Molecular Species Delimitation of a Symbiotic Fig-Pollinating Wasp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ficus Cf. Platypoda Port Jackson Fig Moraceae

Ficus cf. platypoda Port jackson fig Moraceae Forest Starr, Kim Starr, and Lloyd Loope United States Geological Survey--Biological Resources Division Haleakala Field Station, Maui, Hawai'i January, 2003 OVERVIEW There are no Ficus species native to Hawai'i. F. cf. platypoda is one of about 60 species of Ficus that is cultivated in Hawai'i (Wagner et al. 1999). About 39,000 F. cf. platypoda trees were planted in the state of Hawai'i during the 1920's and 1930's as a forestry tree (Skolmen 1960). On Maui, F.cf. platypoda were planted in plantations along the Hana Hwy. from Ha'iku to Hana and in Fleming Arboretum on West Maui. The pollinator wasp for F. cf. platypoda, Pleistondontes imperialis Saunders, was introduced to Hawai'i in 1922 (Wagner et al. 1999) to facilitate the spread of this tree species as each Ficus species needs a specific pollinating wasp in order to reproduce and spread (Ramirez 1970). As a result, F. cf. platypoda is reproducing sexually in Hawai'i today. It was first reported by Nagata (1995) under the name F. rubiginosa Desf as naturalized on O'ahu. It was then later reported as naturalized on both West and East Maui (Wagner et al. 1999, Oppenheimer and Bartlett 2000). Two other Ficus species that have had their associated pollinator wasps introduced are also spreading on Maui. These include F. microcarpa and F. macrophylla (Wagner et al. 1999, Oppenheimer and Bartlett 2000). All three species invade both disturbed and native ecosystems. F. cf. platypoda is capable of germinating in native host trees, such as koa (Acacia koa) and ohia (Metrosideros polymorpha), growing as epiphytes, sending down aerial roots, and eventually destroying the host tree. -

Zoologische Mededelingen

MINISTERIE VAN ONDERWIJS KUNSTEN EN WETENSCHAPPEN ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN DEEL XXXVIII, No. 19 18 november 1963 INDO-MALAYAN AND PAPUAN FIG WASPS (HYMENOPTERA, CHALCIDOIDEA) 2. THE GENUS PLEISTODONTES SAUNDERS (AGAONIDAE) by J. T. WIEBES Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie, Leiden Until now, the genus Pleistodontes Saunders is known from the Australian continent and from Lord Howe Island. Two species were introduced into the Hawaiian Islands. Samples of fig wasps from New Guinea and from the Solomon Islands were sent to me by Mr. E. J. H. Corner. They proved to consist of new species of Pleistodontes, which are described below. In addition, some new records of Australian species, mostly taken from the collection of the Ha• waiian Sugar Planters' Association ("H.S.P.A."), Honolulu, are given, and the type species of the genus is redescribed. The records and "descriptions" by Girault are not considered in the present paper, as the typical material is being studied by Mr. E. F. Riek. A discussion on the host records follows the descriptions of the species. Pleistodontes blandus spec. nov. Material. — Eight immature 9, 14 $, ex Ficus glandifera Summerh. (det. E. J. H. Corner), Solomon Is., leg. Kajewski, no. 3494; coll. Museum Leiden, no. 438; holotype, S, slide no. 438b, allotype, 9, slide 438a, paratypes, 9 $, slides 438c, d. Description. — Male. Head (fig. 10) distinctly longer than its maximum width, and nearly twice as long as wide anteriorly; with the usual pubescence next to the antennal groove and behind the hypostomal margin. Eyes large. Mandible, fig. -

Investigations Into Stability in the Fig/Fig-Wasp Mutualism

Investigations into stability in the fig/fig-wasp mutualism Sarah Al-Beidh A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Imperial College London. Declaration I hereby declare that this submission is my own work, or if not, it is clearly stated and fully acknowledged in the text. Sarah Al-Beidh 2 Abstract Fig trees (Ficus, Moraceae) and their pollinating wasps (Chalcidoidea, Agaonidae) are involved in an obligate mutualism where each partner relies on the other in order to reproduce: the pollinating fig wasps are a fig tree’s only pollen disperser whilst the fig trees provide the wasps with places in which to lay their eggs. Mutualistic interactions are, however, ultimately genetically selfish and as such, are often rife with conflict. Fig trees are either monoecious, where wasps and seeds develop together within fig fruit (syconia), or dioecious, where wasps and seeds develop separately. In interactions between monoecious fig trees and their pollinating wasps, there are conflicts of interest over the relative allocation of fig flowers to wasp and seed development. Although fig trees reap the rewards associated with wasp and seed production (through pollen and seed dispersal respectively), pollinators only benefit directly from flowers that nurture the development of wasp larvae, and increase their fitness by attempting to oviposit in as many ovules as possible. If successful, this oviposition strategy would eventually destroy the mutualism; however, the interaction has lasted for over 60 million years suggesting that mechanisms must be in place to limit wasp oviposition. This thesis addresses a number of factors to elucidate how stability may be achieved in monoecious fig systems. -

Evolution of Tbe Mandibular Appendage in Figwasps (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae)

Rev. Biol. Trop., 39 (1): 87-95. 1991 Evolution of tbe mandibular appendage in figwasps (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae) William Ramírez B. Escuela de Fitotecnia, Universidadde Costa Rica. (Ree. 20-IX-I990. Acep. 15-X-I990) Abstract: The phylogenetic value of the conformation of the mandibular appendages, the number of mandibular glands andother head characters in the Agaonidae are examined.The phylogenetic arrangement suggests thatthe pre agaonid had a normal bidentate mandible with two glands, and a undistinct facial groove as in sorneDiazi ella (Sycoecinae), Sycophaga (Sycophaginae) and in related chalcidoid non-pollinating fig wasps. lt also had thirteen-seg mented antennae;'a long scape, several times ¡onger than wide a long triangular pedicel, two or three anelli andeight flagellomeres withsensilla (as uniquely found in Tetrapus). The mandibularappendage apparently co-evolved with the development oí the ostiolum of thesyconium andthe firstmandibular appendage was fixed andhad ridges or lameUae. A flexible hinge evolved laterat its base.The polygamous males were wingless with extendible (solenogastrus) abdo men and mate inside the galls. These characters are also found in most Sycophaginae.The ancestor of Aganoidae was probably a primary sycophilous wasp, withdorsoventral depressed head, thorax and abdomen, that oviposit through thestylar channel as stiU Sycophaga sycomori does. Sycophaga wasps withits apterousand polyg amous males seem to be the sister group of Agaonidae. The Agaonidae females are characterized by their mandibular appendage and the antennalprocess. They have a prognathous head with gula. Themales are wingless polygamous andsolenogastrous. Key words: Agaonidae(Hymenoptera), mandibular appendage, evolution, phylogeny. Ficus is pollinated by small chalcidoid wasps and two or three antennal anelli. -

Pollinated by Pleistodontes Imperialis. (Ficus Carica); Most

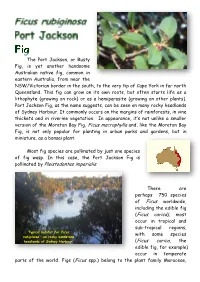

The Port Jackson, or Rusty Fig, is yet another handsome Australian native fig, common in eastern Australia, from near the NSW/Victorian border in the south, to the very tip of Cape York in far north Queensland. This fig can grow on its own roots, but often starts life as a lithophyte (growing on rock) or as a hemiparasite (growing on other plants). Port Jackson Fig, as the name suggests, can be seen on many rocky headlands of Sydney Harbour. It commonly occurs on the margins of rainforests, in vine thickets and in riverine vegetation. In appearance, it’s not unlike a smaller version of the Moreton Bay Fig, Ficus macrophylla and, like the Moreton Bay Fig, is not only popular for planting in urban parks and gardens, but in miniature, as a bonsai plant. Most fig species are pollinated by just one species of fig wasp. In this case, the Port Jackson Fig is pollinated by Pleistodontes imperialis. There are perhaps 750 species of Ficus worldwide, including the edible fig (Ficus carica); most occur in tropical and sub-tropical regions, Typical habitat for Ficus with some species rubiginosa – on rocky sandstone headlands of Sydney Harbour. (Ficus carica, the edible fig, for example) occur in temperate parts of the world. Figs (Ficus spp.) belong to the plant family Moraceae, which also includes Mulberries (Morus spp.), Breadfruit and Jackfruit (Artocarpus spp.). Think of a mulberry, and imagine it turned inside out. This might perhaps bear some resemblance to a fig. Ficus rubiginosa growing on a sandstone platform adjoining mangroves. Branches of one can be seen in the foreground, a larger one at the rear. -

The Dark Spreading Crowns of Moreton Bay Fig Trees Are a Glorious

The dark spreading crowns of Moreton Bay Fig Trees are a glorious feature of many Sydney parklands, for example Mrs Macquaries Chair, Hyde Park, the Domain and Moore Park. In their native habitat, these handsome trees can be found in eastern Australia, from south-eastern Queensland to Wollongong in southern NSW. Moreton Bay Figs, and many other fig species, can start life as seed that germinates in the branches of another tree, sending roots down to the ground. These roots and the trunk then thicken, enveloping the original host and eventually killing it. Figs with this growth habit are often referred to as banyans although in Australia we usually call them strangler figs. The fruit is edible, but not very palatable. However, they are particularly interesting and both structure and reproductive strategies are complex! Unlike most flowers with which we are familiar, fig flowers, both male and female, are extremely small and are produced on the INSIDE of the fruit which is technically referred to as a synconium. The flowers are pollinated by tiny fig wasps (Pleistodontes froggatti), with which the fig trees share an obligate mutual relationship. The figs depend on wasps for pollination, and the wasps can reproduce only in the female flowers. It had been thought that each fig species was pollinated by one specific wasp species but recent molecular studies have shown that some fig wasp species have been known to cheat, so the story isn’t quite as straight forward as originally envisaged. Pollination works like this: 1. Female wasps enter the fig and lay eggs in maturing female flowers. -

TAXON:Ficus Macrophylla Pers. SCORE:9.0 RATING:High Risk

TAXON: Ficus macrophylla Pers. SCORE: 9.0 RATING: High Risk Taxon: Ficus macrophylla Pers. Family: Moraceae Common Name(s): Australian banyan Synonym(s): Ficus magnolioides Borzì black fig Moreton Bay fig Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 15 Oct 2019 WRA Score: 9.0 Designation: H(Hawai'i) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Strangler Fig, Naturalized, Environmental Weed, Bird-Dispersed, Resprouts Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens y=1, n=0 y 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 n 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 15 Oct 2019 (Ficus macrophylla Pers.) Page 1 of 20 TAXON: Ficus macrophylla Pers. -

PROCEEDINGS of the HAWAIIAN SOCIETY for 1975

PROCEEDINGS of the HAWAIIAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY for 1975 VOL. XXII NO. 3 December 1977 Information for Contributors Manuscripts for publication, proof, and other editorial matters should be addressed to: Editor: Hawaiian Entomological Society c/o Department of Entomology University of Hawaii 3050 Maile Way. Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Manuscripts should not exceed 40 typewritten pages, including illustrations (approximately 20 printed pages). Longer manuscripts may be rejected on the basis of length, or be subject to additional page charges. Typing — Manuscripts must be typewritten on one side of white bond paper, 8-1/2 x II inches. Double space all text, including tables, footnotes, and reference lists. Margins should be a minimum of one inch. Underscore only where italics are intended in body of text, not in headings. Geographical names, authors names, and names of plants and animals should be spelled out in lull. Except for the first time they are used, scientific names of organisms may be abbreviated by using the first letter of the generic name plus the full specific name. Submit original typescript and one copy. Pages should be numbered consecutively. Place footnotes at the bottom of the manuscript page on which they appear, with a dividing line. Place tables separately, not more than one table per manuscript page, at end of manuscript. Make a circled notation in margin of manuscript at approximate location where placement of a table is desired. Use only horizontal lines in tables. Illustrations — Illustrations should be planned to fit the type page of 4-1/2x 7 inches, with appropriate space allowed for captions. -

Hawaiian Entomological Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE Hawaiian Entomological Society Editor Emeritus, O. H. Swezey Vol. XII, No. 1 For the Year 1943 August, 1944 This issue of the Proceedings is the first ever to appear without Mr. O. H. Swezey as its editor. After nearly forty years, at his own request, Mr. Swezey has relinquished the direction of this periodical in order to devote himself more fully to his studies of the native Hawaiian insect fauna. Under his editorship the Pro ceedings attained a position unique among journals of its kind, and constitutes an enduring monument to Mr. Swezey's long devotion to Hawaiian entomology. The amount of work he devoted to the production of the Proceedings cannot be fully appreciated by most of us. We know, however, that he has given to it the same fresh interest and zest which all phases of entomology claim from him. For the Society we wish to express our appreciation of his long and efficient service as editor, and the hope that as Editor Emeritus, he will continue for many years to counsel his successors on the editorial committee. JANUARY 11, 1943 The 445th meeting was held at the H.S.P.A. Experiment Sta tion on Monday, January 11, at 2:00 p.m., with President Hold- away in the chair. Members present: Messrs. Faxon, Fullaway, Holdaway, Krauss, Look, Marlowe, McBride, Nishida, Pemberton, Rosa, Sakimura, Stains, Swezey, Van Zwaluwenburg, Williams and Zimmerman. Visitor: Lt. R. L. Doutt, U.S.N. NOTES AND EXHIBITIONS Records from Kauai—Mr. Krauss presented the following data on material collected on Kauai: Stenotrupis marshalli Zimmerman; one specimen of this small weevil was taken at Lihue on October 18, 1942. -

Phylogenetic Relationships, Historical Biogeography and Character Evolution of G-Pollinating Wasps Carlos A

doi 10.1098/rspb.2000.1418 Phylogenetic relationships, historical biogeography and character evolution of g-pollinating wasps Carlos A. Machado1*, Emmanuelle Jousselin2, Finn Kjellberg2, Stephen G. Compton3 and Edward Allen Herre1 1SmithsonianTropical Research Institute, Apartado 2072, Balboa, Republic of Panama 2CNRS-CEFE, 1919 Route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier Ce¨ dex 5, France 3Centre for Ecology and Evolution, School of Biology, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Nucleotide sequences from the cytochrome oxidase I (COI) gene were used to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships among 15 genera of ¢g-pollinating wasps. We present evidence supporting broad-level co- cladogenesis with respect to most but not all of the corresponding groups of ¢gs. Using fossil evidence for calibrating a molecular clock for these data, we estimated the origin of the ¢g^wasp mutualism to have occurred ca. 90 million years ago. The estimated divergence times among the pollinator genera and their current geographical distributions corresponded well with several features of the break-up of the southern continents during the Late Cretaceous period. We then explored the evolutionary trajectories of two char- acteristics that hold profound consequences for both partners in the mutualism: the breeding system of the host (monoecious or dioecious) and pollination behaviour of the wasp (passive or active). The ¢g^ wasp mutualism exhibits extraordinarily long-term evolutionary stability despite clearly identi¢able con£icts of interest between the interactors, which are re£ected by the very distinct variations found on the basic mutualistic theme. Keywords: ¢g wasp ; pollination; biogeography; coevolution; Gondwana; mutualism species, some individuals produce only seed-bearing fruit 1. -

Evolution of the Mandibular Appendage in Fig Wasps (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae)

Rev. Biol. Trop., 39 (1): 87-95, 1991 Evolution of the mandibular appendage in fig wasps (Hymenoptera: Agaonidae) William Ramírez B. Escuela de Fitotecnia, Universidad de Costa Rica. (Rec. 20-IX-1990. Acep. 15-X-1990) Abstract: The phylogenetic value of the conformation of the mandibular appendages, the number of mandibular glands and other head characters in the Agaonidae are examined. The phylogenetic arrangement suggests that the pre agaonid had a normal bidentate mandible with two glands, and a undistinct facial groove as in sorne Diaziella (Sycoecinae), Sycophaga (Sycophaginae) and in related chalcidoid non-pollinating fig wasps. It also had thirteen-seg mented antennae; a long scape, severa! times longer than wide a long triangular pedicel, two or three anelli and eight flagellomeres with sensilla (as uniquely found in Tetrapus). The mandibular appendage apparently co-evolved with the development of the ostiolum of the syconium and the first mandibular appendage was fixed and had ridges or lamellae. A flexible hinge evolved later at its hase. The polygamous males were wingless with extendible (solenogastrus) abdo men and mate inside the galls. These characters are also found in most Sycophaginae. The ancestor of Aganoidae was probably a primary sycophilous wasp, with dorsoventral depressed head, thorax and abdomen, that oviposit through the stylar channel as still Sycophaga sycomori does. Sycophaga wasps with its apterous and polygamous males secm to be the sister group of Agaonidae. The Agaonidae females are characterized by their mandibular appendage and the antennal process. They have a prognathous head with gula. The males are wingless polygamous and solenogastrous. Key words: Agaonidae (Hymenoptera), mandibular appendage, evolution, phylogeny. -

Some Aspects of Pollination in Ficus Rubiginosa in Israel

Asian Journal of Life Sciences Fichman-Shuster V and Eisikowitch D. Asian J Life Sci 2: 107. Research Article DOI: 10.29011/2577-0241.1000107 Some Aspects of Pollination in Ficus Rubiginosa in Israel Fichman-Shuster V, Eisikowitch D* School of Plant Sciences and Food Security, The George. S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel- Aviv University, Ramat- Aviv, Israel *Corresponding author: Eisikowitch D, School of Plant Sciences and Food Security, The George. S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel- Aviv University, Ramat- Aviv 69978. Israel. E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Fichman-Shuster V and Eisikowitch D (2019) Some Aspects of Pollination in Ficus rubiginosa in Israel. Asian J Life Sci 2: 107. DOI: 10.29011/2577-0241.1000107 Received Date: 24 April, 2019; Accepted Date: 02 May, 2019; Published Date: 09 May, 2019 Abstract Ficus rubiginosa Desf. (Moraceae) is a west Australia tree naturally pollinated by aganoid wasp Pleistodontes imperialis. This tree was introduced into Israel and has since become a nuisance as a result of the ripe fig droppings. We reveal its original pollinator in Israel and describe its pollination behavior as a transition between topocentric and ethodynamic. The changes in fig style length and wasp ovipositor length and the tree’s ability for both selfing and cross-pollination indicate the possibility of this species’ high adaptation to various climate conditions, and its ability to establish easily in new niches and its consequent potential to become an invasive plant. Keywords: Ficus rubiginosa; Israel; Topocentric and ethody- Materials and Methods namic pollination; Invasive plants. Plant material Introduction The research took place on Tel-Aviv University campus, F.