Women's Autonomy, Equality and Reproductive Health in International Human Rights: Between Recognition, Backlash and Regressive Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern-Day Slavery & Human Rights

& HUMAN RIGHTS MODERN-DAY SLAVERY MODERN SLAVERY What do you think of when you think of slavery? For most of us, slavery is something we think of as a part of history rather than the present. The reality is that slavery still thrives in our world today. There are an estimated 21-30 million slaves in the world today. Today’s slaves are not bought and sold at public auctions; nor do their owners hold legal title to them. Yet they are just as surely trapped, controlled and brutalized as the slaves in our history books. What does slavery look like today? Slaves used to be a long-term economic investment, thus slaveholders had to balance the violence needed to control the slave against the risk of an injury that would reduce profits. Today, slaves are cheap and disposable. The sick, injured, elderly and unprofitable are dumped and easily replaced. The poor, uneducated, women, children and marginalized people who are trapped by poverty and powerlessness are easily forced and tricked into slavery. Definition of a slave: A person held against his or her will and controlled physically or psychologically by violence or its threat for the purpose of appropriating their labor. What types of slavery exist today? Bonded Labor Trafficking A person becomes bonded when their labor is demanded This involves the transport and/or trade of humans, usually as a means of repayment of a loan or money given in women and children, for economic gain and involving force advance. or deception. Often migrant women and girls are tricked and forced into domestic work or prostitution. -

The Right to Reparations for Acts of Torture: What Right, What Remedies?*

96 STATE OF THE ART The right to reparations for acts of torture: what right, what remedies?* Dinah Shelton** 1. Introduction international obligation must cease and the In all legal systems, one who wrongfully wrong-doing state must repair the harm injures another is held responsible for re- caused by the illegal act. In the 1927 Chor- dressing the injury caused. Holding the zow Factory case, the PCIJ declared dur- wrongdoer accountable to the victim serves a ing the jurisdictional phase of the case that moral need because, on a practical level, col- “reparation … is the indispensable comple- lective insurance might just as easily provide ment of a failure to apply a convention and adequate compensation for losses and for fu- there is no necessity for this to be stated in ture economic needs. Remedies are thus not the convention itself.”1 Thus, when rights only about making the victim whole; they are created by international law and a cor- express opprobrium to the wrongdoer from relative duty imposed on states to respect the perspective of society as a whole. This those rights, it is not necessary to specify is incorporated in prosecution and punish- the obligation to afford remedies for breach ment when the injury stems from a criminal of the obligation, because the duty to repair offense, but moral outrage also may be ex- emerges automatically by operation of law; pressed in the form of fines or exemplary or indeed, the PCIJ has called the obligation of punitive damages awarded the injured party. reparation part of the general conception of Such sanctions express the social convic- law itself.2 tion that disrespect for the rights of others In a later phase of the same case, the impairs the wrongdoer’s status as a moral Court specified the nature of reparations, claimant. -

Feminicide in Latin America.Pdf

Feminicide in Latin America Authors: Paula Norato, Gabriela Ramos-King and Alejandro Rodriguez Course: Power and Health in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2019 Abstract Violence against women has existed for centuries, specifically in Latin America as nation-states use this issue to oppress communities. Torture is used to strip women of their female identities in order to solicit information, obstetric violence is used to make women passive, and groups of women who speak and protest against feminicide are kidnapped, murdered, and raped. Governments disregard the existence of feminicide and do not create policies to act against it or programs to help those affected. Feminicide is carried out through state violence, suppression and restriction of reproductive and sexual rights, as well as a lack of policy and programs addressing socio-cultural dynamics around feminicide. This paper goes into depth at how each of these factors contribute to feminicide, what some countries are doing to fight against, which countries let it continue, and the groups of women both affected and acting against feminicide. Key Words: Feminicide, Systematic Violence, Reproductive rights, State Violence, Feminicide Policy Violence against women has existed for a very long time and has developed over centuries to be used as a tool to oppress communities. In today’s day and age, organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) are joining together with Latin American governments and feminist researchers to better define violence against women in order to take action against it. The two most common terms used in this field are femicide and feminicide, however since research on this topic only began 30 years ago there is still room for improvement in terms of definitions. -

Teacher Lesson Plan an Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities

Teacher Lesson Plan An Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities Lesson 2: Introduction to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Note: The Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities resource has been designed as two unique lesson plans. However, depending on your students’ level of engagement and the depth of content that you wish to explore, you may wish to divide each lesson into two. Each lesson consists of ‘Part 1’ and ‘Part 2’ which could easily function as entire lessons on their own. Key Learning Areas Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS); Health and Physical Education Year Group Years 5 and 6 Student Age Range 10-12 year olds Resources/Props • Digital interactive lesson - Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities https://www.humanrights.gov.au/introhumanrights/ • Interactive Whiteboard • Note-paper and pens for students • Printer Language/vocabulary Human rights, responsibilities, government, children’s rights, citizen, community, individual, law, protection, values, beliefs, freedom, equality, fairness, justice, dignity, discrimination. Suggested Curriculum Links: Year 6 - Humanities and Social Sciences Inquiry Questions • How have key figures, events and values shaped Australian society, its system of government and citizenship? • How have experiences of democracy and citizenship differed between groups over time and place, including those from and in Asia? • How has Australia developed as a society with global connections, and what is my role as a global citizen?” Inquiry and Skills Questioning • -

Femicide and the Feminist Perspective

HSX15410.1177/108876791142 4245414541Taylor and JasinskiHomicide Studies Homicide Studies 15(4) 341 –362 Femicide and the © 2011 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: http://www. Feminist Perspective sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1088767911424541 http://hs.sagepub.com Rae Taylor1 and Jana L. Jasinski2 Abstract The gender disparity in intimate killings underscores the need for close attention to the phenomenon of intimate partner–perpetrated femicides and theories useful in understanding this pervasive and enduring problem. The most overarching paradigm used is that of the feminist perspective. The purpose of this article is to review the tenets of feminist theory as the most viable and efficacious framework for understanding and explaining intimate partner–perpetrated femicide, to highlight empirical evidence supporting the strength and value of this perspective, to address the contentions of those in opposition to this perspective, and to provide research and policy implications targeted at greater understanding, and, ultimately, lower rates of femicide. Keywords femicide, feminist theory, intimate partner violence, intimate partner homicide, violence against women In the United States, slightly more than 16,000 individuals are victims of homicide each year (Fox & Zawitz, 2007), and men comprise the majority of victims and offend- ers of these homicides. For a number of years now, researchers have examined patterns of homicide victimization and offending to try to determine theoretical and empirical explanations for observed trends. Research considering demographic characteristics of homicide victims including gender, for example, is extensive (e.g., Gauthier & Bankston, 2004; Gruenewald & Pridemore, 2009). This research has considered not only gender differences in homicide prevalence over time but also gender differences in the victim–offender relationship (e.g., Swatt & He, 2006). -

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights Preamble Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in cooperation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge, Now, therefore, The General Assembly, Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction. -

Abolishing Corporal Punishment of Children

Abolishing corporal punishment of children Abolishing corporal punishment of children Questions and answers Why should it be made illegal to hit children for disciplinary reasons? What right does the state have to interfere in the way children are raised? How can public attitudes be shifted towards positive and non-violent parenting? These Questions and answers and many other issues are discussed in this booklet, intended for parents, policy makers, lawyers, children’s advocates and other people working with children, all of whom have a vested interest in their well-being. Divided into four main parts, this booklet defines corporal punishment of children; gives reasons, based on international law, why corporal punishment should be abolished; discusses how abolition can be achieved; and debunks myths and public fears hovering around the issue. Punishing children physically is an act of violence and a violation of children’s human rights. Every nation in Europe has a legal obligation to join the 17 European nations that have already enacted a total ban on corporal punishment of children. www.coe.int The Council of Europe has 47 member states, covering virtually the entire continent of Europe. It seeks to develop common democratic and legal principles based on the European Convention on Human Rights and other reference texts on the protection of individuals. Ever since it was founded in 1949, in the aftermath of the Second World War, the Council of Europe has symbolised reconciliation. ISBN 978-92-871-6310-3 BUILDING A EUROPE FOR AND WITH CHILDREN 9:HSTCSH=V[XVUX: http://book.coe.int €12/US$18 Council of Europe Publishing Abolishing corporal punishment of children Questions and answers Building a Europe for and with children www.coe.int/children Council of Europe Publishing 1 Contents French edition Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Comments on the Prohibition of Torture and Inhuman, Cruel, Or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment in Libya’S Draft Constitutional Recommendations

Comments on the prohibition of torture and inhuman, cruel, or degrading treatment or punishment in Libya’s Draft Constitutional Recommendations I. The Prohibition of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Torture is a crime and serious human rights violation that has devastating consequences for its victim, his or her family and whole communities. The practice of torture is in stark contrast to the rule of law. The abhorrent nature of the crime is recognised in constitutions around the world and in international law, under which torture is absolutely prohibited. This absolute prohibition means that there are no exceptions and no justifications for this crime, even in times of emergency. Libya is party to a number of key international and regional treaties that enshrine the absolute prohibition of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (ill- treatment). These include the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (articles 7 and 10), the 1981 African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) (article 5), the 1984 United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT) and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (article 37). Under international law, states parties to a treaty are bound to implement its provisions and must ensure that their domestic law complies with their treaty obligations.1 According to article 2 UNCAT ‘Each State Party shall take effective legislative, administrative, judicial or other measures to prevent acts of torture in any territory under its jurisdiction.’2 Libya therefore has a duty to enshrine the prohibition of torture in its domestic legal order. -

The Right to Be Free from Torture and Cruel, Inhuman Or Degrading

Equality and Human Rights Commission Following Grenfell: the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment Following Grenfell: the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment This briefing focuses on the prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, including the meaning of these terms, case law and relevance to Grenfell. The briefing forms part of a series explaining human rights issues raised by the Grenfell Tower fire: the right to life, adequate and safe housing, inhuman or degrading treatment, access to justice, equality and non-discrimination, and children’s rights. What is the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and what is its source in international law? The survivors of the Grenfell Tower fire and many of those who witnessed it, or were otherwise affected by it, have suffered great harm, potentially reaching the threshold of inhuman and degrading treatment. The right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (‘c/i/d treatment’) or punishment is established in the UN Convention Against Torture (CAT) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), at an international level, and the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), at a regional level.1 The UK Government has ratified CAT, ICCPR and the ECHR. By doing so, it has committed to the human rights standards set out in these treaties under international law. This means that all UK governments and public bodies – central, local and devolved – and all public officials, have to take appropriate measures to protect people from torture and c/i/d treatment. -

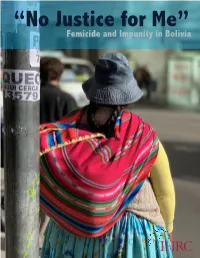

Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia “No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia

“No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia “No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia Acknowledgements Tis report was researched and written by Fabiola Alvelais, JD ‘20, Isabel Pitaro, JD ’20, Julia Wenck, ‘20, and Clinical Instructor Tomas Becker, JD ‘09, of Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) as well as Gemma Canham, BA ‘20, of Queens University Belfast. Te Clinic wishes to thank the many individuals who were willing to speak with us and share their stories to make this report possible. Contents 1 I. Executive Summary 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 7 Minimum Guide- Femicide 3 II. Methodology 4 III. -

Forms of Femicide

29 Forms of Femicide Facilitate. Educate. Collaborate. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the AUTHOR views of the Government of Ontario or the Nicole Etherington, Research Associate, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women Against Women & Children. While all and Children, Faculty of Education, Western University. reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this publication, no liability is assumed for any errors or omissions. SUGGESTED CITATION Etherington, N., Baker, L. (June 2015). Forms of Femicide. Learning Network Brief (29). London, Ontario: Learning The Learning Network is an initiative of the Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children. against Women & Children, based at the http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Faculty of Education, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada. Download copies at: http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/ Copyright: 2015 Learning Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women and Children. www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Funded by: Page 2 of 5 Forms of Femicide Learning Network Brief 29 Forms of Femicide Femicide is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘the intentional killing of women because they are women; however, a broader definition includes any killings of women and girls.’i Femicide is the most extreme form of violence against women on the continuum of violence and discrimination against women and girls. There are numerous manifestations of femicide recognized by the Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Office. ii It is important to note that the following categories of femicide are not always discrete and may overlap in some instances of femicide. -

American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man

AMERICAN DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF MAN (Adopted by the Ninth International Conference of American States, Bogotá, Colombia, 1948) WHEREAS: The American peoples have acknowledged the dignity of the individual, and their national constitutions recognize that juridical and political institutions, which regulate life in human society, have as their principal aim the protection of the essential rights of man and the creation of circumstances that will permit him to achieve spiritual and material progress and attain happiness; The American States have on repeated occasions recognized that the essential rights of man are not derived from the fact that he is a national of a certain state, but are based upon attributes of his human personality; The international protection of the rights of man should be the principal guide of an evolving American law; The affirmation of essential human rights by the American States together with the guarantees given by the internal regimes of the states establish the initial system of protection considered by the American States as being suited to the present social and juridical conditions, not without a recognition on their part that they should increasingly strengthen that system in the international field as conditions become more favorable, The Ninth International Conference of American States AGREES: To adopt the following AMERICAN DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF MAN Preamble All men are born free and equal, in dignity and in rights, and, being endowed by nature with reason and conscience, they should conduct themselves as brothers one to another. The fulfillment of duty by each individual is a prerequisite to the rights of all.