Temples, Sacred Objects, and Associated Rituals Figure 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple

DOI: 10.4467/25438700ŚM.17.058.7679 MYROSLAV YATSIV* Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple Abstract Main tendencies, appropriateness and features of the embodiment of the architectural and theological essence of the light are defined in architecturally spatial organization of the Orthodox Church; the value of the natural and artificial light is set in forming of symbolic structure of sacral space and architectonics of the church building. Keywords: the Orthodox Church, sacral space, the light, architectonics, functions of the light, a system of illumination, principles of illumination 1. Introduction. The problem raising in such aspect it’s necessary to examine es- As the experience of new-built churches testifies, a process sence and value of the light in space of the of re-conceiving of national traditions and searches of com- Orthodox Church. bination of modern constructions and building technologies In religion and spiritual life of believing peo- last with the traditional architectonic forms of the church bu- ple the light is an important and meaningful ilding in modern church architecture of Ukraine. Some archi- symbol of combination in their imagination tects go by borrowing forms of the Old Russian church archi- of the celestial and earthly worlds. Through tecture, other consider it’s better to inherit the best traditions this it occupies a central place among reli- of wooden and stone churches of the Ukrainian baroque or gious characters which are used in the Saint- realize the ideas of church architecture of the beginning of ed Letter. From the first book of Old Testa- XX. In the east areas the volume-spatial composition of the ment, where the fact of creation of the light Russian “synod-empire” of the church style is renovated as by God is specified: “And God said: “Let it be the “national sign of church architecture” and interpreted as light!”(Genesis 1.3-4), to the last New Testa- the new “Ukrainian Renaissance” [1]. -

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020

Religious Studies 300 Second Temple Judaism Fall Term 2020 (3 credits; MW 10:05-11:25; Oegema; Zoom & Recorded) Instructor: Prof. Dr. Gerbern S. Oegema Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University 3520 University Street Office hours: by appointment Tel. 398-4126 Fax 398-6665 Email: [email protected] Prerequisite: This course presupposes some basic knowledge typically but not exclusively acquired in any of the introductory courses in Hebrew Bible (The Religion of Ancient Israel; Literature of Ancient Israel 1 or 2; The Bible and Western Culture), New Testament (Jesus of Nazareth, New Testament Studies 1 or 2) or Rabbinic Judaism. Contents: The course is meant for undergraduates, who want to learn more about the history of Ancient Judaism, which roughly dates from 300 BCE to 200 CE. In this period, which is characterized by a growing Greek and Roman influence on the Jewish culture in Palestine and in the Diaspora, the canon of the Hebrew Bible came to a close, the Biblical books were translated into Greek, the Jewish people lost their national independence, and, most important, two new religions came into being: Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism. In the course, which is divided into three modules of each four weeks, we will learn more about the main historical events and the political parties (Hasmonaeans, Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, etc.), the religious and philosophical concepts of the period (Torah, Ethics, Freedom, Political Ideals, Messianic Kingdom, Afterlife, etc.), and the various Torah interpretations of the time. A basic knowledge of this period is therefore essential for a deeper understanding of the formation of the two new religions, Early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, and for a better understanding of the growing importance, history and Biblical interpretation have had for Ancient Judaism. -

Architecture for Worship: Re-‐Thinking Sacred Space in The

Architecture for Worship: Re-Thinking Sacred Space in the Contemporary United States of America RICHARD S. VOSKO The purpose of this paper is to examine the symbolic value of religious buildings in the United States. It will focus particularly on places of worship and the theologies conveyed by them in an ever-changing socio-religious landscape. First, I will cite some of the emerging challenges that surface when thinking about conventional religious buildings. I will then describe those architectural "common denominators" that are important when re-thinking sacred space in a contemporary age. Churches, synagogues, and mosques exist primarily because of the convictions of the membership that built them. The foundations for these spaces are rooted in proud traditions and, sometimes, the idealistic hopes of each congregation. In a world that is seemingly embarked on a never-ending journey of war, poverty, and oppression these structures can be oases of peace, prosperity, and justice. They are, in this sense, potentially sacred spaces. The Search for the Sacred The search for the sacred is fraught with incredible distractions and challenges. The earth itself is an endangered species. Pollution is taken for granted. Rain forests are being depleted. Incurable diseases kill thousands daily. Millions have no pure water to drink. Some people are malnourished while others throw food away. Poverty and wealth live side by side, often in the same neighborhoods. Domestic abuse traumatizes family life. Nations are held captive by imperialistic regimes. And terrorism lurks everywhere. What do religious buildings, particularly places of worship, have to say about all of this? Where do homeless, hungry, abused, and stressed-out people find a sense of the sacred in their lives? One might even ask, where is God during this time of turmoil and inequity? By some estimates nine billion dollars were spent on the construction of religious buildings in the year 2000. -

Redalyc.Visiting a Hindu Temple: a Description of a Subjective

Ciencia Ergo Sum ISSN: 1405-0269 [email protected] Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México México Gil-García, J. Ramón; Vasavada, Triparna S. Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations Ciencia Ergo Sum, vol. 13, núm. 1, marzo-junio, 2006, pp. 81-89 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Toluca, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10413110 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Visiting a Hindu Temple: A Description of a Subjective Experience and Some Preliminary Interpretations J. Ramón Gil-García* y Triparna S. Vasavada** Recepción: 14 de julio de 2005 Aceptación: 8 de septiembre de 2005 * Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, Visitando un Templo Hindú: una descripción de la experiencia subjetiva y algunas University at Albany, Universidad Estatal de interpretaciones preliminares Nueva York. Resumen. Académicos de diferentes disciplinas coinciden en que la cultura es un fenómeno Correo electrónico: [email protected] ** Estudiante del Doctorado en Administración complejo y su comprensión requiere de un análisis detallado. La complejidad inherente al y Políticas Públicas en el Rockefeller College of estudio de patrones culturales y otras estructuras sociales no se deriva de su rareza en la Public Affairs and Policy, University at Albany, sociedad. De hecho, están contenidas y representadas en eventos y artefactos de la vida cotidiana. -

The Psalms As Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A

4 The Psalms as Hymns in the Temple of Jerusalem Gary A. Rendsburg From as far back as our sources allow, hymns were part of Near Eastern temple ritual, with their performers an essential component of the temple functionaries. 1 These sources include Sumerian, Akkadian, and Egyptian texts 2 from as early as the third millennium BCE. From the second millennium BCE, we gain further examples of hymns from the Hittite realm, even if most (if not all) of the poems are based on Mesopotamian precursors.3 Ugarit, our main source of information on ancient Canaan, has not yielded songs of this sort in 1. For the performers, see Richard Henshaw, Female and Male: The Cu/tic Personnel: The Bible and Rest ~(the Ancient Near East (Allison Park, PA: Pickwick, 1994) esp. ch. 2, "Singers, Musicians, and Dancers," 84-134. Note, however, that this volume does not treat the Egyptian cultic personnel. 2. As the reader can imagine, the literature is ~xtensive, and hence I offer here but a sampling of bibliographic items. For Sumerian hymns, which include compositions directed both to specific deities and to the temples themselves, see Thorkild Jacobsen, The Harps that Once ... : Sumerian Poetry in Translation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), esp. 99-142, 375--444. Notwithstanding the much larger corpus of Akkadian literarure, hymn~ are less well represented; see the discussion in Alan Lenzi, ed., Reading Akkadian Prayers and Hymns: An Introduction, Ancient Near East Monographs (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 56-60, with the most important texts included in said volume. For Egyptian hymns, see Jan A%mann, Agyptische Hymnen und Gebete, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999); Andre Barucq and Frarn;:ois Daumas, Hymnes et prieres de /'Egypte ancienne, Litteratures anciennes du Proche-Orient (Paris: Cerf, 1980); and John L. -

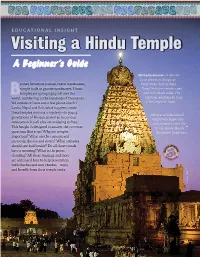

Visiting a Hindu Temple

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT Visiting a Hindu Temple A Beginner’s Guide Brihadeeswarar: A massive stone temple in Thanjavur, e they luxurious palaces, rustic warehouses, Tamil Nadu, built by Raja simple halls or granite sanctuaries, Hindu Raja Chola ten centuries ago B temples are springing up all over the and still vibrant today. The world, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. capstone, weighing 80 tons, Yet outside of India and a few places like Sri is the largest in India. Lanka, Nepal and Bali, what happens inside these temples remains a mystery—to young This special Educational generations of Hindus as well as to curious Insight was inspired by newcomers. It’s all a bit intimidating at first. and produced expressly This Insight is designed to answer the common for the Hindu Mandir questions that arise: Why are temples Executives’ Conference important? What are the customs and protocols, the dos and don’ts? What attitudes should one hold inside? Do all those rituals ATI O C N U A D have a meaning? What is the priest L E chanting? All these musings and more I N S S T are addressed here to help newcomers— I G H both Hindus and non-Hindus—enjoy and benefit from their temple visits. dinodia.com Quick Start… Dress modestly, no shorts or short skirts. Remove shoes before entering. Be respectful of God and the Gods. Bring your problems, prayers or sorrows but leave food and improper manners outside. Do not enter the shrines without invitation or sit with your feet pointing toward the Deities or another person. -

A Guide to Temple Safety and Security About HAF

A Guide to Temple Safety and Security About HAF The Hindu American Foundation (HAF) is a non-profit advocacy organization for the Hindu American community. Founded in 2003, HAF’s work impacts a range of issues—from the portrayal of Hinduism in K-12 textbooks to civil and human rights to addressing contemporary problems, such as environmental protection and inter-religious conflict, by applying Hindu philosophy. Why Do We Need This Guide At more than three million strong, the Hindu American community is one of the fastest growing American religious communities. While most Hindus are of South Asian origin, the Hindu American community includes individuals of Caribbean, African, South American, Southeast Asian, and Caucasian descent. To maintain a connection to their faith, the Hindu American community relies on a network of nearly 1000 temples spread out over 45 states. These temples, varied and diverse in their practices, serve as spiritual centers, community nexuses, and cultural hubs. The growth and resilience of Hindu temples mirrors that of the community itself. However, as they grow more visible, Hindu temples face unique challenges, ranging from hostility of surrounding communities and government bureaucracy to hate crimes and violence. This guide was created by the Hindu American Foundation to serve as a resource for temple leaders, enabling them to navigate these challenges, and maintain a vibrant, active, and secure temple community. Hindu American Foundation // A Guide to Temple Safety and Security // 1 Hate Crimes The Hindu American community has a long history of being targeted for hate crimes. From the “dotbuster gangs” that attacked Hindu men and women wearing tilak during the 1980s to the recent attack on a Kentucky Hindu temple, the community has sought to combat hate crimes effectively. -

The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism. Nancy Perkins East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2011 The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism. Nancy Perkins East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Perkins, Nancy, "The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1397. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1397 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History _____________________ by Nancy Perkins December 2011 _____________________ William D. Burgess Jr., PhD, Chair Keith Green, PhD Henry Antkiewicz, PhD Keywords: Book of Enoch, Judaism, Second Temple ABSTRACT The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism by Nancy Perkins This thesis examines the ancient Jewish text the Book of Enoch, the scholarly work done on the text since its discovery in 1773, and its seminal importance to the study of ancient Jewish history. Primary sources for the thesis project are limited to Flavius Josephus and the works of the Old Testament. Modern scholars provide an abundance of secondary information. -

The Role of Five Elements of Nature in Temple Architecture Ar

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 8, Issue 7, July-2017 1149 ISSN 2229-5518 The Role of Five Elements of Nature In Temple Architecture Ar. Snigdha Chaudhary Abstract— Examine the extensive influence of the selected theories of nature in Architecture namely element of nature effects the role of five ele- ments in Temple Architecture. “Theory of five elements of nature in context to the Temple Architectural Design ‘To make student understand the basic principles of five elements of nature so that it forms the basics for study of temple design through these topics.One should have a reasonable under- standing of its operational and economic implications, and lastly “To Evaluate the understanding of the relationship between space and design through five elements of nature’’ with the help of Hindu Temple Architecture. Index Terms— Temple architecture, five elements of nature, human perception of architectural expression, and temple concept through cosmology and philosophy —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION NDIA is well known for its rich heritage and variety of India, however while the basic elements of the temple are the I culture. Temples have always played an important role in same, the form and scale varied. For example as in the case of India's history and culture. There are more than 6 lakh the architectural elements like Sikhara (pyramidical roofs) and temples in India and about 1,80,000 temples in South India. Gopurams (the gateways). India is not only famous for various states but also for the cultures and such historic background that the past still has 2 ELEMENTS OF HINDU TEMPLE so much power on the present world. -

Should Israel Build the Third Temple?

Mon 15 July 2013 / 9 Av 5773 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Discussion for Tish’a b’Av eve Should Israel build the Third Temple? Background -Tish'a b'Av commemorates the destruction of the two Temples in Jerusalem -The First Temple, destroyed by the Babylonians in 587 BCE -The Second Temple, destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE Also, many other tragedies in Jewish history happened on that day, by accident or design. -For 2000 years Jews have prayed for the rebuilding of the Temple (Bet HaMikdash). -Rebuilding was not possible because the site was controlled by the Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Arabs, Seljuks, Crusaders, Mongols, Mamelukes, Turks, British, and Jordanians. -But Jews control the site today, since 7 June 1967, for the first time since biblical days. -Although most nations feel they have a say in what happens to Jerusalem. -A group called “The Temple Mount Faithful” routinely tries to set up a foundation stone for the Third Temple on Tisha b'Av, and the Israeli police routinely stop them. So, should we rebuild the Temple? Yes: -More and more Jews want it -We long for it daily in traditional Jewish prayers -It's our historical right -It would be a focal point, a rallying point for world Jewry No: -Don't want to go back to sacrificial worship. -Can only be on Temple Mount in Jerusalem (close to Western Wall). But that site is occupied by the Islamic Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque, third holiest site in Islam. Islamists would wage holy war. -

Temple College

Texas Pathways Institute #4 High School Pathway Connections Presenters Dr. Susan Guzmán-Treviño, Dr. Daniel Spencer Kristen Griffith Interim Vice President, Associate Vice President, Director, Dual Credit Educational Services Academic Outreach and Extended Programs Objectives • Temple College Background • ISD Partner Profiles • Top Transfer Colleges and Universities • Impetus for Mapping Work • 2-year to 4-year Transfer Model Pathways • High School Endorsement to 2-year Transfer Model Pathways Te m p l e C o l l e g e • Established in 1926 • Current Enrollment – 5,158 • Locations: • Main Campus-Temple, Texas • Texas Bioscience Institute-Baylor Scott & White Health West Campus • East Williamson County Higher Education Center – MITC • Hutto, Texas • Taylor, Texas Te m p l e C o l l e g e • Taxing District • Temple ISD • City of Temple • Service Area – 17 ISDs • Open Door Institution • AA, AS,AAS, Certificates, ABE, Workforce, Community Education, Marketable Skill Awards Te m p l e C o l l e g e • Service Area (In addition to TISD and the Municipality of Temple) • Bell County - Academy, Bartlett, Belton, Holland, Rogers, Troy, and Salado ISDs • Williamson County - Granger, Hutto, Taylor, and Thrall ISDs • Milam County - Buckholts, Cameron, Rockdale, and Thorndale ISDs • The part of Rosebud-Lott ISD & Bartlett ISD located in Milam County Temple College Service Area ISD Partner Profiles • Three largest ISDs: Temple, Belton*, Hutto* • Other ISDs served-mostly small rural • Most ISDs economically disadvantaged (free and reduced lunch) • ISDs