The High Frontier, the Megastructure, and the Big Dumb Object

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chesley Bonestell: Imagining the Future Privacy - Terms By: Don Vaughan | July 20, 2018

HOW PRINT MYDESIGNSHOP HOW DESIGN UNIVERSITY EVENTS Register Log In Search DESIGN TOPICS∠ DESIGN THEORY∠ DESIGN CULTURE∠ DAILY HELLER REGIONAL DESIGN∠ COMPETITIONS∠ EVENTS∠ JOBS∠ MAGAZINE∠ In this roundup, Print breaks down the elite group of typographers who have made lasting contributions to American type. Enter your email to download the full Enter Email article from PRINT Magazine. I'm not a robot reCAPTCHA Chesley Bonestell: Imagining the Future Privacy - Terms By: Don Vaughan | July 20, 2018 82 In 1944, Life Magazine published a series of paintings depicting Saturn as seen from its various moons. Created by a visionary artist named Chesley Bonestell, the paintings showed war-weary readers what worlds beyond our own might actually look like–a stun- ning achievement for the time. Years later, Bonestell would work closely with early space pioneers such as Willy Ley and Wernher von Braun in helping the world understand what exists beyond our tiny planet, why it is essential for us to go there, and how it could be done. Photo by Robert E. David A titan in his time, Chesley Bonestell is little remembered today except by hardcore sci- ence fiction fans and those scientists whose dreams of exploring the cosmos were first in- spired by Bonestell’s astonishingly accurate representations. However, a new documen- tary titled Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With The Future aims to introduce Bonestell to con- temporary audiences and remind the world of his remarkable accomplishments, which in- clude helping get the Golden Gate Bridge built, creating matte paintings for numerous Hol- lywood blockbusters, promoting America’s nascent space program, and more. -

Galaktika Group: Orbital City «EFIR» «Ethereal Dwelling» Space Colony Concept by Tsiolkovsky

Galaktika group: Orbital city «EFIR» «ethereal dwelling» space colony concept by tsiolkovsky BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CONSTRUCTING A SPACE COLONY UPON THE CONCEPT BY K.E. TSIOLKOVSKY: IN-SPACE ASSEMBLING MANKIND WILL NOT FOREVER REMAIN ON EARTH, BUT IN THE PURSUIT OF LIGHT AND SPACE WILL FIRST USING MATERIALS FROM PLANETS AND ASTEROIDS TIMIDLY EMERGE FROM THE BOUNDS OF THE ATMOSPHERE, AND THEN ADVANCE UNTIL HE HAS CONQUERED THE WHOLE ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY OF CIRCUMSOLAR SPACE. PLANTS CULTIVATION HE PRESENTED HIS RESEARCHES IN THE BOOKS: BEYOND THE PLANET EARTH, BIOLOGICAL LIFE IN COSMOS, ETHEREAL ISLAND, ETC. COLONY CONCEPTS [SHORT] REVIEW BERNAL'S SPHERE, STANFORD TORUS, O’NEILL’S CYLINDER BERNAL’S SPHERE STANFORD TORUS O’NEILL’S CYLINDER JOHN DESMOND BERNAL 1929 POPULATION: STUDENTS OF THE STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1975 GERARD K. O'NEILL, 1979 POPULATION: 20 MLN. 20—30 THOUSAND INHABITANTS DIAMETER POPULATION: 10 THND. AND MORE INHABITANTS INHABITANTS DIAMETER OF CYLINDERS: 6.4 KM ABOUT 16 KM DIAMETER1.8KM AND MORE LENGTH OF CYLINDERS: 32 KM ORBITAL CITY «EFIR» scheme and characteristics TOP VIEW residential torus ASSEMBLY DOCK radiators electric power station elevator 10,000 INHABITANTS DIAMETER OF TORUS – 2 KILOMETRES variable gravity module MASS OF ORBITAL CITY – 25 MLN. TONS RESIDENTIAL AREA DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERIOR AREA RESIDENTIAL AREA CHARACTERISTICS DIAMETER OF TORUS - 2 KILOMETRES ROTATION PERIOD - ONE FULL-CIRCLE TURN PER 63 SECONDS RESIDENTIAL AREA WIDTH - 300 METERS RESIDENTIAL AREA HEIGHT - 150 METERS AREA OF RESIDENTIAL ZONE - 200 HA MAXIMUM POPULATION - 10-40 THOUSAND DESIGNED POPULATION DENSITY IS 50 PEOPLE/HA TO 200 PEOPLE/HA RESIDENTIAL AREA DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERIOR AREA LOGISTICS transport plans for passengers and cargoes ORBITAL CITY AT THE LAGRANGIAN POINT INTERPLANETARY 25 MLN. -

General Issue

Journal of the British Interplanetary Society VOLUME 72 NO.5 MAY 2019 General issue A REACTION DRIVE Powered by External Dynamic Pressure Jeffrey K. Greason DOCKING WITH ROTATING SPACE SYSTEMS Mark Hempsell MARTIAN DUST: the Formation, Composition, Toxicology, Astronaut Exposure Health Risks and Measures to Mitigate Exposure John Cain THE CONCEPT OF A LOW COST SPACE MISSION to Measure “Big G” Roger Longstaff www.bis-space.com ISSN 0007-084X PUBLICATION DATE: 26 JULY 2019 Submitting papers International Advisory Board to JBIS JBIS welcomes the submission of technical Rachel Armstrong, Newcastle University, UK papers for publication dealing with technical Peter Bainum, Howard University, USA reviews, research, technology and engineering in astronautics and related fields. Stephen Baxter, Science & Science Fiction Writer, UK James Benford, Microwave Sciences, California, USA Text should be: James Biggs, The University of Strathclyde, UK ■ As concise as the content allows – typically 5,000 to 6,000 words. Shorter papers (Technical Notes) Anu Bowman, Foundation for Enterprise Development, California, USA will also be considered; longer papers will only Gerald Cleaver, Baylor University, USA be considered in exceptional circumstances – for Charles Cockell, University of Edinburgh, UK example, in the case of a major subject review. Ian A. Crawford, Birkbeck College London, UK ■ Source references should be inserted in the text in square brackets – [1] – and then listed at the Adam Crowl, Icarus Interstellar, Australia end of the paper. Eric W. Davis, Institute for Advanced Studies at Austin, USA ■ Illustration references should be cited in Kathryn Denning, York University, Toronto, Canada numerical order in the text; those not cited in the Martyn Fogg, Probability Research Group, UK text risk omission. -

Tailored Force Fields for Space-Based Construction: Key to a Space-Based Economy Phase 1 Final Report

Tailored Force Fields for Space-Based Construction: Key to a Space-Based Economy Phase 1 Final Report NIAC-CP-01-02, USRA Subcontract 07600-091 Narayanan Komerath Sam Wanis, Balakrishnan Ganesh, Joseph Czechowski, Waqar Zaidi, Joshua Hardy, Priya Gopalakrishnan School of Aerospace Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta GA 30332-0150 [email protected] November 2002 Contents 1. Abstract Page 3 2.Introduction to Tailored Force Fields 4 Forces in steady and unsteady potential fields Time line / Application Roadmap 3.Theory connecting acoustic, optical, microwave and radio regimes. 7 4. Task Report: Acoustic Shaping 12 Prior results Inverse-design Shape Generation Software 5. Task Report: Intermediate Term: Architecture for Radiation Shield Project Near Earth 16 Shield-Building Architecture. Launcher and boxcar considerations Deployment of the Outer Grid of the Radiation Shield “Shepherd” Rendezvous-Guidance-Delivery Vehicles. 6. Task Report: Exploration of cost and architecture models for a Space-Based 24 Economy 7. Task Report: Exploration of large-scale construction using Asteroids and Radio 34 Waves Parameter space and design point Power and material requirements Technology status 8. Opportunities& Outreach related to this project 45 SEM Expt. Preparation GAS Expt. Preparation Papers, presentations, discussions Media coverage & public interest “NASA Means Business” program synergy 9. Summary of Issues Identified 49 Metal production and hydrogen recycling Resonator / waveguide technology Cost linkage to comprehensive plan Microwave demonstrator experiment 10. Conclusions 51 11. Acknowledgements 53 12. References 54 2 1. Abstract Before humans can venture to live for extended periods in Space, the problem of building radiation shields must be solved. All current concepts for permanent radiation shields involve very large mass, and expensive and hazardous construction methods. -

Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Journal.Finfar.Org

ISSN: 2342-2009 Fafnir vol 3, iss 4, pages 7–227–23 Fafnir – Nordic Journal of Science Fiction and Fantasy Research journal.finfar.org Speculative Architectures in Comics Francesco-Alessio Ursini Abstract: The present article offers an analysis on how comics authors can employ architecture as a narrative trope, by focusing on the works of Tsutomu Nihei (Blame!, Sidonia no Kishi), and the duo of Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters (Le cités obscures). The article investigates how these authors use architectural tropes to create speculative fictions that develop renditions of cities as complex narrative environments, and “places” with a distinctive role and profile in stories. It is argued that these authors exploit the multimodal nature of comics and the potential of architecture to construct complex worlds and narrative structures. Keywords: architectural tropes, comics, narrative structure, speculative fiction, world-building, multimodality Biography and contact info: Francesco-Alessio Ursini is currently a lecturer in English linguistics and literature at Jönköping University. His works on comics include a special issue on Grant Morrison for the journal ImageTexT, and the forthcoming Visions of the Future in Comics (McFarland Press), both co-edited with Frank Bramlett and Adnan Mahmutović. Speculative fiction and comics have always been tightly connected across different cultural traditions. It has been argued that the “golden era” of manga (Japanese comics) in the 70’s and 80’s is based on the preponderance of works using science/speculative fiction settings (e.g. Akira, Ohsawa 9–26). Similarly, classic works in the “Latin” comic traditions (i.e. Latin American historietas, Italian fumetti, and French/Belgian bande desineés) have long represented an ideal nexus between the speculative fiction genre and the Comics medium, one example being El Eternauta (Page 46–50). -

California State University, Northridge Low Earth Orbit

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE LOW EARTH ORBIT BUSINESS CENTER A Project submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering by Dallas Gene Bienhoff May 1985 The Proj'ectof Dallas Gene Bienhoff is approved: Dr. B. J. Bluth Professor T1mothy Wm. Fox - Chair California State University, Northridge ii iii ACKNOWLEDGEHENTS I wish to express my gratitude to those who have helped me over the years to complete this thesis by providing encouragement, prodding and understanding: my advisor, Tim Fox, Chair of Mechanical and Chemical Engineering; Dr. B. J. Bluth for her excellent comments on human factors; Dr. B. J. Campbell for improving the clarity; Richard Swaim, design engineer at Rocketdyne Division of Rockwell International for providing excellent engineering drawings of LEOBC; Mike Morrow, of the Advanced Engineering Department at Rockwell International who provided the Low Earth Orbit Business Center panel figures; Bob Bovill, a commercial artist, who did all the artistic drawings because of his interest in space commercialization; Linda Martin for her word processing skills; my wife, Yolanda, for egging me on without nagging; and finally Erik and Danielle for putting up with the excuse, "I have to v10rk on my paper," for too many years. iv 0 ' PREFACE The Low Earth Orbit Business Center (LEOBC) was initially conceived as a modular structure to be launched aboard the Space Shuttle, it evolved to its present configuration as a result of research, discussions and the desire to increase the efficiency of space utilization. Although the idea of placing space stations into Earth orbit is not new, as is discussed in the first chapter, and the configuration offers nothing new, LEOBC is unique in its application. -

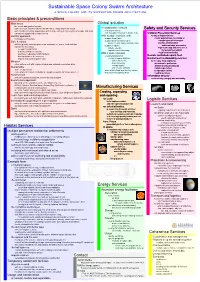

Sustainable Space Colony Swarm Architecture

Sustainable Space Colony Swarm Architecture A SPACE COLONY AND ITS SUPPORTING SWARM ARCHITECTURE Basic principles & preconditions Main focus Global solution the needs and goals of people sufficient room and the natural habitat that our body and mind needs A collaborative network Safety and Security Services with a sufficiently large population, with a large variety in ages, types of people and skills of a space colony extensively supported on many levels and its supporting swarm architecture Collision Prevention Services Holistic approach With multiple habitats, with for object impact defense, multi-layer architecture support from Earth mostly autonomous, consisting of Safe & robust support from celestial bodies: multiple types of telescopes Moon, Venus, Mars and Asteroids distributed information artificial gravity, radiation protection, atmosphere, water, food and light support in space: and knowledge processing robustness by default: safety, energy, flight vector adjustment services, compartmentalization, logistics, manufacturing by autonomous unit(s) distributed implementation, cloud overblow facility multilayer redundancy with fallback, With a space armada backup facilities & resources at Lagrangian points: Remote controlled repairs fleet impact and collision prevention clouds of space stations, Environment sustainability services with settlements, Mindset for humans, flora and fauna manufacturing, either safe or not, with regular internal and external evacuation drills air and water purification energy supply artificial gravity provisioning -

Transhumanity's Fate

ECLIPSE PHASE: TRANSHUMANITY’S FATE The Fate Conversion Guide for Eclipse Phase RYAN JACK MACKLIN GRAHAM ECLIPSE PHASE: TRANSHUMANITY’S FATE Transhumanity’s Fate: ■ Brings technothriller espionage and horror in a world of upgraded humans to Fate Core. ■ Join Firewall, and defend transhumanity in the aftermath of near annihilation by arti cial intelligence. ■ Requires Fate Core to play. Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Transhumanity’s Fate is © 2016. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License. Fate™ is a trademark of Evil Hat Productions, LLC. The Powered by Fate logo is © Evil Hat Productions, LLC and is used with permission. eclipsephase.com TRANSHUMANITY'S FATE WRITING DEDICATION Jack Graham, Ryan Macklin The Posthumans dedicate this book to Jef Smith, our ADDITIONAL MATERIAL companion of many days & nights around the table. Jef was a tireless organizer in Chicago's science-fiction/ Rob Boyle, Caleb Stokes fantasy fandom, including the Think Galactic reading EDITING group and spin-off convention, Think Galacticon. In Rob Boyle, Jack Graham 2015, he co-published the Sisters of the Revolution: A GRAPHIC DESIGN Feminist Speculative Fiction Anthology with PM Press. Adam Jury We will miss Jef's encouragement, wit, and bottomless COVER ART generosity. The person who lives large in the lives of their friends is not soon forgotten. Stephan Martiniere A portion of profits from Transhumanity's Fate will be INTERIOR ART donated to Jef's family. Rich Anderson, Nic Boone, Leanne Buckley, Anna Christenson, Daniel Clarke, Paul Davies, SPECIAL THANKS Alex Drummond, Danijel Firak, Nathan Geppert, Ryan thanks his wife, Lillian, for her support and Zachary Graves, Tariq Hassan, Josu Hernaiz, octomorph shenanigans, and blackcoat for being a font Jason Juta, Sergey Kondratovich, Ian Llanas, of feedback. -

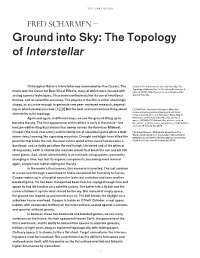

Ground Into Sky: the Topology of Interstellar

The Avery Review Fred scharmen – Ground into Sky: The Topology of Interstellar Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar was nominated for five Oscars. The Citation: Fred Scharmen, “Ground Into Sky: The Topology of Interstellar,” in The Avery Review, no. 6 movie won the Oscar for Best Visual Effects, many of which were created with (March 2015), http://averyreview.com/issues/6/ analog camera techniques. It has been controversial for its use of emotional ground-into-sky. themes, and its scientific accuracy. The physics in the film is either shockingly sloppy, or accurate enough to generate new peer-reviewed research, depend- ing on which review you read. [1] [2] But the best and most curious thing about [1] Phil Plait, “Interstellar Science: What the movie gets wrong and really wrong about black Interstellar is its topology. holes, relativity, plot, and dialogue,” Slate, http:// Again and again, in different ways, we see the ground lifting up to www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/ space_20/2014/11/interstellar_science_review_ become the sky. The first appearance of this effect is early in the movie—the the_movie_s_black_holes_wormholes_relativity.html, horizon-obliterating dust storms that sweep across the American Midwest. accessed February 24, 2015. Cooper (the main character) and his family are at a baseball game when a dust [2]: Adam Rogers, “Wrinkles in Spacetime: The Warped Astrophysics of Interstellar,” Wired, http:// storm rises, looming like a growing mountain. Drought and blight have killed the www.wired.com/2014/10/astrophysics-interstellar- plant life that binds the soil, the near-future world of the movie has become a black-hole/, accessed February 24, 2015. -

The Tragedy of the Megastructure

105 Megastructures 3 | 2018 | 1 The Tragedy of the Megastructure Valentin Bourdon PhD Candidate École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne [email protected] Valentin Bourdon is a PhD student at the Laboratory of Construction and Conservation (LCC) EPFL since 2017. His research explores the architectural challenges of the common space. In support of significant historical experiences, and contemporary subjects, such a project aims to help overcome the delay taken by architecture comparing to other disciplines in the appropriation of the notion of ‘common’. ABSTRACT Relating the megastructure to the issue of the commons is a useful exercise to understand the success and the disappearance of what Peter Reyner Banham called the “dinosaurs of the Modern Movement”. All these large-scale constructions suffered the same fate: a conflict between the promise of a large shared space and the temptation of its fragmentation. This quantitative quandary is also raised in another field by Garrett Hardin in 1968 as the ‘enclosure dilemma’. The publication of his article “The Tragedy of the Commons” sparked a broad controversy coinciding with the megastructure’s momentum. By assessing a number of theoretical correspondences, the article reexamines the impact of megastructures on the interdisciplinary debates of the time. It also considers the relationship between architecture and property as one of the possible–and tragically coincident–reasons for their success and dissolution. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2611-0075/8523 ISSN 2611-0075 Copyright © 2018 Valentin Bourdon 4.0 KEYWORDS Megastructure; Commons; Ownership; Enclosure; Anti-enclosure. Valentin Bourdon The Tragedy of the Megastructure 106 When the American ecologist Garrett Hardin publishes his famous article entitled “The Tragedy of the Commons”1 in Science, the architectural 1. -

October 2010

Page 1 Phactum October 2010 "There are only two things a child will share willingly -- PhactumPhactum communicable The Newsletter and Propaganda Organ of the diseases and his mother's age." Philadelphia Association for Critical Thinking Dr. Benjamin October 2010 Spock (1903 - 1998) editor: Ray Haupt email: [email protected] Webmaster: Wes Powers http://phact.org/ PhACT Meeting Saturday, October 16, 2010 at 2:00 PM Dr. David Cattell, Chairman of the Physics Department of Community College of Philadelphia, will host Dr. Catherine Fiorello, Professor of Psychology at Temple University. At Community College of Philadelphia. In Lecture Room C2-28 of the Center for Business and Industry. Enter at the corner of 18th and Callowhill Streets This meeting is free and open to the public. Myths of Psychology and Child Rearing Will boosting my child‘s self-esteem lead to a better life? Will cutting out sugar cure my child‘s hyperactivity? Will our children do better in school if teachers match instruction to their learning styles? Does teaching children about sex or homosexuality make them promiscuous or gay? Will holding my child back in first grade give him time to mature? Does DARE cut down on alcohol and drug use by students? Does spanking make kids more obedient? Does breastfeeding make kids smarter? Is ―teaching to the test‖ a waste of time? Is there really an epidemic of autism? Dr. Catherine Fiorello is Assistant Professor and Cartoon by Gruhn Director of the School Psychology Program at Temple [email protected] University. She is best known for her work on cognitive Used by Permission (Continued on page 2) "Random chance seems to have operated in our favor" -- Spock "In plain, non-Vulcan English, we've been lucky" -- McCoy "I believe I said that, Doctor" -- Spock (The Doomsday Machine) Page 2 Phactum October 2010 and neuropsychological assessment and is co-author of the bestselling School Neuropsychology with her colleague Brad Hale. -

Strangest of All

Strangest of All 1 Strangest of All TRANGEST OF LL AnthologyS of astrobiological science A fiction ed. Julie Nov!"o ! Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute Features G. %avid Nordley& Geoffrey Landis& Gregory 'enford& Tobias S. 'uc"ell& (eter Watts and %. A. *iaolin S#ires. + Strangest of All , Strangest of All Edited originally for the #ur#oses of 'EACON +.+.& a/conference of the Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute 0EA$1. -o#yright 0-- 'Y-N--N% 4..1 +.+. Julie No !"o ! 2ou are free to share this 5or" as a 5hole as long as you gi e the ap#ro#riate credit to its creators. 6o5ever& you are #rohibited fro7 using it for co77ercial #ur#oses or sharing any 7odified or deri ed ersions of it. 8ore about this #articular license at creati eco77ons.org9licenses9by3nc3nd94.0/legalcode. While this 5or" as a 5hole is under the -reati eCo77ons Attribution3 NonCo77ercial3No%eri ati es 4.0 $nternational license, note that all authors retain usual co#yright for the indi idual wor"s. :$ntroduction; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :)ar& $ce& Egg& =ni erse; < +..+ by G. %a id Nordley :$nto The 'lue Abyss; < 1>>> by Geoffrey A. Landis :'ac"scatter; < +.1, by Gregory 'enford :A Jar of Good5ill; < +.1. by Tobias S. 'uc"ell :The $sland; < +..> by (eter )atts :SET$ for (rofit; < +..? by Gregory 'enford :'ut& Still& $ S7ile; < +.1> by %. A. Xiaolin S#ires :After5ord; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :8artian Fe er; < +.1> by Julie No !"o ! 4 Strangest of All :@this strangest of all things that ever ca7e to earth fro7 outer space 7ust ha e fallen 5hile $ 5as sitting there, isible to 7e had $ only loo"ed u# as it #assed.; A H.