A Comparative Study of Primary/ Elementary School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

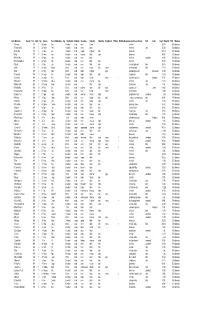

Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First Name Surname

To find your name, click 'ctrl' + 'F' and type your surname. If you entered after 20/02/20 you will not appear on this list, an updated version will be put online on or around the 28/02/20. Runners cannot move into an earlier wave, but you are welcome to move back to a later wave. You do NOT need to inform us of your decision to do this. If you have any problems, please get in touch by phoning 01522 699950. COLOUR RACE APPROX TO THE START WAVE NO. START TIME 1 BLUE A 09:10 2 RED A 09:10 3 PINK A 09:15 4 GREEN A 09:20 5 BLUE B 09:32 6 RED B 09:36 7 PINK B 09:40 8 GREEN B 09:44 9 BLUE C 09:48 10 RED C 09:52 11 PINK C 09:56 12 GREEN C 10:00 VIP BLACK Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First name Surname 11 Pink 1889 Rebecca Aarons Any Black 1890 Jakob Abada 2 Red 4 Susannah Abayomi 3 Pink 1891 Yassen Abbas 6 Red 1892 Nick Abbey 10 Red 1823 Hannah Abblitt 10 Red 1893 Clare Abbott 4 Green 1894 Jon Abbott 8 Green 1895 Jonny Abbott 12 Green 11043 Pamela Abbott 6 Red 11044 Rebecca Abbott 11 Pink 1896 Leanne Abbott-Jones 9 Blue 1897 Emilie Abby Any Black 1898 Jennifer Abecina 6 Red 1899 Philip Abel 7 Pink 1900 Jon Abell 10 Red 600 Kirsty Aberdein 6 Red 11045 Andrew Abery Any Black 1901 Erwann ABIVEN 11 Pink 1902 marie joan ablat 8 Green 1903 Teresa Ablewhite 9 Blue 1904 Ahid Abood 6 Red 1905 Alvin Abraham 9 Blue 1906 Deborah Abraham 6 Red 1907 Sophie Abraham 1 Blue 11046 Mitchell Abrams 4 Green 1908 David Abreu 11 Pink 11047 Kathleen Abuda 10 Red 11048 Annalisa Accascina 4 Green 1909 Luis Acedo 10 Red 11049 Vikas Acharya 11 Pink 11050 Catriona Ackermann -

Listado De Personas Admitidas

PRUEBA PARA LA ELABORACIÓN DE LISTAS DE CONTRATACIÓN TEMPORAL DE ESPECIALISTA DE APOYO EDUCATIVO A través de una prueba selectiva, se constituirán dos relaciones de aspirantes, una en castellano y otra en euskera, para optar a puestos de Especialista de Apoyo Educativo en centros educativos, dependientes del Departamento de Educación. ASISTENCIA A LA PRUEBA. ELECCIÓN DE ZONAS Y JORNADA Las personas que aparecen en el listado facilitado por el SNE, deberán cumplimentar un formulario disponible, a través del botón “Tramitar” en el siguiente enlace para indicar tres aspectos obligatorios para la gestión de las personas aspirantes: 1. Confirmar su asistencia el día de la prueba. 2. Seleccionar las zonas en la que se quiere figurar para las ofertas de contratación. 3. Indicar el tipo de jornada por la que se quiere optar para las ofertas de contratación. El plazo para enviar el formulario cumplimentado, es de diez días hábiles, del 23 de febrero al 8 de marzo de 2021, ambos incluidos. FECHA DE REALIZACIÓN DE LA PRUEBA La prueba se celebrará en Pamplona el sábado 27 de marzo de 2021, por la mañana. Por la situación sanitaria actual debido a la COVID-19, una vez se conozca el número de personas que confirmen su asistencia el día de la prueba, se publicará el lugar de realización de la misma y el protocolo a seguir para cumplir con todas las normas sanitarias establecidas. HEZKUNTZA-LAGUNTZAKO ESPEZIALISTAK ALDI BATERAKO KONTRATATZEKO ZERRENDAK EGITEKO PROBA Hautaproba baten bidez, izangaien bi zerrenda eratuko dira, bata gaztelaniaz eta bestea euskaraz, Hezkuntza Sailaren mendeko ikastetxeetan Hezkuntza Laguntzako Espezialista lanpostuak lortzeko. -

Family Group Sheets Surname Index

PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS SURNAME INDEX This collection of 660 folders contains over 50,000 family group sheets of families that resided in Passaic and Bergen Counties. These sheets were prepared by volunteers using the Societies various collections of church, ceme tery and bible records as well as city directo ries, county history books, newspaper abstracts and the Mattie Bowman manuscript collection. Example of a typical Family Group Sheet from the collection. PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS — SURNAME INDEX A Aldous Anderson Arndt Aartse Aldrich Anderton Arnot Abbott Alenson Andolina Aronsohn Abeel Alesbrook Andreasen Arquhart Abel Alesso Andrews Arrayo Aber Alexander Andriesse (see Anderson) Arrowsmith Abers Alexandra Andruss Arthur Abildgaard Alfano Angell Arthurs Abraham Alje (see Alyea) Anger Aruesman Abrams Aljea (see Alyea) Angland Asbell Abrash Alji (see Alyea) Angle Ash Ack Allabough Anglehart Ashbee Acker Allee Anglin Ashbey Ackerman Allen Angotti Ashe Ackerson Allenan Angus Ashfield Ackert Aller Annan Ashley Acton Allerman Anners Ashman Adair Allibone Anness Ashton Adams Alliegro Annin Ashworth Adamson Allington Anson Asper Adcroft Alliot Anthony Aspinwall Addy Allison Anton Astin Adelman Allman Antoniou Astley Adolf Allmen Apel Astwood Adrian Allyton Appel Atchison Aesben Almgren Apple Ateroft Agar Almond Applebee Atha Ager Alois Applegate Atherly Agnew Alpart Appleton Atherson Ahnert Alper Apsley Atherton Aiken Alsheimer Arbuthnot Atkins Aikman Alterman Archbold Atkinson Aimone -

1980 Surname

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Abbett Howard 91 6-Jan D-2 Abercrombie Levi Sr. 30-Mar E-15 Able Cora Ree 73 4-Dec C-8 Acevedo Marcelina P. 68 11-Dec D-2 Acton John Wesley 85 12-May D-1 Adam Michael Sr. 88 7-Mar B-3 Adam Millee 59 3-Mar B-6 Adam Sophie (Sister Ann 66 15-Dec B-7 Madeline) Adamczyk Josephine 82 4-May D-6 Adams Francis (Sheik) 78 14-Jul C-5 Adams Ruth Carol 41 17-Oct C-5 Adams William H. 63 21-Aug B-2 Ade Eleanor Anne 63 17-Jul C-14 Adelsperger James F. 78 22-Dec C-5 Adkins Otis C. 67 24-Jun C-1 Adler Florian F. 83 10-Aug D-2 Afflek Day Malo 18-Mar B-4 Agosto Gregorio 56 3-Dec E-2 Ahlborn Rudolph C. 81 10-Sep E-1 Ahlborn Walter W. 78 20-Jul D-1 Aikman Myrtle M. 74 26-Nov D-1 Albert Joseph (Larry) 51 11-Jan B-4 Albertson Russell A. 83 27-Jul C-7 Alderden Gertrude 76 7-Jul B-4 Aleman Sadie 21-Jan B-5 Alexander Edward L. 46 5-Aug C-3 Alexander Robert W. Jr. 65 2-Jan C-9 Alexander Sonja E. 67 11-Feb C-4 Alier Audra 65 30-Nov E-11 Brown Allen Clarence F. 57 9-May B-5 Allen Norman 79 7-Aug C-4 Picture included. Allen Rabe (Ray) 95 22-Dec C-5 Allen William J. -

Xerox University Microfilms

information t o u s e r s This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of usefs indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? a Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination

Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination By MARIANNE BERTRAND AND SENDHIL MULLAINATHAN* We study race in the labor market by sending fictitious resumes to help-wanted ads in Boston and Chicago newspapers. To manipulate perceived race, resumes are randomly assigned African-American- or White-sounding names. White names receive 50 percent more callbacks for interviews. Callbacks are also more respon- sive to resume quality for White names than for African-American ones. The racial gap is uniform across occupation, industry, and employer size. We also find little evidence that employers are inferring social class from the names. Differential treatment by race still appears to still be prominent in the U.S. labor market. (JEL J71, J64). Every measure of economic success reveals dates, employers might favor the African- significant racial inequality in the U.S. labor American one.1 Data limitations make it market. Compared to Whites, African-Ameri- difficult to empirically test these views. Since cans are twice as likely to be unemployed and researchers possess far less data than employers earn nearly 25 percent less when they are em- do, White and African-American workers that ployed (Council of Economic Advisers, 1998). appear similar to researchers may look very This inequality has sparked a debate as to different to employers. So any racial difference whether employers treat members of different in labor market outcomes could just as easily be races differentially. When faced with observ- attributed to differences that are observable to ably similar African-American and White ap- employers but unobservable to researchers. -

BB Surname Index

SURNAME Volume No. Page(s) Aamoth 42 3 28 Abbey 45 1 19 Abbey 45 2 25 Abbey 53 1 34 Abbot 42 2 19 Abbott 37 4 4 Abbott 38 4 11, 12 Abbott 49 3 29 Abbott 50 3 25 Abernathy 41 1 8 Abernathy 47 4 19 Abernethy 42 3 21, 22 Abernethy 44 1 29 Abernethy 51 2 42 Abington 39 2 6 Abraham 45 4 30 Abraham 50 4 14 Abram 43 1 22 Abrams 41 1 3 Abrams 47 1 3 Aby 53 1 8 Accerman 52 4 2 Accolti 51 1 31 Acerman 52 4 2 Acetlie 37 1 22 Acherman 52 4 2 Achor 40 2 9 Acker 48 3 8 Ackerman 44 1 2 Ackerman 44 3 5 Ackerman 49 2 36 Ackerman 52 4 2 Ackermen 52 4 2 Ackermin 52 4 2 Ackkermann 52 4 2 Ackley 49 1 31 Ackroyd 47 1 22 Acloa 41 3 28 Acotty 52 2 30 Acraman 52 4 2 Acreman 52 4 2 Acremen 52 4 2 Adair 39 2 16, 17 Adair 43 2 24 Adair 46 2 20 SURNAME Volume No. Page(s) Adair 46 3 19, 20 Adair 46 4 24 Adair 49 1 28 Adam 51 4 8 Adams 37 2 22 Adams 37 3 14, 19 Adams 38 3 4 Adams 39 2 6, 24 Adams 40 1 4, 21 Adams 42 2 21, 23 Adams 42 4 4, 23 Adams 43 1 18-20 Adams 43 3 15 Adams 43 4 24, 25 Adams 44 1 14, 32 Adams 44 4 4, 18, 22 Adams 45 1 12 Adams 45 2 14 Adams 46 2 22 Adams 46 3 20 Adams 46 4 24 Adams 48 3 6, 17 Adams 48 4 4 Adams 49 2 35, 38 Adams 49 3 27, 28, 29 Adams 50 3 33 Adams 51 4 34 Adams 52 3 36 Adams 52 4 2 Adams 53 1 33, 34 Adams 53 3 16, 18, 23 Adamson 39 1 26 Adamson 39 4 24 Adamson 48 3 6 Addison 43 2 9 Adison 39 2 17 Adkins 44 3 26 Adkins 48 4 26 Adkins 51 4 3 Adolph 38 1 4 Adolph 43 1 21 Adolph 45 3 30 Adolph 47 3 3 Adolph 48 4 26 Adolph 49 1 28 SURNAME Volume No. -

E O Card# Mine Name Operator Year Month Day Surname First And

Card# Mine Name Operator Year Month Day Surname First and Middle Name Age Fatal/Nonfatal In/Outside Occupation Nationality Citizen/Alien Single/Married #Children Mine ExpeOccupatio Accident Cause or Remarks Fault County Page# Mining Dist. Film# Bituminous 67 Kennedy 1917 7 25 Fabalak Andy 44 nonfatal inside miner Russian fall of roof 226 27th 3595 bituminous 27 Sonman Shaft 1908 5 26 Fabeze Peter 18 nonfatal inside miner Italian fall of coal victim 105 10th 3594 bituminous 92 Vesta No.4 1917 6 8 Fabian Alex 19 nonfatal inside snapper Hungarian alien by mine cars 202 21st 3595 bituminous 160 Kyle 1917 11 23 Fabian Andy 51 nonfatal inside trackman Slavic citizen by mine cars 140 5th 3595 bituminous 49 Rich Hill No.2 1907 9 20 Fabian John 16 nonfatal inside miner Slavic fall of coal unavoidable 49 15th 3594 bituminous 45 Pennsylvania No.9 1917 4 24 Fabian Sala 44 nonfatal inside miner Polish alien fall of coal 157 10th 3595 bituminous 27 Euclid 1910 5 23 Fabin John 19 nonfatal inside miner Polish alien fall of slate pillar work victim 258 13th 3594 bituminous 44 Hida 1911 8 26 Fabrick Thomas 26 fatal inside miner Horwat alien married fall of roof at entry victim 37 11th 3594 bituminous 166 Darr 1907 12 19 Fabroy Balos 49 fatal inside loader Hungarian single explosion of gas & dust Westmoreland 66 19th 3594 bituminous 73 Vesta No.4 1914 9 14 Fabyan Alex 20 nonfatal inside loader Slavic alien injured by cars victim 78 21st 3595 bituminous 38 Cincinnati 1913 4 23 Fabyan Matt 37 fatal inside loader Austrian married 4 explosion of gas & dust Washington -

Free Tips for Searching Ancestors' Surnames

SURNAMES: FAMILY SEARCH TIPS AND SURNAME ORIGINS Picking a name Naming practices developed differently from region to region and country to country. Yet even today, hereditary The Name Game names tend to fall into one of four categories: patronymic Onomastics, a field of linguistics, is the study of names and (named from the father), occupational, nickname or place naming practices. The American Name Society (ANS) was name. According to Elsdon Smith, author of American Sur- founded in 1951 to promote this field in the United States and names (Genealogical Publishing Co.), a survey of some 7,000 abroad. Its goal is to “find out what really is in a name, and to surnames in America revealed that slightly more than 43 investigate cultural insights, settlement history and linguistic percent of our names derive from places, followed by about characteristics revealed in names.” 32 percent from patronymics, 15 percent from occupations The society publishes NAMES: A Journal of Onomastics, and 9 percent from nicknames. a quarterly journal; the ANS Bulletin; and the Ehrensperger Often the lines blur between the categories. Take the Report, an annual overview of member activities in example of Green. This name could come from one’s clothing onomastics. The society also offers an online discussion or it could be given to one who was inexperienced. It could group, ANS-L. For more information, visit the ANS website at also mean a dweller near the village green, be a shortened <www.wtsn.binghamton.edu/ANS>. form of a longer Jewish or German name, or be a translation from another language. -

ELI Fellows by Surname

ELI Fellows by Surname Surname: First Name(s): Country: Abatangelo Chiara Italy Abbiati Paul Portugal Åbjörnsson Rolf Sweden Abreu Joana Portugal Abu Awwad Amal Italy Achache Florence France Adame Martínez Miguel Ángel Spain Addante Adriana Italy Adler Peter H. Austria Afanasyeva Ekaterina Russia Afferni Giorgio Italy Agudo Gonzalez Jorge Spain Aguilera Marien Spain Ahrens Hans-Jürgen Germany Aichberger Beig Daphne Austria Aimo Mariapaola Italy Akkermans Bram Netherlands Akseli N. Orkun United Kingdom Alba Fernandez Manuel Spain Albert Maria Rosario Spain Alberti Lucia Giuseppina Italy Alemanno Alberto France Alexandropoulou Antigoni Cyprus Alexandru Aurelian Chirita Romania Alexe Alina Romania Allemeersch Benoît Belgium Aloj Nicoletta Italy Alonso Landeta Gabriel Spain Alonso Perez Mª Teresa Spain Alpa Guido Italy Alunaru Christian Romania Amin-Mannion Rosy United Kingdom Amodio Claudia Italy Amtenbrink Fabian Netherlands Anagnostopoulos Ilias Greece Anagnostopoulou Despoina Greece Anches Diana-Ionela Romania Andenas Mads Norway Anderson Ross United Kingdom Andrews Neil United Kingdom Androulakis Ioannis Greece Anker-Sørensen Linn Norway Annoni Alessandra Italy Anthimos Apostolos Greece Antoniolli Luisa Italy Appert Geraldine United Kingdom Arabadjiev Alexander Luxembourg Aran Latif Cyprus Arastey Maria Lourdes Spain Armeli Beatrice Italy Armenta Deu Teresa Spain Armstrong Kenneth United Kingdom Arnold Rainer Germany Arroyo Tatiana Spain Arroyo Amayuelas Esther Spain Atamer Yesim M. Turkish Republic Aubert de Vincelles Carole France -

Functional and Structural Insights Into Glycoside Hydrolase Family 130 Enzymes: Implications in Carbohydrate Foraging by Human Gut Bacteria

TTHHÈÈSSEE En vue de l'obtention du DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE TOULOUSE Délivré par Discipline ou spécialité : Ingénieries Moléculaires et Enzymatiques Présentée et soutenue par Le Titre : JURY Ecole doctorale : Sciences Ecologiques, Vétérinaires, Agronomiques et Bioingénieries (SEVAB) Unité de recherche : LISBP, UMR CNRS 5504, UMR INRA 792, INSA Toulouse Directeur(s) de Thèse : Gabrielle POTOCKI-VÉRONÈSE, Directrice de Recherche INRA Elisabeth LAVILLE, Chargée de Recherche INRA THÈSE En vue de l’obtention du DOCTORAT de L’INSTITUT NATIONAL DES SCIENCES APPLIQUÉES DE TOULOUSE Présentée et soutenue publiquement le mardi 28 avril 2015 Spécialité : Sciences Ecologiques, Vétérinaires, Agronomiques et Bioingénieries Filière : Ingénieries Microbienne et Enzymatique Par Simon LADEVÈZE Functional and Structural insights into glycoside hydrolase family 130 enzymes: implications in carbohydrate foraging by human gut bacteria Directrices de thèse: Mme Gabrielle POTOCKI-VÉRONÈSE, Directrice de Recherche INRA Mme Elisabeth LAVILLE, Chargée de Recherche INRA 1 2 NOM: LADEVÈZE PRÉNOM: Simon TITRE: Apports Fonctionnels et Structuraux à la famille des glycoside hydrolase 130: implications dans la dégradation des glycanes par les bactéries de l'intestin humain. SPÉCIALITÉ: Sciences Ecologiques, Vétérinaires, Agronomiques et Bioingénieries FILIÈRE: Ingénieries Moléculaires et Enzymatiques ANNÉE: 2015 LIEU: INSA, TOULOUSE DIRECTRICES DE THÈSE: Mmes Gabrielle POTOCKI-VÉRONÈSE et Elisabeth LAVILLE RÉSUMÉ: Les relations entre bactéries intestinales, aliments et hôte jouent un rôle crucial dans le maintien de la santé humaine. La caractérisation fonctionnelle d’Uhgb_MP, une enzyme de la famille 130 des glycoside hydrolases découverte par métagénomique fonctionnelle, a révélé une nouvelle fonction de dégradation par phosphorolyse des polysaccharides de la paroi végétale et des glycanes de l'hôte tapissant l'épithélium intestinal. -

Omics, Epigenetics, and Genome Editing Techniques for Food and Nutritional Security

plants Review OMICs, Epigenetics, and Genome Editing Techniques for Food and Nutritional Security Yuri V. Gogolev 1,2,* , Sunny Ahmar 3 , Bala Ani Akpinar 4 , Hikmet Budak 4 , Alexey S. Kiryushkin 5, Vladimir Y. Gorshkov 1,2, Goetz Hensel 6,7 , Kirill N. Demchenko 5 , Igor Kovalchuk 8, Freddy Mora-Poblete 3 , Tugdem Muslu 9 , Ivan D. Tsers 2 , Narendra Singh Yadav 8 and Viktor Korzun 2,10,* 1 Federal Research Center Kazan Scientific Center of Russian Academy of Sciences, Kazan Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 420111 Kazan, Russia; [email protected] 2 Federal Research Center Kazan Scientific Center of Russian Academy of Sciences, Laboratory of Plant Infectious Diseases, 420111 Kazan, Russia; [email protected] 3 Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Talca, 1 Poniente 1141, Talca 3460000, Chile; [email protected] (S.A.); [email protected] (F.M.-P.) 4 Montana BioAg Inc., Missoula, MT 59802, USA; [email protected] (B.A.A.); [email protected] (H.B.) 5 Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Plant Development, Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 197376 Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] (A.S.K.); [email protected] (K.N.D.) 6 Centre for Plant Genome Engineering, Institute of Plant Biochemistry, Heinrich-Heine-University, 40225 Dusseldorf, Germany; [email protected] 7 Centre of the Region Haná for Biotechnological and Agricultural Research, Czech Advanced Technology and Research Institute, Palacký University Olomouc, Citation: Gogolev, Y.V.; Ahmar, S.; 78371 Olomouc, Czech Republic 8 Akpinar, B.A.; Budak, H.; Kiryushkin, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB T1K 3M4, Canada; [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (N.S.Y.) A.S.; Gorshkov, V.Y.; Hensel, G.; 9 Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Sabanci University, 34956 Istanbul, Turkey; Demchenko, K.N.; Kovalchuk, I.; [email protected] Mora-Poblete, F.; et al.