For Both Jews and Muslims the Temple Mount

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

Faith and Conflict in the Holy Land: Peacemaking Among Jews, Christians, and Muslims

ANNUAL FALL McGINLEY LECTURE Faith and Conflict in the Holy Land: Peacemaking Among Jews, Christians, and Muslims The Reverend Patrick J. Ryan, S.J. Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society RESPONDENTS Abraham Unger, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Government and Politics Wagner College Ebru Turan, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of History Fordham University Tuesday, November 12, 2019 | Lincoln Center Campus Wednesday, November 13, 2019 | Rose Hill Campus 3 Faith and Conflict in the Holy Land: Peacemaking Among Jews, Christians, and Muslims The Reverend Patrick J. Ryan, S.J. Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society Let me begin on holy ground, Ireland. In 1931 William Butler Yeats concluded his short poem, “Remorse for Intemperate Speech,” with a stanza that speaks to me as the person I am, for better or for worse: Out of Ireland have we come. Great hatred, little room, Maimed us at the start. I carry from my mother’s womb A fanatic heart. Ireland is, indeed, a small place, and it has seen great fanaticism and hatred, although the temperature of Ireland as a whole has subsided dramatically since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, despite Boris Johnson. The whole island of Ireland today occupies 32,599 square miles. British-administered Northern Ireland includes 5,340 of those square miles. Combined Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland approximate the size of Indiana. The total population of the island of Ireland is 6.7 million people, about a half a million more than the population of Indiana. There is another place of “great hatred, little room” that I wish to discuss this evening: the Holy Land, made up today of the State of Israel and the Palestinian autonomous regions of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. -

The Concepts of Al-Halal and Al-Haram in the Arab-Muslim Culture: a Translational and Lexicographical Study

The concepts of al-halal and al-haram in the Arab-Muslim culture: a translational and lexicographical study NADER AL JALLAD University of Jordan 1. Introduction This paper1 aims at providing sufficient definitions of the concepts of al-Halal and al-Haram in the Arab-Muslim culture, illustrating how they are treated in some bilingual Arabic-English dictionaries since they often tend to be provided with inaccurate, lacking and sometimes simply incorrect definitions. Moreover, the paper investigates how these concepts are linguistically reflected through proverbs, collocations, frequent expressions, and connota- tions. These concepts are deeply rooted in the Arab-Muslim tradition and history, affecting the Arabs’ way of thinking and acting. Therefore, accurate definitions of these concepts may help understand the Arab-Muslim identity that is vaguely or poorly understood by non-speakers of Arabic. Furthermore, to non-speakers of Arabic, these notions are often misunderstood, inade- quately explained, and inaccurately translated into other languages. 2. Background and Methodology The present paper is in line with the theoretical framework, emphasizing the complex relationship between language and culture, illustrating the importance of investigating linguistic data to understand the Arab-Muslim vision of the world. Linguists like Boas, Sapir and Whorf have extensively studied the multifaceted relationship between language and culture. Other examples are Hoosain (1991), Lucy (1992), Gumperz y Levinson (1996), 1 This article is part of the linguistic-cultural research done by the research group HUM-422 of the Junta de Andalucía and the Research Group of Experimental and Typological Linguistics (HUM0422) of the Junta de Andalucía and the Project of Quality Research of the Junta de Andalucia P06-HUM-02199 Language Design 10 (2008: 77-86) 78 Nader al Jallad Luque Durán (2007, 2006a, 2006b), Pamies (2007, 2008) and Luque Nadal (2007, 2008). -

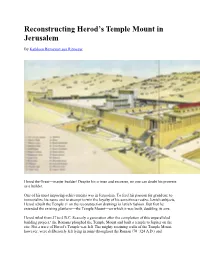

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

1 the Role of the Women in Fighting the Enemies [Please Note: Images

The Role Of The Women In Fighting The Enemies [Please note: Images may have been removed from this document. Page numbers have been added.] By the martyred Shaykh, Al-Hafith Yusuf Bin Salih Al-‘Uyayri (May Allah have Mercy upon him) Introduction In the Name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Most Merciful Verily all praise is due to Allah, and may the Peace and Blessings of Allah be upon the Messenger of Allah, his family and all of his companions. To proceed: My honoured sister, Indeed for you is an important and great role; and you must rise and fulfill your obligatory role in Islam 's confrontation of the new Crusade being waged by all the countries of the world against Islam and the Muslims. I will address you in these papers, and I will prolong this address due only to the importance of the topic; [a topic] that is in need of double these papers. So listen, may Allah protect and preserve you. The Muslim Ummah today is suffering from types of disgrace and humiliation that cannot be enumerated; [disgrace and humiliation] that it was not familiar with in its previous eras, and were never as widespread as they are today. And this disgrace and humiliation is not a result of the smallness of the Islamic Ummah or its poverty - it is counted as the largest Ummah today, just as it is the only Ummah that possesses the riches and elements that its enemies do not possess. And the question that presents itself is: what is the reason for this disgrace and humiliation that the Ummah suffers from today, when it is not in need of money or men? We say that -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 2 2000 Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Imseis, Ardi. "Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1039-1069. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTS ON THE GROUND: AN EXAMINATION OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ARDI IMSEIS* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1040 I. BACKGROUND ........................................... 1043 A. ISRAELI LAW, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND EAST JERUSALEM SINCE 1967 ................................. 1043 B. ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ......... 1047 II. FACTS ON THE GROUND: ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ACTIVITY IN EAST JERUSALEM ........................ 1049 A. EXPROPRIATION OF PALESTINIAN LAND .................. 1050 B. THE IMPOSITION OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ............... 1052 C. ZONING PALESTINIAN LANDS AS "GREEN AREAS"..... -

Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple

DOI: 10.4467/25438700ŚM.17.058.7679 MYROSLAV YATSIV* Architecture of Light of the Orthodox Temple Abstract Main tendencies, appropriateness and features of the embodiment of the architectural and theological essence of the light are defined in architecturally spatial organization of the Orthodox Church; the value of the natural and artificial light is set in forming of symbolic structure of sacral space and architectonics of the church building. Keywords: the Orthodox Church, sacral space, the light, architectonics, functions of the light, a system of illumination, principles of illumination 1. Introduction. The problem raising in such aspect it’s necessary to examine es- As the experience of new-built churches testifies, a process sence and value of the light in space of the of re-conceiving of national traditions and searches of com- Orthodox Church. bination of modern constructions and building technologies In religion and spiritual life of believing peo- last with the traditional architectonic forms of the church bu- ple the light is an important and meaningful ilding in modern church architecture of Ukraine. Some archi- symbol of combination in their imagination tects go by borrowing forms of the Old Russian church archi- of the celestial and earthly worlds. Through tecture, other consider it’s better to inherit the best traditions this it occupies a central place among reli- of wooden and stone churches of the Ukrainian baroque or gious characters which are used in the Saint- realize the ideas of church architecture of the beginning of ed Letter. From the first book of Old Testa- XX. In the east areas the volume-spatial composition of the ment, where the fact of creation of the light Russian “synod-empire” of the church style is renovated as by God is specified: “And God said: “Let it be the “national sign of church architecture” and interpreted as light!”(Genesis 1.3-4), to the last New Testa- the new “Ukrainian Renaissance” [1].