In the Canary Islands: a Prospective Analysis of the Concept of Tricontinentality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcripción Del Manuscrito Nº 3

ESTUDIOS HISTÓRICOS, CLIMATOLÓGICOS Y PATOLÓGICOS DE LAS ISLAS CANARIAS GREGORIO CHIL Y NARANJO [Transcripción© El Museo del manuscrito Canario nº 3] Transcripción realizada por: Amara Mª Florido Castro Isabel Saavedra Robaina 2000-2001 1 Manuscrito nº 3 * Índice Libro V 222-224 I - Llegada del general Rejón a Gran Canaria 224-232 II- Batalla del Guiniguada 232-237 III- Llegada a Gran Canaria de don Pedro Fernández de Algaba 237-239 IV- Batalla de Tirajana 239-245 V- Vuelve por tercera vez a Gran Canaria d. Juan Rejón 246-249 VI- Llegada del general d. Pedro de Vera sustituyendo en el mando general de la conquista a d. Juan Rejón 249-255 VII- Batalla de Arucas - Muerte de Doramas - Ataque del Agaete y Tirajana 255-257 VIII- Últimos esfuerzos del guayre Bentaguaya para liberar a Canaria 257-260 IX- Llega Rejón por cuarta vez a Canaria con orden de conquistar a Tenerife y La Palma. Su muerte en La Gomera 260-262 X- Quejas de doña Elvira e Sotomayor a los reyes por el asesinato de su marido el general Rejón y acontecimientos de Hernán Peraza © El Museo Canario 262-266 XI- Estado de Gran Canaria a principios de 1482. Prisión del Guanarteme Tenesor- Semidán 266-268 XII- Estado de Gran Canaria después de la prisión del Guanarteme de Gáldar Tenesor-Semidán llamado el Bueno * En la transcripción ha sido respetada la foliación original. Dicha paginación ha sido indicada a través de un superíndice correspondiente al inicio de cada uno de los folios originales del manuscrito. Asimismo, ha sido respetada la ortografía original. -

Commission of the European Communities

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES c0ll(85) 692 f inaL ,51 tu Brussets, 6 December 19E5 e ProposaI for a COUNCIL REGULATION (EEC) concerni ng the definition of the concept of "originating products" and methods of administrative cooperation in the trade betveen the customs terri tory of the Community, Ceuta and l{eLi[La and the Canary Islands (submitted to the Councit by the Cqnmission) l, COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES cOir(85) 692 finat BrusseLs, 6 December 1985 ProposaL for a COUNCIL REGULATION (EEC) concerning the definition of the concept of "originating products" and methods of administrative cooperation in the trade betreen the customs territory of the Community, Ceuta and ttletiLLa and the Canary Islands (submitted to the CouncjL by the Ccrnmission) COlq(85) 692 finaL EIP'JA}IATORY NOTE According to Protocol no 2 of the Act of adhesion, the Spanish territories of the Canary Islandsr Ceuta and !{elilla are not lncluded in the customs territory of the Comnunityr and their trade nith the latter will beneflt from a reciprocal preferential systen, which wirl end, with duty free entry, with aome exceptions, after the transitional period. Article 9 of the said Protocol provides for the Council to adopt, voting be- fore the lst of Mardr 1986, by qualified majority on a ComissLon proposal, the origin rules to be applied in the trade between these territories and the Comunity. At the adhesion negotiations, the inter-ministeriar conference agrreed on a draft project of origin rules corresponding to those already adopted i-n the Communlty preferential schemes lrith Third Countries. -

Guía Museos De Canarias

GUÍA DE MUSEOS Y ESPACIOS CULTURALES DE CANARIAS GUÍA DE MUSEOS Y ESPACIOS CULTURALES DE CANARIAS GUÍA DE MUSEOS Y ESPACIOS CULTURALES DE CANARIAS Presidente del Gobierno de Canarias Fernando Clavijo Batlle Consejero de Turismo, Cultura y Deportes Isaac Castellano San Ginés Viceconsejero de Cultura y Deportes Aurelio González González Director General de Patrimonio Cultural Miguel Ángel Clavijo Redondo Jefe de Servicio José Carlos Hernández Santana Técnicos Eliseo G. Izquierdo Rodríguez Christian J. Perazzone Diseño, maquetación y corrección de estilo PSJM Fotografías © de los museos y espacios culturales © pp. 206-207: Jason deCaires Taylor / CACT Lanzarote © pp. 242-243: Loli Gaspar © pp. 300-301: artemarfotografía Impresión Estugraf Impresores, S.L. Guía de Museos y Espacios Culturales de Canarias ISBN: 978-84-7947-675-5 [Las Palmas de Gran Canaria; Santa Cruz de Tenerife]: Dep. Legal: GC 711-2017 332 p. 660 il. col. 19,5 x 14,5 cm D.L. GC 711-2017 ISBN 978-84-7947-675-5 © Presentación Canarias puede sentirse orgullosa de contar con un patrimonio cultural único y excepcional. Muestra de esta riqueza y variedad la atesoran nuestros museos. Hace años que estos templos del saber, la cultura, la historia y la sensibilidad artística dejaron de ser un re- ducto minoritario y, hoy, realizar una visita a cualquier museo se va convirtiendo en una alternativa lúdica para el tiempo de ocio de muchos ciudadanos. Templos, como gustaba escribir a los ilustrados, de la historia puestos al servicio de la sociedad y de su de- sarrollo; conservan, investigan, difunden y exponen los testimonios materiales del hombre y su entorno con el objetivo último de educar y deleitar en espacios siem- Fernando Estévez González pre abiertos a la imaginación e imaginarios. -

Gran Canaria Es Uno De Los Mayores Emporios Turísticos De España

Gran Canaria es uno de los mayores emporios turísticos de España porque ofrece mucho y todo bueno: diversidad de paisajes, pueblos recoletos, cráteres volcánicos y dunas solitarias. Gran Canaria es una de las siete islas que conforman el archipiélago canario, situado a tan solo 100 km del continente africano en su punto más próximo y con un 43 por ciento de su territorio declarado Reserva de la Biosfera por la Unesco. Tiene forma casi circular y una superficie de 1.532 km2, con 47 kilómetros de anchura y 55 de longitud. La orografía de la isla se caracteriza por profundos barrancos que convergen en el centro, donde se encuentra el punto más alto, el Pico de las Nieves, de 1.950 metros. Gran Canaria cuenta con 236 km de costa jalonada con numerosas playas arenosas de gran extensión y belleza. Las Palmas La vida artística y cultural de Gran Canaria se centra principalmente en su capital, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, donde se encuentran numerosos museos, teatros, centros culturales, salas de exposiciones y de cine, etc. En el histórico barrio de Vegueta puede visitarse el Museo Canario, que acoge un importante material arqueológico y documental de las culturas prehispánicas; la Casa de Colón, con diversas salas de exposición, una biblioteca y un centro de estudios especializado, la ermita de San Antonio Abad, la catedral de Santa Ana y el Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, una de las salas más vanguardistas e interesantes del panorama artístico nacional. Antes de abandonar el barrio de Vegueta, no está de más visitar el teatro Guiniguada o darse una vuelta por el mercado, fechado en 1854. -

Mexico and Spain on the Eve of Encounter

4 Mexico and Spain on the Eve of Encounter In comparative history, the challenge is to identify significant factors and the ways in which they are related to observed outcomes. A willingness to draw on historical data from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean will be essen- tial in meeting this challenge. — Walter Scheidel (2016)1 uring the decade before Spain’s 1492 dynastic merger and launching of Dtrans- Atlantic expeditions, both the Aztec Triple Alliance and the joint kingdoms of Castile and Aragón were expanding their domains through con- quest. During the 1480s, the Aztec Empire gained its farthest flung province in the Soconusco region, located over 500 miles (800 km) from the Basin of Mexico near the current border between Mexico and Guatemala. It was brought into the imperial domain of the Triple Alliance by the Great Speaker Ahuitzotl, who ruled from Tenochtitlan, and his younger ally and son- in- law Nezahualpilli, of Texcoco. At the same time in Spain, the allied Catholic Monarchs Isabela of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragón were busy with military campaigns against the southern emirate of Granada, situated nearly the same distance from the Castilian heartland as was the Soconusco from the Aztec heartland. The unification of the kingdoms ruled by Isabela and Ferdinand was in some sense akin to the reunifi- cation of Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior of the early Roman period.2 The conquest states of Aztec period Mexico and early modern Spain were the product of myriad, layered cultural and historical processes and exchanges. Both were, of course, ignorant of one another, but the preceding millennia of societal developments in Mesoamerica and Iberia set the stage for their momentous en- counter of the sixteenth century. -

Monumento Natural Del Barranco De Guayadeque

CA LI ÚB Plan Rector de Uso y Gestión P Plan Especial Prot. Paisajística N IÓ Normas de Conservación AC Plan Especial de Protección Paisajística M R Plan Director FO Color reserva natural especial [en pantone machine system PANTONE 347 CV] IN Color para parques naturales [ PANTONE 116 CV ] Color gris de fondo [Modelo RGB: R - 229,G - 229, B - 229] GOBIERNO DE CANARIAS OSS N CONSEJERÍA DE MEDIO AMBIENTE Y CCO IÓ ORDENACIÓN TERRITORIAL TII AC VICECONSEJERÍA DE ÁÁT M A ORDENACIÓN TERRITORIAL MM R IC DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE ORDENACIÓN EE FO L DEL TERRITORIO TT N B I PÚ JJOO Normas de Conservación AA AABB TTRR NN IMonumentoÓÓ Natural CCI del AABarranco de Guayadeque CCEE BB AANN OO AAVV PPRR AA Parque Rural Parque Rural Parque Natural Parque Natural Reserva Natural Integral Reserva Natural Integral A Reserva Natural Especial Reserva Natural Especial A Sendero IIVV Sendero IITT Paisaje Protegido Paisaje Protegido IINN Monumento Natural Monumento Natural FF Sitio de Interés Científico Sitio de Interés Científico DDEE Memoria Informativa Monumento Natural Normas de Barranco de Guayadeque Conservación ÍNDICE GENERAL. TOMO I EQUIPO REDACTOR ........................................................................................ 2 FUENTES CONSULTADAS............................................................................... 3 INDICE DE PLANOS ......................................................................................... 5 MEMORIA INFORMATIVA................................................................................. 6 Rabadán 17, -

The Iberian-Guanche Rock Inscriptions at La Palma Is.: All Seven Canary Islands (Spain) Harbour These Scripts

318 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 14, pp: 318 - 336 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i14.5 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Report The Iberian-Guanche rock inscriptions at La Palma Is.: all seven Canary Islands (Spain) harbour these scripts Antonio Arnaiz-Villena1*, Fabio Suárez-Trujillo1, Valentín Ruiz-del-Valle1, Adrián López-Nares1, Felipe Jorge Pais-Pais2 1Department of Inmunology, University Complutense, School of Medicine, Madrid, Spain 2Director of Museo Arqueológico Benahoarita. C/ Adelfas, 3. Los Llanos de Aridane, La Palma, Islas Canarias. *Corresponding author: Antonio Arnaiz-Villena. Departamento de Inmunología, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Complutense, Pabellón 5, planta 4. Avd. Complutense s/n, 28040, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected]; Web page:http://chopo.pntic.mec.es/biolmol/ (Received 15 October 2020; Accepted 5 November 2020; Published 20 November 2020) Abstract - Rock Iberian-Guanche inscriptions have been found in all Canary Islands including La Palma: they consist of incise (with few exceptions) lineal scripts which have been done by using the Iberian semi-syllabary that was used in Iberia and France during the 1st millennium BC until few centuries AD .This confirms First Canarian Inhabitants navigation among Islands. In this paper we analyze three of these rock inscriptions found in westernmost La Palma Island: hypotheses of transcription and translation show that they are short funerary and religious text, like of those found widespread through easternmost Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and also Tenerife Islands. They frequently name “Aka” (dead), “Ama” (mother godness) and “Bake” (peace), and methodology is mostly based in phonology and semantics similarities between Basque language and prehistoric Iberian-Tartessian semi-syllabary transcriptions. -

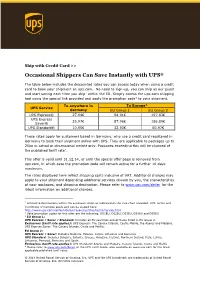

Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS®

Ship with Credit Card >> Occasional Shippers Can Save Instantly with UPS® The table below includes the discounted rates you can access today when using a credit card to book your shipment on ups.com. No need to sign-up, you can ship as our guest and start saving each time you ship1 within the EU. Simply access the ups.com shipping tool using the special link provided and apply the promotion code2 to your shipment. To anywhere in To Europe3 UPS Service Germany EU Group 1 EU Group 2 UPS Express® 27.94€ 94.01€ 197.83€ UPS Express 25.97€ 87.96€ 186.89€ Saver® UPS Standard® 10.95€ 32.93€ 50.97€ These rates apply for customers based in Germany, who use a credit card registered in Germany to book their shipment online with UPS. They are applicable to packages up to 20kg in actual or dimensional weight only. Packages exceeding this will be charged at the published tariff rate4. This offer is valid until 31.12.14, or until the special offer page is removed from ups.com, in which case the promotion code will remain active for a further 10 days maximum. The rates displayed here reflect shipping costs inclusive of VAT. Additional charges may apply to your shipment depending additional services chosen by you, the characteristics of your packages, and shipping destination. Please refer to www.ups.com/de/en for the latest information on additional charges. 1 Limited to destinations within the European Union as indicated on the rate chart provided. UPS Terms and Conditions of Carriage apply and can be viewed here: http://www.ups.com/content/de/en/resources/ship/terms/service.html 2 Valid promotion codes for this offer are the following: DE1EU, DE2EU, DE3EU, DE4EU and DE5EU 3 EU Group 1: UPS Express / Saver / Standard: Includes all EU countries except those listed in EU Group 2. -

Lo Canario, Lo Guanche Y Lo Prehispánico

UNIVERSIDAD OE L» LAGUNA BIBLIOTECA Foll. 27 S»-va.t3lica,eloiies <±m la. ^isa.1 Sooied.a.d. C3-eog^rá,íxca, Serle B Número 387 Lo canario, lo panche y lo pretiispánico POR Sebastián Jiménez Sánchez Académico Correspondiente de la Real de la Historia M ADKID S|. AüUlRRE TORRE, IMPRESOR Calle de! Gral. Alvarez de Castro, 38 1 » í 7 ^ .^ ¿^ Lo canario, lo guanche y lo prehispánico SEBASTIAN JIMÉNEZ SÁNCHEZ Académico Correspondiente de la Real de la Historia Desde hace tiempo se viene dando impropiamente el nombre de guanches a los habitantes primitivos de las Islas Canarias, en su épo ca prehispánica, y con él a todo el exponente de su cultura milenaria, material y espiritual. Porque estimamos necesario aclarar el uso in correcto del nombre guanche, empleado por algunos escritores e in vestigadores, escribimos estas líneas para más ahondar en el tema y dar luces sobre el mismo. La palabra' guanche, ya considerada como nombre sustantivo o como nombre adjetivo, tiene especialísima significación, limitada sólo a los habitantes y a la cultura de la isla de Tenerife en su período preüispánico, aunque erróneamente literatos y ciertos investigadores no bien formados en los problemas canarios, especialmente extran jeros, hayan querido encontrar en la voz y grafía guanche el nom bre genérico que conviene y agrupa a los primitivos habitantes del archipiélago canario. El pretender emplear la palabra guanche en tal sentido está en pugna con el rigorismo histórico y con el proceso racial de las Islas, como fruto de las oleadas y de los cruces de remotos pueblos invasores. -

Molina-Et-Al.-Canary-Island-FH-FEM

Forest Ecology and Management 382 (2016) 184–192 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Fire history and management of Pinuscanariensis forests on the western Canary Islands Archipelago, Spain ⇑ Domingo M. Molina-Terrén a, , Danny L. Fry b, Federico F. Grillo c, Adrián Cardil a, Scott L. Stephens b a Department of Crops and Forest Sciences, University of Lleida, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Lleida, Spain b Division of Ecosystem Science, Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, 130 Mulford Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3114, USA c Department of the Environment, Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Av. Rovira Roure 191, 25198 Gran Canaria, Spain article info abstract Article history: Many studies report the history of fire in pine dominated forests but almost none have occurred on Received 24 May 2016 islands. The endemic Canary Islands pine (Pinuscanariensis C.Sm.), the main forest species of the island Received in revised form 27 September chain, possesses several fire resistant traits, but its historical fire patterns have not been studied. To 2016 understand the historical fire regimes we examined partial cross sections collected from fire-scarred Accepted 2 October 2016 Pinuscanariensis stands on three western islands. Using dendrochronological methods, the fire return interval (ca. 1850–2007) and fire seasonality were summarized. Fire-climate relationships, comparing years with high fire occurrence with tree-ring reconstructed indices of regional climate were also Keywords: explored. Fire was once very frequent early in the tree-ring record, ranging from 2.5 to 4 years between Fire management Fire suppression fires, and because of the low incidence of lightning, this pattern was associated with human land use. -

Canary Islands

CANARY ISLANDS EXP CAT PORT CODE TOUR DESCRIPTIVE Duration Discover Agadir from the Kasbah, an ancient fortress that defended this fantastic city, devastated on two occasions by two earthquakes Today, modern architecture dominates this port city. The vibrant centre is filled with Learn Culture AGADIR AGADIR01 FASCINATING AGADIR restaurants, shops and cafes that will entice you to spend a beautiful day in 4h this eclectic city. Check out sights including the central post office, the new council and the court of justice. During the tour make sure to check out the 'Fantasy' show, a highlight of the Berber lifestyle. This tour takes us to the city of Taroudant, a town noted for the pink-red hue of its earthen walls and embankments. We'll head over by coach from Agadir, seeing the lush citrus groves Sous Valley and discovering the different souks Discover Culture AGADIR AGADIR02 SENSATIONS OF TAROUDANT scattered about the city. Once you have reached the centre of Taroudant, do 5h not miss the Place Alaouine ex Assarag, a perfect place to learn more about the culture of the city and enjoy a splendid afternoon picking up lifelong mementos in their stores. Discover the city of Marrakech through its most emblematic corners, such as the Mosque of Kutubia, where we will make a short stop for photos. Our next stop is the Bahia Palace, in the Andalusian style, which was the residence of the chief vizier of the sultan Moulay El Hassan Ba Ahmed. There we will observe some of his masterpieces representing the Moroccan art. With our Feel Culture AGADIR AGADIR03 WONDERS OF MARRAKECH guides we will have an occasion to know the argan oil - an internationally 11h known and indigenous product of Morocco. -

In Gran Canaria

Go Slow… in Gran Canaria Naturetrek Tour Report 7th – 14th March 2020 Gran Canaria Blue Chaffinch Canary Islands Red Admiral Report & images by Guillermo Bernal Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Go Slow… in Gran Canaria Tour participants: Guillermo Bernal and Maria Belén Hernández (leaders) together with nine Naturetrek clients Summary Gran Canaria may be well-known as a popular sun-seekers’ destination, but it contains so much more, with a wealth of magnificent scenery, fascinating geology and many endemic species or subspecies of flowers, birds and insects. On this, the second ‘Go Slow’ tour, we were able to enjoy some of the best of the island’s rugged volcanic scenery, appreciating the contrasts between the different habitats such as the bird- and flower-rich Laurel forest and the dramatic ravines, and the bare rain-starved slopes of the south. The sunset from the edge of the Big Caldera in the central mountains, the wonderful boat trip, with our close encounters with Atlantic Spotted Dolphins and Cory’s Shearwater, the Gran Canarian Blue Chaffinch and the vagrant Abyssinian Roller, the echoes of past cultures in the caves of Guayadeque, and the beauty of the Botanic Garden with its Giant Lizards were just some of the many highlights. There was also time to relax and enjoy the pools in our delightful hotel overlooking the sea. Good weather with plenty of sunshine, comfortable accommodation, delicious food and great company all made for an excellent week.