Cytochrome P450 Oxidative Metabolism: Contributions to the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Efficacy of Xenobiotics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Histidine-Rich Proteins in the Biomineralization of Hemozoin Lisa Pasierb

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 2005 The Role of Histidine-Rich Proteins in the Biomineralization of Hemozoin Lisa Pasierb Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Pasierb, L. (2005). The Role of Histidine-Rich Proteins in the Biomineralization of Hemozoin (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1021 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Histidine-Rich Proteins in the Biomineralization of Hemozoin A Dissertation presented to the Bayer School of Natural and Environmental Sciences of Duquesne University As partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Lisa Pasierb August 26, 2005 Dr. David Seybert, thesis director Dr. David W. Wright, advisor In memory of Anna Pasierb April 24, 1924 – May 31, 2005 ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. David W. Wright. His exuberating energy and conviction attracted me to his research group, while his unwavering faith in me taught me more than he could ever know. Secondly, of course, I would like to extend my appreciation to Glenn Spreitzer and James Ziegler, the other two original members of the Wright group, whom initially tried to exert male dominance, but eventually became very faithful friends and colleagues. Finally, to all the other members of the Wright group over the years, thanks for all of your help, suggestions, and camaraderie. -

WO 2017/145013 Al 31 August 2017 (31.08.2017) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2017/145013 Al 31 August 2017 (31.08.2017) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C07D 498/04 (2006.01) A61K 31/5365 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, C07D 519/00 (2006.01) A61P 25/00 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, (21) Number: International Application DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/IB20 17/050844 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, (22) International Filing Date: KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, 15 February 2017 (15.02.2017) MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, (25) Filing Language: English RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, (26) Publication Language: English TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 62/298,657 23 February 2016 (23.02.2016) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (71) Applicant: PFIZER INC. [US/US]; 235 East 42nd Street, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, New York, New York 10017 (US). -

Dalbavancin • Oritavancin • Tedizolid • Ceftolozane/Tazobactam • Ceftazidime/Avibactam • Fecal Transplant

What’s New in Infectious Diseases? Bruce L. Gilliam, M.D. Institute of Human Virology University of Maryland School of Medicine Baltimore, MD Topics New Antibacterial Therapeutics Emerging Pathogens HIV Hepatitis C Disclosures Research Studies Pfizer – Staph aureus Vaccine Trial TaiMed Biologics - Ibaluzimab Advisory Board Viiv Healthcare New Antibacterial Therapeutics • Dalbavancin • Oritavancin • Tedizolid • Ceftolozane/tazobactam • Ceftazidime/avibactam • Fecal Transplant Incidence of Staph aureus hospitalizations in U.S.A., 2001–2009 BMC Infect Dis 2014, 14:296 Dalbavancin (Dalvance) • Derived from Teicoplanin • ½ life – Effective: 8.5 days – Terminal: 346 hrs (14 days) • Bactericidal • Similar spectrum to Vancomycin, active against: – Staphylococci • MSSA, MRSA, CoNS – Streptococci • resistant pneumococci • anaerobic strep – Enterococci • VRE with van B, C but not A – Corynebacterium Dalbavancin Once Weekly Non- Inferior to Vanco/Linezolid N Engl J Med 2014;370:2169-79. Single-Dose (1.5 g) Non-Inferior to Weekly Dalbavancin for Treatment of Acute Bacterial Skin and Skin Structure Infection 100 90 80 70 60 50 Single Dose 40 Once Weekly 30 20 10 0 Overall Clinical Success Rate Success Rate Success Rate Response Day 14 Day 28 Day 14 MRSA Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Nov 26. pii: civ982. [Epub ahead of print] VA Experience with Dalbavancin • Background – Levels in bone > MIC for 14 days • 8 patients treated for osteomyelitis with IV Dalbavancin – Former IV drug users not eligible for home IV or unwilling to do home IV • Treated for up to 8 weeks • No adverse events • All with resolution of osteomyelitis • Cost savings vs. placement in facility Oritavancin (Orbactiv) • Derived from Vancomycin • ½ life – Terminal 245-393 hrs (10-16 days) • Bactericidal • Similar spectrum to Vancomycin, active against: – Staphylococci • MSSA, MRSA, CoNS – Streptococci • resistant pneumococci • anaerobic strep – Enterococci • VRE with van A, B, C – Corynebacterium Single Dose Oritavancin vs. -

Corning® Supersomes™ Ultra Human Aldehyde Oxidase

Corning® Supersomes™ Ultra Human Aldehyde Oxidase Aldehyde Oxidase (AO) is a cytosolic enzyme that plays an important role in non-CYP mediated drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. AO has garnered significant attention in the pharmaceutical industry due to multiple drug failures during clinical trials that were associated with the AO pathway and an increase in the number of aromatic aza-heterocycle moieties found in drug leads that have been identified as substrates for AO. Traditionally, recombinant AO (rAO) is expressed in bacteria. However, this approach has disadvantages such as different protein post-translation modifications that lead to different function as compared to mammalian cells. Corning has developed Corning Supersomes Ultra Aldehyde Oxidase, a recombinant human AO enzyme utilizing a mammalian cell-based expression system to address these issues. This product will enable early assessment of the liability of AO for drug metabolism and clearance. Corning Supersomes Ultra Human Aldehyde Oxidase has been over-expressed in HEK-293 cells and exhibited a significantly higher activity as compared to AO expressed in E. coli. Time- dependent enzyme kinetics, using known substrates and inhibitors, between the rAO and the native form found in human liver cytosol produced a good correlation. Features and Benefits of Corning Supersomes Ultra Aldehyde Oxidase Mammalian cell expression system Corning Supersomes Ultra Human Aldehyde Oxidase Performance Corning Supersomes Ultra AO have been engineered in HEK-293 mammalian cells, thereby eliminating the biosafety concerns Activity Comparison Utilizing Probe Substrate (Zaleplon, 250 µM) associated with baculovirus. Stable and reliable in vitro tool 25 Corning Supersomes Ultra AO are a stable and reliable in vitro tool for the study of AO-mediated metabolism, which provides a 20 quantitative contribution of drug clearance. -

Jos Journal 2

POST-OPERATIVE AUDIT OF G6PD-DEFICIENT MALE CHILDREN WITH OBSTRUCTIVE ADENOTONSILLAR ENLARGEMENT AT UNIVERSITY COLLEGE HOSPITAL, IBADAN, NIGERIA. John EN1, Totyen EL1, Jacob N2, Nwaorgu OGB1 1 .Department of ENT/Head and Neck Surgery, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria 2. Department of paediatrics, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria All correspondences and request for reprint to Dr John EN, Department of ENT/Head and Neck Surgery, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Telephone: +2348036240109 Abstract Background: G6PD deficiency ranks among the commonest hereditary enzyme deficiency worldwide and notable as a predisposing condition to haemolyticcrises. The fear of possible untoward effects is often expressed by parents of G6PD deficient male children scheduled for surgery after obtaining an informed and understood consent. The parental perception of obstructive adenotonsillar enlargement in this condition was also appraised. Methods: A retrospective chart review of all G6PD deficient male children between ages 1 to 7years who had adenotonsillectomy over a 3year period at University college Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Results: The patients comprised of 22 G6PD deficient male children diagnosed shortly after birth upon development of neonatal jaundice. Fifteen(68.2%) and 6(27.3%) of the patients subsequently developed episodes of drug- induced haemolysis and non-haemolytic drug reactions prior to undergoing adenotonsillectomy by the otolaryngologists. None of the patients was observed to develop haemolytic crises up to 2weeks post-adenotonsillectomy. From the parental perception and responses in the follow-up period,all 22(100%) patient had resolution of noisy breathing, 20(91%) had improvement of snoring and apnoeic spells. Only 15 (68%) were reported to stop mouth-breathing. -

Annex 4: Drug Dosages for Children (Formulary)

Medicines Dosage Form Dose according to body weight (calculate if weight is below or over) 3-6 kg 6-10 kg 10-15 kg 15-20 kg 20-29 kg albendazole 200 mg (half tablet) 12-24 months chewable tablet, 400mg 400 mg (one tablet) over 24 months amodiaquine 10 mg base/kg/3 days (total dose 30 mg base/kg) tablet, 200mg - - 1 1 1 amoxicillin 15 mg/kg/dose for 7 days tablet/capsule 250 mg ¼ ½ ¾ 1 1½ oral suspension, 125mg/5ml 2.5 ml 5 ml 7.5 ml 10 ml - non-severe pneumonia: 25 mg/kg 2 times per day for 3 days tablet/capsule 250 mg ½ 1 1½ 2 2½ oral suspension, 125mg/5ml 5 ml 10 ml 15 ml - - ampicillin IM 50 mg/kg/6 hours Vial of 500 mg mixed with 2.1 ml 1 ml 2 ml 3 ml 5 ml 6 ml sterile water to give 500 mg/2.5 ml artemether IM 3.2 mg/kg once on day 1 injection, 40mg/ml in 1ml ampoule then injection, 80mg/ml in 1ml ampoule see Chapter 5, management of the child with malaria IM 1.6 mg/kg daily until oral therapy is possible, total therapy one week artemether + fixed dose treatment (20+120 mg) twice daily for 3 days tablet 10+120 mg see Chapter 5, management of the child with malaria lumefantrine artesunate severe malaria: IV or IM 2.4 mg/kg over 3 minutes at 0, 12 and 24 vial of 60 mg in 0.6 ml with 3.4 ml hours on day 1. -

Amino Acid Disorders

471 Review Article on Inborn Errors of Metabolism Page 1 of 10 Amino acid disorders Ermal Aliu1, Shibani Kanungo2, Georgianne L. Arnold1 1Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; 2Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo, MI, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: S Kanungo, GL Arnold; (II) Administrative support: S Kanungo; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: E Aliu, GL Arnold; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: None; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Georgianne L. Arnold, MD. UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, 4401 Penn Avenue, Suite 1200, Pittsburgh, PA 15224, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Amino acids serve as key building blocks and as an energy source for cell repair, survival, regeneration and growth. Each amino acid has an amino group, a carboxylic acid, and a unique carbon structure. Human utilize 21 different amino acids; most of these can be synthesized endogenously, but 9 are “essential” in that they must be ingested in the diet. In addition to their role as building blocks of protein, amino acids are key energy source (ketogenic, glucogenic or both), are building blocks of Kreb’s (aka TCA) cycle intermediates and other metabolites, and recycled as needed. A metabolic defect in the metabolism of tyrosine (homogentisic acid oxidase deficiency) historically defined Archibald Garrod as key architect in linking biochemistry, genetics and medicine and creation of the term ‘Inborn Error of Metabolism’ (IEM). The key concept of a single gene defect leading to a single enzyme dysfunction, leading to “intoxication” with a precursor in the metabolic pathway was vital to linking genetics and metabolic disorders and developing screening and treatment approaches as described in other chapters in this issue. -

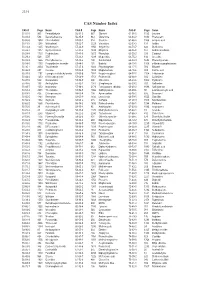

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSCRIPTOME, PROTEOME AND miRNA PROFILE OF KUPFFER CELLS AND MONOCYTES Andrey Elchaninov1,3*, Anastasiya Lokhonina1,3, Maria Nikitina2, Polina Vishnyakova1,3, Andrey Makarov1, Irina Arutyunyan1, Anastasiya Poltavets1, Evgeniya Kananykhina2, Sergey Kovalchuk4, Evgeny Karpulevich5,6, Galina Bolshakova2, Gennady Sukhikh1, Timur Fatkhudinov2,3 1 Laboratory of Regenerative Medicine, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology Named after Academician V.I. Kulakov of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia 2 Laboratory of Growth and Development, Scientific Research Institute of Human Morphology, Moscow, Russia 3 Histology Department, Medical Institute, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow, Russia 4 Laboratory of Bioinformatic methods for Combinatorial Chemistry and Biology, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 5 Information Systems Department, Ivannikov Institute for System Programming of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia 6 Genome Engineering Laboratory, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Moscow Region, Russia Figure S1. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted blood sample. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S2. Flow cytometry analysis of unsorted liver stromal cells. Representative forward, side scattering and histogram are shown. The proportions of negative cells were determined in relation to the isotype controls. The percentages of positive cells are indicated. The blue curve corresponds to the isotype control. Figure S3. MiRNAs expression analysis in monocytes and Kupffer cells. Full-length of heatmaps are presented. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Efficacy and Safety of Methylene Blue in the Treatment of Malaria: a Systematic Review G

Lu et al. BMC Medicine (2018) 16:59 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1045-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Efficacy and safety of methylene blue in the treatment of malaria: a systematic review G. Lu1,2, M. Nagbanshi2, N. Goldau2, M. Mendes Jorge2, P. Meissner3, A. Jahn2, F. P. Mockenhaupt4 and O. Müller2* Abstract Background: Methylene blue (MB) was the first synthetic antimalarial to be discovered and was used during the late 19th and early 20th centuries against all types of malaria. MB has been shown to be effective in inhibiting Plasmodium falciparum in culture, in the mouse model and in rhesus monkeys. MB was also shown to have a potent ex vivo activity against drug-resistant isolates of P. falciparum and P. vivax. In preclinical studies, MB acted synergistically with artemisinin derivates and demonstrated a strong effect on gametocyte reduction in P. falciparum. MB has, thus, been considered a potentially useful partner drug for artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT), particularly when elimination is the final goal. The aim of this study was to review the scientific literature published until early 2017 to summarise existing knowledge on the efficacy and safety of MB in the treatment of malaria. Methods: This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines. Studies reporting on the efficacy and safety of MB were systematically searched for in relevant electronic databases according to a pre-designed search strategy. The search (without language restrictions) was limited to studies of humans published until February 2017. Results: Out of 474 studies retrieved, a total of 22 articles reporting on 21 studies were eligible for analysis. -

Application for Inclusion of Artesunate/Amodiaquine Fixed Dose Combination Tablets in the Who Model Lists of Essential Medicines

SANOFI-AVENTIS artesunate/amodiaquine Application for inclusion in the WHO Model Lists of essential medicines June 2009- updated Sept. 2010 APPLICATION FOR INCLUSION OF ARTESUNATE/AMODIAQUINE FIXED DOSE COMBINATION TABLETS IN THE WHO MODEL LISTS OF ESSENTIAL MEDICINES Artesunate / Amodiaquine, Fixed dose combination 1/57 25 mg/ 67.5 mg, 50 mg/ 135 mg and 100 mg/270 mg SANOFI-AVENTIS artesunate/amodiaquine Application for inclusion in the WHO Model Lists of essential medicines June 2009- updated Sept. 2010 TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Summary statement of the proposal for inclusion p.4 2. Name of the focal point in WHO submitting or supporting the p.9 Application 3. Name of the organisation(s) consulted and/or supporting the p.10 Application 4. International Non-proprietary Name (INN, generic name) of p.10 the medicine 5. Dosage form or strength proposed for inclusion p.10 5.1. Chemical characteristics p.10 5.2. The formulation proposed for inclusion p.11 5.3. Stability of the formulation p.14 6. International availability – sources, if possible manufacturers p.14 6.1. Sources and manufacturers p.14 6.2. History of the product p.15 6.3. International availability and production capacity p.16 7. Whether listing is requested as an individual medicine or as an p.17 example of a group 8. Information supporting the public health relevance p.18 (epidemiological information on disease burden, assessment of current use, target population) 9. Treatment details p.22 9.1. Method of administration p.22 9.2. Dosage p.22 9.3. Duration p.22 9.4.