Introduction Chapter I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shruti Sangeet Academy

Shruti Sangeet Academy https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/ We provide Hindustani Classical,Semi Classical,Light Compositions,Sanskrit Shlokas and Compositions etc. About Us The Shruti Sangeet Academy is blessed to have a very motivated, sincere and dedicated group of students. Current Students are enrolled at one of three levels; Beginers, Intermediate and Advanced, based on their experience and comfort with the art form. Students follow a curriculum based on that offered by the Gandharva Mahavidhalaya . Gandharva Mahavidyalaya is an institution established in 1939 to popularize Indian classical music and dance. The Mahavidyalaya (school) came into being to perpetuate the memory of Pandit Vishnu Digamber Paluskar, the great reviver of Hindustani classical music, and to keep up the ideals set down by him. The first Gandharva Mahavidyala was established by him on 5 May 1901 at Lahore. The institution was relocated to Mumbai after 1947 and has subsequently established its administrative office at Miraj, Sangli District, Maharashtra. Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, New Delhi was established in 1939 by Padma Shri Pt. Vinaychandra Maudgalaya, from the Gwalior gharana, today it is the oldest music school in Delhi and is headed by noted Hindustani classical singer, Madhup Mudgal. At the Shruti Sangeet Academy, students up on completion of their curriculum successfully, have the option of applying and testing for the following certifications; (1) Sangeet Praveshika, equivalent to matriculation (generally a... For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/aboutus.html F a c t s h e e t Nature of Business :Service Provider CONTACT US Shruti Sangeet Academy Contact Person: Manager A1-602 Parsvnath Exotica Sector 53 Gurgaon - 122001, Haryana, India https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

A Nonlinear Study on Time Evolution in Gharana

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC Archi Banerjee1,2*, Shankha Sanyal1,2*, Ranjan Sengupta2 and Dipak Ghosh2 1 Department of Physics, Jadavpur University 2 Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 India *[email protected] * Corresponding author Archi Banerjee: [email protected] Shankha Sanyal: [email protected]* Ranjan Sengupta: [email protected] Dipak Ghosh: [email protected] © 2019 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC ABSTRACT Indian classical music is entirely based on the “Raga” structures. In Indian classical music, a “Gharana” or school refers to the adherence of a group of musicians to a particular musical style of performing a raga. The objective of this work was to find out if any characteristic acoustic cues exist which discriminates a particular gharana from the other. Another intriguing fact is if the artists of the same gharana keep their singing style unchanged over generations or evolution of music takes place like everything else in nature. In this work, we chose to study the similarities and differences in singing style of some artists from at least four consecutive generations representing four different gharanas using robust non-linear methods. For this, alap parts of a particular raga sung by all the artists were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA and MFDXA) technique. -

Artifacts and Representations of North Indian Art Music [*Ecompanion At

Oral Tradition, 20/1 (2005): 130-157 Shellac, Bakelite, Vinyl, and Paper: Artifacts and Representations of North Indian Art Music [*eCompanion at www.oraltradition.org] Lalita du Perron and Nicolas Magriel Introduction Short songs in dialects of Hindi are the basis for improvisation in all the genres of North Indian classical vocal music. These songs, bandiśes, constitute a central pillar of North Indian culture, spreading well beyond the geographic frontiers of Hindi itself. Songs are significant as being the only aspect of North Indian music that is “fixed” and handed down via oral tradition relatively intact. They are regarded as the core of Indian art music because they encapsulate the melodic structures upon which improvisation is based. In this paper we aim to look at some issues raised by the idiosyncrasies of written representations of songs as they has occurred within the Indian cultural milieu, and then at issues that have emerged in the course of our own ongoing efforts to represent khyāl songs from the perspectives of somewhat “insidish outsiders.” Khyāl, the focus of our current research, has been the prevalent genre of vocal music in North India for some 200 years. Khyāl songs are not defined by written representations, but are transmitted orally, committed to memory, and re-created through performance. A large component of our current project1 has been the transcription of 430 songs on the basis of detailed listening to commercial recordings that were produced during the period 1903-75, aspiring to a high degree of faithfulness to the details of specific performance instances. The shellac, bakelite, and vinyl records with 1 An AHRB-funded (Arts and Humanities Research Board) project, “Songs of North Indian Art Music” (SNIAM), carried out by the two authors in the Department of Music at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full -

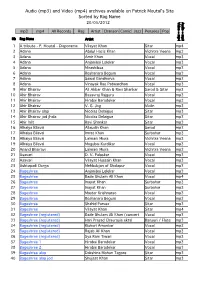

Archives Available on Patrick Moutal's Site Sorted by Rag Name Audio =Mp3 Audio 20/05/2012 =Mp4 Video

Audio (mp3) and Video (mp4) archives available on Patrick Moutal's Site Sorted by Rag Name Audio = mp3 20/05/2012 Video = mp4 mp3 mp4 All Records Rag Artist Chanson Comic Jazz Pensées Pop Nb Rag Name Artist 1 A tribute - P. Moutal - Diaporama Vilayat Khan Sitar mp4 2 Adana Abdul Haziz Khan Vichitra Veena mp3 3 Adana Amir Khan Vocal mp3 4 Adana Anjanibai Lolekar Vocal mp3 5 Adana Mirashibua Vocal mp3 6 Adana Roshanara Begum Vocal mp3 7 Adana Sawai Gandharva Vocal mp3 8 Adana Vinayak Rao Patwardhan Vocal mp3 9 Ahir Bhairav Ali Akbar Khan & Ravi Shankar Sarod & Sitar mp3 10 Ahir Bhairav Basavraj Rajguru Vocal mp3 11 Ahir Bhairav Hirabai Barodekar Vocal mp3 12 Ahir Bhairav V. G. Jog Violin mp3 13 Ahir Bhairav alap Nicolas Delaigue Sitar mp3 14 Ahir Bhairav jod jhala Nicolas Delaigue Sitar mp3 15 Ahir lalit Ravi Shankar Sitar mp3 16 Alhaiya Bilaval Allaudin Khan Sarod mp3 17 Alhaiya Bilaval Imrat Khan Surbahar mp3 18 Alhaiya Bilaval Lalmani Misra Vichitra Veena mp3 19 Alhaiya Bilaval Mogubai Kurdikar Vocal mp3 20 Anand Bhairavi Lalmani Misra Vichitra Veena mp3 21 Asavari D. V. Paluskar Vocal mp3 22 Asavari Vilayat Hussain Khan Vocal mp3 23 Ashtapadi Durga Mehbubjan of Sholapur Vocal mp3 24 Bageshree Anjanibai Lolekar Vocal mp3 25 Bageshree Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Vocal mp4 26 Bageshree Inayat Khan Surbahar mp3 27 Bageshree Inayat Khan Surbahar mp3 28 Bageshree Master Krishnarao Vocal mp3 29 Bageshree Roshanara Begum Vocal mp3 30 Bageshree Shahid Parvez Sitar mp3 31 Bageshree Vilayat Khan Sitar mp4 32 Bageshree (registered) Bade Ghulam Ali Khan -

Bhimsen Joshi and the Kirana Gharana«

Bhimsen Joshi and the Kirana Gharana« CHETAN KARNAN! I. INTRODUCIlON he Kirana ghariinii laid emphasis on melody rather than rhythm. In our times, Bhimsen Joshi has become the most popular artist of this gharana Tbecause he combines melody with vinuosity. His teacherSawaiGandharva combined melody with the euphony of his voice. Sawai Gandharva's teacher. Abdul Karim Khan, was a pioneer and the founder of the Kiranagharana. He had arare gift for making melodic phrases in any raga he chose to sing. Abdul Karim Khan had another notable disciple in Roshan Ara Begam, but Sawai Gandharva was by far his most distinguished disciple. Sawai Gandharva's important disciples are Bhimsen Joshi, Gangubai Hangal and Firoz Dastur. In later sections of this chapter I have emphasized the rugged masculinityof GangubaiHangal's voice. I have also discussed the systematic elaboration of ragas presentedby Firoz Dastur. Just as the Gwalior gharana has two lines represented by Haddu Khan and Hassu Khan, the Kirana gharana has two lines represented by Abdul Karim Khan and Abdul Wahid Khan. Abdul Wahid Khan combined melody with systematic elaboration of raga. He laid emphasis on the placid flow of music and preferred tosing in Jhoomra tala offourteen beats. By elaboratinga raga in slow tempo, he showed a facet of melody distinct from Abdul Karim Khan. His most di stinguished disciples were Hirabai Barodekar and Pran Nath, who sang with euphony in slow tempo. It is sheer good luck that the pioneers of the Kirana gharana, Abdul Karim Khan and Abdul Wahid Khan, were saved from oblivion by the gramophone COmpanies. -

The Gwalior Gharana of Khayal

THE GWALIOR GHARANA OF KHAYAL SusheeJa Misra The different gharanas in Khayal-singing have not only helped to preserve and perpetuate the older traditions through an unbroken lineage of Guru shishya-paratnpara, but also added much colour and infinite variety to Hindustani Music. In an article on "A spects of Karnatic Music", the late Sri G.N. Balasubramaniam (a famous performing artiste and scholar) wrote almost longingly:- "Unlike the Karnatak system, the Hindustani system is more elastic and flexible and comparatively free from inhibitions and restrictions. For instance, in the North there are several Gharanas--each one handling one and the same raga differently. In the South everywhere, every raga is ren dered alike". It is this scope for variety, choice of suitable style, and flights of fancy that have maintained the popul arity of the Khayal up till now. The precursors of the Khayal also used to be rendered in different styles. In ancient granthas, we come across mention of different types of "Geetis" such as "Shudhdha", "Bhinna", "Goudi", "Vesari", and "Saadhaarant", When the golden age of the Dhrupad began (during the Middle Ages), Dhrupad-gayan also had developed four "Baants" (meaning styles, or schools) namely, :-"Goudi" or "Gobarhari", "Daggur", "Khandar", and "Nowhar". When the majestic and ponderous Dhrupad had to give place to the .classico-romantic Khayal-form, the latter was developed and perfected into various styles which came to be known as "Gharanas", These "gharanas" gave an attractive variety to Khayal-singing,-each "gharana" developing its own distinctive features, although all of them were deeply rooted in a common underlying tradition or "Susampradaaya". -

RAHIMAT KHAN, DISCOGRAPHY, KHYAL SINGER | Bajakhana

bajakhana MICHAEL KINNEAR'S WEBSITE INTO EARLY SOUND RECORDINGS HOME RECORD LABELS DISCOGRAPHIES ARTICLES PUBLICATIONS CONTACT CHECKOUT ← Previous Next → RAHIMAT KHAN, DISCOGRAPHY, KHYAL SINGER Ustad RAHIMAT KHAN Sahib KHYAL SINGER, c. 1860 – 1922 A BIO – DISCOGRAPHY By Michael Kinnear Excerpt from “Sangeet Ratna – The Jewel of Music” Khan Sahib Abdul Karim Khan – A Bio Discography by Michael Kinnear, Published 2003 Rahimat Khan with Vishnupant Chhatre and his brother Vinayakra Chhatre Rahimat Khan at Dharwararkar https://bajakhana.com.au/wp- 00:00 00:00 content/uploads/2019/06/rahmatkhan_malkauns.mp3 Rahimat Khan – Malkauns https://bajakhana.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/rahmatkhan_yaman-1.mp3 RAHIMAT KHAN is one of the legendary figures of Hindustani music of the 19th centuryand a leading exponent of the Gwalior Gharana. Precise or factual information about his life is rather sketchy and for the most part appear to be anecdotal and the lineage of his family varies from one account to another. Rahimat Khan is believed to have been born at Gwalior in 1860 and was one of the sons of Haddu Khan, who along with his elder brother Hassu Khan had achieved fame as Khayal singers at the court of Gwalior. The ancestral home of this family was originally at Hussainpur, which later became known as Husanpur-Lohari, a twin village some twenty miles northwest of Muzaffarnagar in the district of the same name, and some twenty miles north of Kairana. This area north of Delhi is generally known as the ‘Bara-basti’. The area has produced a number of gifted families of musicians of Pathan origin, but it is notknown for certain if the generations of this particular family originally came from Husanpur Lohari, or had migrated there from Lucknow during the rulership of Nawab Saddat Ali Khan II (r.1797-1814). -

Annual Report-2004-2005

2004-2005 THIS IS THE 44th Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing February 2004 up to 31 January 2005. It will be placed before the 49th Annual General Body Meeting of the Centre, to be held on the 28th of March 2005. The tenure of the existing elected representatives on the Executive Committee and the Board of Trustees, from both the Individual and Corporate membership segments, will come to an end on the 31st of March 2005. The Centre would like to place on record its gratitude to the two outgoing Trustees, Shri S.K. Singh and Dr Arun Nigavekar, and to Shri Inder Malhotra, Lt. Gen. (retd) A. S. Kalkat, Dr S. M. Dewan, Dr R. K. Pachauri, Shri M. H. Ansari and Prof. (Mrs.) Sneh Bhargava (members of the Executive Committee), for the interest they have taken and the valuable support they provided towards the Centre’s functioning. The process of filling up the vacancies for the ensuing two-year period, 1 April 2005 to March 2007, has been underway since December 2004. The results of the elections will be announced in the forthcoming Annual General Body Meeting of the Centre. In the year’s national honours list, twenty-five of the Centre’s distinguished Members were vested with Padma awards. Dr Karan Singh, Member of Parliament and a Life Trustee was awarded the Padma Vibhushan. Earlier, Dr Kapila Vatsyayan, also a Life Trustee, and a Fellow of the Lalit Kala Akademi, was conferred the ‘Lalit Kala Ratna Award’ by the Akademi on the occasion of its golden jubilee celebrations. -

Dr. RANJANI RAMACHANDRAN Hindustani Classical Vocalist

Dr. RANJANI RAMACHANDRAN Hindustani Classical Vocalist, Assistant Professor, Department of Hindusthani Classical Music, Sangit Bhavana, Visva Bharati, Santiniketan Email (Official): [email protected] Dr. Ranjani Ramachandran is a well known khayal vocalist of the Gwalior and Jaipur gharana having trained under eminent gurus including Padmashree Pandit Ulhas Kashalkar, Vidushi Veena Sahasrabuddhe and Pandit Kashinath Bodas. Ranjani also received guidance from Vidushi Girija Devi, acquiring a rich repertoire of Thumri, Dadra, Chaiti and Kajri. She has performed in prestigious platforms in India and abroad. Her research interests include music analysis, archiving and interdisciplinary studies. An ex- scholar of the prestigious ITC Sangeet Research Academy, she is a recipient of many awards including the Charles Wallace Research grant from the UK and has been a long time collaborator with ethnomusicologists at the Durham University in UK. She is currently working as an Assistant professor and teaches vocal music at the Department of Hindustani classical music in Sangit Bhavana at Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal. Ranjani is a Doctorate in vocal music. Her doctoral thesis focused on studying the stylistic diversity within the Gwalior Gharana through analysis of recordings of a few Gwalior Gharana vocalists from the 20th Century. Awards and accolades: • Charles Wallace Fellow,Charles Wallace India Trust (CWIT) Research Grant, UK, 2015 • Ramkrishnabua Vaze Yuva Gayak Puraskar 2013 • ‘Surmani’ Award, Sur -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’, Mumbai ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume - Annual: TRN 2007 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’, Mumbai ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume - Annual: TRN 2007 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Branches: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded, Tuljapur, Baroda, Amravati ============================================================= Feature Article in this Issue: Gramophone Celebrities-II Other articles : Teheran Records, O. P. Nayyar. 1 ‘The Record News’ – Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members --------------------------- V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US$ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full membership fee and get a copy