IDM Botswana SDM No 4.Pdf (596.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

356 Partners Found. Check If Available in Your Market

367 partners found. Check if available in your market. Please always use Quick Check on www.hahnair.com/quickcheck prior to ticketing P4 Air Peace BG Biman Bangladesh Airl… T3 Eastern Airways 7C Jeju Air HR-169 HC Air Senegal NT Binter Canarias MS Egypt Air JQ Jetstar Airways A3 Aegean Airlines JU Air Serbia 0B Blue Air LY EL AL Israel Airlines 3K Jetstar Asia EI Aer Lingus HM Air Seychelles BV Blue Panorama Airlines EK Emirates GK Jetstar Japan AR Aerolineas Argentinas VT Air Tahiti OB Boliviana de Aviación E7 Equaflight BL Jetstar Pacific Airlines VW Aeromar TN Air Tahiti Nui TF Braathens Regional Av… ET Ethiopian Airlines 3J Jubba Airways AM Aeromexico NF Air Vanuatu 1X Branson AirExpress EY Etihad Airways HO Juneyao Airlines AW Africa World Airlines UM Air Zimbabwe SN Brussels Airlines 9F Eurostar RQ Kam Air 8U Afriqiyah Airways SB Aircalin FB Bulgaria Air BR EVA Air KQ Kenya Airways AH Air Algerie TL Airnorth VR Cabo Verde Airlines FN fastjet KE Korean Air 3S Air Antilles AS Alaska Airlines MO Calm Air FJ Fiji Airways KU Kuwait Airways KC Air Astana AZ Alitalia QC Camair-Co AY Finnair B0 La Compagnie UU Air Austral NH All Nippon Airways KR Cambodia Airways FZ flydubai LQ Lanmei Airlines BT Air Baltic Corporation Z8 Amaszonas K6 Cambodia Angkor Air XY flynas QV Lao Airlines KF Air Belgium Z7 Amaszonas Uruguay 9K Cape Air 5F FlyOne LA LATAM Airlines BP Air Botswana IZ Arkia Israel Airlines BW Caribbean Airlines FA FlySafair JJ LATAM Airlines Brasil 2J Air Burkina OZ Asiana Airlines KA Cathay Dragon GA Garuda Indonesia XL LATAM Airlines -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

Fact Finding Airports Southern Africa

2015 FACT FINDING SOUTHERN AFRICA Advancing your Aerospace and Airport Business FACT FINDING SOUTHERN AFRICA SUMMARY GENERAL Africa is home to seven of the world’s top 10 growing economies in 2015. According to UN estimates, the region’s GDP is expected to grow 30 percent in the next five years. And in the next 35 years, the continent will account for more than half of the world’s population growth. It is obvious that the potential in Africa is substantial. However, African economies are still to unlock their potential. The aviation sector in Africa faces restrictive air traffic regimes preventing the continent from using major economic benefits. Aviation is vital for the progress in Africa. It provides 6,9 million jobs and US$ 80 million in GDP with huge potential to increase. Many African governments have therefore, made infrastructure developments in general and airport related investments in particular as one of their priorities to facilitate future growth for their respective country and continent as a whole. Investment is underway across a number of African airports, as the region works to provide the necessary infrastructure to support the continent’s growth ambitions. South Africa is home to most of the airports handling 1+ million passengers in Southern Africa. According to international data 4 out of 8 of those airports are within South African Territory. TOP 10 AIRPORTS [2014] - AFRICA CITY JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA 19 CAIRO, EGYPT 15 CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA 9 CASABLANCA, MOROCCO 8 LAGOS, NIGERIA 7,5 HURGHADA, EGYPT 7,2 ADDIS -

World Bank Document

ReportNo. 10667-ZA Zambia FinancialPerformance Public Disclosure Authorized of the Government-OwnedTransport Sector November1992 InfrastructureDivision MIC PCFICHE COPY SouthernAfrica Department F N. Type: (f Africa Region r i ti e: F INANCIAL FPF'RFOPMANCTE(F' THF CT FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Axt.': 3 B(: or2IJ11125 Dept.t :AFtN Ext. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Docunentof the World Bank Thisdocument has a restricteddistribution and may be used by recipients -onilyin theperformance of theirofficial duties. Its contents mnay not otherwise b!etisclosedwithout World Bank authorization. ZAMBIA CU ECEYOIVALENTS CurrencyUnit - ZambianKwacha ExchangeRates YM ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Kper US Do:lar 1987 8.9 1988 8.2 1989 12.9 1990 29.0 1991 50.0 1992(assumed average) 120.0 FISCAJ.YEARS Government:January 1 - December31 TransportEnterprises: April 1 - March31 ABBREVIATIONS AJAS - AfricanJoint Air Services BAU - Business-As-Usual BP - BritishPetroleum Ltd. CHL - ContractH-aulage Ltd CSO - CentralStatistical Office DC - DistrictCouncils DCA - Departmentof CivilAviation EEC - EuropeanEconomic Community ESCO - EngineeringServices Corporation Ltd IATA - InternationalAir TransportAssociation km - Kilometer MC&T - Ministryof Communicationsand Transport MH - MpulunguHarbor Corporation Ltd M-Roads - MainRoads MSD - MechanicalServices Department MT - MulungushiTraveller Ltd NACL - NationalAirports Corporation Ltd PSO - PuDlicService Obligation PTA - PreferentialTrade Area RD - RoadsDepartment SADCC - SouthAfrican -

Apartheid by Air

Apartheid by air http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nizap1031 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Apartheid by air Author/Creator Ruyter, Theo Publisher Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika (KZA) Date 1990-00-00 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, Tanzania, United Republic of, Netherlands Coverage (temporal) 1985 - 1990 Source NIZA Description On air links with South Africa and the international campaign against them; special attention paid to KLM and action initiated in 1985 by Dutch SNV volunteers working at Mazimbu (ANC’s Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College) and other places in Tanzania. -

Zambia's Ambassador to Germany, H.E. Anthony Mukwita Meets

Zambia’s ambassador to Germany, H.E. Anthony Mukwita meets German Chancellor Angela Merkel PUBLISHER Embassy of Zambia - Berlin Ambassador / Botshafter Anthony Mukwita EDITOR Kellys Kaunda First Secretary Press [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Pictures of President obtained via State House Press Ofce headed by Special Assistant- Press and Public Relations taken by Eddie Mwanaleza, Salim Henry and Thomas Nsama. Extra write ups by Kellys Kaunda, Amos Chanda, Bernadette Deka, Chileshe Kandeta. MAKERTING/ADVERTISING Kellys Kaunda [email protected] The Diplomatic Dispatch is a quarterly magazine of the Embassy of Zambia in Berlin, Germany. The purpose of the publication is to promote the vast opportunities that exist in Zambia in various Zambia Berlin Embassy felds such as agriculture, mining and tourism to mention but a few. It is distributed to all govern- ment ministries in Zambia, all missions globally where Zambia is represented and all missions and Axel Springer Street sections of business associations and chambers of commerce in Germany. It is about the good 54a, Berlin, Germany story of Zambia known mostly for peace and stability as well as a tool for Economic Diplomacy. … the FOCAC Summit : What are the opportunities for Zambia? By Bernadette Deka - Executive director Policy Monitoring Research Center, PMRC he 3rd edition of the Forum for Africa – China Cooper- During the FOCAC summit, 8 new initiatives were an- ation (FOCAC) came to an end on 4th September nounced backed by a new US$60 billion support to Africa T 2018. We now refect on what has been deliberated for the next 3 years. These are: and more so, what Zambia has benefted. -

Refund Policy & Procedures

REFUND POLICY & PROCEDURES Page | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM INDEX PAGE 1. General Information 3 2. Types of Refunds 5 3. Refund Procedures 12 4. Turnaround Time of Refunds 14 Page | 2 AIR BOTSWANA REFUND POLICY 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 This revised policy replaces the October 2009 Air Botswana Refund Policy and shall effect on 1st October 2018. 1.2 A refund of an Air ticket is the cancellation of a business, either by a passenger being a no-show, a flight being cancelled or delayed or unforeseen circumstances preventing a passenger to travel and is only to be processed by the airline that issued the original document. Only the original issuing Airline should refund a ticket, as the value of a document is frequently unrecognizable or illegible due to coupon information that includes high provision payments. In most cases the issuing airline is the only one able to decide the actual value of these documents. 1.3 Any ticket or unused portion thereof will be refunded in accordance with the applicable fare rules or tariffs. 1.4 A Refund means the repayment to the purchaser of all or a portion of a fare, rate or charge for unused carriage of service and will only be paid back in the original form of payment as follows: 1.4.1 Cash/Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) - in this case a cheque/EFT will be issued to the sponsor. 1.4.2 Cheque - verify that the cheque has been cleared with the bank before a refund is processed. 1.4.3 Credit card- Payment shall be made only to the Credit Card Holder. -

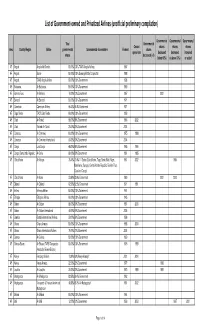

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aerom

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aeromas African Intl Air Afrique #1 Air Afrique #2 Air Algerie Air Atlas Air Austral Air Botswana Air Brousse Air Cameroon Air Cape Air Carriers Air Djibouti Air Centrafique Air Comores Air Congo Air Gabon Air Gambia Air Ivoire Air Kenya Aviation Airlink Air Lowveld Air Madagascar Air Mahe Air Malawi Air Mali Air Mauritanie Air Mauritius Air Namibia Box 2 Air Rhodesia Air Senegal Air Seychelles Air Tanzania Air Zaire Air Zimbabwe Aircraft Operating Co. Alliances Avex Avia Bechuanaland Natl. Bellview Bop Air Cameroon Airlines Campling Bros. Capital Air Caspair / Caspar Cata Catalina Safari Central African Airways Christowitz Clairways Command Airways Commercial Air Service Copperbelt Court Heli DAS – Dairo Desert Airways Deta DTA Angola East African Airways Corp Eastern Air Zambia Egypt Air Elders Colonial Box 3 Ethiopian Federal Airlines Sudan Flite Star Gambia Airways German Ghana Airways Guinea Hold – Trade Hunting Clan Imperial Inter Air International Air Kitale Zaire Katanga Kenya Airways Lam Lara Leopard Air Lana Lesotho Airways Liverian National Libyan Arab Magnum MISR Namib Air National Nigeria Airways North African Airlines (Tunisia) Phoenix Protea Pyramid RAC – Rhodesia Regie Malgache R.A.N.A Rhodesian Air Service Box 4 Rossair Royal Air Maroc Royal Swazi Ruac Sa Express Safair Safari Air Svcs Saide Sata Algeria SATT Scibe Shorouk Sierra Leone Airlines Skyways Sobelair South African Aerial Transport Somali Airlines