Mitogenomes Illuminate the Origin and Migration Patterns of the Indigenous People of the Canary Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoria Anual 2017

MemoriaMemoria 20172017 GrupoFundación DISA DISA Dirección: Fundación DISA Redacción: DISA, Departamento de Comunicación Metrópolis Comunicación Diseño y maquetación: AS Publicidad Impresión: Gráficas Sabater Fotografías: Archivo Fundación DISA y entidades colaboradoras Depósito legal: TF558-2018 www.fundaciondisa.org memoria 2 17 Sumario 6 La Fundación Carta del presidente 8 Nuestro compromiso 10 La Fundación en cifras 12 Acciones destacadas 16 Escuela de Familias 18 Desafi - Arte 22 DisaLab: Laboratorio Marino 26 Áreas de actuación 32 Deportiva 34 Cultural 50 Social 66 Medioambiental 84 Científica-Educativa y de Investigación 96 Comunicación 120 Premios y reconocimientos 122 Información económica 124 Órganos de gobierno y equipo 126 Entidades colaboradoras 128 Agradecimientos 130 Carta del Presidente Raimundo Baroja Rieu Presidente Es un placer poder presentar en esta Memoria y consejos de reconocidos expertos sobre nuevos las actividades que nuestra Fundación ha realiza- métodos en la educación en valores de los niños. do durante el año 2017. Ha sido un año lleno de Desafi-Arte, un proyecto que ha supuesto una opor- acciones que nos ha permitido reforzar nuestro tunidad para personas con capacidades diferentes, compromiso con la sociedad, potenciando el de- convirtiéndolas en creadoras de arte, y dándoles porte, la cultura, la protección del medio ambien- la oportunidad de demostrar hasta dónde son ca- te, la ciencia o la investigación. paces de llegar. Y DISALab, que con su cambio de contenido, y adentrándose en el mar, supone un La educación sigue siendo el eje central de nues- refuerzo académico para profesores y alumnos de tras actuaciones, concentrándonos en los más toda Canarias, ampliando los conocimientos sobre pequeños, independientemente de cuales sean del mundo marino en nuestras islas. -

Iii Jornadas De Historia Del Sur De Tenerife

III JORNADAS DE HISTORIA DEL ENERIFE T SUR DE TENERIFE DE UR S DEL ISTORIA H DE ORNADAS III J III CONCEJALÍA DE PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO III Jornadas de Historia del Sur de Tenerife Candelaria · Arafo · Güímar · Fasnia · Arico Granadilla de Abona · San Miguel de Abona Vilaflor · Arona · Adeje · Guía de Isora · Santiago del Teide III Jornadas de Historia del Sur de Tenerife Candelaria · Arafo · Güímar · Fasnia · Arico Granadilla de Abona · San Miguel de Abona Vilaflor · Arona · Adeje · Guía de Isora · Santiago del Teide Las III Jornadas de Historia del Sur de Tenerife tuvieron lugar en Arona durante el mes de noviembre de 2013 D. Francisco José Niño Rodríguez Alcalde-Presidente Del Ayuntamiento De Arona Dña. Eva Luz Cabrera García Concejal de Patrimonio Histórico del Ayuntamiento de Arona Coordinación académica de las jornadas: Dña. Carmen Rosa Pérez Barrios D. Manuel Hernández González Dña. Ana María Quesada Acosta D. Adolfo Arbelo García Coordinación técnica de las jornadas: Dña. Ana Sonia Fernández Alayón © Concejalía de Patrimonio Histórico. Ayuntamiento de Arona EDICIÓN: Llanoazur Ediciones ISBN: 97-84-930898-1-8 DL: TF 217-2015 Índice Manuel Hernández González. Ponencia marco Emigración sureña a Venezuela (1670-1810) .................................... 11 Carlos Perdomo Pérez, Francisco Pérez Caamaño y Javier Soler Segura El patrimonio arqueológico de Arona (Tenerife) ................................. 51 Elisa Álvarez Martín, Leticia García González y Vicente Valencia Afonso El patrimonio etnográfico de Adeje: Aspectos generales .......................... 73 José Antonio González Marrero Las relaciones de parentesco generadas por una familia de esclavos de Arico .................................................................................... 95 José María Mesa Martín El beneficio de Isora, nuevas aportaciones a la administración y jurisdicción religiosa del suroeste de Tenerife: Guía de Isora- Santiago del Teide ...................................................................... -

Revista Por El Ayuntamiento

Nº 3, Julio 2008 www.aytofrontera.org Ayuntamiento de La Frontera - El Hierro EspecialEspecial FiestasFiestas SanSan JuanJuan -- AmadorAmador -- SanSan LorenzoLorenzo -- CandelariaCandelaria Escuela deFinaliza Padres la Acondicionamiento Campanario y Punta Grande Vuelve la Subida a la Cumbre Rehabilitación Calle Tigaday Colegio Tigaday tiene Mascota de la Salud 2 LA FRONTERA > EDICIÓN / SUMARIO Comienza la rehabilitación 5 de la Calle Tigaday Edita: Ayuntamiento de La Frontera C/. La Corredera, 10 Escuela de Padres 38911 Frontera - El Hierro 7 Teléfono: 922 555 999 Fax: 922 555 063 Web: www.aytofrontera.org E-mails: [email protected] Jornada Intercultural [email protected] 9 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Perro Lobo Herreño [email protected] 12 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Bimbache Jazz Festival Coordinación y Redacción: 15 Gabinete de Prensa Ayuntamiento de La Frontera Diseño y Producción: CASA PAPEL - Alexander Geistlinger M.A. DATOS DE LA EDICIÓN DATOS Tfno: 922 555 909 - [email protected] SUMARIO - JULIO 2008 www.elhierroinfo.com 21 Selección de Bola Canaria Fotomecánica e Impresión: Gráfica Abona S.L. - San Isidro - Tenerife Telf: 922 39 16 14 Depósito legal: TF-2318-2007 Agradecemos la colaboración de todas las personas que han hecho posible esta edición. 25 Libro de fotografía antigua Julio 2008 SUMARIO / SALUDA > LA FRONTERA 3 Saluda 6 Visitas Institucionales Construir la identidad del Municipio. Homenaje a Celsa Zamora Una publicación municipal es algo más ejecución y otros finalizados, como es el caso 8 que información, es una herramienta que nos de los deportes o los actos culturales progra- ayuda a construir la identidad del Municipio mados durante estos tres meses. -

Los Germanos En Las Islas Canarias

'FRANZ VON LOEHER LOS GERMANOS ISLAS .CANARIAS .V LO . h e .,,,'::..... C1AL -'lA olU J) ElnlAH IlO HI<; ~ll<;Df NA. EIlITUf{ ";l,11e ¡¡f'lo 1;. (·lll~g'inf,lI. ti LOS GERM ANOS EN LAS ISLAS CANARIAS. LOS GERMANOS EN LAS ISLAS CANARIAS POR FRANZ VON LOEHER MADRID IMPRENTA CENTRAL Á CARGO DE V. SAIZ Calle de la Colegiata. 6 LOS GERMANOS EN LAS ISLAS CANARIAS. 1. Los que visitan por primera vez las islas Cana¡'ias se convencen al poco tiempo de ,que aquella pobla cion se compone de dos razas disLintas, por mas que todos sus habitantes hablen una misma lengua. Los de raza pura española r.esiden, por lo general, en las poblaciones de impOl'Lancia yen las grandes hacien das. 1a gente campesina y la que forma la clase ín• fima del pueblo tienen otra fisonomia, otra confor macion física y hasta costumbres y maneras diferen tes de los oriundos de raza españJla. MI'. Bel'Lhelot, auto¡' de una extensa obra sobre el archipiélago ca llario, en el que residió por espacio de diez años, llegó á familiarizarse de tal modo con aquellas fiso nomías, que pudo reconocerlas más tarde entre los infiniLos pueblos que emigran á diversos puntos'de América. El observador aleman, que desde la costa de Tenerife penetra en el interior del país y en las aldeas, encuentra allí rostros sajones Lan puros como 6 pudiera hallarlos,en las frondosas colinas de West ralia, y su vista despierta en él un sentimiento de afinidad igual al que producen en todo corazon ger mano los Borgoñones hablando frances, los Pensil vanos hablando inglés, y los Zipsers en Hungrla ha blando la lengua magiar. -

Commission of the European Communities

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES c0ll(85) 692 f inaL ,51 tu Brussets, 6 December 19E5 e ProposaI for a COUNCIL REGULATION (EEC) concerni ng the definition of the concept of "originating products" and methods of administrative cooperation in the trade betveen the customs terri tory of the Community, Ceuta and l{eLi[La and the Canary Islands (submitted to the Councit by the Cqnmission) l, COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES cOir(85) 692 finat BrusseLs, 6 December 1985 ProposaL for a COUNCIL REGULATION (EEC) concerning the definition of the concept of "originating products" and methods of administrative cooperation in the trade betreen the customs territory of the Community, Ceuta and ttletiLLa and the Canary Islands (submitted to the CouncjL by the Ccrnmission) COlq(85) 692 finaL EIP'JA}IATORY NOTE According to Protocol no 2 of the Act of adhesion, the Spanish territories of the Canary Islandsr Ceuta and !{elilla are not lncluded in the customs territory of the Comnunityr and their trade nith the latter will beneflt from a reciprocal preferential systen, which wirl end, with duty free entry, with aome exceptions, after the transitional period. Article 9 of the said Protocol provides for the Council to adopt, voting be- fore the lst of Mardr 1986, by qualified majority on a ComissLon proposal, the origin rules to be applied in the trade between these territories and the Comunity. At the adhesion negotiations, the inter-ministeriar conference agrreed on a draft project of origin rules corresponding to those already adopted i-n the Communlty preferential schemes lrith Third Countries. -

Biblioteca Tasdlist

TASDLIST - BIBLIOTECA AMMAS N WARRATN CENTRO DE DOCUMENTACIÓN AMAZIGH TASDLIST – BIBLIOTECA NORMAS DE USO 1. Consulta en Sala. CLASIFICACIÓN DECIMAL UNIVERSAL 0 GENERALIDADES 00 Fundamentos de la ciencia y de la cultura. 01 Bibliografía y bibliografías. Catálogos. 02 Biblioteconomía. Bibliotecología. 030 Obras de referencia general. Enciclopedias. Diccionarios. 050 Publicaciones seriadas y afines. Publicaciones periódicas. 06 Organizaciones y colectividades de cualquier tipo. Asociaciones. Congresos. Exposiciones. Museos. 070 Periódicos. La Prensa. Periodismo. 08 Poligrafías. Colecciones. Series. 09 Manuscritos. Libros raros y notables. 1 FILOSOFÍA 11 Metafísica. 13 Filosofía del espíritu. 14 Sistemas filosóficos. 159.9 Psicología. 16 Lógica. Teoría del conocimiento. Metodología lógica. 17 Moral. Ética. Filosofía práctica. 2 RELIGIÓN. TEOLOGÍA 21 Teología natural. Teodicea. 22 La Biblia. 23/28 Religión cristiana. 23 Teología dogmática. 24 Teología moral. Práctica religiosa. 25 Teología pastoral 26 Iglesia cristiana. 27 Historia general de la iglesia cristiana. 28 Iglesias cristianas. Comunidades y sectas. 29 Religiones no cristianas. Mitología. Cultos. Religión comparada. 291 Ciencia e historia comparada de las religiones. 294 Religiones de la India. 296 Religión judía. 297 El Islam. Mahometismo. 299 Otras religiones 3 CIENCIAS SOCIALES 303 Métodos de las ciencias sociales. 304 Cuestión social en general. 308 Sociografía. Estudios descriptivos. 31 Estadística. Demografía. Sociología. 311 Ciencia estadística. Teoría de la estadística. 314 Demografía. Estudios de población. 314.7 Migración. 316 Sociología. 32 Política. [325] Migración. Colonización. 327 Relaciones políticas internacionales. 33 Economía. Economía política. Ciencia económica. 331 Trabajo. 336 Finanzas. Hacienda pública. Banca. Moneda. 339 Comercio. Relaciones económicas internacionales. Economía mundial. 34 Derecho. 35 Administración pública. 355/359 Arte y ciencia militares. Defensa nacional. -

The Iberian-Guanche Rock Inscriptions at La Palma Is.: All Seven Canary Islands (Spain) Harbour These Scripts

318 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 14, pp: 318 - 336 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i14.5 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Report The Iberian-Guanche rock inscriptions at La Palma Is.: all seven Canary Islands (Spain) harbour these scripts Antonio Arnaiz-Villena1*, Fabio Suárez-Trujillo1, Valentín Ruiz-del-Valle1, Adrián López-Nares1, Felipe Jorge Pais-Pais2 1Department of Inmunology, University Complutense, School of Medicine, Madrid, Spain 2Director of Museo Arqueológico Benahoarita. C/ Adelfas, 3. Los Llanos de Aridane, La Palma, Islas Canarias. *Corresponding author: Antonio Arnaiz-Villena. Departamento de Inmunología, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Complutense, Pabellón 5, planta 4. Avd. Complutense s/n, 28040, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected]; Web page:http://chopo.pntic.mec.es/biolmol/ (Received 15 October 2020; Accepted 5 November 2020; Published 20 November 2020) Abstract - Rock Iberian-Guanche inscriptions have been found in all Canary Islands including La Palma: they consist of incise (with few exceptions) lineal scripts which have been done by using the Iberian semi-syllabary that was used in Iberia and France during the 1st millennium BC until few centuries AD .This confirms First Canarian Inhabitants navigation among Islands. In this paper we analyze three of these rock inscriptions found in westernmost La Palma Island: hypotheses of transcription and translation show that they are short funerary and religious text, like of those found widespread through easternmost Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and also Tenerife Islands. They frequently name “Aka” (dead), “Ama” (mother godness) and “Bake” (peace), and methodology is mostly based in phonology and semantics similarities between Basque language and prehistoric Iberian-Tartessian semi-syllabary transcriptions. -

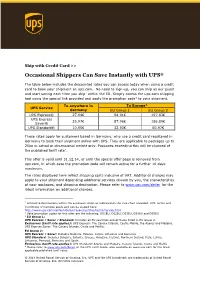

Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS®

Ship with Credit Card >> Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS® The table below includes the discounted rates you can access today when using a credit card to book your shipment on ups.com. No need to sign-up, you can ship as our guest and start saving each time you ship1 within the EU. Simply access the ups.com shipping tool using the special link provided and apply the promotion code2 to your shipment. To anywhere in To Europe3 UPS Service Germany EU Group 1 EU Group 2 UPS Express® 27.94€ 94.01€ 197.83€ UPS Express 25.97€ 87.96€ 186.89€ Saver® UPS Standard® 10.95€ 32.93€ 50.97€ These rates apply for customers based in Germany, who use a credit card registered in Germany to book their shipment online with UPS. They are applicable to packages up to 20kg in actual or dimensional weight only. Packages exceeding this will be charged at the published tariff rate4. This offer is valid until 31.12.14, or until the special offer page is removed from ups.com, in which case the promotion code will remain active for a further 10 days maximum. The rates displayed here reflect shipping costs inclusive of VAT. Additional charges may apply to your shipment depending additional services chosen by you, the characteristics of your packages, and shipping destination. Please refer to www.ups.com/de/en for the latest information on additional charges. 1 Limited to destinations within the European Union as indicated on the rate chart provided. UPS Terms and Conditions of Carriage apply and can be viewed here: http://www.ups.com/content/de/en/resources/ship/terms/service.html 2 Valid promotion codes for this offer are the following: DE1EU, DE2EU, DE3EU, DE4EU and DE5EU 3 EU Group 1: UPS Express / Saver / Standard: Includes all EU countries except those listed in EU Group 2. -

In the Canary Islands: a Prospective Analysis of the Concept of Tricontinentality

The “African being” in the Canary Islands: a prospective analysis of the concept of Tricontinentality José Otero Universidad de La Laguna 2017 1. Introduction Are the Canary Islands considered part of Africa? Instead of answering directly this question, my intervention today - which is a summary of my PhD dissertation- will go over the different responses to that question by local intellectual elites since the conquer and colonization of the Canary Islands. There are certain connections between Africa and the archipelago and I would like to present them from three different perspectives: 1) Understanding the indigenous inhabitant of the Canary Islands as an “African being”. 2) Reconstructing the significance of the Canary Islands in the Atlantic slave trade and its effects on some local artists in the first decades of the twentieth century. 3) Restructuring the interpretation of some Africanity in the cultural and political fields shortly before the end of Franco’s dictatorial regime. 2. The guanches and Africa: the repetition of denial The Canary Islands were inhabited by indigenous who came from North Africa in different immigrant waves –at the earliest– around the IX century B.C. (Farrujía, 2017). The conquest of the Islands by the Crown of Castile was a complex phenomenon and took place during the entire XV century. Knowledge of indigenous cultures has undoubtedly been the main theme of any historical and anthropological reflection made from the archipelago and even today, the circumstances around the guanches provokes discussions and lack of consensus across the social spectrum, not just among academic disciplines but in popular culture too. -

Molina-Et-Al.-Canary-Island-FH-FEM

Forest Ecology and Management 382 (2016) 184–192 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Fire history and management of Pinuscanariensis forests on the western Canary Islands Archipelago, Spain ⇑ Domingo M. Molina-Terrén a, , Danny L. Fry b, Federico F. Grillo c, Adrián Cardil a, Scott L. Stephens b a Department of Crops and Forest Sciences, University of Lleida, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Lleida, Spain b Division of Ecosystem Science, Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, 130 Mulford Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3114, USA c Department of the Environment, Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Gran Canaria, Spain article info abstract Article history: Many studies report the history of fire in pine dominated forests but almost none have occurred on Received 24 May 2016 islands. The endemic Canary Islands pine (Pinuscanariensis C.Sm.), the main forest species of the island Received in revised form 27 September chain, possesses several fire resistant traits, but its historical fire patterns have not been studied. To 2016 understand the historical fire regimes we examined partial cross sections collected from fire-scarred Accepted 2 October 2016 Pinuscanariensis stands on three western islands. Using dendrochronological methods, the fire return interval (ca. 1850–2007) and fire seasonality were summarized. Fire-climate relationships, comparing years with high fire occurrence with tree-ring reconstructed indices of regional climate were also Keywords: explored. Fire was once very frequent early in the tree-ring record, ranging from 2.5 to 4 years between Fire management Fire suppression fires, and because of the low incidence of lightning, this pattern was associated with human land use. -

Canary Islands

CANARY ISLANDS EXP CAT PORT CODE TOUR DESCRIPTIVE Duration Discover Agadir from the Kasbah, an ancient fortress that defended this fantastic city, devastated on two occasions by two earthquakes Today, modern architecture dominates this port city. The vibrant centre is filled with Learn Culture AGADIR AGADIR01 FASCINATING AGADIR restaurants, shops and cafes that will entice you to spend a beautiful day in 4h this eclectic city. Check out sights including the central post office, the new council and the court of justice. During the tour make sure to check out the 'Fantasy' show, a highlight of the Berber lifestyle. This tour takes us to the city of Taroudant, a town noted for the pink-red hue of its earthen walls and embankments. We'll head over by coach from Agadir, seeing the lush citrus groves Sous Valley and discovering the different souks Discover Culture AGADIR AGADIR02 SENSATIONS OF TAROUDANT scattered about the city. Once you have reached the centre of Taroudant, do 5h not miss the Place Alaouine ex Assarag, a perfect place to learn more about the culture of the city and enjoy a splendid afternoon picking up lifelong mementos in their stores. Discover the city of Marrakech through its most emblematic corners, such as the Mosque of Kutubia, where we will make a short stop for photos. Our next stop is the Bahia Palace, in the Andalusian style, which was the residence of the chief vizier of the sultan Moulay El Hassan Ba Ahmed. There we will observe some of his masterpieces representing the Moroccan art. With our Feel Culture AGADIR AGADIR03 WONDERS OF MARRAKECH guides we will have an occasion to know the argan oil - an internationally 11h known and indigenous product of Morocco. -

In Gran Canaria

Go Slow… in Gran Canaria Naturetrek Tour Report 7th – 14th March 2020 Gran Canaria Blue Chaffinch Canary Islands Red Admiral Report & images by Guillermo Bernal Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Go Slow… in Gran Canaria Tour participants: Guillermo Bernal and Maria Belén Hernández (leaders) together with nine Naturetrek clients Summary Gran Canaria may be well-known as a popular sun-seekers’ destination, but it contains so much more, with a wealth of magnificent scenery, fascinating geology and many endemic species or subspecies of flowers, birds and insects. On this, the second ‘Go Slow’ tour, we were able to enjoy some of the best of the island’s rugged volcanic scenery, appreciating the contrasts between the different habitats such as the bird- and flower-rich Laurel forest and the dramatic ravines, and the bare rain-starved slopes of the south. The sunset from the edge of the Big Caldera in the central mountains, the wonderful boat trip, with our close encounters with Atlantic Spotted Dolphins and Cory’s Shearwater, the Gran Canarian Blue Chaffinch and the vagrant Abyssinian Roller, the echoes of past cultures in the caves of Guayadeque, and the beauty of the Botanic Garden with its Giant Lizards were just some of the many highlights. There was also time to relax and enjoy the pools in our delightful hotel overlooking the sea. Good weather with plenty of sunshine, comfortable accommodation, delicious food and great company all made for an excellent week.