SCHOOL -33.97462 25.60174 4TH AVENUE WALMER NELSON MANDELA [PORT ELIZABETH] NMA - Nelson Mandela Bay 29300004 10250031 TEMPORARY VOTING STATION -

Appendix 1 Water Requirements

DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS AND FORESTRY DIRECTORATE OF OPTIONS ANALYSIS LUKANJI REGIONAL WATER SUPPLY FEASIBILITY STUDY APPENDIX 1 WATER REQUIREMENTS SUBMITTED BY Ninham Shand (Pty) Ltd P O Box 1347 Cape Town 8000 Tel : 021 - 481 2400 Fax : 021 - 424 5588 e-mail : [email protected] FINAL January 2006 Title : Appendix 1 : Water Requirements Authors : V Jonker and R Blackhurst Project Name : Lukanji Regional Water Supply Feasibility Study DWAF Report No. : P WMA 12/S00/3008 Ninham Shand Report No. : 10676/3841 Status of Report : Final First Issue : January 2006 Final Issue : January 2006 Approved for the Study Team : …………………………………… M J SHAND Ninham Shand (Pty) Ltd DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS AND FORESTRY Directorate : Options Analysis Approved for the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry by : A D BROWN Chief Engineer : Options Analysis (South) (Project Manager) …………………………………… L S MABUDA Director WATER REQUIREMENTS i LUKANJI REGIONAL WATER SUPPLY FEASIBILITY STUDY WATER REQUIREMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION The Lukanji Regional Water Supply Feasibility Study, commissioned by the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF), commenced in March 2003. The main aim of the study is to review the findings of earlier studies and, taking cognisance of new developments and priorities that have been identified in the study area, to make a firm recommendation on the next augmentation scheme to be developed for the supply of water to the urban complexes of Queenstown and Sada/Whittlesea following the implementation of a suitable water demand management programme. In addition, proposed operating rules will be identified for the existing water supply schemes and the augmentation scheme to provide for the ecological component of the Reserve and the equitable distribution of water between rural domestic and urban water supplies, and irrigators. -

Gis Time Series Mapping of a Former South African Homeland

GIS TIME SERIES MAPPING OF A FORMER SOUTH AFRICAN HOMELAND By SALIH MOHAMED SIDAHMED ALI 214319954 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Technology in Cartography In the Faculty of Engineering At the Cape Peninsula University of Technology Supervisor: Mr. S. Motala Co-supervisor: Prof. R. Fox Bellville 2016 CPUT copyright information The dissertation/thesis may not be published either in part (in scholarly, scientific or technical journals), or as a whole (as a monograph), unless permission has been obtained from the University Declaration I, Salih Mohamed Sidahmed Ali, declare that the contents of this dissertation/thesis represent my own unaided work, and that the dissertation/thesis has not previously been submitted for academic examination towards any qualification. Furthermore, it represents my own opinions and not necessarily those of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Signed Date i Abstract This case study investigates the change in the geographical boundaries by creating a Spatio-temporal mapping of Ciskei (one of the so-called Bantustans or Homelands) during the period of Apartheid. It examines the reasons for its establishment, and what impact the apartheid land legislation had on the geographical boundaries of Ciskei. GIS technology was used in this study to create time series animation and Static map to display the spatial change of the Ciskei boundaries. This investigation was split into quantitative and qualitative assessments. The aim of the quantitative assessments was to determine the amount of the spatial change of the Ciskei geographic boundary. The qualitative methods was used to investigate the map viewer’s understanding of the amount of the information in the static and animated maps. -

Zero Fee Schools 2014

EASTERN CAPE NO FEE SCHOOLS 2014 NATIONAL NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER EMIS 2014 NUMBERS NUMBER 2014 200600003 A M ZANTSI SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Secondary GOOD HOPE LOCATION,NGXAKAXA A/A,IDUTYWA,5000 COFIMVABA 1 329 200300003 AMABELE SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Secondary DYOSINI A/A, NDABAKAZI, BUTTERWORTH, 4960 BUTTERWORTH 1 325 200300005 AMABHELENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined CANDU A/A, , DUTYWA, 5000 DUTYWA 1 140 200300717 AMAMBALU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined AMAMBALU A/A,QOMBOLO,4980 BUTTERWORTH 1 102 200400006 AMAMBALU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined XORANA ADMINISTRATIVE AREA, , MQANDULI, MTHATA 1 247 200300006 ANTA PJ SCHOOL Combined MSINTSANA LOC.,TEKO "C" A/A,KENTANI,4960 BUTTERWORTH 1 282 200500004 ANTIOCH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined NQALWENI AA, , MOUNT FRERE, 5090 MT FRERE 1 157 200500006 AZARIEL SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY AZARIEL LOCATION,P.O BOX 238,MATATIELE,4730 MALUTI 1 1244 200600021 B A MBAM JUNIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary BANKIES VILLAGE, , LADY FRERE, 5410 LADY FRERE 1 69 200600022 B B MDLEDLE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined ASKEATON A/A, , CALA, 5455 COFIMVABA 1 289 200300007 B SANDILE SENIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary QOMBOLO A/A,KENTANI,4980 BUTTERWORTH 1 147 200500007 BABANE SENIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary RAMZI A/A,PRIVATE BAG 505,FLAGSTAFF 4810,4810 LUSIKISIKI 1 274 200500008 BABHEKE SENIOR PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary BOMVINI A/A,LUSIKISIKI,4820 LIBODE 1 113 200400008 BACELA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined KWENXURA A/A, , MQANDULI, MTHATA 1 466 200400009 BAFAZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined ,BAFAZI A/A,ELLIOTDALE,5070 DUTYWA 1 517 200500009 BAGQOZINI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined ,MNCEBA A/A,TABANKULU,5130 LUSIKISIKI 1 208 200500010 BAKALENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined BOMVINI A/A,BOX 158,LUSIKISIKI,4820 LIBODE 1 272 200500012 BALENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Combined AMADIBA ADMIN. -

Government Notice No. 1133

I STAATSKOERANT, 5 DESEMBER 2007 No. 30524 3 DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION 5 December 2007 SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOOLS ACT, 1996 (ACT NO. 84 OF 1996) PUBLICATION OF LIST OF NO FEE SCHOOLS PER PROVINCE: DECLARING NO FEE SCHOOLS IN 2008 FOR ALL NINE PROVINCES I, Grace Naledi Mandisa Pandor, Minister of Education, after having considered the lists of schools identified by the Member of the Executive Council for Education in each province and having compared those lists with the requirements set out in the amended National Norms and Standards for School Funding, hereby, in accordance with section 39(10) of the South African Schools Act, 1996 (Act No. 84 of 1996), publish the list set out in the Schedule, per province, of schools that may not charge school fees. The schools identified in the Schedule may not charge school fees for the 2008 school year, subject to the provisions of section 39 of the South African Schools Act, 1996. Specific questions regarding schools identified in the Schedule should be addressed to the MECs for Education in the provinces, at the following addresses: Mr J Makgato Mr MC Mokitlane MEC: Education MEC: Education Eastern Cape Free State Private Bag X0032 PO Box 521 BlSHO BLOEMFONTEIN 5605 9300 Tel. 040 608 420213 Tel. 051 404 8411 Fax 0406084247 Fax 051 4048295 Mrs A Motshekga Mrs I Cronje MEC: Education MEC: Education Gauteng KwaZulu-Natal PO Box 7710 Private Bag X9044 JOHANNESBURG PIETERMARITZBURG 2000 3200 Tel. 011 355 0909 Tel. 033 355 2450 Fax 01 1 355 0542 Fax 0333940893 4 No. 30524 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 5 DECEMBER 2007 Dr PA Motsoaledi Mr MSA Masango MEC: Education MEC: Education Limpopo Mpumalanga Private Bag X9489 PO Box 301 1 POLOKWANE NELSPRUIT 0700 1200 Tel. -

Download [PDF, 236.81

Alphabetical list of Place names for coding Code Place name Code Place name 82420001 Aankoms 12110101 Albertinia 55120001 Aapieshoek 70610102 Alberton 54420001 Abakwa Cele 70610103 Albertsdal 53420001 Abashumi 70410004 Albertskroon 13210101 Abbotsdale 82520001 Albertsnek 21910001 Abbotsford 70410005 Albertsville 70410001 Abbotsford 32110101 Albertynshof 92120001 Abbotspoort/Dikgopeng 70510002 Aldara Park 50720001 Abebhuzi 30110101 Alexander Bay 54320001 Abejuti 70510003 Alexandra 23110101 Aberdeen 22210101 Alexandria 23130001 Aberdeen NU 92720002 Alexandria 25020024 Abetshawe AA 22230001 Alexandria NU 81710301 Ackerville Informal 51030001 Alfred NU 92720048 Acornhoek 24010180 Algoa Park 52120001 Acton Homes 31530001 Alheit 70710101 Actonville 24710101 Alice 61210201 Adamayview 22110101 Alicedale 54130001 Adams College 20210101 Aliwal-North 54130003 Adams Mission 20230001 Aliwal-North NU 92020001 Addney 25310102 All Saints 22810101 Addo 24310101 All Saints College 22310101 Adelaide 50710101 Allandale 22330001 Adelaide NU 91420002 Allandale 10210101 Adriaanse 40610101 Allanridge 81510201 Aerorand 24110101 Allanridge Transit Camp 70410002 Aeroton 24110102 Allanridge West 22710101 Aeroville 90530001 Alldays 50920001 Africa Top 82920001 Allemansdrift B 50230001 Afrika 82920002 Allemansdrift C 92820001 Aftoni 82920003 Allemansdrift D 71510101 Agavia 71810101 Allen Nek 30130001 Aggeneys 71010101 Allengrove 91420001 Agincourt 21510101 Aloevale 60810301 Agisanang 21910002 Alphandale 44510101 Air Force Base 21910003 Alphandale Informal 70510001 -

Appendices Amatole – Kei Internal Strategic Perspective

APPENDICES AMATOLE – KEI INTERNAL STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVE APPENDICES APPENDIX A REFERENCES AND DOCUMENTATION Appendix A1 References and Reports Appendix A2 Guidelines/References (Groundwater and Solid Waste Aspects) Appendix A3 A Selected List of Groundwater References APPENDIX B ISP RELATED INFORMATION Appendix B1 Rivers, Dams and Towns in the ISP Area Appendix B2 Water and Waste Water Treatment Works in the Amatole System Appendix B3 Solid Waste Disposal Sites Appendix B4 Groundwater Maps Appendix B4.1 Study Area and Topography Appendix B4.2 Aquifer Type Appendix B4.3 NGDB and DWAF Monitoring Sites Appendix B4.4 Groundwater Occurrence Appendix B4.5 Recharge to Groundwater Appendix B4.6 Aquifer Vulnerability Appendix B5 DWAF Raw Water Use Charges (2003-2004) Appendix B6 Controlled and Major Irrigation Schemes Appendix B7 Water Management Institutions Appendix B8 Municipalities Appendix B9 Possible Future Bulk Water Schemes Appendix B10 Major Dams Appendix B11 List of Flow Gauging Stations Appendix B12 Major Infrastructure and Transfer Schemes Appendix B13 Urban Water Use/Estimated Demand and Sources Appendix B14 General Authorisations (Surface/Groundwater) Appendix B15 Estuaries APPENDIX C STUDY AREA MAPS Appendix C1 Locality Map Appendix C2 District Municipalities Appendix C3 Former Ciskei/Transkei/RSA borders APPENDIX A REFERENCES AND DOCUMENTATION APPENDIX A1 REFERENCES AND REPORTS 1. Amatole District Municipality. October 2000. Water Services Development Plan. 2. Amatole Systems Consulting Engineers (NS & HKS). July 1994. Situation Analysis : Bulk Water Supply and Sanitation. Prepared on behalf of the Amatola Regional Services Council. 3. Amatole Systems Consulting Engineers (NS & HKS). April 1995. Amatole Water Resources System Analysis Phase 1. DWAF Report No. PR 000/00/1295.