To Get the File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Classical Music Conference Culture of North India with Special Reference to Kolkata

https://doi.org/10.37948/ensemble-2020-0201-a016 CLASSICAL MUSIC CONFERENCE CULTURE OF NORTH INDIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO KOLKATA Samarpita Chatterjee 1 , Sabyasachi Sarkhel 2 Article Ref. No.: Abstract: 20010236N2CASE The music of any country has its own historical and cultural background. Social changes, political changes, and patronage changes may influence the development of music. This may affect the practices in the field of music. This present study does the scrutiny of the broad sociocultural settings in context to the music conferences of India. The study then mainly probes and explores the prime music conferences of India, with special reference Article History: to Kolkata, from a century ago till the present time. It shows the role of Submitted on 02 Jan 2020 music conferences in disseminating interest and appreciation of Classical Accepted on 07 May 2020 music among the common public. The cultural climate shaped under the Published online on 09 May 2020 domination of British rule included the shift of patronage from aristocratic courts to wealthy persons and a mercantile class of urban Kolkata. This allowed the musicians to earn a livelihood, and at the same time, provided them with a new range of opportunities in the form of an increasing number of music conferences. This happened at a time when a new class of Keywords: Western-educated elites was formed in Kolkata. Analyzing the present patronage, british, stage scenario, made it clear that Kolkata still leads in the number of music performances, north indian, musical festivals / Classical music conferences. The present study also points out genre, hindustani music, shastriya the contemporary complexities that conference organizers face, and to sangeet, british, post independence conclude, incorporates suggestions to sustain the culture of the conference. -

Raja Mansingh Tomar Music and Arts University

RAJA MANSINGH TOMAR MUSIC AND ARTS UNIVERSITY Mahadaji Chok, Achaleshwar Mandir Marg, Gwalior – 474009, Madhya Pradesh Tel : 0751-2452650, 2450241, 4011838, Fax : 0751-4031934 Email : [email protected]; [email protected] Website : http://www.rmtmusicandartsuniversity.com Raja Mansingh Tomar Music and Arts University has been established at Gwalior under the Madhya Pradesh Act No. 3 of 2009 vide Raja Mansingh Tomar Sangit Evam Kala Vishwavidyalaya Adhiniyam, 2009. Unity in diversity is the cultural characteristic of India. The statements is fully in consonant with reference to Madhya Pradesh. It is one of the most recognized cetnres of arts and music from ancient times. It was also a centre for the teaching of Lord Krishna during the period of the Mahabharata in Sandipani Ashram of Ujjain. During the period of the Ramayan it was Chitrakoot which became the witness of Lord Rama’s penances. So many rivers create the aesthetic beauty of Madhya Pradesh, Apart from the various rivers such as Narmada, Kshipra, Betava, Sone, Indravati, Tapti and Chambal. Madhya Pradesh has also given birth to many saints, poets, musicians and great persons. Ashoka the great, was associated with Ujjaini and Vidisha, Mahendra and Sanghamitra started spreading the teachings of Buddhism from here. Madhya Pradesh is the pious land of Kalidas, Bhavabhuti, Tansen, Munj, Raja Bhoj, Vikramaditya, Baiju Bawra, Isuri, Patanjali Padmakar, and the great Hindi poet Keshav. This is the province which always encouraged and motivated the artists. Raja Man Singh Tomar also nutured the arts of music, dance and fine arts here. From time immemorial Madhya Pradesh has been resonated with the waves of Music. -

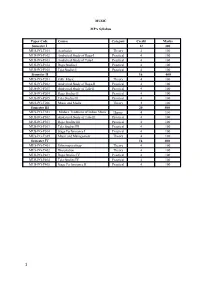

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute

University of Mauritius Mahatma Gandhi Institute Regulations And Programme of Studies B. A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) (Review) - 1 - UNIVERSITY OF MAURITIUS MAHATMA GANDHI INSTITUTE PART I General Regulations for B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 1. Programme title: B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) 2. Objectives To equip the student with further knowledge and skills in Vocal Hindustani Music and proficiency in the teaching of the subject. 3. General Entry Requirements In accordance with the University General Entry Requirements for admission to undergraduate degree programmes. 4. Programme Requirement A post A-Level MGI Diploma in Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) or an alternative qualification acceptable to the University of Mauritius. 5. Programme Duration Normal Maximum Degree (P/T): 2 years 4 years (4 semesters) (8 semesters) 6. Credit System 6.1 Introduction 6.1.1 The B.A (Hons) Performing Arts (Vocal Hindustani) programme is built up on a 3- year part time Diploma, which accounts for 60 credits. 6.1.2 The Programme is structured on the credit system and is run on a semester basis. 6.1.3 A semester is of a duration of 15 weeks (excluding examination period). - 2 - 6.1.4 A credit is a unit of measure, and the Programme is based on the following guidelines: 15 hours of lectures and / or tutorials: 1 credit 6.2 Programme Structure The B.A Programme is made up of a number of modules carrying 3 credits each, except the Dissertation which carries 9 credits. 6.3 Minimum Credits Required for the Award of the Degree: 6.3.1 The MGI Diploma already accounts for 60 credits. -

Ph.D. Entrance Examination Subject: Music

Ph.D. Entrance Examination Subject: Music Time : 2 Hrs. Max. M. 100 Mim. M. 50 u¨V % lÒh ç“u gy djsaA çR;sd ç“u 1 vad dk gSA çR;sd ç“u d¢ pkj fodYi gSa] lgh fodYi pqfu,A Note : Attempt all questions. Each question carries 1 mark. Each question has four opptions, Choose the correct option. 1- fuEu esa ls d©u lk Loj vpy gSa\ ¼~v½ eè;e ¼c½ fj’kÒ ¼l½ xkaèkkj ¼n½ ‘kM~t Which Swaras is Achal of following? (a) Madhayam (b) Rishabh (c) Gandhar (d) Shadaj 2- Xokfy;j Äjkus d¢ tUenkrk d©u Fks\ ¼~v½ m- vCnqy djhe [k+k¡ ¼c½ m- uRFku ihjc[+“k ¼l½ m- vYykmíhu [kk¡ ¼n½ ia- oklqnso cqvk t¨“kh Who was the founder of Gwalior Gharana? (a) Ustad Abdul Karim Khan (b) Ustad Nathanpeer baksh (c) Ustad Allauddin Khan (d) Pt. Vasudev Bua Joshi 3- fuEu esa ls d©u lqçfl) fgUnqLrkuh “kkL=h; laxhr xk;d@xkf;dk gSa\ ¼~v½ ia- gfjçlkn p©jfl;k ¼c½ ia- fd“ku egkjkt ¼l½ Jherh ,u- jkte~ ¼n½ Jherh xaxwckà gaxy Who amongst the following is renowned in Hindustani classical vocal singer? (a) Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasiya (b) Pt. Kishan Maharaj (c) Smt. N. Rajam (d) Smt. Gangubai Hangal 4- ia- vu¨[ks yky fdl {ks= dh fo“ks’kK ekus x;s\ ¼~v½ flrkj ¼c½ rcyk ¼l½ xk;u ¼n½ y¨dlaxhr In which field has Pt. Anokhelal distinguished? (a) Sitar (b) Tabla (c) Vocal (d) Folk Music 5- Äjkus ls vki D;k le>rs gSa\ ¼~v½ “kkL=h; fgUnqLrkuh laxhr dh y¨dfç; “kSyh ¼c½ laxhr {ks= d¢ laxhrK¨a dk lewg ¼l½ xk;u dh ijEijkxr “kSyh ¼n½ laxhr dh ijEijk t¨ oa“k ,oa f“k’; J`a[kyk ls lEcfUèkr g¨rh gSA What do you mean by Gharana? (a) A popular musical form of Hindustani classical music (b) A group of musicians in -

12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, Vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, Tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, Harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, Tanpuras

From left to right: Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, Shampa Bhattacharya, Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, Michael Harrison, Kedar Naphade Photo credit: Ira Meistrich, edited by Tina Psoinos 12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, tanpuras TRANSCENDENCE Raga Desh: Man Rang Dani, drut bandish in Jhaptal – 9:45 Raga Shahana: Janeman Janeman, madhyalaya bandish in Teental – 14:17 Raga Jhinjhoti: Daata Tumhi Ho, madhyalaya bandish in Rupak tal, Aaj Man Basa Gayee, drut bandish in Teental – 25:01 Raga Bhupali: Deem Dara Dir Dir, tarana in Teental – 4:57 Raga Basant: Geli Geli Andi Andi Dole, drut bandish in Ektal – 9:05 Recorded on 29-30 May, 2015 at Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY Produced and Engineered by Adam Abeshouse Edited, Mixed and Mastered by Adam Abeshouse Co-produced by Shampa Bhattacharya, Michael Harrison and Peter Robles Sponsored by the American Academy of Indian Classical Music (AAICM) Photography, Cover Art and Design by Tina Psoinos 2 NI 6340 NI 6340 11 at Carnegie Hall, the Rubin Museum of Art and Raga Music Circle in New York, MITHAS in Boston, A True Master of Khayal; Recollections of a Disciple Raga Samay Festival in Philadelphia and many other venues. His awards are many, but include the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar by the Sangeet Natak Aka- In 1999 I was invited to meet Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, or Khan Sahib as we respectfully call him, and to demi, New Delhi, 2015 and the Gandharva Award by the Hindusthan Art & Music Society, Kolkata, accompany him on tanpura at an Indian music festival in New Jersey. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

University of Mumbai Department of Music Sample of MCQ Question Paper for Students M.Mus Part 2 Paper -V Course Name – Music

University of Mumbai Department of Music Sample of MCQ Question Paper for Students M.mus part 2 paper -V Course Name – Music Education Paper/Subject Code_________ Student’s Seat No._____ Instrructions; 1. All the Questions are Compulsory Total Marks – 50 2. All Questions Carry Equal Marks 1. Name the artist from Kirana Gharana among the following a. Sangmeshwar Gurav b. Mallikarjun Mansoor c. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit d. Faiyyaz Khan 2. Name the student of Ustad Allauddin Khan a. Ust. Aliakbar Khan b. Kishore Kumar c. Gayatri Chitre d. MAnik Varma 3. Name disciple of Ust. Alladiya Khan among the following a. Kesarbai b. Hirabai c. Begam Akhtar d. Parveen Sultana 4. Where the Indira Kala Vishwavidyalay is Located? a. Pune b. Mumbai c. Khairagadh d. Nagpur 5. Among following who is awarded with Padmavibhushan? a. Pt. Rakesh Chaurasia b. Pt. Jasraj c. Pt. Mukund Lath d. Sumitra Guha 6. Who was the Guru of Kumar Gandharva? a. Saraswati Rane b. B.R. Deodhar c. Kagalkar buwa d. Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale 7. Who had written book on Aesthetics of Indian Music? a. Sudheer Nayak b. Manjiri Sinha c. Rama Deodhar d. Ashok D. Ranade 8. Among the following which is a performing art? a. Natya b. Pottery c. Poetry d. Sculpture 9. Who was titled as Swarbhaskar ? a. Prabhakar Karekar b. Vinay Mishra c. Rajan Sajan Mishra d. Bhimsen Joshi 10. Who was the only direct disciple of Kesarbai Kerkar? a. Dhondutai Kulkarni b. Parmeshwar Hegade c. Pahadi Sanyal d. Jaimala Shiledar 11. Name the famous stage actor-singer a. Saleel Choudhari b. -

The Age Before Vinyl 7/4/20, 10:54 AM

The age before vinyl 7/4/20, 10:54 AM New e-paper Sign in Explore Saturday, 4 July 2020 Home Home >mint-lounge >features >The age before vinyl Latest Trending My Reads Pivot Or Perish Market Dashboard India-China Face-Off The Future Of Covid Tracker Lounge The Wonder That Was The Cylinder: By A.N. Sharma and Anukriti A. Sharma, Coronavirus Spenta Multimedia, 300 pages, Rs6,000 (including the DVD). India2Global Emerging Tech Conclave The age before vinyl 3 min read . 25 Oct 2014 Narendra Kusnur A tome on cylinder recordings by Gauhar Jan, Rabindranath Tagore and others Topics The Wonder That Was The Cylinder Vinyl records AN Sharma and Anukriti A Sharma Music Books It was another era, another technology. Before vinyl records ruled the scene in the early 20th century, the music industry was dominated by wax cylinders. The voices of some of India’s most reputed artistes were recorded on these hollow rolls; sadly, many of them have been lost. In their book, The Wonder That Was The Cylinder, A.N. Sharma and his daughter Anukriti present a detailed thesis on this fascinating subject. Aiding them in the research is their collection of rare cylinders, which they found lying with scrap dealers. Included are recordings of classical doyens Ustad https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/7EOnGuNasdjbQfQU9IckrK/The-age-before-vinyl.html Page 1 of 14 The age before vinyl 7/4/20, 10:54 AM Alladiya Khan and Pandit Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, Marathi music legends Bhaurao Kolhatkar, Bhaskarbuwa Bakhale and Balgandharva, and the father of Indian cinema, Dadasaheb Phalke. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full