Feminicide in Latin America.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Femicide and the Feminist Perspective

HSX15410.1177/108876791142 4245414541Taylor and JasinskiHomicide Studies Homicide Studies 15(4) 341 –362 Femicide and the © 2011 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: http://www. Feminist Perspective sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1088767911424541 http://hs.sagepub.com Rae Taylor1 and Jana L. Jasinski2 Abstract The gender disparity in intimate killings underscores the need for close attention to the phenomenon of intimate partner–perpetrated femicides and theories useful in understanding this pervasive and enduring problem. The most overarching paradigm used is that of the feminist perspective. The purpose of this article is to review the tenets of feminist theory as the most viable and efficacious framework for understanding and explaining intimate partner–perpetrated femicide, to highlight empirical evidence supporting the strength and value of this perspective, to address the contentions of those in opposition to this perspective, and to provide research and policy implications targeted at greater understanding, and, ultimately, lower rates of femicide. Keywords femicide, feminist theory, intimate partner violence, intimate partner homicide, violence against women In the United States, slightly more than 16,000 individuals are victims of homicide each year (Fox & Zawitz, 2007), and men comprise the majority of victims and offend- ers of these homicides. For a number of years now, researchers have examined patterns of homicide victimization and offending to try to determine theoretical and empirical explanations for observed trends. Research considering demographic characteristics of homicide victims including gender, for example, is extensive (e.g., Gauthier & Bankston, 2004; Gruenewald & Pridemore, 2009). This research has considered not only gender differences in homicide prevalence over time but also gender differences in the victim–offender relationship (e.g., Swatt & He, 2006). -

Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia “No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia

“No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia “No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia Acknowledgements Tis report was researched and written by Fabiola Alvelais, JD ‘20, Isabel Pitaro, JD ’20, Julia Wenck, ‘20, and Clinical Instructor Tomas Becker, JD ‘09, of Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) as well as Gemma Canham, BA ‘20, of Queens University Belfast. Te Clinic wishes to thank the many individuals who were willing to speak with us and share their stories to make this report possible. Contents 1 I. Executive Summary 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 7 Minimum Guide- Femicide 3 II. Methodology 4 III. -

Forms of Femicide

29 Forms of Femicide Facilitate. Educate. Collaborate. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the AUTHOR views of the Government of Ontario or the Nicole Etherington, Research Associate, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women Against Women & Children. While all and Children, Faculty of Education, Western University. reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this publication, no liability is assumed for any errors or omissions. SUGGESTED CITATION Etherington, N., Baker, L. (June 2015). Forms of Femicide. Learning Network Brief (29). London, Ontario: Learning The Learning Network is an initiative of the Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children. against Women & Children, based at the http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Faculty of Education, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada. Download copies at: http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/ Copyright: 2015 Learning Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women and Children. www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Funded by: Page 2 of 5 Forms of Femicide Learning Network Brief 29 Forms of Femicide Femicide is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘the intentional killing of women because they are women; however, a broader definition includes any killings of women and girls.’i Femicide is the most extreme form of violence against women on the continuum of violence and discrimination against women and girls. There are numerous manifestations of femicide recognized by the Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Office. ii It is important to note that the following categories of femicide are not always discrete and may overlap in some instances of femicide. -

FEMICIDE and the MEDIA: Do Reporting Practices Normalize Gender-Based Violence?

Policy Brief No. 1 FEMICIDE AND THE MEDIA: Do reporting practices normalize gender-based violence? SUMMARY Feminist activism in the context of the novel coronavirus has cast renewed light on an extreme form of gender-based violence: femicide. Several countries in Latin America reported spikes in femicide in the early months of state-wide lockdowns, even in places where laws against femicide are in place. Research shows that lack of implementation and enforcement of laws, as well as data gaps and gender and other forms of discrimination all contribute to impunity. This policy brief presents evidence and makes recommendations to address another factor in the persistence of femicide: media reporting. It makes the case for a role for the news media in challenging, rather than reproducing, harmful stereotypes and attitudes. It also suggests a gender-sensitive and rights-based approach to femicide reporting that leverages and adapts existing frameworks to address femicide in specific country contexts. 01 Policy Brief No. 1 Femicide: a social and political phenomenon Femicidei refers to the gender-related killing of women The rise of femicide during which often culminates in socially and politically tolerated murder. It constitutes the most extreme end Covid-19 of a continuum of gender-based violence (GBV), violating women’s right to life and freedom from violence, torture, and gender-based discrimination. Data on GBV during the Covid-19 pandemic from Femicide is a global phenomenon that takes place in around the globe show an intensification of sexual both private and public spheres, though more than and physical violence, and especially domestic half of the 87,000 women intentionally killed in 2017 violence, leading to calls to address a “shadow xi were killed by intimate partners or other family pandemic.” Several countries in Latin America membersii. -

No. 27 November 15, 2018

No. 27 November 15, 2018 Femicide, the most extreme expression of violence against women At least 2,795 women were victims of femicide in 23 Latin American and Caribbean countries in 2017, according to data provided by national public agencies to ECLAC’s Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. In El Salvador this phenomenon is particularly acute, finding no other parallel in any country in the region, with a rate of 10.2 femicides per 100,000 women in 2017. This is followed by Honduras, which in 2016 registered 5.8 femicides per 100,000 women. In Guatemala, the Dominican Republic and Bolivia (Plur. State of) high rates were also observed for 2017, which are equal to or greater than 2 cases per 100,000 women. Venezuela, Panama and Peru are the only countries in the region with rates below 1.0. Figure 1 Latin America (16 countries): Femicides, last year with available information (Absolute numbers and rates per 100,000 women) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean [online] http://oig.cepal.org/en, on the basis of official sources. * Chile and Colombia record information only on cases of intimate femicide, committed by intimate or former intimate partner. The data shows that femicides (homicides of women perpetrated for gender-based reasons) usually correspond to a majority of the total intentional homicides of women. In most countries of the region with available data, femicides are committed by someone with whom the victim had or had had an intimate relationship. -

Pregnancy, Femicide, and the Indispensability of Legalizing Abortion: a Comparison Between Argentina and Ireland

Emory International Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 2020 Pregnancy, Femicide, and the Indispensability of Legalizing Abortion: A Comparison Between Argentina and Ireland Agustina M. Buedo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Agustina M. Buedo, Pregnancy, Femicide, and the Indispensability of Legalizing Abortion: A Comparison Between Argentina and Ireland, 34 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 825 (2020). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol34/iss3/3 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUEDOPROOFS_5.11.20 5/11/2020 1:12 PM PREGNANCY, FEMICIDE, AND THE INDISPENSABILITY OF LEGALIZING ABORTION: A COMPARISON BETWEEN ARGENTINA AND IRELAND INTRODUCTION Although Argentina has relatively high levels of education, strong civil- society groups, and a long history of feminist activism, the country remains stagnant on change regarding women’s rights, specifically, reproductive rights.1 Among the long-standing human rights problems in Argentina is the “endemic violence against women, restrictions on abortion, [and] difficulty accessing reproductive services.”2 Argentine law considers abortion a crime with the exception of two narrowly defined circumstances: (a) if the abortion is carried out with the purpose of averting risk to the mother’s life or health when that risk cannot be averted by any other measure; or (b) in the case of the rape of a mentally disabled woman.3 This kind of law perpetuates both the cultural and institutional restraints surrounding abortion that are “paradigmatic of how women’s bodies are socially regulated in Argentina.”4 Restricting abortion has severe implications—more violence against women. -

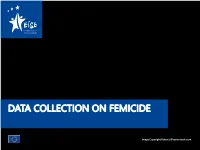

Data Collection on Femicide

DATA COLLECTION ON FEMICIDE Image Copyright:fizkes's/Shutterstock.com CHALLENGES FOR DATA COLLECTION • No international defintion of “femicide” • Terminology of femicide not adapted to statistical purposes • Lack of disaggregated approaches to data collection • Technical obstacles in data collection at national level LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT Victims’ Istanbul Rights Convention Directive Report of CEDAW GR UNODC 35 (49) (2019) & Road Map DEFINITIONS BY ACADEMIA The killing of females by males because they are females (Russell, D. 1976) The murder of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure or a sense of ownership over women (Caputi and Russell 1990) The misogynistic killings of women by men (Radford & Russell, 1992) DEFINITIONS OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS Vienna WHO MESECVI ICCS Declaration (UN) Femicide is the The The violent killing of women An unlawful death killing of women and intentional because because of gender, inflicted upon a girls because of their murder of whether it occurs within the person with the gender women family, domestic unit or any intent to cause because they other interpersonal death or serious are women relationship, within the injury community, by any individual or when committed or tolerated by the state or its agents, either by act or omission COMPONENTS Intentional Killing 24 Death related to unsafe abortion 14 FGM-related death 9 Killing of a partner or espouse 7 Gender-based act and/or killing of a woman 6 Death of women resultinf of IPV 5 COMPONENTS OF FEMICIDE OF COMPONENTS Dowry-related deaths Females foeticide Honour-based Killings 0 10 20 30 NUMBER OF MEMBER STATES COMPONENTS KEY COMPONENTS Gender Gender inequalities motivation EIGE’s DEFINITION AND INDICATOR The killing of a woman by an intimate partner and the death of a woman as a result of a practice that is harmful to women. -

Inter-American Model

Inter-American Model Law on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of the Gender-Related Killing of Women and Girls(Femicide/Feminicide) The Organization of American States (OAS) brings together the nations of the Western hemisphere to promote democracy, strengthen human rights, foster peace, security and cooperation and advance common interests. The origins of the Organization date back to 1890 when nations of the region formed the Pan American Union to forge closer hemispheric relations. This union later evolved into the OAS and in 1948, 21 nations signed its governing charter. Since then, the OAS has expanded to include the nations of the English-speaking Caribbean and Canada, and today all of the independent nations of North, Central and South America and the Caribbean make up its 35 member states. The Follow-up Mechanism to the Belém do Pará Convention(MESECVI) is an independent, consensus- based peer evaluation system that looks at the progress made by States Party to the Convention in fulfilling its objectives. MESECVI is financed by voluntary contributions from the States Party to the Convention and other donors, and the Inter-American Commission of Women (CIM) of the OAS acts as its Secretariat. Inter-American Model Law on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of the Gender-Related Killing of Women and Girls (Femicide/Feminicide) Copyright ©2018 All rights reserved OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission of Women. Follow-up Mechanism to the Belém do Pará Convention (MESECVI). Ley modelo interamericana -

Femicide and Feminicide

Guatemala Human Rights Commission / USA Fact Sheet Femicide and Feminicide Femicide Femicide is not simply the murder of females but rather the killing of females by males because they are female. It is a form of terrorism that functions to define gender lines, enact and bolster male dominance, and to render women chronically and profoundly unsafe. Femicide occurs throughout the world – China, India, Middle East, Africa, Latin America Approximately 40% of violent deaths of women in Guatemala take place in Guatemala City. Statistics on femicide in Guatemala according to the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office: Year Number of Women Killed Femicide in Guatemala 2001 317 2002 317 800 700 2003 383 600 500 2004 497 400 2005 517 300 200 2006 603 100 WomenKilled 0 2007 590 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2008 722 Year Total: 3,946 Famous Case: Claudina Isabel Velásquez Paiz Claudina Isabel Velásquez went to a party in Guatemala City, where she lived with her family. The next day, her body was found abandoned on a city street. Because of her father’s quest for justice, her story is known internationally (Killer’s Paradise, BBC, 2006). To date, her case remains unresolved because of the authorities’: Failure to promptly open an investigation Failure to preserve the crime scene Failure to collect evidence from the crime scene Failure to perform adequate forensic tests and analysis Failure to interview witnesses Frequent rotation of investigators Re-victimization and harassment of victim’s family Claudina Isabel Velásquez Paiz Feminicide Feminicide is a political term. It encompasses more than femicide because it holds responsible not only the male perpetrators but also the state and judicial structures that normalize misogyny. -

Pregnancy and Intimate Partner Violence: Risk Factors, Severity, and Health Effects

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2011 Pregnancy and Intimate Partner Violence: Risk Factors, Severity, and Health Effects Douglas A. Brownridge University of Manitoba, [email protected] Tamara L. Tallieu University of Manitoba Kimberly A. Tyler University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Agnes Tiwari University of Hong Kong Ko Ling Chan University of Hong Kong See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Sociology Commons Brownridge, Douglas A.; Tallieu, Tamara L.; Tyler, Kimberly A.; Tiwari, Agnes; Chan, Ko Ling; and Santos, Susy C., "Pregnancy and Intimate Partner Violence: Risk Factors, Severity, and Health Effects" (2011). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 154. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/154 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Douglas A. Brownridge, Tamara L. Tallieu, Kimberly A. Tyler, Agnes Tiwari, Ko Ling Chan, and Susy C. Santos This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ sociologyfacpub/154 Published in Violence Against Women 17:7 (2011), pp. 858–881; doi: 10.1177/1077801211412547 Copyright © 2011 Douglas A. Brownridge, Tamara L. Taillieu, Kimberly A. Tyler, Agnes Tiwari, Ko Ling Chan, and Susy C. Santos. Published by Sage Publications. Used by permission. http://vaw.sagepub.com Pregnancy and Intimate Partner Violence: Risk Factors, Severity, and Health Effects Douglas A. -

Issue Brief: Sexual Violence Against Women in Canada

Issue Brief: Sexual Violence Against Women in Canada By: Cecilia Benoit Leah Shumka Rachel Phillips Mary Clare Kennedy Lynne Belle-Isle This Issue Brief was commissioned by the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Senior Officials for the Status of Women The ideas and opinions in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Governments. December 2015 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 Background/Context ........................................................................................................... 4 What is “Sexual Violence”? ........................................................................................... 4 Challenges in Accurately Assessing the Scope of the Problem ...................................... 4 Theoretical Approach to Sexual Violence ...................................................................... 6 Summary of What We Know About Sexual Violence in Canada .................................... 12 National and Provincial Prevalence .............................................................................. 12 Sexual Violence and Vulnerable Populations of Women ............................................. 17 Sexual Violence and Online Environments .................................................................. 24 Consequences and Impacts of Experiencing Sexual Violence ......................................... 26 -

"This Murder Done": Misogyny, Femicide, and Modernity in 19Th- Century Appalachian Murder Ballads

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2011 "This Murder Done": Misogyny, Femicide, and Modernity in 19th- Century Appalachian Murder Ballads Christina Ruth Hastie [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Musicology Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hastie, Christina Ruth, ""This Murder Done": Misogyny, Femicide, and Modernity in 19th-Century Appalachian Murder Ballads. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1045 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Christina Ruth Hastie entitled ""This Murder Done": Misogyny, Femicide, and Modernity in 19th-Century Appalachian Murder Ballads." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major